The first time fracking was discussed before the Inter-American Commission

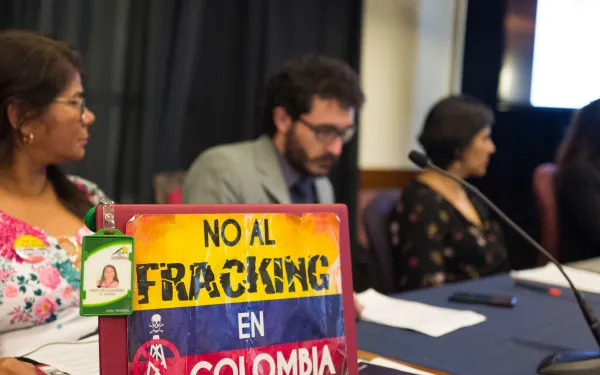

We heard the news at an exceptional moment. The Latin American Alliance on Fracking had organized a conference; activists, lawyers, NGOs, community organizers, and scientists from seven Latin American countries were meeting face to face in Colombia to work against hydraulic fracturing in the region. It was there we learned that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights had accepted our request for a hearing. We erupted in collective joy! Not only would we have a new audience, but also fracking would be discussed for the first time before the Commission. Immediately, we channeled our excitement into hard work. We had just 20 days to prepare a 20-minute case that would summarize every negative impact fracking has had in the Americas. We worked day and night to prepare our case for the October 3 hearing in Boulder, Colorado. It was so little time that Gabriel Cherqui, spokesperson for Mapuche communities affected by the Vaca Muerta mega-project in Neuquén, Argentina, couldn’t obtain a visa in time to travel to the United States. Years of work, converted into minutes Perhaps the most difficult aspect of preparing our case was summarizing thousands of documents and stories into such a short amount of time. It had taken years to systematize our specialized research on fracking in the region and to have our case before the Commission—requested with more than 120 supporting signatures—accepted. Another challenge was to demonstrate the solid connection between fracking and human rights violations, an argument we knew the Commission would be interested in addressing, given the scale and complexity of the problem. So we developed a strategy: Roberto Ochandio, a geographer and former petroleum engineer, presented the technical details necessary to understand how fracking works; AIDA attorney Liliana Ávila explained how the technique has violated the rights to a healthy environment, to life, health, and the informed consent of the affected communities; Alejandra Jiménez from the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking presented case studies from Mexico, where communities’ access to water had been compromised by fracking operations; Santiago Cané, from Argentina’s Environmental and Natural Resources Foundation (FARN), exposed the pollution, direct harms, lack of consultation with, and persecution of the communities of Neuquén; and Doris Estela Gutiérrez, president of the Corporation for the Defense of Water, Territory, and Ecosystems (CORDATEC), spoke about the promotion of public consultations in Colombia, as well as the criminalization of and threats to environmental defenders in the country. We emphasized that betting on hydrocarbons and promoting fracking undermines the fight against climate change, since fracking emits methane and other greenhouse gases that accelerate global warming. It was a challenge, to be sure. But we wanted to ensure everyone’s voice was heard. To listen, and learn: a window of hope Based on the response of the Commissioners, it was clear that our case had opened a window of hope. The multifaceted character of fracking—including aspects of development, pollution, climate change and human rights—had captured their interest. Not only was this the first time that fracking had been discussed before of the Commission, it’s worth noting that five speakers had summarized the concerns of more than 120 petitioners, all of whom shared one common cause. What came next was a dialogue in which we responded to the Commissioners’ questions about the technique, their concerns about development in the region, water quality, harms to public health, and concerns about fracking moving nations further away from their climate goals. We requested that the Commission urge States to: adopt measures to avoid human rights violations caused by fracking; generate public, truthful and impartial information based on scientific evidence; and protect human rights protections in cases where the technique is advancing blindly. Going forward, we asked that the Commission follow up on the issue, particularly on the negative impacts fracking has on economic, social and cultural rights; on the lives of women, children and adolescents; and on the lives and territories of indigenous peoples. We requested that the Commission follow up on the attacks against human rights defenders and seek protective measures for those at risk. Of course, questions remain, and at the Alliance we’ve identified many more concerns for the region. But this moment has strengthened us. The hearing set regional precedents and made use of the arguments of Advisory Opinion 23, which the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued on human rights and the environment. It is clear that this moment was a small, but vital, step forward, and that there are ears willing to listen. For our part, we will continue doing everything in our power—making use of all available international legal tools—to protect the communities of the Americas that are and could be affected by fracking.

Read more