There is a blot in the middle of the ocean…

By Florencia Ortúzar, legal advisor, AIDA

The first time I heard about the mysterious “rubbish island” I was shocked. How could a huge floating mass as big as a country go unnoticed in the ocean without being on everyone’s lips? Incredibly, many people haven’t even heard of this Pacific Trash Vortex that grows larger every day, making it the world’s largest rubbish dump.

A soup of what?

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, as it’s officially known, is one of the five floating rubbish dumps polluting our world’s oceans. It was the first to be discovered and is the biggest. It’s located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean between the U.S. states of Hawaii and California, about 1,000 kilometers off the coast of Hawaii. The size of the rubbish heap is difficult to determine. Estimates range from about 15,000 square kilometers (equivalent to the surface area of Antarctica or 8.1% of the Pacific Ocean) to 700,000 square kilometers (almost the surface area of Chile).

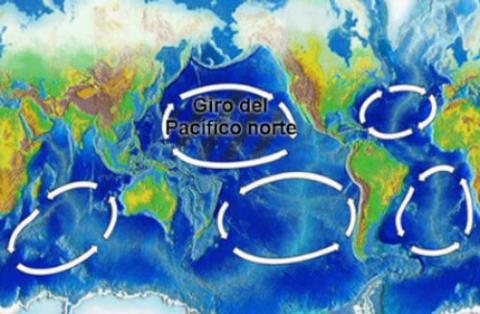

Let me explain a little more about this sad and unusual phenomenon. The island of rubbish is not a solid island as such, nor a floating sheet of trash. Rather, it’s a soup of plastic particles floating in a gyre. Ocean currents collect thousands of tons of floating garbage and round them up in a giant vortex. The slowly rotating mass prevents the rubbish from dispersing.

This soup has everything: abandoned fishing nets, plastic bottles, caps, toothbrushes, shoes and much more. But more than anything, the vortex consists of small particles of plastic created when the waves and sun break down larger pieces. This gigantic mass remains below the surface of the water in a column estimated to extend 30 meters deep.

Paradoxically, despite its huge size, the rubbish dump is not easy to visualize as a whole and has not been captured in satellite images because of its location under the water. Worse, it is located in international waters, so no nation is responsible for the waste. After concerned scientists and environmentalists, the only people left to help clean up the mess are passengers on special cruise ships who visit the vortex to help remove some of the rubbish. In all, it’s a gigantic mess going unnoticed, growing slowly but surely in a no man’s land devoid of a god or the rule of law.

A chance discovery

In 1988, experts from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted the existence of the garbage patch in the North Pacific Ocean by analyzing local marine currents. But it wasn’t until a decade later when oceanographer Charles Moore officially discovered the trash heap, which was dubbed the "Eastern Garbage Patch." In July 1997, Captain Moore was sailing through the North Pacific Gyre when he came across miles and miles of synthetic pieces of debris, and an immense mass of floating garbage. It took the American one week to cross the accumulation of waste.

In 1994, Moore established the foundation Algalita Marine Research to focus on the protection and regeneration of kelp forests and wetlands along the coast of California. But after his floating garbage island discovery, Moore dramatically changed the course of his foundation and dedicated it to raising awareness and promoting education about the garbage patch. (See Moore’s TED talk).

Expeditions to the forgotten island

Since its discovery, there have been various scientific expeditions to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and other floating garbage islands like it. Unfortunately, these trips have not managed to generate a significant amount of public awareness or impact outside environmental circles. Nobody seems to be willing to take responsibility or action.

The most recent expedition in May was organized by the Society of French Explorers (in French) on a schooner called L’Elan, assisted by Captain Moore on board. The results of the mission have not yet been published. Hopefully now with the ability of social networks to disseminate information widely, the issue will generate more interest and make people aware of the huge amount of plastic we consume.

What can we do?

As mentioned above, the garbage island mainly consists of billions of plastic pieces too small to be seen. This makes it difficult for the debris to be removed from the ocean. You would have to put a very fine net across the surface of the water, which would disturb the ecosystem and essential marine fauna such as plankton, a key food source for ocean animals. What is more, accessing the polluted area would require a considerable amount of resources including manpower and expensive materials to undertake the difficult work out in the open seas. The task becomes even more unlikely where you consider that the garbage island is located in international waters where no country is sovereign (the tragedy of the commons).

For now and until we come up with new technology that lets us travel back in time to prevent this disaster, the best and most sensible thing to do is to stop producing so much garbage, and especially to limit our consumption of disposable plastic. It is also important to help raise awareness of the problem so more people understand the effects of their consumerism, change their lifestyles and educate future generations who will be looking after the planet.

The island of trash consists of materials that at one time helped revolutionize the world. Today we are surrounded by plastic: we eat and drink from it. We use it every day. It is present in nearly all of our activities. Plastic is almost a miracle product. Cheap, effective and virtually indestructible, it doesn’t break. It just disintegrates into smaller parts. The considerable durability of plastic means that almost all the plastic molecules ever created still remain somewhere on the planet. Now at least we have a better idea on where they end up: on rubbish island.

Florencia Ortúzar Greene

Florencia is the Director of AIDA's Climate Program, and Coordinator of the Climate Finance Area, working from Santiago, Chile. She obtained her Law degree from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and also completed an MSc in Environmental Politics and Regulation at the London School of Economics (LSE) in England. She joined our team in 2012 and collaborates with Climate and Ecosystem programs. She enjoys spending time with her pets as well as cooking, camping and nature trekking.