Biodiversity and indigenous languages: one heritage to protect

When we lose words, we don’t know how to name what we see. And if what we see disappears, what do we do with the words we once used?

"Words that are not used, are forgotten," wrote young essayist Laura Sofía Rivero. "We say trees because we can't pinpoint what stands before us among all that vast category."

Why do we lose these words? There are complex political, historical, economic and educational reasons that have led to what linguist Yásnaya Aguilar of the Ayuujk people in Oaxaca, Mexico has called a "massive death" of languages.

Today, species and lifestyles that deserve unique words are disappearing and we are also losing the people who have long known those words. The loss of some is related to the loss of others.

The rate at which species and languages are disappearing has accelerated since the beginning of the 20th century. Although there is a whole scientific discussion to agree on a rate of annual biodiversity loss, as there are many variables that are left out, there exists great consensus that we are entering a sixth mass extinction.

The same could be said of languages. UNESCO estimates that a language becomes extinct every two weeks—implying that 3,000 languages, mostly indigenous, could be lost before the end of this century.

And this is where biodiversity and linguistic diversity meet. In the most biodiverse areas of the planet, 70 percent of existing languages are spoken: 4,800 of the 6,900 spoken worldwide. In Latin America, 80 percent of natural areas encompass or converge with territories inhabited by indigenous peoples.

One fact, as surprising as it is alarming, is that 3,202 languages—nearly half of all existing languages—are located in just 35 biodiversity hotspots, defined as places that require our immediate attention and action. A biodiversity hotspot is a region that is home to at least 1,500 species and has lost at least 70 percent of its habitat.

Habitat destruction unleashes a chain of impacts ranging from damage to ecological cycles to drastic changes in the lives of those who inhabit these areas. And to do anything, we need to understand the interconnectedness of all the elements that make up biocultural richness.

WHAT ARE WE LOSING WITH LANGUAGES?

Words are born because there are fruits, plants, and animals that need to be named. There is a wealth of sounds and rules, where abundance of life is the norm and there are different lifestyles and social organization. Yásnaya Aguilar** has an example for this: in Matlatzinca—spoken in central Mexico—there are four different "we's", in Mixe (Ayuujk) there are two and in Spanish, one.

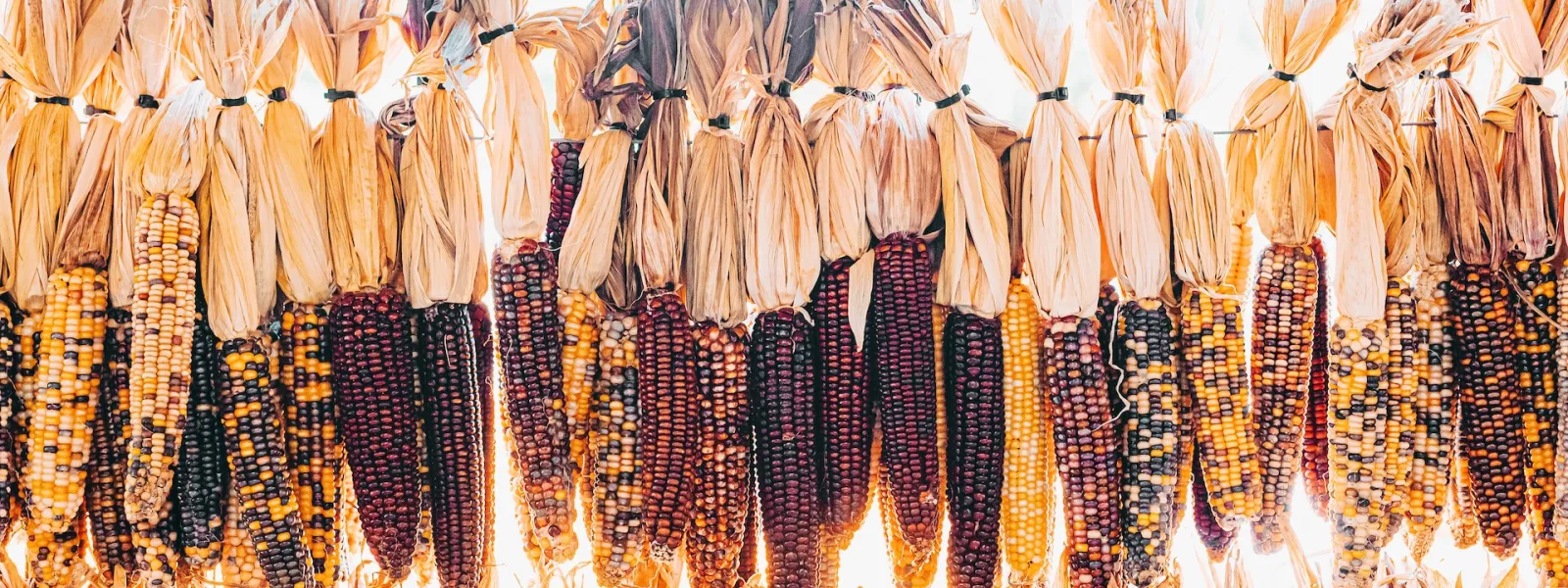

The biodiversity and richness of words is easy to understand when we talk about food, as happens with corn, the essential and basic grain in the Mesoamerican diet. To begin with, the history of the word mahis, whose origin is Taino, a now extinct language spoken in what is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic, is revealing. Each stage of corn cultivation and the ways of processing it have merited their own name in the cultures of the continent. For example, in the Xhon variant of Zapotec*— a language spoken in the mountains of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico— the plant is referred to as xhu'a, corn is called za (when it is cut and fresh) and, when it is already on the cob, yez. In Nahuatl, the most widely spoken native language in Mexico, there is a similar designation.

Food is an indicator of biodiversity loss. While there are more than 30 thousand species of plants that can be eaten, we only grow about 150 and almost all the calories consumed in the world come from just 30 species. Many languages have unique words for unique foods (species) that we have not even seen. Imagine what delicacies may be hidden in the 420 different languages spoken by the 522 indigenous peoples that inhabit Latin America.

We are losing an understanding of the systems that sustain life on the planet. The recognition of indigenous peoples as guardians of biodiversity and generators of empirical knowledge is very recent in Western science and culture, which is not to say that it has not been valid before. Several sections of the most recent IPCC report include the importance of this knowledge as a key element for preservation and adaptation in the midst of the environmental crises we face. The knowledge exists, but for centuries we have refused to engage in dialogue with it.

UNDERSTAND TO PROTECT

A few years ago, researchers proposed studying biological, linguistic and cultural diversity together because of the close relationship between them. UNESCO has since introduced the term "biocultural diversity." But to protect it, we must understand its complexity.

What benefits biodiversity in indigenous territories is absolutely necessary to face environmental crises. Data from the US Food and Agriculture Organization demonstrates that:

- Indigenous territories in Latin America store more carbon than all the forests of Indonesia or Congo, the countries with the most tropical forests after Brazil.

- Bolivia's Tacana and Leco Apolo indigenous territories are home to two-thirds of all their vertebrate species and 60 percent of their plant species.

- About 35 percent of Latin America's forests are found in areas inhabited by indigenous peoples.

- More than 80 percent of the area inhabited by indigenous peoples is covered by forests.

In general, indigenous territories report considerably lower rates of deforestation. Unfortunately, this is not the case for Brazil. The Amazon basin has been threatened for years by different extractivist activities, which were supported by the previous government. Particularly, where illegal mining has been installed, deforestation increased 129% since 2013. This situation does not stop there, it is reflected in the very serious humanitarian crisis that was recently declared for the Yanomami people or the situation of insecurity that was revealed with the murder in the middle of the Amazon of the peoples' rights activist Bruno Pereira and the journalist Dom Phillips.

Thus, to speak of protecting biodiversity and linguistic diversity becomes an exercise in speaking in defense of territory and environmental defenders; of access to justice, training and the creation of policies that truly integrate and contemplate the complexity of diverse life systems.

* Special thanks for the example in Xhon Zapotec to Ezequiel Miguel of the Proyecto Jaguar podcast that explores the identity elements of indigenous communities.

** To understand more about language preservation as an action for the defense of territory, I recommend reading Ää: manifiestos sobre la diversidad lingüística, by Yásnaya Aguilar, in Editorial Almadía.

Laura Yaniz Estrada

Laura Yaniz Estrada was part of AIDA's communications team. She holds a master's degree in Journalism and Public Policy from the Centro de Investigación y Docencias Económicas (CIDE). She holds a degree in Media and Journalism from the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey (ITESM) and a diploma in National Security from the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM). She is interested in new narratives and environmental security.