A World Without Ozone

By Laura Yaniz

In Mexico, on September 16th, people rest from a night of partying, and so does the sky. In that country, Independence Day begins contaminated by the excessive fireworks used in patriotic celebrations. The irony is that, worldwide, that same day is reserved to celebrate the preservation of the ozone layer. What would have happened had we not decided to care for the ozone?

Each 16th of September, Mexico City wakes up with its air hanging thick and dirty. Although the streets are nearly empty, the government maintains a “Don’t Drive Today” program and sanctions distracted drivers whose plate numbers are forbidden from driving that day.

I call them “distracted” because on holidays, the government often suspends the “Don’t Drive Today” program, but not on September 16th. On this day, everyone must recover from his or her hangover, including the sky.

This is a result of September 15th, when Mexico celebrates its “motherland night.” In cities across the country, thousands of fireworks are launched from plazas packed full of partiers. And so, the next day, the sky hangs even greyer than usual.

It’s a bit ironic that September 16th is International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer. More ironic still is that a Mexican named Mario Molina was part of the group of scientists who discovered what was causing the hole in the ozone layer: chemicals expelled into the air by human beings.

The discovery became a turning point in the war against gases that damage our atmosphere. It led to diplomatic actions worldwide: the Montreal Protocol was signed with the specific purpose of protecting the ozone, prohibiting the use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs, commonly known as Freon) and spurring the elimination of other harmful substances.

“My first environmental panic,” is how Florencia Ortúzar, AIDA climate change attorney, remembers it.

And why not? Destroying the ozone meant weakening protection against the UV rays that cause skin cancer and cataracts, not to mention the fact that extremely dangerous radiation could cause drastic changes in the ecosystems we rely upon in our own lives.

We’ve had 40 years of scientific investigation into the effects of chemicals on the ozone, and 30 years of global and political actions to confront them. Have they mattered at all?

Yes.

The world we avoided

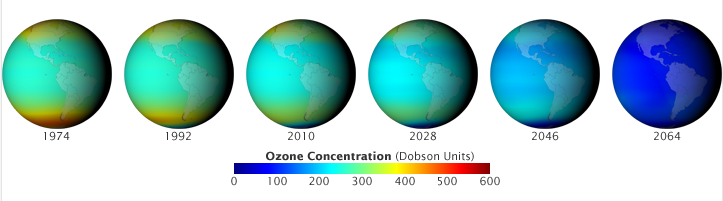

NASA published a simulation that explains the world that might have been had we not acted so quickly to protect our ozone:

- By 2020, 17 percent of all ozone would have disappeared on a global level.

- By 2040, UV radiation would have reached an index of 15 in mid-latitudes. An index of 10 is considered extreme and can cause burns within 10 minutes.

- By 2065, we would have lost two-thirds of the ozone, causing never-before-seen UV radiation levels, which could cause burns in only 5 minutes of exposure.

Would we have reached 2100? NASA didn’t say.

The hope: What we can do

Richard Stolarski, a scientific pioneer in ozone studies and the co-author of NASA’s simulation, expressed his admiration for the global work to confront the problem:

“I didn’t think the Montreal Protocol would work, it was very naïve in terms of politics. Now it is a remarkable international agreement and should be studied by all those involved in seeking a global agreement on global warming.“

Certainly, what was achieved was inspirational, because a catastrophic situation was avoided. But we can’t let down our guard just yet.

When the Montreal Protocol prohibited chlorofluorocarbons, industry replaced them with hydrofluorocarbons. Like the CFCs they replaced, HFCs are potent greenhouse gases. As part of our Climate Change program, we work to reduce emissions of short-lived climate pollutants, which include hydrofluorocarbons.

Although they represent only a small percentage of greenhouse gases, their production and use are growing and will continue to increase if action is not taken. That’s why at AIDA we are working to identify ways to strengthen regulations that reduce emissions of short-lived climate pollutants. Because these pollutants persist in the atmosphere only briefly, reducing their concentrations can provide near-term climate benefit, giving us more time to implement renewable energy and efficiency programs that lessen the severity of climate change.

Are you with us?

Laura Yaniz Estrada

Laura Yaniz Estrada was part of AIDA's communications team. She holds a master's degree in Journalism and Public Policy from the Centro de Investigación y Docencias Económicas (CIDE). She holds a degree in Media and Journalism from the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey (ITESM) and a diploma in National Security from the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM). She is interested in new narratives and environmental security.