What you should know about deep-sea mining

Photo: Cristian Palmer en Unsplash.Deep-sea mining consists of the exploitation of mineral deposits located deeper than 200 meters in the ocean.

Although interest in the technique dates back to 1960, initial ideas were never implemented due to factors such as low metal prices, relatively easy access to raw materials in the countries of the Global South, multiple technical difficulties, and legal uncertainty.

On the ocean floor, there are three types of resources of great economic interest: polymetallic nodules, ferromagnesian crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides generated by hydrothermal vents.

Currently, interest in these resources has regained strength due to geopolitical changes and greater demand from the non-conventional renewable energy sector. To date, 30 mining exploration contracts have been confirmed in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans involving 21 contractors from around the world among companies, government authorities, and science and technology institutes.

Unfortunately, we know very little about the ecosystems on the ocean floor and the real impacts of this type of mining. Some scientists believe that the recovery of the habitat would take decades to centuries and that, in some cases, the damage could be irreversible since certain environments are unique.

Socio-ecological impacts

Although ocean mining could stimulate the economy, the social impacts it entails must be emphasized, especially for the most vulnerable local communities, which depend on natural resources for their livelihoods.

Ocean mining has been associated with dilemmas such as foreign interference, cultural disruption, unequal distribution of wealth, loss of access to natural hunting grounds, and alterations in the distribution and migration of species, which would generate variations in the quantity and quality of fishing.

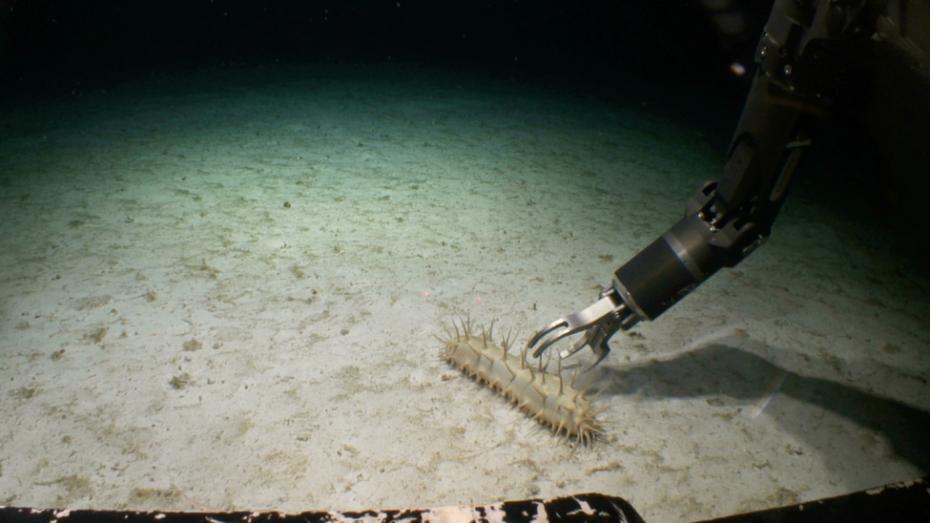

Ecological impacts include, among others: an increase of particulate matter in the water, greater mortality of organisms, habitat destruction, the risk of encountering unknown bacteria and viruses in the oceans, the arrival of invasive species through extraction equipment, and the risk of accidental spills caused by the inputs used.

The environmental management of this activity is also a concern. The agency in charge of regulating ocean mining is the International Seabed Authority (ISA), founded in 1994 by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

ISA has jurisdiction over the seabed and subsoil in international waters. It is currently developing a proposal for regulations for ocean mining, which has been faced with multiple challenges.

The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition—an alliance of more than 80 organizations that has been operating since 2004 with the objective of protecting the deep sea—questioned whether the proposal establishes that the form of environmental monitoring should depend on ISA or on the contractors. As early as 2018, the coalition stated that independent scientific review and assessment is key to all environmental documents, especially Environmental Impact Assessments and Environmental Monitoring and Management Plans.

It is pertinent to mention that, in addition to regulating mining in international waters, ISA is responsible for ensuring the ecological protection of the oceans from the potential harmful effects of activities developed or related to the seabed.

The fact that those promoting the projects may carry out environmental monitoring implies the risk of environmental problems due to conflicts of interest.

Looking ahead

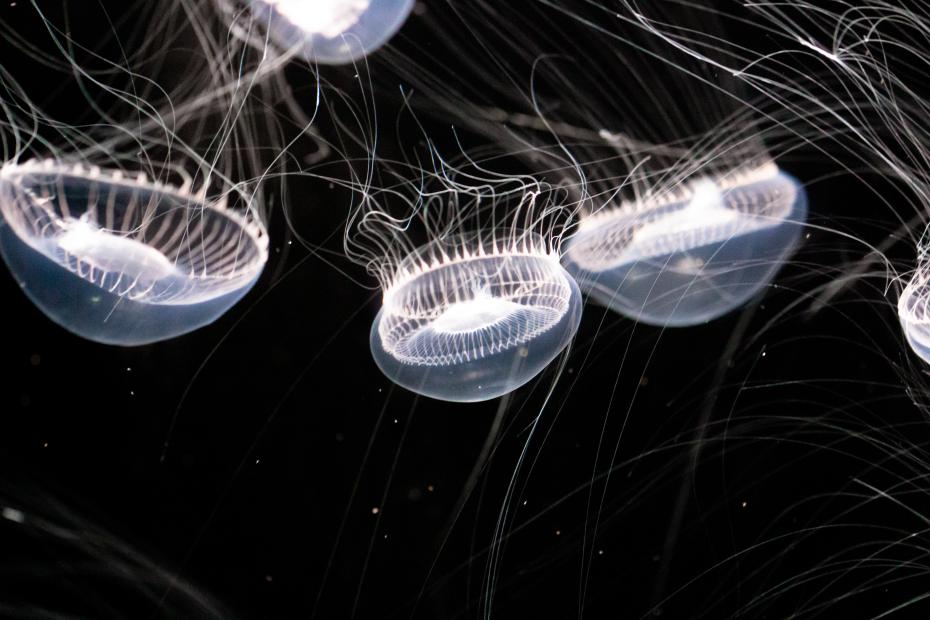

The ocean floor is the largest living area on our planet. There, ecosystems of splendid beauty exist, of which we know practically nothing, and which could suffer irreversible damage from deep-sea mining projects, scientists and conservationists have warned.

Healthy oceans play an integral role in global climate regulation and are essential to ensuring food security and livelihoods for millions of people around the world.

In addition, significant ignorance about how the deep ocean works make any attempt at Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and future projections difficult. In fact, on almost every new dive, new species are discovered. And much remains to be learned about the relationship between the ocean floor and the climate crisis, water acidification, and pressures from anthropogenic (human-induced) activities.

Without adequate knowledge of species, ecosystems, ecological processes, and their connections, EIAs cannot be effective.

The concept of the common heritage of mankind should be central to any proposal. Besides, it would be prudent to adopt legal protection measures such as the Precautionary Principle, as well as engage in prior exploration and research activities.

With all this in mind, ISA has an immense responsibility before the planet and humanity.

For the sake of a sustainable future and the natural legacy of future generations, ISA must ensure adequate protection of the oceans.

Should deep-sea mining finally be permitted on the high seas, they must pay close attention to prevention and mitigation measures using a precautionary and adaptive approach, in collaboration with other international bodies.

Esteban Ibarguren

Esteban Ibarguren Rüting is an intern in the Freshwater and Marine Biodiversity and Coastal Protection programs. He works with AIDA from Uruguay. He holds a degree in Biological Sciences with an emphasis on Environmental Management and Remote Sensing from the University of the Republic in Montevideo.