Stopping Fracking: Together We’re Stronger!

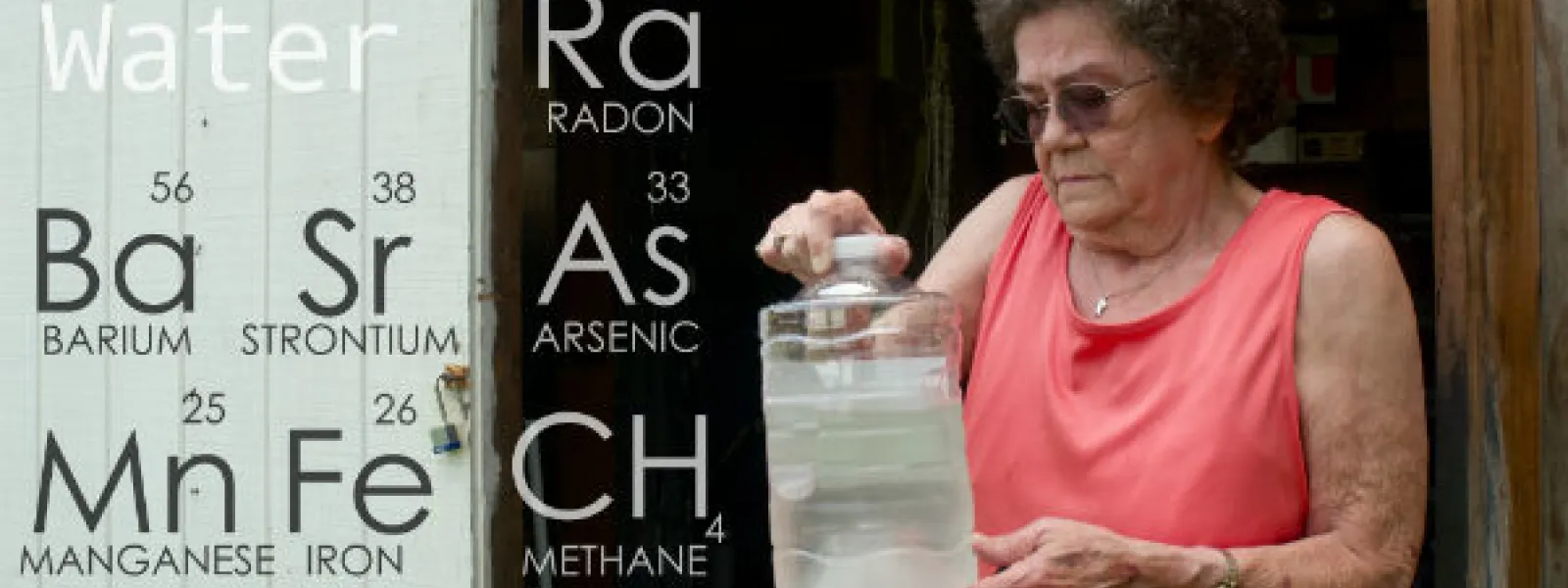

Credit: Public Herald/Creative Commons.It’s an increasingly recognized reality: the world cannot burn its reserves of fossil fuels and expect the planet to be habitable.

But energy companies continue extracting fossil fuels in pursuit of near-term profit, rather than adapting their business models for the sake of long-term sustainability. Already, much of the world’s reserves of easily extracted, high-quality fossil fuels have been exhausted.

New horizontal drilling technology, combined with hydraulic fracturing (fracking), has made exploitation of hard-to-reach ("unconventional") oil and gas deposits possible. For a variety of reasons, fracking poses very high risks to public health and the environment.

AIDA has begun working with civil society organizations and institutions to generate information, stimulate debate, and join forces to prevent the negative impacts of fracking in Latin America.

The Risks of Fracking

Fracking for unconventional deposits involves drilling into the ground vertically, to a depth below aquifers, and then horizontally through layers of shale rock. Then fracking fluid (a high-volume mixture of water, sand, and undisclosed chemicals) is injected at very high pressure to fracture the shale, thus releasing the oil and gas trapped inside. After fracking fluid surfaces, energy companies typically dump it into unlined ponds. The chemical soup—now also contaminated with heavy metals and even radioactive elements—seeps into aquifers and overflows into streams.

The severe and irreversible damage associated with fracking includes:

The severe and irreversible damage associated with fracking includes:

- Exhaustion of freshwater supplies.

- Contamination of ground and surface waters.

- Air pollution from drill and pump rigs.

- Harms to the health of people (low birth weight, birth defects, increases in congenital heart defects, deformities, allergies, cancer, and respiratory disease) and other living things.

- Unregulated emissions of methane, which traps 25 times more heat than carbon dioxide.

- Earthquakes.

- Effects on subsistence activities, such as agriculture.

For and Against Fracking

Given these risks, France, Bulgaria, Ireland, and New York State have turned their backs on fracking, banning it or declaring a moratorium in their territories.

In Latin America, however, many countries are opening their doors to fracking. Governments are doing so with little or no understanding of its impacts, and in the absence of an adequate process to inform, consult, or invite the participation of affected communities:

- Mexico promoted fracking through a landmark energy reform law in 2013. As of 2015, 20 wells have been drilled using this technique.

- Argentina has the largest number of fracking operations in the region, and the largest reserves of shale gas in America. As of 2014, there were more than 500 fracking wells in Neuquén, Chubut, and Rio Negro[6], including wells in the Auca Mahuida reserve and in Mapuche indigenous territories.

- In Chile, the state-owned oil company ENAP started fracking on the island of Tierra del Fuego in 2013. More drilling is planned in the coming years.

- Colombia and Brazil have opened public bidding and signed contracts with oil companies for exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbons through fracking.

- Bolivia's state-owned oil company signed an agreement in 2013 with its counterpart from Argentina to study the potential of fracking in Bolivia.

Better together

In October 2014, with the help of AIDA, the Regional Alliance on Fracking was formed to raise awareness, generate public debate, and prevent risks associated with the technique. The alliance seeks to ensure that the rights to life, public health, and a healthy environment are respected in Latin America.

The idea for the alliance came from previous regional coordination initiatives promoted by Observatorio Petrolero Sur and the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

The alliance currently consists of 33 civil society organizations and academic institutions from seven countries in the region. They are working together to:

- Identify fracking operations in the region, their impacts and affected communities, and promote civil society strategies to stop them.

- Organize workshops and virtual seminars on the impacts of fracking.

- Develop international advocacy strategies to stop fracking in the region.

- Conduct a regional outreach campaign on the issue.

The alliance is strengthened by the expertise of its members, its regional scope, and the institutional support provided by organizations in each country. Given its collaborative nature, it is always open to the participation of new institutions and individuals interested in the subject.

Major achievements

Many civil society organizations, indigenous peoples, and institutions in the region have been working to stop fracking. They have developed strategies to generate information, raise awareness, promote public debate, and influence decision makers. Their achievements encourage us to improve coordination for greater impact throughout Latin America.

Already, their efforts have resulted in:

- More than 30 municipal orders declaring a ban or moratorium on fracking in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Many have been based on the precautionary principle, as well as on concerns about surface and ground waters and public health.

- Judgments suspending contracts for fracking in Brazilian oil basins in Sao Paulo, Piauí, Bahia, and Paraná. Judges have also ordered Brazil’s National Petroleum Agency not to open further bidding until the environmental risks and impacts of fracking are sufficiently understood.

- Publications on the impacts of fracking, community awareness campaigns, and a bill – supported by more than 60 national deputies and nearly 20,000 people – to ban fracking in Mexico.

- Greater public awareness of fracking, and public debate, in Colombia and Bolivia.

Through regional collaboration, AIDA will continue to make progress on preventing the impacts of fracking in our communities, and promote an energy future that is both renewable and humane.

Ariel Pérez Castellón

Ariel Pérez Castellón is Bolivian environmental lawyer and was part of the AIDA’s Freshwater Preservation Program. He received a law degree from the Universidad Católica de Bolivia and specialized in metropolitan environmental management and oil & natural gas law at the University of Buenos Aires. He is a professor of environmental and hydrocarbons law. Over the past 15 years, he has worked at national and international NGOs and as an independent researcher on issues related to extractive industries, the rights of indigenous peoples, and good governance in public policy in Bolivia and Argentina and on regional projects in Andean countries.