Environmental racism and the differentiated harm of the pandemic

Photo: Joao Riter on UnsplashBy Tayná Lemos and Marcella Ribeiro

Brazil’s major cities are reopening—with packed bars in Rio de Janeiro and restaurants serving up crowds in São Paulo—despite the lethality of COVID-19, which had caused more than 112 thousand deaths as of August 20.

The reopening of bars and restaurants during the height of the pandemic demonstrates how the virus differentially affects people of different races and socioeconomic levels.

A study by the Health Operations and Intelligence Center (NOIS), an initiative involving several Brazilian universities, found that a Black person without schooling is four times more likely to die from the novel coronavirus in Brazil than a white person with a higher level of education.

Based on cases through May, the study also shows that the overall mortality rate of 38 percent for the white population climbs to nearly 55 percent for the Brazil’s Black population. "The mortality rate in Brazil is influenced by inequalities in access to treatment," Silvio Hamacher, NOIS coordinator and one of the study's authors, told EFE.

Painfully, this trend is repeated in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. This demonstrates that one of the factors behind the high mortality rate of COVID-19 is environmental racism—a phenomenon in which the negative and unintended consequences of economic activities are unevenly distributed.

Unequal Distribution of Damages

The term environmental racism was coined in the United States by researcher Benjamin Chavis, after he observed that chemical pollution from industries was dumped only in Black neighborhoods.

"Environmental racism is racial discrimination in environmental policy-making and enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of color for toxic waste facilities, the official sanctioning of the presence of life threatening poisons and pollutants in communities of color, and the history of excluding people of color from leadership of the environmental movement,” Chavis wrote.

While all activity generates some environmental impact, the territories chosen to carry it out are usually regions located on the outskirts of the city, inhabited by traditional or outlying communities.

In Brazil, environmental racism affects both outlying urban communities and traditional rural communities. And, as in the United States, one of its characteristics is the disproportionate pollution suffered by these minority groups in comparison with the white middle class. This includes the contamination of air and water with toxic agents, heavy metals, pesticides, chemicals, plastics, and so on.

In his 2019 report, Bashkut Tuncak, then-UN Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes, warned that there is a silent pandemic of disease and disability resulting from the accumulation of toxic substances in our bodies.

In 2020, following a country-visit to Brazil, he noted that there is a connection between environmental pollution and mortality from the novel coronavirus and that fewer people would die in Brazil if stricter environmental and public health policies were in place.

"There are synergies between exposure to pollution and exposure to COVID-19. Toxic substances in the environment contribute to the Brazil’s elevated mortality rate," Tuncak affirmed. The underlying health conditions that exacerbate the pandemic are not "bad luck," but largely "the impacts of toxic substances in the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat, the toys we give to our children, and the places where we work.”

An Increase in Vulnerability

Tuncak confirmed that those most vulnerable to the pandemic are the urban poor as well as traditional and indigenous communities, because they are also the most affected by environmental and public health problems. This leads to hyper-vulnerability.

An example of this situation is that of the 17 quilombos (Afro-descendant settlements) in the municipality of Salvaterra, in the state of Pará, home to around 7,000 people. Twenty years ago, an open dump was installed without consulting the families living there. Children, adults and the elderly were forced to live with domestic garbage and toxic and hospital waste, among other refuse. Their vulnerability increased with the pandemic.

Despite the size of the country, there are no territorial gaps in Brazil. When an industry, a landfill, a monoculture, a hydroelectric project, a mine, or a nuclear plant is installed, a historically forgotten community is impacted. The invisible damage of pollution caused by these activities is difficult to prove, but it profoundly affects the health and quality of life of people who live nearby and are already extremely vulnerable.

Another example is that of the indigenous community of Tey Jusu, which in April 2015 received a rain of toxic agro-chemicals spilled by an airplane over a corn monoculture. The fumigation intoxicated people in the community, damaging their health. Unfortunately, the direct ingestion of pesticides by members of communities living near monoculture plantations is a recurring reality. What’s worse is that the current government authorized 118 new agrochemicals during the pandemic, adding to the 474 approved in 2019 and another 32 launched in the first months of 2020.

These pesticides cause several diseases but it is not yet possible to determine their exact consequences on the human body, much less their interaction with other toxic substances or with diseases like COVID-19.

According to an analysis by the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon and the Amazon Research Institute, the death rate from the pandemic among indigenous people in the legal Amazon is 150 percent higher than the national average. The rate of COVID-19 infection among this population is also 84 percent higher than the national average. This is due to historical factors such as the lack of health posts, distance from hospitals, absence of any kind of assistance from the federal government, land invasion, and environmental degradation.

In fact, one of the greatest threats to indigenous communities in Brazil is the invasion of their lands by illegal miners, which causes, among other human rights violations, mercury contamination in water sources. Last year, a study by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation found that 56 percent of the Yanomami Indians had mercury concentrations above the limits set by the World Health Organization, which implies serious damage to public health.

In this sense, environmental racism is a term that exposes a historical separation between those who reap the fruits of economic growth and those who become ill and die due to the environmental consequences of that same economic growth.

The array of systemic damage to the health of these vulnerable communities makes them especially susceptible to the worst effects of COVID-19.

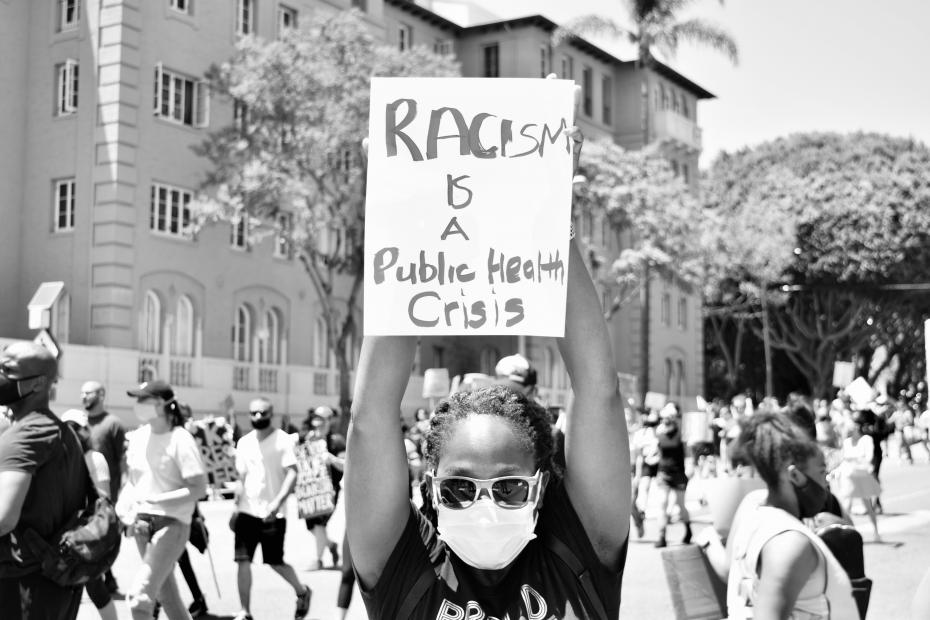

Therefore, in discussing and addressing the pandemic, it is essential to know that it does not reach all people in the same way, that it puts traditional communities at risk of extinction, and that environmental issues are also public health issues.

To overcome the global health crisis, we must bring this racism to the center of the debate.

Tayná das Chagas Lemos

Tayná das Chagas Lemos graduated in with a degree in law from Federal University of Paraíba, Brazil. She was an intern with AIDA's Program on Human Rights and the Environment. In particular, she worked on international litigation against the Belo Monte Dam.