When the energy transition isn’t just: The case of Quintero and Puchuncaví in Chile

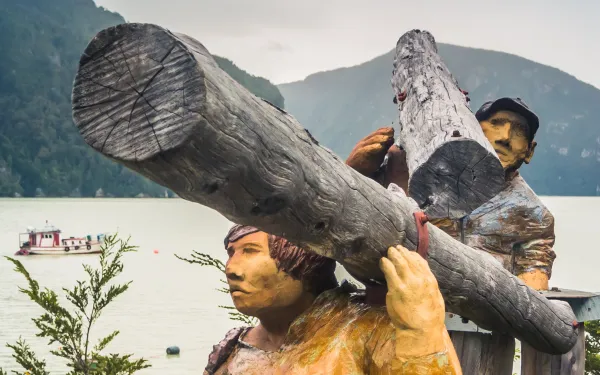

By Cristina Lux and Florencia Ortúzar * The energy transition in Chile will inevitably occur. In fact, it is already underway. The country doesn’t have large deposits of fossil fuels, but it does have abundant renewable energy resources. It only makes sense, then, that prior dependence on coal should naturally shift to the sun, wind and other renewable sources. Today, after decades of struggle by local communities, the closure of Chile’s original 28 coal-fired thermoelectric power plants is underway as part of the Decarbonization Plan promoted by the government in 2019. Eight have closed, six others have a future closure date, six more are in the process of establishing one, and eight do not yet have a closure plan. If the government and private actors deliver as promised, the thermoelectric plants as a whole should close before 2040, freeing Chile from the energy derived from burning coal. But the history of coal dependence will undoubtedly leave a deep mark. For many years, Chile obtained more than 50 percent of its energy from thermoelectric plants, all located in just five locations, known as "sacrifice zones." The people who live in those areas have long suffered at the expense of generating electricity for the rest of the country. The story of one of the most emblematic of Chile’s sacrifice zones, the bay of Quintero and Puchuncaví, demonstrates why the transition not only must occur, but why it has to be just. A beautiful seaside resort battered by pollution With a little more than 40 thousand inhabitants, the bay of Quintero and Puchuncaví is located two hours by road from the country's capital. The families there have historically lived from agriculture, artisanal fishing and tourism, ways of life that have been extinguished by the relentless advance of intensive industrial activity. Photo: Claudia Pool / @claudiapool_foto / www.claudiapool.com Today, the site is home to more than 30 different companies: a coal-fired thermoelectric complex, gas-fired thermoelectric plants, a copper refinery and a petroleum refinery, a regasification port, a cement plant, ports that receive coal and other fuels, as well as coal and ash storage centers, among others. Public information regarding the emissions of this mix of companies is deficient and the lack of regulations governing them is abysmal. In fact, only a few pollutants are regulated. The rest are not even measured, despite the fact that several are dangerous to human health. And so, paradoxically, the monitoring stations show normal levels as people are being intoxicated in the streets and schools. In the bay there are often mass poisonings of adults and youth, many of whom end up in the hospital. In these cases, schools are closed, but businesses are not, and the wind is monitored to activate protocols in case of poor ventilation. The blame is placed on the lack of wind instead of on those responsible for the pollution. It’s also common to see coal deposits on the beaches, which stain the sands. In 2022 alone, more than 100 episodes were recorded. It’s alarming how the situation affects local children, who are particularly vulnerable to pollution due to its effects on human development. The impact on women is also disproportionate, as they are the first to be forced to leave their jobs to care for sick family members since they bear the brunt of the care work. Things have not been done well in this beautiful coastal area. Today, new projects and the expansion of industrial operations continue to be approved. But the community is rising up, demanding a truce for this area. It is time to move towards ecological restoration in Quintero and Puchuncaví. Signs of hope Some recent events are giving hope that things could improve in the bay and that this area, which for years has been sacrificed in favor of the rest of the country, could once again show its beautiful beaches and wonderful fishing and agricultural resources to Chile and the world. Although the situation is not yet cause for celebration, some things seem to be moving in the right direction. One important step was the environmental damages lawsuit filed in 2016 by local communities against the government and all the companies in the industrial corridor. The process has been long, but a final judgment is expected soon. Meanwhile, in 2019, the Supreme Court resolved several appeals for protection for episodes of mass intoxications, giving reason to the communities and issuing a landmark ruling, perhaps the most important on environmental matters in Chile. The ruling orders the State to comply with 15 measures to identify the sources of contamination and repair the environmental situation in the area. Sadly, this ruling has not yet been properly implemented. Moving forward, the Supreme Court recently issued three rulings that refer to non-compliance with the 2019 ruling and provide tools to enforce compliance. Also, two of the four thermoelectric plants of the U.S.-owned AES Andes have closed operations in the bay. Two remain. Finally, in May, after 58 years of operation, the furnaces and boiler of the Ventanas Smelter were finally shut down. Thus, the icon of pollution in the area—a 158-meter chimney that consistently expelled pollutants—ceased to operate. The search for justice is far from over Despite the good signs, there is still no secure future for the people of Quintero and Puchuncaví. That’s why we must continue to demand justice and a transition that protects the most vulnerable people. Photo: Claudia Pool / @claudiapool_foto / www.claudiapool.com Although two of the four AES Andes thermoelectric plants operating in the bay have closed, the companies that owned them have been granted "strategic reserve status," whereby they are paid to remain available to operate again if required. On the other hand, although the copper smelter of the state-owned Corporación Nacional del Cobre closed, the refinery continues to operate in the area. There was a relocation plan for the workers, but no remediation plan for the communities that for almost six decades breathed the toxic waste of that industry. In addition, projects continue to be approved without the participation of the communities. This is the case of the Aconcagua desalination plant, which intends to desalinate water to transport it through subway pipes over 100 km to supply the Angloamerican mining company. Last but not least, decarbonization in Chile seems to bring an increase in the use of gas, which has been falsely labeled as a "transition fuel." It’s expected that gas activity in the area—which hosts one of the country's two LNG (liquefied natural gas) regasification ports—could intensify and, with it, so could its environmental impacts. Chile has the opportunity to set an example of just transition Chile, located at the end of the continent, has the opportunity to do things right. There are indications they’re moving in the right direction; the only thing missing is the political will to change course. The region of Quintero and Puchuncaví deserves the opportunity to shine again and to reach its full potential as a colorful coastal town and seaside resort with an identity rooted in agriculture, tourism and artisanal fishing. In this case, a truly just transition must include the closure of polluting companies that are making people sick. But it must also involve the participation of those people affected, putting the respect of their human rights at the forefront—a respect that was so diminished over the last six decades. The injustice that has weighed on the territory and its inhabitants must be recognized—establishing reparation mechanisms, ensuring non-repetition, and involving the people themselves in the environmental recovery of the area. Only in this way will the communities recover their capacity for agency—that power to decide and to be part of the decisions that affect them—which was taken away from them so many years ago. *Cristina Lux is an attorney with AIDA's Climate Program and Florencia Ortúzar is a senior attorney with AIDA.

Read more