By Florencia Ortúzar, AIDA attorney

On December 8th, one of the last pristine places on the planet, Patagonia, lost one of its greatest protectors, Douglas Tompkins. At 72 years old, the conservationist and multimillionaire lost his life in a kayaking accident.

Much has been said about the eccentric man who sold the companies that made him rich, and left it all behind to undertake an ambitious conservation project in Chile and Argentina. It was looked on with suspicion when he began frantically buying lands in the Southern Cone for the sole purpose of protecting them.

Tompkins thought that effective conservation should be “extensive, wild and connected.” So he decided to create large national parks that would be protected even in his absence.

To do so, he acquired large tracts of land and began returning them to their natural state, removing fences and recuperating ecosystems. Without fences, wildlife could move freely, a condition which is fundamental for their prosperity.

Barely more than a month after she was widowed, Kris Tompkins, Doug’s wife for 20 years, met with Chilean President Michelle Bachelet to offer the donation of more than 400 thousand hectares of land in Chilean Patagonia, including millions of dollars in infrastructure. With it, she sought to realize the last of the couple’s major projects in Chile: the creation of Patagonia Park, which together with other lands, donated or in process of being donated, would form a network of parks in Patagonia.

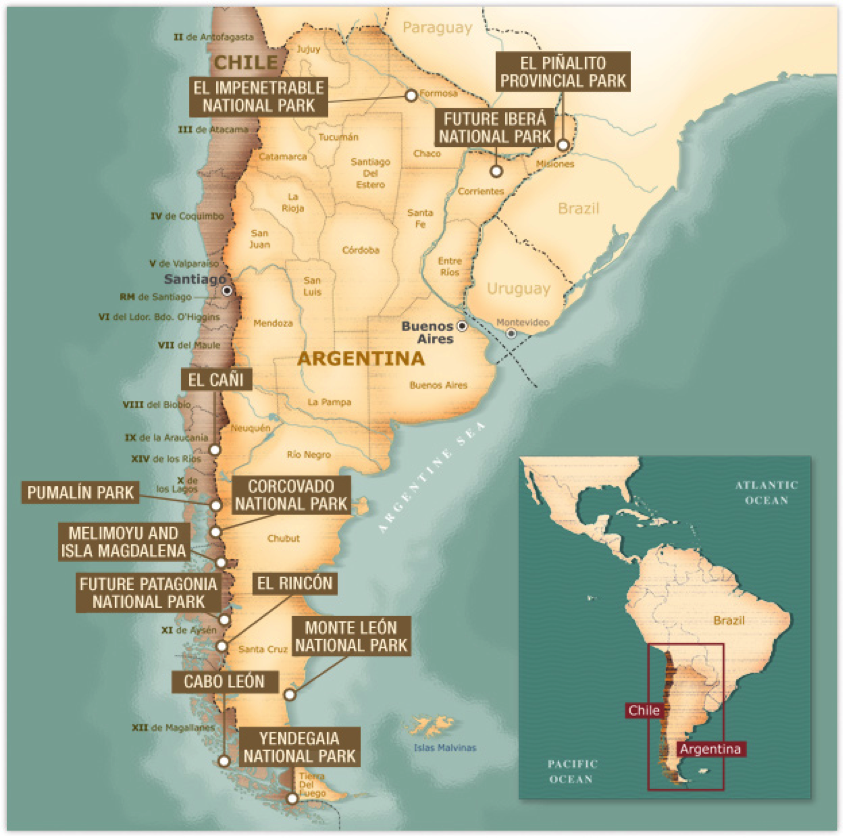

In Chile, the Tompkins had already donated land for the creation of Corcovado Park in Patagonia and Yendegaia Park in Tierra del Fuego. The land to create Pumalín Park, also in Patagonia, is in the process of being donated. All together, these land donations equal more than 500 thousand hectares of protected wilderness.

But the Tompkins’ gifts come with conditions: for each hectare they receive, governments must protect a certain number more. In exchange for the posthumous donation in Chile, for example, the government is required to create new national parks, expand existing parks and reclassify four natural reserves. Negotiations are expected to conclude in 2018.

If the Tompkins’ succeed, the agreement will create the most important network of national parks in the country.

Tompkins also donated vast stretches of land in Argentina. In the Entre Ríos Province, he started a soil recuperation project, using highly diversified organic crops to overcome the damage of industrial monoculture.

The Argentine Patagonia also received protection, through land donations of 66 thousand hectares to Monte Leon National Park and 15 thousand hectares to Perito Moreno National Park.

Tompkins’ last project in Argentina was completed last December when the Argentine government met with Kris Tompkins to accept the donation of 150 thousand hectares of land in the Estuaries of Iberá, the second largest wetland on the planet. This area, when added to the 50 thousand hectares previously donated and the 500 thousand that already form Iberá Park, will create one of the largest reserves in the country.

In addition to contributing to the creation of national parks, Tompkins supported the activism of conservation groups in Patagonia. One of the initiatives he sponsored was the campaign Patagonia sin Represas, which managed to stop the HidroAysén project in its tracks. HydroAysén had aimed to construct five mega-dams on the Baker and Pascua rivers, two of the largest free-flowing rivers in Chile, located in the heart of Patagonia. During Doug’s burial the mantra “Patagonia sin Represas” is said to have been shouted by mourners when the last handful of dirt was thrown upon his grave.

At the end of the 1900s, when Tompkins’ land purchasing in Argentina and Chile was at its peak, he was accused of buying the land cheaply and displacing its inhabitants, leaving them without work. Later, the accusations became more sophisticated: they accused him of buying land to create a new Zionist state, of being a CIA spy, and of trying to seize enormous reserves of fresh water to export to places experiencing drought.

Many looked upon his work with suspicion. Maybe they found it difficult to believe that someone would invest millions of dollars with the sole objective of preserving the perfect natural harmony that surrounds us. Any accusation was easier than giving credit to his true

intention: buying land to prevent it from being exploited, and then giving it back to the government, not for money, but for a commitment of protection.

Whatever his detractors may say, here in reality, Douglas Tompkins left an enormous legacy to all of mankind. He has conserved more land than any other person in the history of Chile and Argentina. His work has translated into massive patches of green on the maps of Patagonia.

For those pristine and wild places, we are eternally grateful.

CONGRATULATIONS DOUG, and THANK YOU!