Still Waiting for Justice in La Oroya

Part 1 of a 2-Part Series on the Human Rights Situation in La Oroya, Peru.

By María José Veramendi Villa

Juana[1] is tired. She and her neighbors have been waiting eight years for a ruling; eight years for a decision that could better their lives, clean their air, attend to their sick children and families.

What began as a courageous and hopeful quest for justice has become a discouraging waiting game. Since 2007, a group of residents in La Oroya, Peru, has acted as petitioner in a case before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Community of La Oroya v. Peru.

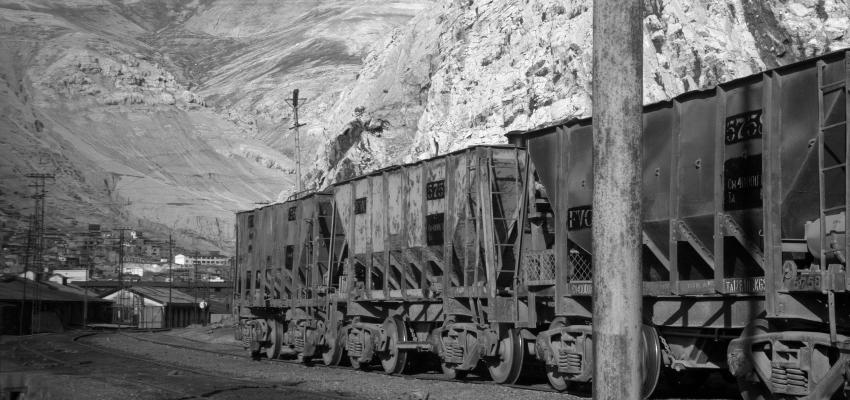

For nearly a century, their city has been contaminated by the operation of a metallurgical complex (smelter) within its borders. The smelter has blackened the air, poisoned their bodies, and released toxic chemicals into the land and water.

La Oroya was once identified as one of the most polluted cities in the world. The severe contamination has, and continues to have, grave impacts on the health of the city’s residents.

Realities of La Oroya

When AIDA’s co-executive director Anna Cederstav first arrived in La Oroya in 1997, women were walking around with scarves covering their faces, a vain attempt to ease the pain of breathing. Juana explained that she had felt the steady burning in her eyes and throat—the effects of contamination—since she could remember, but didn’t pay it any mind.

Like most of the population, she thought it was normal. She didn’t really know what clean air was because she’d never experienced it.

AIDA has worked for nearly two decades with the community of La Oroya. In 2002, we published the report La Oroya Cannot Wait with the Peruvian Society for Environmental Law. That report began to reveal to the community the severity of the pollution and health risks they were facing on a daily basis. The community realized they had to do something.

Juana said it was in 2003, more than 80 years after the smelter began operating, that she became aware of the contamination. Through work with her parish, she was able to access information and learn about what was happening in her city.

From there, she connected the dots—the respiratory problems in her family were, in fact, a result of her city’s extreme contamination.

The quest for justice

Residents submitted their case before the Inter-American Commission after their attempts at justice within Peru produced no remedy. A 2006 ruling by Peru’s Constitutional Tribunal against the State ordered it to adopt measures to protect the health of the community, but the State took no such action.

In 2007, the Commission urged the Peruvian state to carry out precautionary measures—a specialized diagnosis of 65 residents and treatment for those who showed irreversible damage to their lives or personal integrity.

Juana said receiving news of the precautionary measures was a happy moment because “we knew that we were winning something. At the beginning, everything went well and we believed that everything would be fixed, (but) with the passing of months—years—there were no answers.”

Then, in 2009, the Commission issued a report admitting AIDA’s petition, declaring that the State’s omissions in the face of pollution could, if proven, represent human rights violations. But still, nearly a decade after the petition was first filed, the victims await a decision, the precautionary measures have yet to be enforced, and the State’s responsibility for the acts have yet to be established.

“It’s taking a really long time, and not all of us have the patience or desire to keep waiting,” Juana said.

Time affects the victims, wearing them out until they begin to waver and give up fighting for their right to justice. They become even more vulnerable as they face a city hostile to anyone who fights for their rights to life and health, a state that denies its responsibility and looks for any excuse to avoid assuming responsibility, and a company that wants to polish its reputation and use its economic power to manipulate the government. Where is the law in these cases? Where is justice?

Juana explained that leaving La Oroya would be impossible for her family, because there they have work. She remains committed to achieving change with the lawsuit. But that’s not the case for everyone.

La Oroya contains thousands of stories of families whose lives were radically changed due to the city’s contamination and the subsequent damages to their health and lives.

There are those who had to abandon their homes because they did not see a future in the city, and those who have been unable to leave La Oroya because their entire lives and family are there. Then there are those who have suffered painful attacks and insults from their own neighbors in a community worried about losing jobs, but who march forward with the conviction that, one day, change will come and La Oroya will be a better and fairer place for them, their children, and their grandchildren.

I trust and hope that the law will deliver justice to salvage those years of waiting.

[1] The name has been changed to protect the client.

This blog is based on a longer article Maria José wrote on the case entitled La Oroya: A Painful Wait for Justice. It was published as Chapter 8 of DeJusticia’s book, Human Rights in Minefields: Extractive Economies, Environmental Conflicts and Social Justice in the Global South. Read the full account here.

María José Veramendi Villa

María José Veramendi Villa was AIDA senior attorney for the Human Rights and Environment Program. She is a Peruvian lawyer with degrees from the Universidad de Los Andes in Bogota, Colombia and the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. She has a diploma in Women and Human Rights: Theory and Practice from the Universidad de Chile and an LLM (Master of Laws) in International Legal Studies with a specialization in human rights from the American University Washington College of Law. Previously, she was a researcher in the Human Rights Program at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City, and worked as a human rights lawyer for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and as a lawyer at the Legal Defense Institute in Peru. She has worked as a teacher and lecturer of various courses and seminars, and has been published in an array of publications on the subject.