Blog

The Nicaragua Canal: Resistance to Dispossession

“How do I explain do my son that to be a landowner will soon mean to be an employee?” asked a woman who may soon lose her land because of the proposed Nicaraguan Interoceanic Grand Canal. Her question resounds in my head each time I hear news of the canal’s construction. There is nothing more valuable than a piece of land to cultivate, land you’ve dreamed of your whole life, land that your children will some day inherit, land that makes the early mornings and long days working under the hot sun worth it. People throughout Nicaragua have said “no” to the proposed canal. They have decided to fight because they’re not willing to lose their dreams for nothing more than the promise of a job. A Controversial Canal The proposed canal will cross Lake Nicaragua, or Cocibolca, the second largest lake in Latin America. It will cut the country in two to connect the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific. At 278 kilometers, it will be three times larger than the Panama Canal. The project’s estimated cost is 50 billion dollars. More than just the canal, it will include other megaprojects: an airport, highways, a free trade zone, resorts and two ports – one on the Pacific and the other on the Caribbean. The magnitude of the project will be reflected in the negative impacts it will cause. Canal construction will directly affect 119,000 people in 13 municipalities, according to Mónica López Baltodano of Fundación Popol Na. She presented this information at a special hearing on March 16, 2015 before the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights. The hearing was requested by 10 organizations from Nicaragua and the multi-national Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL). “Our greatest worry is that the exact number of citizens who will undergo a process of expropriation (those who will be displaced from their land) remains a State secret, and there are no plans for relocation or the restoration of living conditions,” Lopez explained. Azahelea Solís of the Citizens’ Union for Democracy (UCD) added that granting licenses for the project “violates the Constitution of the Republic, various national laws, and more than 10 international environmental treaties signed by Nicaragua.” In addition, the canal was approved in the absence of an environmental impact assessment. The concession was granted to a single company: the Chinese consortium HKND. In the hearing, Louis Carlos Buob of CEJIL explained that the consortium has exclusive rights to “development” and “operation” of the canal, potentially for at least 116 years. The concession gives them “unrestricted rights over natural resources like land, forests, islands, air, surface and groundwater, maritime space and additional resources that could be considered relevant anywhere in the country.” The damage to these natural resources is precisely the most worrying thing about the canal. Its construction will impact Lake Cocibolca, the most important fresh water source in Central America. It also “threatens sensitive marine ecosystems in the Caribbean Sea belonging to Colombia and divides in two the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, a loose network of reserves and other land that stretches from the south of Mexico to Panama, which animals such as the jaguar use to cross Central America.” Community Resistance Those affected by the expropriations have formed the National Council for the Defense of our Lands, Lake and National Sovereignty. Through this united front they have expressed their total opposition to the project and have stated that they will not sell their lands for the canal’s construction. According to the page Nicaragua sin heridas, a citizen’s initiative to disclose information on the project, there have been 41 protests against the project, in which 113,500 people have mobilized across 25 territories in just five months. The community of El Tule, in the department of Rio San Juan, has become an emblem of the anti-canal fight. The citizens there who will be affected by the project have held marches and rallies. On December 24, they were victims of repression at the hands of the National Police – the crowd was beaten and 33 people, including leaders of the movement, were imprisoned for their protest. In Tule there was no Holy Night, and no Merry Christmas. A Disastrous Trend Sadly, the Nicaragua Canal is just one of many projects that gravely affect human rights and the environment in Latin America. In the last 20 years, more than 250 million people have been displaced in the name of “development” for megaprojects, such as dams, or extractive activities, such as mining. In October 2014, alongside partner organizations, AIDA called Inter-American Human Rights Commission’s attention to forced displacement caused by the inadequate implementation of mining and energy projects in Colombia. On that occasion, we asked the Commission to develop standards on displacement by megaprojects and urged the Colombian government to properly care for the victims. Megaprojects not only cause forced displacement, but also violate other human rights ranging from the loss of ways of life to the criminalization of social protest, as occurred in El Tule. In Mexico, the Miguel Augustín Pro Juárez Center for Human Rights published the report Han Destruido la Vida en Este Lugar (They’ve Destroyed Life in This Place, 2010), which documents the damage caused by megaprojects and by the exploitation of natural resources. According to the report, in addition to forced displacement, these projects cause harm to ways of life and broken cultural ties. I would add that displacements break community social networks, vital to the exercise of rights. Left with Questions What will happen to those whose land is expropriated by the Nicaragua Canal? Are they condemned to be displaced and see their dream of landownership destroyed? Who will guarantee respect for their human rights? In what way can Nicaraguan civil society and those unaffected by the project help them? Today the canal threatens to become a reality for one of the poorest countries in Latin America, with a recent history of dictatorship and civil war, that is each day more vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters. How do I explain do my son that to be a landowner will soon mean to be an employee? I still have no answer.

Read moreGreen Climate Fund Begins Accreditation Process

2015. This is the year. Sink or swim. It’s all or nothing. Opening the Green Climate Fund’s Ninth Meeting of the Board last month, Executive Director Hela Cheikhrouhou spoke with an urgency characteristic of the lead-up to December’s UN Climate Conference in Paris, describing this year as one of the last opportunities humanity has to change course and steer a sustainable path. As we approach the signing of a new global agreement on climate change, the efficacy of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) holds particular importance. Counting now with $10.2 billion, it will serve as the primary vehicle to finance projects designed to help all societies – whether developed or developing – confront the causes, and the effects, of a changing climate. At last month’s meeting, the Fund’s Board accredited its first intermediary and implementing institutions – charged with channeling money into developing nations – and then announced plans to begin allocating its resources before the year’s end. These accreditations, in turn signaling the imminent arrival of the first project proposals, represent an important milestone in the rigorous, nearly five-year process since the Fund was first established. "This will be the ultimate test of the effectiveness of the institution," said Andrea Rodríguez Osuna, AIDA’s Senior Attorney for Climate Change, who has been monitoring the development of the Fund. "When it all comes down to it, this is the step that matters." The first seven entities accredited by the Board represent a broad geographic and thematic range, and will likely be the first to submit proposals for funding. Including organizations from Senegal to Peru, they specialize in issues such as coastal protection, biodiversity conservation, sustainable development, and improving the lives of low-income communities. While the accreditations represent an advance towards the actualization of the Fund’s mission, a number of significant organizational decisions remain under debate, or are as yet unaddressed. Among other topics on the agenda last month, the Board addressed the expected role and impact of the Fund, which will enable them to identify financing priorities, and the Initial Investment Framework, which will outline what types of projects will be financed and how they will be selected and assessed. "Alongside accreditation, these elements are essential. Without them, the Fund can’t advance toward the future, toward having more focused and productive discussions," Rodríguez explained. The criteria and methodology for the Fund’s Initial Investment Framework triggered a heated debate, which largely pitted developed against developing nations. On one side, the developed nations pushed for minimum required benchmarks that would enable simpler measurement of success; on the other side, developing nations pushed for qualitative measures with no strict requirements that would better ensure more equal access to funds. Finally, they reached a compromise, deciding to use non-mandatory indicative minimum benchmarks that would both encourage ambition and take into account the needs of those developing countries most vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. The Secretariat will present the proposed benchmarks for further development in about a year’s time, at the 13th meeting of the Board. Discussing the expected role and impact of the Fund, the Board came to an uncharacteristically unified decision – to keep the Initial Investment Framework under review, and to take action as needed regarding the criterion on needs of the recipient countries. Agreeing the document presented by the Secretariat lacked sufficient information, the Board requested they be presented with more technical and scientific data before beginning to outline their priorities. Notably missing from the conversation, due to lack of time, was an item particularly important to AIDA’s work, Enhanced Direct Access, which would obligate public participation in certain projects. If approved, this direct access would ensure the moreequitable involvement of all the actors working to confront the effects of a changing climate. The next meeting of the Board of the Green Climate Fund will be July 6-9 at the Fund’s headquarters in Songdo, South Korea. AIDA will be there again to monitor these issues and report back on important developments, as the world prepares for a new global climate accord, and the Green Climate Fund moves ever closer to implementation.

Read more

Stopping Fracking: Together We’re Stronger!

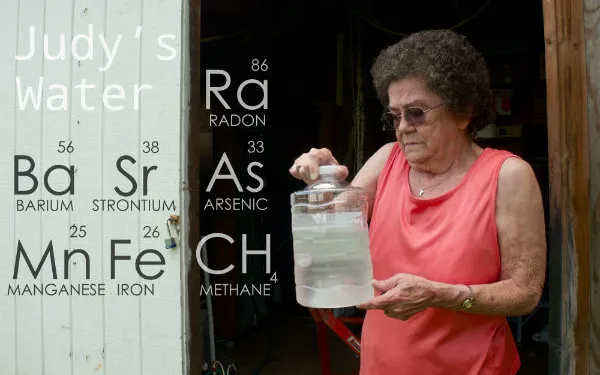

It’s an increasingly recognized reality: the world cannot burn its reserves of fossil fuels and expect the planet to be habitable. But energy companies continue extracting fossil fuels in pursuit of near-term profit, rather than adapting their business models for the sake of long-term sustainability. Already, much of the world’s reserves of easily extracted, high-quality fossil fuels have been exhausted. New horizontal drilling technology, combined with hydraulic fracturing (fracking), has made exploitation of hard-to-reach ("unconventional") oil and gas deposits possible. For a variety of reasons, fracking poses very high risks to public health and the environment. AIDA has begun working with civil society organizations and institutions to generate information, stimulate debate, and join forces to prevent the negative impacts of fracking in Latin America. The Risks of Fracking Fracking for unconventional deposits involves drilling into the ground vertically, to a depth below aquifers, and then horizontally through layers of shale rock. Then fracking fluid (a high-volume mixture of water, sand, and undisclosed chemicals) is injected at very high pressure to fracture the shale, thus releasing the oil and gas trapped inside. After fracking fluid surfaces, energy companies typically dump it into unlined ponds. The chemical soup—now also contaminated with heavy metals and even radioactive elements—seeps into aquifers and overflows into streams. The severe and irreversible damage associated with fracking includes: Exhaustion of freshwater supplies. Contamination of ground and surface waters. Air pollution from drill and pump rigs. Harms to the health of people (low birth weight, birth defects, increases in congenital heart defects, deformities, allergies, cancer, and respiratory disease) and other living things. Unregulated emissions of methane, which traps 25 times more heat than carbon dioxide. Earthquakes. Effects on subsistence activities, such as agriculture. For and Against Fracking Given these risks, France, Bulgaria, Ireland, and New York State have turned their backs on fracking, banning it or declaring a moratorium in their territories. In Latin America, however, many countries are opening their doors to fracking. Governments are doing so with little or no understanding of its impacts, and in the absence of an adequate process to inform, consult, or invite the participation of affected communities: Mexico promoted fracking through a landmark energy reform law in 2013. As of 2015, 20 wells have been drilled using this technique. Argentina has the largest number of fracking operations in the region, and the largest reserves of shale gas in America. As of 2014, there were more than 500 fracking wells in Neuquén, Chubut, and Rio Negro[6], including wells in the Auca Mahuida reserve and in Mapuche indigenous territories. In Chile, the state-owned oil company ENAP started fracking on the island of Tierra del Fuego in 2013. More drilling is planned in the coming years. Colombia and Brazil have opened public bidding and signed contracts with oil companies for exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbons through fracking. Bolivia's state-owned oil company signed an agreement in 2013 with its counterpart from Argentina to study the potential of fracking in Bolivia. Better together In October 2014, with the help of AIDA, the Regional Alliance on Fracking was formed to raise awareness, generate public debate, and prevent risks associated with the technique. The alliance seeks to ensure that the rights to life, public health, and a healthy environment are respected in Latin America. The idea for the alliance came from previous regional coordination initiatives promoted by Observatorio Petrolero Sur and the Heinrich Böll Foundation. The alliance currently consists of 33 civil society organizations and academic institutions from seven countries in the region. They are working together to: Identify fracking operations in the region, their impacts and affected communities, and promote civil society strategies to stop them. Organize workshops and virtual seminars on the impacts of fracking. Develop international advocacy strategies to stop fracking in the region. Conduct a regional outreach campaign on the issue. The alliance is strengthened by the expertise of its members, its regional scope, and the institutional support provided by organizations in each country. Given its collaborative nature, it is always open to the participation of new institutions and individuals interested in the subject. Major achievements Many civil society organizations, indigenous peoples, and institutions in the region have been working to stop fracking. They have developed strategies to generate information, raise awareness, promote public debate, and influence decision makers. Their achievements encourage us to improve coordination for greater impact throughout Latin America. Already, their efforts have resulted in: More than 30 municipal orders declaring a ban or moratorium on fracking in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Many have been based on the precautionary principle, as well as on concerns about surface and ground waters and public health. Judgments suspending contracts for fracking in Brazilian oil basins in Sao Paulo, Piauí, Bahia, and Paraná. Judges have also ordered Brazil’s National Petroleum Agency not to open further bidding until the environmental risks and impacts of fracking are sufficiently understood. Publications on the impacts of fracking, community awareness campaigns, and a bill – supported by more than 60 national deputies and nearly 20,000 people – to ban fracking in Mexico. Greater public awareness of fracking, and public debate, in Colombia and Bolivia. Through regional collaboration, AIDA will continue to make progress on preventing the impacts of fracking in our communities, and promote an energy future that is both renewable and humane.

Read moreBelo Monte: The Urgency of Effectively Protecting Human Rights

Four years ago this month, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights took an important step forward for the peoples of the Xingú River Basin. It requested that the Brazilian government adopt precautionary measures to prevent irreparable damage to the rights of indigenous communities along the Amazonian tributary. Their cultural integrity and way of life were, and still are, at risk from the construction of the world’s third-largest dam, Belo Monte. Yet that major victory for those fighting to protect life on the Xingú has been diluted with time. As the decision weakened, so too did confidence in the Commission, an organ of the Organization of American States (OAS) charged with ensuring the protection of human rights on the continent. The Initial Request In November 2010, AIDA and partner organizations in Brazil requested precautionary measures from the Commission in a context of gravity and urgency characterized by: An irregular licensing process. An insufficient Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA), which contained neither all possible impacts nor the mitigation measures needed to guarantee the communities’ rights, and was not translated into the indigenous languages of the affected populations. The project’s failure to comply with more than 60 social, environmental and indigenous provisions established in the previous license as safeguards for the rights of the affected. Absence of consultation with affected indigenous communities and lack of their free, prior and informed consent. In response, the Commission requested that Brazil immediately suspend construction and all licensing of the dam until the project complied with the following conditions: Undertake consultation processes that are of good faith and culturally appropriate, with the goal of achieving the free, prior, and informed consent of affected communities. Ensure that affected communities have access to the Environmental and Social Impact Statement in an understandable format, which includes translation into indigenous languages. Adopt measures to protect the cultural integrity and way of life of indigenous peoples, including those in voluntary isolation, and to prevent the spread of diseases and epidemics among affected communities. The Response of Brazil and the OAS The Brazilian Government rejected the measures, calling them "precipitous and unwarranted." In response, Brazil withdrew its envoy from the Commission and recalled its ambassador to the OAS. Then, claiming a need for economic austerity, Brazil suspended funding to the Commission and defaulted on its annual compulsory contribution to the OAS. The outlook worsened when the Secretary General of the OAS, José Miguel Insulza, told the BBC: "The Commission makes recommendations. They are never mandatory orders… no country will be violating a treaty if they don’t do what the Commission asks. The Commission has no such binding force." These undermining comments provided several hostile member States with justification for launching a process to "reform" the Inter-American Human Rights System. The controversial process lasted more than two years and, rather than strengthen the Commission, the hostile States actually attempted to undermine its autonomy and weaken its mechanisms. One Step Back On July 29, 2011, just four months after granting the precautionary measures, the Commission modified them. It withdrew its request for suspension of construction and licensing, claiming the fundamental argument had turned into a debate, which went beyond the scope of the precautionary measures, on whether prior consultation had been conducted with the indigenous communities and whether they had given their informed consent for the project. Instead, the Commission requested that Brazil adopt new measures to protect the way of life and personal and cultural integrity of indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation, as well as the health and territory of all affected indigenous communities. This change represented a major setback, not just for the indigenous communities of the Xingú, but also for the thousands of communities throughout the region whose cultural integrity and way of life are at risk from the heedless implementation of projects like Belo Monte. Brazil’s indigenous communities had hoped that the Commission would stand by its decision to suspend the dam, and would protect them while the case – presented in 2011 by AIDA and partner organizations from Brazil – was underway. Up Against Time After four years, Brazil has not only breached the precautionary measures, but has also repeatedly requested that they be lifted. Worse still, the government has allowed construction of the Belo Monte Dam to continue, and the project is now 70 percent complete. A few months ago, the company in charge of construction, Norte Energia S.A., requested the dam’s operating license from the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Natural Resources. Once granted the license, they will begin to fill the dam’s reservoir and, with it, flood a portion of the Amazon half the size of Rio de Janeiro. The Commission has yet to petition the Brazilian government to determine whether or not the project’s authorization included a process of prior consultation This important step remains despite the fact that, when modifying the precautionary measures, the Commission itself noted that the discussion had to happen in the context of a petition. What’s the risk? When the Commission finally makes a decision on the case it may be too late to prevent damages to affected communities. A Major Challenge Although there has been some progress in protecting affected communities as a direct result of the precautionary measures, which the Brazilian government has yet to recognize officially, the process thus far has clearly demonstrated that the Inter-American Human Rights System is imperfect and vulnerable to political pressure. This vulnerability must be overcome. We must focus on building a truly efficient System that works best for its beneficiaries: the victims of human rights abuses. Four years after what seemed like an important victory, Belo Monte has taught us that if we seek to protect human rights in the region effectively, governments must not be allowed to jeopardize the system established for that purpose through political and economic pressure. Due to the realities of the region, many cases like Belo Monte have come, and will continue to come, before the System. While they are not easy to resolve, we mustn’t choose inaction in the face of suffering. In the case of Belo Monte, the Commission still has time to act. It’s our hope that this case will become a model for equitable access to justice. At AIDA, we will continue working until we ensure that the environment and the rights of communities in Brazil’s Xingú River Basin are fully respected.

Read more

Toward a law to protect glaciers and water in Chile

More than 70 percent of the world’s fresh water is frozen in glaciers,[1] making these giants the most important freshwater reserves on the planet. The distribution of this wealth has been generous to some countries. According to the Randolph Inventory, the most complete map of glaciers in the world, Chile is the guardian of the largest area of glaciers in South America: 14,600 square miles distributed across thousands of glaciers that reach from the peaks of the Altiplano in the north to the extreme southern tip of the continent. The most dangerous threats to glaciers are climate change and industrial activities near them, especially mining. Through strategic litigation and advocacy, AIDA is working to halt the harms from both of these threats. Climate change has caused the decline of snow and rainfall, as well as an increase in temperature, which reduces the accumulation of ice and increases the melting of glaciers. Mining exploration and exploitation degrade glaciers with road construction, drilling, explosives, and toxic materials. These activities also generate dust that settles on glaciers, making them darker and accelerating their rate of melt. Although we know that water is fundamental for life, and that glaciers are dangerously threatened, surprising littleinternational law protects glaciers. No international treaty aims to preserve them, nor is any such treaty under consideration. At the national level, only Argentina has a law to protect its glaciers. In Chile, draft legislation to protect glaciers has been debated in Congress for many years. Bearing in mind the drought currently plaguing the country, what better reason could there be to develop a SMART legal tool to care for Chilean glaciers? In search of a law The first attempt to enact a law to protect Chile’s glaciers was in 2006. It was driven by the approval of the Pascua-Lama mining project, which threatened the mountainous glaciers in the north of the country. The unsuccessful initiative was shelved in 2007. On May 20, 2014 members of Congress, calling themselves "the Glacier Caucus," proposed a new law to preserve the glaciers. Mining and geothermal companies severely criticized their proposal, which forbade mining and other activities that harm glaciers. This March, the executive branch made a counterproposal. According to environmental organizations, the spirit of the Glacier Caucus law was completely changed in response to mining-industry demands. What follows are points for and against the government’s proposal, based on the minutes in (Spanish) of a collaborative meeting of environmental organizations: Positive Recognizes glaciers as freshwater reservoirs, as providers of ecosystem services, and as national public property. Prohibits applications for rights to harvest glacial water. Strengthens the power of the General Water Directorate to generate information, monitor the status of glaciers, and impose fines. Elevates the legal hierarchy of the glacier inventory. Negative Does not protect all glaciers, only those found in national parks or wildlife reserves. This is a serious oversight, considering that the most threatened glaciers are in the north, where national parks are rare and where they share territory with mining reserves. Worse, still, glaciers in the north supply drinking water to millions of people who live in areas where water is scarce. Could safeguard some glaciers outside of protected areas if the Committee of Ministers for Sustainability considers them "strategic water reserves." The proposal, however, makes no reference to the tools or public funds needed to make such an assessment. The risk is that this designation would eventually be left to consultants who frequently work for mining companies. Leaves glaciers that are not considered “strategic reserves” open to industrial projects, depending on the conclusions of Environmental Impact Assessments. In the past, EIAs have permitted such damaging projects as the Pacua-Lama, Andina 244, Los Bronces, and Los Pelambres mines. States that a project’s environmental permit will only be reviewed if the project currently impacts glaciers in national parks or those declared "strategic reserves." All other glaciers remain subject to the mining and energy projects that are already harming them. Internal debates in Congress will continue. We truly hope the resulting law will provide all glaciers with their due protection and that similar laws will be enacted in the rest of the countries where glaciers hold precious water for future generations. Meanwhile, AIDA’s dedicated legal advocates are working hard to prevent and minimize mining threats to the environment and people. AIDA is currently preparing a guide, Basic Guidelines for the Environmental Impact Assessment of Mining Projects: Recommended Terms of Reference (in Spanish), detailing the comprehensive analysis that must be completed for any proposed mining project. We are advocating with government agencies to conduct thorough assessments before approving new mine projects and, when necessary, we’re pursuing strategic litigation to compel agencies to improve their assessments. We’re also strengthening environmental laws and precedents that apply to extractive industries. In Colombia and Panama, AIDA is actively advocating revisions to the national mining codes, specifically to protect crucial water resources. Bringing international law to bear on the issue, we’re using international agreements to establish precedents that apply to mines broadly. We’ve also begun to create a pool of technical experts to help local communities and governments understand and evaluate proposals for mineral extraction. Please watch this blog for upcoming news about mines, water, and AIDA’s efforts to protect a healthy environment. [1] According to data from Global Water Partnership: http://www.gwp.org/

Read moreInternationally Advocating for Accountability for Human Rights Abuses

Juana[1] is suffering from respiratory problems and her sister has asthma. They live in La Oroya, a small city in Peru’s central Andes. It was years before Juana had access to the information she needed to understand the source of their illnesses: toxic contamination from the Doe Run metal smelter. Although there has been some progress, Juana and the rest of the people affected by the contaminated air in La Oroya still do not receive the specialized and comprehensive medical care they need. In cases like La Oroya, victims don’t always find justice in their own countries and must raise their demands to an international level. One space to do so is the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights public hearings, held twice a year in March and October. AIDA has actively participated in case hearings on specific human rights violations, such as in La Oroya. But we have also requested and received thematic hearings on problems facing Latin American countries or the region as a whole. We have participated alongside and in collaboration with other civil society organizations. "By providing information and arguments, we encourage the Commission to make visible worrisome situations of human rights violations caused by environmental degradation, and to take actions to stop them: develop standards, monitor cases, and make recommendations to States," explained María José Veramendi Villa, senior attorney at AIDA. Last October AIDA and partner organizations called the Commission’s attention to mining and energy projects that force displacement of people and communities in Colombia. We also requested that the Commission develop standards governing displacement caused by large infrastructure projects, and insisted that the Colombian government properly respond to the victims. "These hearings are the most comprehensive and flexible tool to ensure the Commission receives information about the issues that are troubling to the region. There are so many worries, and so many organizations wanting to be heard, that there is not enough time. The hearings are an indicator of the most relevant issues of the times and, through them, civil society develops an agenda of work," said Ana María Mondragón, attorney at AIDA. AIDA returned this month to Washington, D.C., seat of the Commission, to participate in a thematic hearing that brings to the table a current and deepening concern: the predominant role corporations are playing in the violation of human rights in Latin America. One example is the case of Máxima Acuña Chaupe in Cajamarca, Peru. The Yanacocha mining company is interested in developing a project on her territory and, in order to do so, accused her of usurping land. Although a judicial court ruling established Máxima’s innocence, she and her family live in fear that the company may again try to take away their home. The case of the Chaupe family, and many others in the region, demonstrates the importance of bringing this issue before the Commission. "During the hearing, we presented information to fuel debate about opportunities for the Commission to create, implement and strengthen international standards on business and human rights," explained Veramendi Villa. "By doing so, the Commission can urge States to control and/or sanction corporations – like Doe Run Peru and Yanacocha – whose activities harm the environment and violate human rights and ensure access to justice for its victims." [1] Name has been changed to protect confidentiality.

Read moreWetlands: Vital and At Risk

Temporarily or permanently flooded extensions of land create wetlands— oxygen-deprived, hybrid ecosystems that combine the characteristics of both aquatic and terrestrial systems. Wetlands include marshes, páramos, bogs, peatlands, swamps, mangroves and coral reefs. Wetlands provide people with a host of benefits: Wetlands are natural supermarkets that contain an incredible amount of biodiversity: they are home to more than 100,000 known freshwater species. Our allies in the fight against climate change, wetlands capture and store carbon from the atmosphere. It is estimated that over long periods of time, a hectare of mangroves captures 50 times more carbon dioxide than a tropical forest. Wetlands help to reduce the risk of natural disasters . An example of this happened in 2011, when the Veracruz Reef System in the Gulf of Mexico protected the city of Veracruz from the category four Hurricane Karl. Wetlands are a source of livelihood and employment for millions of people. In Panama alone, 90 percent of incomefrom fishing comes from catching species that, at some stage in their life, depend on the wetlands of the Panama Bay. What’s more, water to irrigate the country’s 570 million agricultural crops comes from these ecosystems. By forming beautiful landscapes, wetlands are a center of recreational and tourist activities, such as bird watching. Under threat Even though they are one of the most productive ecosystems in the world, more than 64% of the world’s wetlands have disappeared. The causes of their degradation include: Activities like agriculture that promote changes in land use , and contribute to the loss of coverage of wetlands. An example is the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta in Colombia, which is at risk from agricultural practices that have affected its water supply. Poorly planned urban development like that which threatened Panama Bay, where the mangroves were filled in and cut down to construct roads and houses. Obstruction of the water flow that feeds wetlands, as in the construction of the Las Cruces hydroelectric project in Mexico on the San Pedro Mezquital river, on which Marismas Nacionales, one of the most important mangrove forests in the country, depends. Contamination of subterranean water sources by activities like mining. What can we do for them? At AIDA we work to protect wetlands in the Americas . We’ve advocated for the preservation of the Colombian páramosand the Mexican wetlands, such as Cabo Pulmo, Marismas Nacionales and the Veracruz Reef System. We’ve also created rigorous reports about the international legal obligations that Costa Rica must meet to protect its corals, and about the standards of protection of corals in Mexico. And we’re ready to do more! We are currently preparing for the 12th Conference of Parties (COP12) for the Ramsar Convention , an intergovernmental treaty that has since 1971 promoted the protection of wetlands and established principles for their conservation and sustainable use through national action and international cooperation. The countries that sign and ratify the Convention are home to wetlands on the Ramsar List. They commit to taking steps necessary to maintain the ecological characteristics of these sites , which hold such significant value for their country and for all of humanity. The Conference will put to the test the promises that Latin American countries have made to protect their wetlands. The Parties will release Strategic Plan 2016-2021 , which will lay the foundation for the conservation of these ecosystems in the region. We’ll be at the Conference alongside partner organizations and decision markers to advocate for the best possible preservation of these beacons of health and biodiversity for the region.

Read morePáramos: Defending Water in Colombia

Colombia’s páramos occupy just 1.7 percent of the national territory, yet they produce 85 percent of its drinking water. These rich sources of life are threatened by activities like large-scale mining, and their protection should be a point of national interest. So just how does the magic happen? The páramos are high altitude wetlands. Despite being located in the equatorial zone, they remain cool throughout the year, which enables their soils to maintain rich volcanic nutrients. All these characteristics make the páramos true sponges that capture moisture from the atmosphere, purify water and regulate its flow. The growth of the economy, the production of electricity and life itself are all made possible by the water provided by Colombia’s páramos: Bogota’s water comes from the páramos of Sumpaz, Chingaza (at risk) and Cruz Verde (at risk from mining exploration). The water in Medellin arrives from the páramo of Belmira. The Santurbán páramo (at risk from gold mining projects) supplies water to Bucaramanga. In Cali, the Farallones are vital springs of water. Life in all these cities depends on the páramos. That’s why AIDA is committed to the protection of these valuable ecosystems. It’s about defending our sources of fresh water, our right to live. This fight recently called us to: Call the World Bank’s attention to the risks of its investment in the Angostura mine, in the Santurbán páramo, which would harm both people and the environment. Co-organize a seminar about páramos and mining at the Universidad Sergio Arboleda in order to discuss and understand the latest legal and technical regulations on the subject. We Are Not Alone Social movements in defense of water, life and páramos have blossomed across the country. The Committee for the Defense of Water and the Santurbán Páramo and the Committee for Cruz Verde are two strong examples. Greenpeace Colombia has also promoted the end of mining in the Pisba páramo in Boyacá. Meanwhile, after many extensions, the Environmental Minister announced last December the delimitation of the Santurbán páramo. However, he also announced that mining projects that already had a title and an environmental license would be permitted to continue. The Canadian mining company Eco Oro then issued a public statement that, even with the delimitation of Santurbán, it would continue developing the Angostura mine on a smaller scale. This delimitation opens the way for similar actions on which the recognition and protection of other Colombian páramos will depend. As members of civil society we must remain vigilant so that such actions comply with national and international environmental and human rights standards. Our water, and therefore our life, is at risk. Where will our fresh water come from in 2015, when our numbers are millions more? If we don’t protect our páramos today, Colombia’s future generations will be deprived of access to water. Current problems in Lima, Peru and São Paulo, Brazil remind us that this reality might not be too far away.

Read more

Four Recommendations for the Summit of the Americas

Inequality has increased in the last decades in Latin America, and this clearly is an obstacle for democracy. Latin America remains the region with the greatest income inequality on the planet. Considering this, the Organization of American States has made "Prosperity with Equity" the theme of its upcoming Summit of the Americas. In Panama on April 10 and 11, Heads of State and Government will pledge concerted actions at both the national and regional levels to confront the development challenges of the continent. I believe that the main goal should be to just stop doing certain things, or, at least, to act differently. When I asked Eli, an indigenous Ngobe from Panama, what she wanted from her government, she said, "Just that they leave us alone." Drawing on OAS consultations with civil society, AIDA analyzed two of the eight Mandates for Action, the document to be negotiated at the Summit. From this analysis, we have made the following recommendations relating to the mandates on energy and the environment: 1. Stop building large dams The Mandates establish that the region will join the United Nations Initiative, Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL). Since access to energy plays a key role in reducing inequality, we recommend working with this initiative provided hydroelectric dams are excluded from sustainable energy. Among other harms, Dams produce greenhouse gases, aggravating climate change, especially in tropical regions. Dams cause irreparable harms to the environment and human rights violations. Dams typically cost twice as much as their developers’ estimates, even without considering their socio-environmental damages. In addition, constructing these energy dinosaurs takes much more time than expected. Three currently suspended dams prove the point: Belo Monte (Brazil) - Suspended after protests of affected communities whose compensation had been breached. It is a year late, and the project is facing fines and the possible payment of additional interest on loans from Brazil’s national development bank, BNDES. El Quimbo (Colombia) - The filling of the dam is suspended by judicial order for lack of an evaluation of its impact on the fishing sector. Barro Blanco (Panama) - Suspended by an order of the government while they revise—and hopefully fix—irregularities in the Environmental Impact Assessment. From all this, we remind the Summit of the Americas that last December more than 200 organizations, networks, and movements from across the world requested that governments, international organizations, and financial institutions realize that large dams are an unsustainable source of energy and implement truly sustainable solutions. 2. Recognize the human rights impact from climate change Climate change has caused and will continue to cause serious impacts in Latin America that are compromising the enjoyment of human rights. Climate change is a priority on the Summit’s agenda, which is good. But government leaders should incorporate an understanding of the relationship between climate change and human rights. They should commit to respect human rights in all climate actions. The United Nations and the OAS General Assembly have recognized that the respect for and enjoyment of human rights are intrinsically connected to climate change. The World Bank has concluded that climate change complicates efforts to end poverty, which has clear implications on human rights. Even the recent draft of the negotiating text of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change contemplates the necessity to respect human rights. For all these reasons, the Summit should consider that the link between climate change and human rights must be incorporated into all actions seeking to combat inequality and promote better standards of living. 3. Include a commitment to mitigate climate change, not just adapt to it The Summit’s Mandates for Action refer to adaptation measures. But mitigation should not be left out. These actions would reflect the reality of the region, in which important efforts are being developed to confront climate change. Considering the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, all States must demonstrate willingness to implement mitigation actions to confront climate change. Although not all States should mitigate to the same extent, all countries should contribute to this task—including those in Latin America. 4. Recognize that corruption undermines equity, and include actions to eradicate it The Mandates for Action recognize the impacts of corruption in as much as the use of technology is intended to improve public participation. But corruption is a structural problem in the region and actions to confront it should be part of democratic governance. Corruption has a direct relationship with inequality, systematically preventing real progress in the fight against poverty.

Read more

5 Reasons to Donate to AIDA

We all must leave a legacy, my grandfather said. For him – beyond being loving husbands and wives, committed parents, responsible children, faithful friends and fulfilled workers – that means contributing something to the benefit of humankind. The wise words of my grandfather guide my professional life. In nine years of working with AIDA, I have had the great pleasure of seeing progress made on cases we’ve worked on throughout Latin America. These successes give me the energy to go the extra mile whenever necessary. Many times, however, I’ve felt the frustration of seeing so many people and places that need our help, and not having the financial or human resources to do so. If you agree that there is nothing more valuable than contributing to building a better world, and a more habitable place for future generations, then I have a suggestion for you: Please support AIDA’s work by making a donation! 5 Reasons to Support Our Work To enable you to make an informed decision, here are five reasons why supporting our work is an excellent idea: We are an international nonprofit organization with more than 15 years of experience in service to one fundamental mission: to use the law to protect the environment of the Americas, with a focus on Latin America. "Protecting our right to a healthy environment" is the motto that guides our actions. We are a group of Latin American attorneys who work with commitment. Our experience enables us to develop strategies before international bodies and organizations to ensure that the States comply with their environmental and human rights obligations. We work in partnership with national organizations, strengthening and complimenting their efforts. We firmly believe in public participation and capacity building to achieve greater impact and results over the long term. We share our knowledge with the partners and communities with whom we closely work. We take the great care when investing our funds. We work efficiently and effectively. We carefully select cases that will set a legal precedent and serve as an example for environmental defense in the countries of the region. Our work has a global impact, today and in the future. We work for the common good of all people: protecting vital resources like clean air and clean water. We consider our donors an integral part of our team. Without your contribution, it would not be possible for us to provide free legal assistance to communities fighting to defend their natural environment and protect their basic rights. With your support We will continue ensuring the protection of marine and coastal resources, the preservation of fresh water, effective responses to climate change, and the human right to a healthy environment. Helping us is simple and safe: You can do it right here! THANK YOU for believing in our work!

Read more