Indigenous People of the Americas Have New Hope for Justice

Credit: Daniel Cima/IACHRBy Astrid Puentes Riaño (text originally published in Animal Político)

June 15 was a historic day. After 17 years of negotiations, the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was approved. That’s cause for celebration.

The Declaration brings advances on many fronts. It means States must commit to respecting the rights of indigenous peoples, including their rights to land, territory, and a healthy environment. It means respecting sustainable development. It recognizes that violence against indigenous women “prevents and nullifies the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms.” And it reinforces the rights of indigenous peoples to participation; to prior consultation; and to free, prior, and informed consent – particularly when they’re faced with harm to their territories.

The need for effective justice

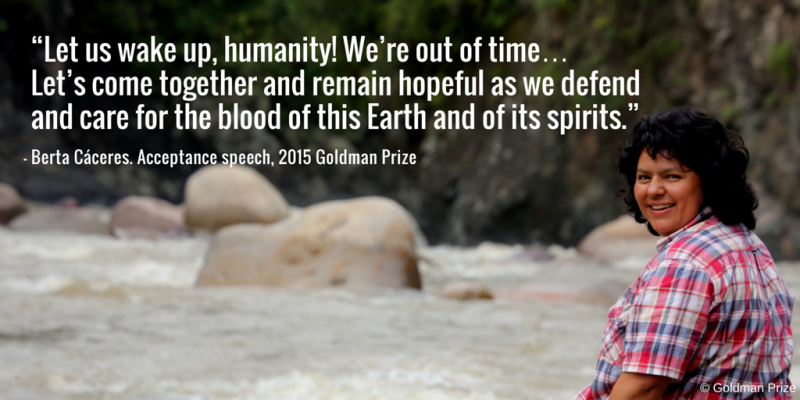

As the Organization of American States was approving the Declaration, activists held a Global Day of Action to call for justice for Berta Cáceres, the Honduran indigenous rights defender assassinated on March 3.

These simultaneous events demonstrate the lack of effective justice in the region. Latin America yearns for justice, particularly with regard to human rights violations caused by extractive, energy, tourism, and infrastructure projects. The events also highlight the urgent need to put declarations and international obligations into practice.

Berta’s death was foreshadowed. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights asked the Honduran government to take precautionary measures to protect her life, which the government did not do. Two days after her death, the Commission also requested protective measures for the organization she led, the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH). Just days later, however, Nelson García, another of the organization’s members, was assassinated.

The primary demand on the Global Day of Action was to create a commission of independent experts to investigate the murders and to help uncover the truth.

The assassinations of Berta and Nelson are not exceptions. More than 100 people dedicated to protecting their lands, forests, and rivers have been murdered in Honduras since 2010. And it’s not only there. Brazil, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Peru are four of the five most violent countries in the world for environmental defenders (alongside the Philippines).

2015 has been widely recognized as “the worst year on record” for those who defend the Earth.

Towards real development

Berta dedicated her life to defending rivers. At the time of her death, she was working to save her people’s territory from being flooded by the Agua Zarca Dam on the Gualquarque River. Indigenous communities there have taken stands against more than 50 extractive and energy projects affecting their land, the majority of which violate national and international law.

Her case has thrust into the spotlight the realities of development in Latin America.

Although governments—with the help of international financial institutions, national banks, and foreign investors—promote extractive, energy, tourism, and infrastructure projects as essential to development and poverty alleviation, the reality is quite different.

Systematically, these projects are built in violation of laws and without adequate planning or evaluation of impacts on the environment and human rights. Sustainable alternatives are rarely evaluated at all. In fact, many of the projects pushed through in Latin America would not be viable in developed countries, where better technologies and safeguards are the norm.

Special Rapporteurs to the United Nations have been calling attention to this issue for years. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights also recognized it in a recent report on extractive industries and their impacts on tribal and indigenous peoples.

Unfortunately, the Commission is undergoing an unprecedented financial crisis because States aren’t making sufficient contributions. Some have delayed or withdrawn funding because of conflicts over the Commission’s rulings on extractive and energy projects in their territories. The clearest example can be found in Brazil, which reacted to the Commission’s call to suspend Belo Monte Dam construction by withdrawing its ambassador, initiating a thorough review of the Commission, and freezing financial contributions. Brazil has yet to re-establish a regular contribution to the body.

Hope and opportunity

For all these reasons, approval of the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is encouraging news. It’s essential that the rights and obligations it contains be upheld immediately.

Starting with Berta’s case, States must demonstrate their seriousness. They must show, through action, that they recognize the problems facing the region; that they’re reaching for truth and justice; and that they favor real development to uplift their people.

Latin America has a historic opportunity. Governments can finally join the 21st Century by respecting the rule of law, practicing what they preach, and promoting development that cares for our natural resources and those who most intimately depend on them.

Astrid Puentes

Astrid Puentes Riaño was one of the two Co-Executive Directors of AIDA (2003-2021). She was responsible for AIDA’s legal efforts and organizational management. Originally from Colombia, Astrid has significant experience linking environmental protection with human rights, and climate change, highlighting the importance to prioritize climate justice. For over twenty years she has been working on public interest litigation, especially in the field of human rights, the environment, and climate change. Astrid holds an LL.M. in Comparative Law from the University of Florida, a Masters in Environmental Law from the University of the Basque Country, and a J.D. from the Universidad de Los Andes, Colombia. Astrid has also taught several seminars and classes on human rights, the environment and climate change, including at American University Law School in Washington, and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM).