Blog

Climate change is real and will have a serious impact on human rights

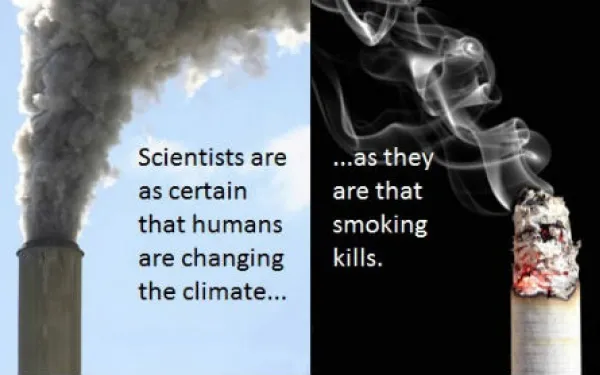

By Héctor Herrera, AIDA legal advisor and coordinator of the Colombian Environmental Justice Network, @RJAColombia The impact of human-induced global climate change is already being felt, and going forward it will have a profound effect on the global population. Many people already believe the phenomenon exists, and they know about its likely impacts. But many others ignore the problem or deny it. In fact, the Climate Name Change initiative has compiled a list of policymakers who still deny climate change in the United States, a country with the greatest emissions of greenhouse gases in the Western Hemisphere. Watch the video Climate Name Change. Source: YouTube New and compelling evidence of climate change was published this year in the first part of the fifth report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which was commissioned by the governments of 195 countries and with input from over 800 international scientists. The most recent IPCC report found that: · The warming of the climate system is ‘unequivocal,’ · The odds that humans are the principal cause of climate change are at least 95%, · The Earth’s average surface temperature rose 0.85ºC between the years 1880 and 2012, · The Earth’s sea level rose 0.19 meters between 1901 and 2010, · Average global temperatures could rise between 1.5ºC and 4.5ºC by the year 2100, and · Sea levels could rise between 26 and 82 centimeters by 2100. There is scientific unanimity on climate change, and it will have a negative impact on human rights. It is worth noting that in 2008 the General Assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS) requested the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to investigate the link between climate change and human rights. Within this framework, AIDA published the report “A Human Crisis: Climate Change and Human Rights in Latin America,” which explains how the impact of global warming affects people’s ability to exercise their basic human rights in Latin America. It concludes that the IACHR should recognize the negative impacts of climate change on human rights and make recommendations to the OAS member states to fulfill their obligations to protect and guarantee human rights as global warming becomes more pronounced. The report mentions that the harmful effects of global warming include the loss of resources such as clean water as well as more extreme floods and storms, rising sea levels, more intense forest fires and droughts, and an increase in the spread of heat- and vector-borne diseases. These impacts, the document states, will have a profound effect on fundamental human rights such as the rights to a healthy environment, food, water, housing and a dignified life. AIDA says that in the face of such a scenario it is important to recognize that some communities are more vulnerable than others because they suffer from poverty or discrimination. The responsibility to take care of these communities is shared between different governments to varying degrees, which is to say that more responsibility falls on the states that have historically polluted the most. In sum, the report recommends that governments and other relevant bodies including intergovernmental organizations and international financial institutions adopt and promote measures to prevent human rights violations brought about by climate change. Althoughthese actions are executed on an institutional level, there are still many things we can do on a personal level. We can become informed of the problem, learn how to mitigate the effects of climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and apply these principles to our everyday lives. For example, you can ride a bike, reduce your electricity consumption or lessen your red meat intake. In short, the scientific community is certain that human-induced climate change is a reality. As AIDA notes in its report, the impact of global warming will seriously affect human rights in Latin America and around the globe. Now is the time to act! To learn more, visit the section on climate change on AIDA’s website.

Read more

The International Coral Reef Initiative and the role of AIDA

By Sandra Moguel, legal advisor, AIDA, @sandra_moguel Made up of government representatives, scientists and civil society members, the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) meets annually to discuss and make decisions on priority issues regarding the protection of international coral reefs. This year the meeting was held in Belize from October 14 to 17, hosted by ICRI Secretariat co-chairs Australia and Belize. The ICRI describes itself as an informal partnership between nations and organizations. It was created out of concern for the degradation of coral reefs, mainly as a consequence of human activities including land pollution, anchoring and more. Its objectives are to: 1) Encourage the adoption of best practices in the sustainable management of coral reefs and associated ecosystems; 2) Build capacity; and 3) Raise awareness at all levels on the plight of coral reefs around the world. Although ICRI decisions are not binding among members, they have been crucial in highlighting the important role of coral reefs and similar ecosystems in guaranteeing environmental sustainability, food security and social and cultural welfare. In its own documents, the United Nations has recognized the work and cooperation efforts of the ICRI in the international area. Much of AIDA’s work runs in parallel with the ICRI’s efforts. AIDA’s Marine Biopersity and Coastal Protection Program aims to ensure that Latin American coral reefs are legally protected and managed in a way that safeguards their biological integrity. This was reason enough for us to apply for ICRI membership so we could take part in this platform for dialogue. By participating in Belize, AIDA sought to identify opportunities to expand our work in high-priority countries and islands in the Americas. We also think it is important that the ICRI should take into account our expertise in international law and our partnerships with participating organizations. It is also key to apply a legal framework to the ICRI discussion, and there are some interesting ad hoc committees involved in the initiative that could explore this aspect. We are particularly interested in the economic value of coral reefs and similar ecosystems, a topic that also addresses the issue of compensation. Another interest is in the law enforcement committee that performs research on the assessment of the evidence and standardization of rules in different countries. Colombia, Costa Rica, Granada, Panama and the Marine Ecosystem Services Partnership (MESP) all attended the ICRI meeting in Belize as new members. Ricardo Gómez, Mexico’s representative to the ICRI, made a formal presentation of his paper entitled Regional Strategy for the Control of Invasive Lionfish in the Wider Caribbean[1]. In addition, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) presented its paper Status and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs: 1970-2012, edited by Jeremy Jackson, Mary Donovan and others. The paper looks at the changing patterns in coral reefs such as overfishing, coastal pollution, global warming and invasive species. The analysis concludes that rising tourism and overfishing are the most apparent causes of coral decline over the past 40 years. Coastal pollution is undoubtedly increasing, but no specific data are available to properly estimate its effects. Global warming also is a threat, but its effect was found to be of limited importance for now in the study. As a result of the study, the delegates approved a motion to ban fish traps, spearfishing and parrotfish fishing throughout the wider Caribbean and its adjacent ecosystems, and provide economic alternatives for affected fishermen. It also prompted a proposal to increase co-management agreements between government and civil society. At the meeting the delegates also discussed a simplification and standardization for monitoring the reefs and to make the results available in a database to facilitate adaptive management. It would be accompanied by a data exchange for local managers to benefit from others’ experiences. At the closing of the event, the delegates revised the ICRI Action Plan and held a ceremony to transfer the Secretariat responsibilities to Japan and possibly Thailand, which will be in charge of the administration of the ICRI in 2014. I really enjoyed working with my colleague and friend Haydée Rodríguez, another legal advisor at AIDA, who I talk with on a daily basis even though we live in different countries. I very much enjoyed discussing the scientific and management aspects of the coral reefs with experts in the protected marine environments of different countries. Although faced with similar problems, they resolve them in different ways because the same solutions cannot always be replicated in different contexts. In my point of view, the biggest challenge the ICRI faces is financing its platform. I also think it’s important to invite new members to encourage a greater representation from the government, scientific and civil society communities. [1] ReadEl Pez León y la necesidad de combatir especies invasoras(in Spanish, 20-noviembre-2012).

Read moreDams, mines threaten indigenous rights: Recommendations from UN human rights expert

By Jessica Lawrence, Earthjustice's research analyst A longstanding goal of Earthjustice and the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA) has been to sound alarms at the United Nations, in national courtrooms and in international fora such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights about environmental and human rights violations associated with mines and dams. Indigenous peoples are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of such extractive and energy industries in their territories. Last April, Earthjustice and AIDA provided evidence of these harms, as well as recommendations about how to avoid them, to U.N. indigenous rights expert James Anaya, who recently issued a report on extractive and energy industries and indigenous peoples. Comments from Earthjustice and AIDA focused on mine closure, describing how inadequate closure, restoration or monitoring can cause severe, long-term environmental contamination that can violate indigenous and human rights. We identified steps that countries can take to prevent these problems, including enacting strong laws on pabipty of mine operators and requiring operators to provide financial guarantees to ensure adequate clean-up during and after mine closure. Such measures can help protect human rights to health, clean water and a clean environment, as well as indigenous rights to culture, food, a means of subsistence and their lands and natural resources. Anaya’s report includes a number of recommendations with environmental and health imppcations. Key recommendations include: Guaranteeing indigenous communities’ right to oppose extractive and energy projects without fear of reprisals, violence, or coercive consultations. If a government decides to proceed with a project without their consent, indigenous communities should be able to challenge that decision in court. Rigorous environmental impact assessment should be a precondition. Indigenous communities should have the opportunity to participate in these assessments, and have full access to the information gathered. Governments should ensure the objectivity of impact assessments, either through independent review or by ensuring that assessments are not controlled by the project promoters. Measures to prevent environmental impacts, particularly those that impact health or subsistence, should include monitoring with participation from the pubpc, as well as measures to address project closure. If governments and project operators followed Anaya's recommendations, it would substantially reduce the harm caused to indigenous peoples by the often shameful and irresponsible conduct of extractive and energy industries. AIDA, to which Earthjustice provides significant support, works with local communities to address human rights violations from extractive industries throughout the hemisphere, including the Barro Blanco dam in Panama, the Belo Monte dam in Brazil, the La Parota dam in Mexico, and mines in the Andean ecosystems of Colombia.

Read moreFrom Anton’s Valley to Altamira: It’s Been a Great Decade with AIDA!

By Astrid Puentes Riaño, AIDA Co-Director , @astridpuentes November 1 marks my 10th anniversary working with AIDA! It’s been a decade since the board of directors, meeting in Anton’s Valley, Panama, decided to hire me. I was thrilled with the offer: when I was a law student in Colombia and an assistant with the NGO Fundepúblico, I had participated in the founding of AIDA and in setting up its first meeting, in 1998. Over the past decade, I have had the great fortune to meet wonderful people and to visit extraordinary places in Latin America— Cordoba in Argentina, Altamira in Brazil, Los Altos de Jalisco and La Parota in Mexico, La Oroya and Iquitos in Peru. Today, as I celebrate and renew my commitment to keep learning and giving my best to AIDA, I am grateful to be able to provide a positive contribution to the region. AIDA was and is my dream job! A big challenge from the beginning When the AIDA board appointed me, it was more for the potential they saw than for my experience. I did my best, contributing my energy and passion to the expansion of environmental law and to promoting an understanding of the link between human rights and the environment, all while raising a family. Ten years later, and thanks to this incredible opportunity, I can say that I have made some mistakes, learned, grown immensely, and come to understand the sometimes-harsh reality of our environment in Latin America. It seems that the board of directors is happy with the results, because I’m still here! How much we have grown! When I started, AIDA was just Anna Cederstav (co-executive director) and me, working with a budget of approximately U.S. $300,000, a small office within the Earthjustice headquarters in California, and four cases. We had many dreams for AIDA. The main goal was to make it a solid regional organization that works on emblematic legal cases, always giving highest priority to the people and communities in the most vulnerable situations, and with about ten lawyers in key countries who stand out for the quality of their work and effective collaboration. Today our team includes 11 attorneys, one scientist, and 10 administrative and communications professionals, based in seven countries. We work every day to promote greater protection and environmental justice and to encourage regional economic development that does not sacrifice our natural resources or our future. Some milestones I’ve been extremely pleased that we’ve helped to improve several areas and communities in the region. For example, we’ve helped achieve: ▪ Official recognition of the environmental and human health disaster in La Oroya, Peru, where the 70-plus people we represent have begun to receive some medical attention from the government; ▪ A significant decrease in the aerial spraying of coca and poppy plants in Colombian national parks; ▪ Protection of leatherback turtles and one of their last remaining nesting sites in Costa Rica; ▪ Increased awareness of the human rights violations suffered by thousands of indigenous people living near the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam in Brazil; ▪ Suspension of a mega-tourism project in Baja California Sur, Mexico that would destroy the Cabo Pulmo Coral Reef, known as the world’s aquarium; ▪ Amendments to the Mexican Constitution to include human rights protections and to improve the recognition of the human right to a healthy environment. In addition, we have published a trilingual guide on how to apply human rights mechanisms to environmental cases; a report on the human rights impacts of climate change in Latin America; and a report on how large dams are not a panacea but instead are having a negative impact on millions of people in our region. We also have organized periodic workshops with our colleagues that emphasize the inseparable link between human rights and the environment. The best aspect of my job over these years has been learning more about the region and every person I have met along the way. In 2004, for example, I took my first trip to La Oroya, where I met Pedro and Juan*, brothers both under 10 years old whom we represent before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. With high spirits, they attentively took part in our workshop aimed at protecting their rights, although they nearly fell asleep while eating their soup at lunchtime—one of the effects of lead poisoning. Now teenagers, they have begun their professional careers; Juan is serving in the military, and Pedro in the process of starting the university. Then there are Juanita and Margarita*, who were not yet born in 2004. I got to know the girls during later trips to La Oroya; when I first met them they arrived with their mothers, wrapped in slings. Now they are nearly teenagers and we have developed warm personal relationships that go beyond our legal work with them and with many others. Not everything has been rosy It hasn’t all been happiness and celebration. Over the past 10 years I have sadly witnessed: ▪ Construction of the Baba hydroelectric dam in Ecuador, despite a Constitutional Court ruling that ordered review of the environmental assessment because the project violated constitutional and international laws; ▪ Construction of El Zapotillo Dam in Los Altos de Jalisco, Mexico, although it seems for now that Temaca, a town that authorities had planned to flood, won’t be destroyed; ▪ Start of construction of the huge Belo Monte dam in Brazil, in defiance of the precautionary measures issued by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights; ▪ Exponential growth in mining projects, including in the Colombian páramos—unique high-altitude ecosystems that provide fresh water for much of the population. What comes next If I weigh the good and the bad, the overall balance is positive. For now, a great part of our dream has become a reality. But just as today’s challenges have become greater, so has my commitment to see through our goals for the region. I extend my sincere thanks to the AIDA board and to Anna, my co-director, as well as to our great team and everyone who has collaborated with AIDA in the past. And I thank my family, friends and our donors, including the foundations and friends who have each managed to donate something, no matter how large or small. Thank you for your generosity and for helping us to fulfill our dreams and change the world together. All of the successes and challenges make the gray hair and wrinkles worth it. I’m ready for many more years at AIDA, as long as I continue to be an effective agent of its success! *Names have been changed to protect the identities of the people mentioned.

Read more

"A full belly makes a happy heart": How does food waste affect the environment?

By Gladys Martínez, legal advisor, AIDA It’s the weekend and we’re at the beach in Costa Rica. The sun is shining, we’re surrounded by nature and listening to the sound of the sea as we enjoy a delicious traditional breakfast of tropical fruit, gallopinto (rice and beans), eggs, home-made tortillas and coffee brewed in a cloth filter. I wish I could say, “And we lived happily ever after". But I can’t. I get upfrom the table to see a heapof leftovers... The problem of food waste and its impacts On World Environment Day this past June 5, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) presented alarming data about the impact of food waste on the environment. In the report Food wastage footprint: Impacts on natural resources, the FAO states that food production accounts for: - 25% of the earth’s surface, - 70% of water consumption, - 80% of deforestation, - and 30% of the greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. The report notes that producing one liter of milk requires 1,000 liters of water! This means that pouring a glass of milk down the sink is equivalent to dumping 250 liters of water. Throwing out one hamburger is like tossing more than 60,000 liters of water. In terms of total food wastage, 54% is generated during the production, handling and storage at harvests. The remaining 46% is generated during the processing, distribution and consumption of food. The direct economic cost of food wastage is estimated at more than USD $750 billion annually. This figure seems unthinkable on a planet where one in every seven people go hungry and more than 20,000 children under the age of five die from hunger every day. A lot can done inpidually and as a country Costa Rica has campaigns aimed at motivating people to consume responsibly and raise awareness about sensible eating to preserve the environment and other people’s right to food. Working together with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEp) and the FAO on the campaign Think.Eat.Save, Costa Rican singers Debi Nova, José Cañas (in Spanish) and Manuel Obregón (in Spanish), who doubles as the country’s minister of culture and youth, composed a song against food wastage called “Alimento para el alma” (“Food for the Soul”). ”Food for the Soul" video (in Spanish). Source: YouTube The Food Bank (Banco de Alimentos) is another Costa Rican initiative. Fourteen private companies have agreed to donate products unfit for sale because of damaged labels or packaging. The social and environmental awareness of these companies has made it possible for 15,169 poor people to receive about two plates of food every day over the past year and a half. What can I do at home? Everyone can helpreduce food waste. The campaign Think.Eat.Save offers these helpful tips: ▪ Purchase wisely: Don’t buy more than you need and choose products withless packaging. ▪ Better planning: Cook what you can eat and freeze the leftovers to eat later. ▪ Support distributors of organic and “wonky” fruits and vegetables. Eating organic food has a minimal impact on your health and the environment, and misshapen fruits and vegetables still taste delicious even if they do not look perfect. ▪ Read food labels carefully so as not to throw away perfectly good food. Nine out of 10 people throw out food because they don’t understand what the labels mean.Did you know that if you put an egg in a bowl of water and it floats, that means the egg is bad? If it sinks, it’s still edible. Find out more at FixFoodDates.com ▪ Reduce your food waste and compost what you don’t eat. You can find more useful advice at thinkeatsave.org. Bon appétit!

Read more

What are the páramos and what can you do to protect them?

By Carlos Lozano, legal advisor, AIDA, @CLozanoAcosta What are páramos? The answers to this question are the very reasons why we must support their conservation. They are rare and unique ecosystems. The páramos provide an environmental service to more than 100 million people. They possess the greatest botanical biopersity of all high-altitude ecosystems: 60% of their plant species are endemic (that is, they are found only in the páramos). Their formation is a slow and steady process that has taken hundreds of thousands of years. Although the Colombian páramo is considered tropical because it is situated near the equator, the climate is not hot. It is rather cool due to its high altitude of 3,000 meters (9,842 feet) above sea level. The páramo is a geographical paradox: a frosty ecosystem found in a tropical zone. It alsois an incredible beauty. They form a major part of Latin American history. The páramo was dubbed “the land of the mist” by the conquistadores. The indigenous inhabitants incorporated the páramo in traditional ceremonies as it was considered to be a sacred area. The Muisca people of Colombia’s central highlands believed that the páramo gave birth to their primordial mother, the mythological Bachué. The famous legend of El Dorado also originated in the páramo; A Muisca chief was said to have covered himself in gold and thrown himself into Lake Guatavita, prompting the conquistadores to go on a great gold rush in the search of his treasures. During the Colombian War of Independence, Simón Bolívar crossed the Pisba páramo to elude Spanish army sentinels stationed on the main roads. They are a vital water source and a carbon sink that combats climate change. The páramos feed streams, rivers, aquifers and water catchment areas. These in turn supply water to major South American cities including Bogotá and Quito. The páramo also have a remarkable ability to store water through its vegetation and unique geological and ecological features. It also acts as a carbon sink, accumulating carbon through organic matter in the soil. Invasive activities like mining have a detrimental impact on this process by releasing carbon stored in the soil, contributing to global warming. These points demonstrate how the páramos play an important role as a vital source of water and an ally in combating climate change. Their protection is crucial for our future. In Colombia, where more than half of the world’s páramos are located, the government is making a decision on the future of these valuable and fragile ecosystems through a process of officially demarcating their territorial boundaries. Despite the ecological and environmental importance, the boundaries of the Colombian páramos still have not been defined. This poses a serious risk to the area as it is left vulnerable to harmful activities that could destroy it. To truly protect the páramos from irreparable damage it is essential to clearly define its territorial boundaries. The Santurbán páramo, located between the departments of Santander and North Santander, will soon become the first area to be officially demarcated, according to government plans. Mining interestsalready pose a threat to the area. What is urgent now is for Colombia’s minister of environment to demarcate the Santurbán páramo territory based on scientific criteria. AIDA is taking online action to call for this proposal. With YOUR SIGNATURE, you can support the cause and pressure the government to protect the páramos. Join us to protect the páramos!YOU CAN SIGN too (in Spanish)!ASK Colombia’s president and minister of environment to properly delineate the Santurbán páramo NOW! #SaveSanturbán

Read moreHow to end the reign of plastic bags and learn to take care of our environment

By María José Veramendi Villa, senior attorney, AIDA, @MaJoVeramendi Some months ago my colleague at AIDA, Haydée Rodríguez, wrote an interesting post in this blog called Plastic bag? No thank you (Spanish only). I confess that it shocked me to read the post because although I had a general idea of the harmful effects of plastic bags on the environment, I didn’t realize the profound damage they can cause. This made me reflect on Peru, where plastic bags reign supreme, and where there is very little public awareness of their harmful impacts, that they poison and kill marine wildlife and pollute the environment, among other things. In most shops, almost all products are packed in plastic bags no matter how small. Some statistics An investigation entitled the Study on the Perceptions, Attitudes and Environmental Behavior regarding the Unnecessary Use of Plastic Bags was carried out in two districts of Lima. The results, published in a July 2012 article on the Ministry of the Environment's website (Spanish only), found that 94% of the businesses studied used plastic bags exclusively to package their consumer products, while 60% used between one to three plastic bags for every purchase and 36% used three to six. The article announced the launch of a campaign to reduce the use of plastic bags in the northwestern province of Piura, called “Healthy Living with Health Bags.” Other than this article, I couldn’t find any further public information on the campaign’s impact or whether it had changed people’s behavior, something that would have made it possible to gauge if the campaign had the potential to be replicated elsewhere in the country. The day to day In most Peruvian supermarket chains, plastic bag usage is exaggerated. Sometimes checkout assistants pack small items in separate plastic bags, generating a huge amount of unnecessary plastic. A few months ago I visited a well-known Lima supermarket and asked the clerk why they didn’t attempt to cut down on plastic bag usage. I suggested that the supermarket should charge money for plastic bags as an incentive for people to bring reusable bags made of cloth. He said, “Oh, if we did that people would stop coming… There are people who ask us to use more bags or double bags, and if we didn’t, they’d call us stingy.” Attitudes like this illustrate the disregard that various sectors of Peruvian society have for environmental protection. Biodegradable bags? In 2007, Peru’s largest supermarket chain, Grupo Wong, which owns the Wong and Metro supermarket chains and is now owned by Chile’s Cencosud, introduced the use of biodegradable bags, a practice then replicated by other supermarkets in the country. Wong bags come with a caption that reads, “This bag will biodegrade without leaving any contaminant residues.” The manufacture of the bags “includes a special additive that causes the bag to disintegrate into smaller pieces when it comes in contact with oxygen, sunlight and friction, a process which then allows microorganisms such as fungi or bacteria to feed on its remnants, converting the bag into water, biomass, salt minerals and carbon dioxide, just as we do when we exhale air,” Wong says on its website. A real alternative? The bags used by Wong supermarkets seem ordinary enough. The difference is the special additive ingredient that accelerates the disintegration of the bag. “This means that the plastic is broken down into smaller particles that are so small that you can’t see them. In the first phase, the waste cannot be assimilated with plants (Spanish only)”. Inapol, a Chilean maker of conventional and biodegradable plastic bags, says that while “a conventional plastic bag takes about 300 years to biodegrade, our bags that contain the special oxo-degradable additive reduces this time to approximately two years, depending on the external factors that accompany the process. Exchange of contaminants According to a European Bioplastics study, the additives in the oxo-biodegradable bags consist of chemical catalysts thatcontain transition metals like cobalt, magnesium and iron, among others. In this process the disintegration of the plastic bag is caused by a chemical oxidization of the plastic’s polymer chains, triggered by UV radiation or heat exposure. According to the study, the waste would eventually biodegrade in the second phase. The study points out that the breakdown of the biodegradable plastic bag is not a result of natural biodegradation but of a chemical reaction. The waste remnants remain in the environment, something that does not present an adequate solution to the problem. It only transforms visible waste particles into invisible contaminants. There have been significant advances and an increase in awareness in the business community on the need to take care of the environment. But doubts remain about the natural biodegradation of plastic bags such as those used by Wong supermarkets, and whether they present a real sustainable solution for the environment. As Peru is such a creative and perse country, why shouldn’t it adopt alternatives to plastic packaging such as reusable cloth bags and recycled materials, and employ their use across the country? Isn’t this something to think about? We must change our mentalities for things to improve. To paraphrase Haydée, we need to say, “No thank you” to plastic bags. We should learn to reuse and recycle so that we can take care of what we love and, above all, where we live.

Read moreThe UPOV Convention and the privatization of seeds: What’s at stake?

By Florencia Ortúzar, legal advisor, AIDA "Modern agriculture is not a system for producing food but for producing money"(Bill Mollison: Australian researcher, scientist, teacher, naturalist and the father of permaculture). Seeds are the beginning of life itself. They are the means of nature’s propagation and the building blocks of life. Patenting seeds hands their ownership rights to a select few, and this causes great resentment among many. What does all of this really mean? The UPOV: An international convention The International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) is an intergovernmental organization whose objective is to grant intellectual property rights to “breeders.” That is, to people who have created or discovered new varieties of seeds. Some countries in the Americas have signed the UPOV Convention, which was established in Paris in 1961 and revised three times (the latest in 1991), and others are considering it. A seed needs to be considered a new variety in order to be patented. New varieties can be generated through the use of traditional techniques or genetic modification in laboratories. It is difficult to measure the possible ramifications of something so new and novel as the privatization of the life contained in a seed and, for good reason, many people are worried. The situation in Chile (and other countries): To join or not to join? Chile’s Congress is currently debating legislation known as the “Monsanto law” that, if passed, would implement the UPOV Convention and the ability to patent new seed varieties. This means that someone could alter the genetics of a native seed to become its inventor and owner. This would give them the right to sell it, charge a fee every time the seed is used, prohibit its trade in the market and draw up a contract dictating what farmers can and can’t do with the harvested product (for more information, you can listen to the interview (in Spanish) with the co-founder of the NGO Chile sin Transgénicos (Chile without Transgenics)). Proponents of the law argue that it is a necessary protection to encourage innovation in the country's agriculture sector. Concerns Making native seeds obsolete: What chance does a native seed have for survival competing against a seed that is genetically modified to be more productive and efficient? According to market rules, the “new” cultivated seeds will displace the native ones. Even worse, GM crops could easily contaminate the remaining natural varieties. Monopolies: Those with the resources to create new seeds, especially genetically modified ones, which are the most profitable, are typically the huge corporations that today dominate the production of GM foods, like Monsanto. If the seed patent system were authorized in Chile, these companies would get a free pass to take control of the country’s cropland as they have already done with great efficacy in Argentina. What is more, the most profitable companies would gain access to the country’s most arable land, expanding monoculture practices while also forcing less profitable seeds out of the market even if they are more nutritional. Seed exchange: The “Monsanto law” grants great power to the seed owner by binding the seed purchaser to a contract that controls the entire harvest and the new seeds that are generated. Traditional practices such as the propagation, sale, gift giving and exchange of seeds, customs as old as agriculture itself, would be prohibited. The law would strip farmers not only of an essential part of their job but also a key source of income: the sale of cultivated seeds. As a consequence, the farmer would lose power and identity and become a mere cog in the corporate machine. Genetically modified crops: To the benefit of big companies, we inevitably favor the entry of genetically modified foods, the products with the greatest economic return. While the adverse side effects of eating GM food are not yet officially known, it seems wise to err on the side of the precautionary principle and avoid uncontrolled testing on humans. The advent of this law would protect GM crops. Natural products, which are less economical but generally more nutritional, would be overtaken by more productive seeds. There are many reasons to treat GM foods with caution. Rather than helping to end world hunger, we have increased the use of pesticides, destroyed biopersity, caused inequality between farmers and contaminated native varieties of seeds. It also is dangerous for people’s health to live near GM crops, as has been proven in Argentina. Environmental impacts: By allowing seed monopolization, crops will become homogenized to achieve the most economic harvests. This will lead to monocultures, many of them pesticide-resistant seeds that will require the use of alarming amounts of agrochemicals. Of particular concern, a lack of persity means crops become less resilient and adaptable to environmental changes, including those associated with global warming (You can read here (in Spanish) an article about the problems Argentina is experiencing with the expansion of GM soy monoculture). Unforeseeable risks: If a country drastically changes its agricultural system, the risks are difficult to predict. It is possible that a company could incite a plague that would force desperate farmers its new seed that is resistant to the plague. Another risk is that farmers could be unfairly penalized for using patented seeds, especially if farmers have not been properly educated about the new legislation. Could farmers face lawsuits, convictions and the burning and seizure of their crops? Conclusion The implementation of the UPOV Convention threatens to drastically change an essential part of the natural cycle. The most dangerous aspect is that the global initiative is attracting more followers. It does not seem fair that a person can pay a fee for a seed that should never really be the creation of a person. Although the “breeder” could have changed a gene, it should not give him the right to copyright and control the rest of the seed’s genetic information. In Europe, only two countries have permitted the entry of GM crops. Chile has enormous potential to produce organic crops, and it could position itself successfully in the European market. But the Chilean authorities haven’t considered this as a possibility. The approval of the patent law on new seeds favors multinational seed monopolies, and this would allow the entry of GM crops that would displace and contaminate original varieties without the possibility of turning back. On the contrary, Peru recently passed a law banning the import and production of GM crops for 10 years. This is a good example to follow.

Read more

Virtual water: What we do not see

By Haydée Rodríguez, legal advisor, AIDA We live in an era of virtual creations. We have virtual reality, universities and conferences and even virtual pets. It’s no surprise then that the term “virtual water” is used more and more. But what does it mean and what’s it got to do with our everyday lives? Virtual water is defined as the quantity of water needed to create a certain product. This estimate takes into account the volume of water consumed and contaminated in the different stages of the manufaccturing process. The United Nations estimates our daily water requirement is 2 to 4 liters per person. But it takes 2,000 to 5,000 liters to make the food that one person needs every day. The Virtual Water Project has made estimates of the virtual water needed to make many of the products we consume daily. You can even download an application to do the calculations on your mobile phone. Here are a few numbers that caught my attention: 15,000 liters of water are needed to produce 1 kg of meat. 8,000 liters of water are needed for a pair of jeans. 1,000 liters of water are needed for 1 liter of milk. 2,500 liters of water are needed for 500 g of cheese. 25 liters of water are needed for 1 potato. 3,600 liters of water for 1 kg of rice. 109 liters of water for 1 glass of wine (125 ml). Our water footprint The virtual water calculation allows us to measure our water footprint as well. The water footprint of an inpidual, business or country is the sum total of the virtual water used in making every product and service. On a per-country basis, the calculation includes the water used for domestic and industrial purposes as well as the water used in foreign countries to produce the goods and services imported and consumed by the country's inhabitants. The map above shows the water footprint by country on a world scale (you can check out the data of every country here). It is interesting to note that developed countries like Canada that have a high level of manufacturing and imports also have a very high water footprint. Even so, according to the United Nations water availability map, not all the countries listed suffer water shortages. In general, this is becuase many products requiring high levels of water are imported and not manufactured locally, thus generating greater pressure in countries suffering from water stress: high water demand with low availability due to shortage or pollution. You can also calculate the water footprint of inpiduals taking into account social characteristics and consumption patterns. If you want to calculate yours, you can enter your data on this link. Virtual water, real action Being aware of the concepts of virtual water and water footprint is important for promoting the need for more information and transparency regarding what we consume. That makes it possible for us to change our habits and choose more sustainable products with low virtual water content. We can always ask ourselves what's behind the scenes for the pair of jeans we want to buy but may not need. Both concepts are essential for designing any strategy for protecting water and reducing the impact on aquatic ecosystems. Countries should consider the virtual water content of imported and exported products in their water resources management plans. There is still much to learn in this field. The virtual water coming from aquifers or páramos can have a higher value and impact on populations and associated ecosystems than surface waters. To have a better idea of the pressure we put on water resources we should incorporate the economic value of the environmental services offered by the difference sources into the calculation of virtual water. Virtual water is a tool we can use to understand the impact we have on natural resources. Even beyond what we can see, water is present in all our activities and decisions. By taking action to protect our water resources and making informed decisions, we can guarantee the human right of access to water for many people around the world.

Read more

Why defend the environment?

By Tania Paz, general assistant, AIDA,@TaniaNinoshka “The earth will be as the men are.” (Nahuatl proverb) “They murdered a friend of the collective in Amatlán,” read the text message I received on the afternoon of August 2. They had killed Noé Vázquez Ortiz, an artisan, farmer and member of the Defensa Verde Naturaleza para Siempre (Green Nature Forever Defense) collective, a group of citizens from Amatlán de los Reyes, a municipality in Veracruz, Mexico. Since 2011, the collective has been fighting against the construction of the El Naranjal hydropower dam, a project that will disrupt rivers and affect the livelihoods of some 30,000 people in five neighboring municipalities. Noé was killed while gathering flowers and seeds for the opening celebration of the 10th anniversary of the Mexican Movement Against Dams and in Defense of Rivers (MAPDER). I never met Noé and I’ve never visited Amatlán de los Reyes. But for the past three years I have been following the struggle of the Amatlán people to protect their land. The tragedy prompted me to ask myself: Why should we defend the environment, and what motivates people to risk their lives for it? There are important reasons why it’s essential for us to defend the environment, which I am sharing here. While this is not an exhaustive list, I think it does help at least to explain key motivations. The right to a healthy environment The right to live in a healthy environment was established in the 1972 Stockholm Declaration and reaffirmed in the Rio Declaration of 1992. This right encompasses others such as the right to life, the right to food and food security, access to drinking water and sanitation through the protection of water sources, forests and wildlife. Environmentalists are more than anything defenders of human rights, as AIDA attorney María José Veramendi has said. The defense of our identity as communities Natural resources have played an important role in the development of civilizations throughout human history. This is manifest in the construction of community culture and identity. The legends, stories, traditions and characteristics of the Mesoamerican communities, for example, are intrinsically linked to the gifts of nature. During Easter in Nicaragua, children re-enact the crucifixion of Jesus Christ in an aquatic Via Crucis (in Spanish) (Stations of the Cross) on Lake Nicaragua, the largest freshwater source in the country, while the river system is an important aspect of the famous Mexican legend of “The Weeping Woman.” In the Rarámuri territory of Mexico, “corn provides the backbone of the indigenous Sierra Tarahumara culture as it does for all ethnic groups in the country. Any changes involved in the production, consumption and distribution of the grain signifies a transformation in the social, cultural and biological persity of these ethnic groups,” says Horacio Almanza Alcade (2004, in Spanish). What will happen to our cultural wealth and identy when natural resources are depleted? Will we lose our identities as communities? These questions are worth asking. The continuity of the human species For me, defending the environment is a way to preserve the human species with a high standard of living and quality of life. In a well-known letter from 1854, Chief Seattle of the Suwamish tribe wrote in reply to an offer by US President Franklin Pierce to buy the country’s northwest territories the following: “Whatever befalls the earth, befalls the sons of the earth. If men spit upon the ground, they spit upon themselves.” Today, the harm we are inflicting on the environment comes at a great cost. According to the most recent estimates (2013) of the World Health Organization (WHO), more than two million people die each year from inhaling small particulate contaminants in the air both indoors and outdoors. Malaria kills over one million children under the age of five every year, mostly in Africa. The spread of the disease is worsened by poor water storage and handling, inadequate housing, deforestation and the loss of biopersity. Defending the environment is no easy task. At every level, whether in communities, national or international organizations, civil associations or NGOs like AIDA, tackling the problem requires many hours of work and study at the sacrifice of time away from family and friends. In many cases, environmental defense means risking lives for the sake of others, for the sake of society. Protection is needed. It is the obligation of governments and authorities at home and around the world to provide this necessary protection and support to the defenders of the environment.

Read more