Blog

The importance of the “how” in the energy transition

Of the global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuels, one of the main causes of the climate crisis, nearly half come from coal use. Latin America is no stranger to the problem because it participates in both coal burning and the extraction of the mineral, which, after export, is used as a fossil fuel source in other parts of the world.In this context, the closure of coal-fired power plants—as is happening in Chile—is both great news and an opportunity to steer the energy transition toward justice.But in a just energy transition, the "how" matters: every step toward defossilization must ensure energy systems based on non-conventional renewable sources, respect for the environment and human rights, and responsible closure and exit processes. Thus, the Chilean case, which we explain below, is an important example of why the region needs to implement responsible decarbonization. When decarbonization causes more pollutionIn early 2024, AES Andes SA closed the Norgener thermoelectric power plant in Tocopilla, a coastal city in northern Chile. As part of the closure process, the company rapidly burned the 94,000 tons of coal it had stored at the plant, affecting a city already saturated with pollution and publicly recognized as an environmental sacrifice zone.The population of Tocopilla was exposed to potential health effects, including impacts on the respiratory system, increased risk of heart attacks, and—in children—perinatal disorders, developmental disorders, and impaired lung function, among others.The forced burning of coal was authorized by the National Electricity Coordinator (CNE)—the agency responsible for managing the various energy sources that enter the national electricity system—and displaced the use of renewable energy. To stop the burning, AIDA, Greenpeace, and Chile Sustentable, together with local communities, filed an appeal with the Santiago Court of Appeals to halt it, but the court's decision came after the coal had already been burned. Furthermore, the court ruled that the case should be reviewed by a specialized court in a more lengthy proceeding. A bad precedent for Chile and for the continentBy authorizing the burning of the remaining coal from the Norgener thermoelectric plant, the National Electricity Coordinator made an exception to the law governing the order of energy dispatch. Shortly thereafter, in September 2024, the agency issued an internal procedure to order the early closure of power plants. Although it is an attempt to streamline the closure process, the measure opens the door for other companies with coal-fired power plants in the process of closing to replicate what happened at Norgener: burn their remaining coal under the argument of “emptying stock” and generate energy that enters the national electricity system with priority, once again displacing energy from renewable sources. In Chile, the National Electricity Coordinator decides which unit dispatches its energy to the system at any given time based on a criterion of increasing economic merit, according to which the energy with the lowest variable cost enters first. However, the internal procedure stipulates—without sufficient regulatory backing—that the agency may authorize dispatching energy outside economic order so that coal-fired power plants consume their remaining fuel before closing. In response, AIDA, Greenpeace, Chile Sustentable, and MUZOSARE (Women in Sacrifice Zones in Resistance) filed a complaint on February 6, 2026, with the Superintendency of Electricity and Fuels against the Coordinator and his advisors for approving and implementing the measure. The complaint represents an opportunity to do things right: for the sector's regulatory body to ensure that the planning for the closure of thermoelectric power plants does not end up rewarding poor coal inventory management at the expense of communities' health and a just energy transition. What the energy transition needsIn 2019, the Chilean government committed to closing all coal-fired power plants in the country by 2040. Since that public announcement, the timeline has been accelerated. But the urgency of decarbonization should not be used to favor companies operating thermoelectric plants or to harm communities near polluting industries. Doing so weakens Chile's climate leadership and sets a bad example for any decarbonization process in the region. In a just energy transition, companies along the entire coal and other fossil fuel supply chain have an obligation to ensure the responsible closure and exit of their operations. The energy transition is not merely a change in technologies; it is an opportunity to rethink energy and development models and to correct injustices. This requires clear and appropriate rules that promote energy system security, competition, and a healthy environment.

Read more

5 key facts about “rare” earth elements

In recent weeks, you have probably read or heard the term "rare" earth elementsContrary to what their name suggests, they are more common in everyday life than you might think. In fact, many of the technological innovations we use daily would not be possible without them.So why are they being talked about so much right now?Because today, "rare" earth elements and other minerals considered "critical" are at the center of disputes over their control, given their usefulness in the manufacture of technologies for the energy transition and for the military industry.But aside from the geopolitical tensions surrounding the issue, there are basic questions that arise when we hear this term, which is why we answer them here.By understanding where the raw materials behind the technologies we use come from, we can also rethink the kind of future we want. What are "rare" earth elements?There are 17 metallic elements, similar in their geochemical properties, used in many of today's technologies, from cell phones to electric cars.They include the 15 lanthanides of the periodic table of chemical elements—lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium, promethium, samarium, europium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, and lutetium—as well as scandium and yttrium.Promethium is usually excluded from this group because under normal conditions its half-life is short. Are they really rare?Contrary to what one might think, they are not "rare" in abundance, but rather in concentration. In other words, deposits with high concentrations are rare, making their exploitation and processing difficult. As a result, most of the world's supply comes from a few sources.But when they were discovered (in the 18th and 19th centuries), they were less well known than other elements. The most abundant "rare" earth elements are similar in concentration in the Earth's crust to common industrial metals (chromium, nickel, copper, zinc, molybdenum, tin, tungsten, or lead). Even the two least abundant rare earth elements (thulium and lutetium) are almost 200 times more common than gold. What are "rare" earth elements used for?They have unusual fluorescent, magnetic, and conductive properties, making them attractive for a wide range of applications.They are present in everyday objects such as smartphones, screens, and LED lights.In renewable energy, they are used to manufacture wind turbines and electric cars.Its most specialized uses include medical devices and military weapons. Where are they?They exist in various parts of the world, but just because a country has reserves does not mean that it exploits them. The countries with the largest reserves are:China: 44 million tons.Brazil: 21 million tons.India: 6.9 million tons.Australia: 5.7 million tons.Russia: 3.8 million tons.Vietnam: 3.5 million tons.United States: 1.9 million tons.Greenland: 1.5 million tons.In Latin America, besides Brazil, other countries where "rare" earth elements have been identified are Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru. Why is there so much talk about them now?The energy transition is intensifying competition for access to raw materials—including rare earth elements—needed for renewable energy technologies.To promote and facilitate access to these and other resources, some countries and international organizations refer to them as "critical."But they are not only important for renewable energy. "Rare" earth elements are also key to the military industry.Because global supply is concentrated in a few sources, there is growing interest among some countries in the Global North in controlling access to these resources. What are the impacts of their exploitation?The extraction of "rare" earth elements is mainly carried out in open-pit mines, which have serious environmental and social impacts:Water, air, and soil pollution.Heavy use of water and toxic chemicals.Radioactive waste.Loss of biodiversity.Health risks.Forced displacement of communities.Increased risk of economic inequality. "Rare" earth elements and other minerals considered "critical" are at the center of current debates over who controls their exploitation and production.As these are natural resources, often found in indigenous territories and critical ecosystems, a more urgent discussion is what kind of progress we want: one that encourages the excessive exploitation of resources, or one that respects the environment and people? If you would like to learn more about this topic, here are the links to the sources we consulted: USGS, Rare Earths Statistics and Information: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/rare-earths-statistics-and-inform… USGS, "Fact Sheet: Rare Earth Elements-Critical Resources for High Technology": https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2002/fs087-02/ Science History Institute, History and Future of Rare Earth Elements: https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/classroom-activities/role-playing-games/case-of-rare-earth… USGS, "The Rare Earth Elements-Vital to Modern Technologies and Lifestyles": https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2014/3078/pdf/fs2014-3078.pdf Institute for Environmental Research and Education, "What Impacts Does Mining Rare Earth Elements Have?": https://iere.org/what-impact-does-mining-rare-earth-elements-have/#environmental_impact_studiesLatin America’s opportunity in critical mineralsfor the clean energy transition: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/latin-americas-opportunity-in-critical-minerals-for-the-clean-ener…U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2025 : https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025-rare-earths.pdf pg 145

Read more

What comes next after the High Seas Treaty enters into force?

The day finally arrived. On January 17, the High Seas Treaty—officially known as the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement)—came into force, thereby becoming international law. A historic milestone that took more than two decades to achieve, the treaty establishes for the first time a legal framework to protect biodiversity in the high seas—whose waters cover almost half the planet and belong to all countries—and to ensure that the benefits derived from its resources are distributed equitably worldwide. The implementation of the treaty was activated on September 19, 2025, upon reaching its sixtieth ratification. As of January 15, this year, 83 countries are already States Parties to the agreement. Ratification means that countries, in addition to signing the treaty, give their formal consent to it, often by ensuring that their national laws are consistent with it.But what comes next with the entry into force of the High Seas Treaty? Legal obligations for States With its entry into force, the States Parties to the agreement must begin to comply with a series of legal obligations contained therein. Although some depend on the functioning of the treaty's bodies and mechanisms, others are applicable immediately, including the following:Publicly notify any planned activities under its control that may affect biodiversity in the high seas or on the seabed. These activities must follow the environmental impact assessment processes established by the treaty.Promote the agreement's goals when participating in decision-making forums with other international organizations, such as those that regulate maritime shipping, fishing, and deep-sea mining.Notify and report on matters related to compliance with requirements concerning marine genetic resources, sharing of non-monetary benefits, and cooperation for technology transfer and capacity building. Regarding the last point, the treaty establishes a Clearing-House Mechanism (CHM), a source of knowledge that many countries—especially developing ones—would not otherwise have access to. In general terms, the implementation of the agreement will include, among its most visible obligations, issues of cooperation and coordination between countries based on mechanisms established by the agreement and through links with existing international legal instruments that have historically been applied in isolation. Proposals for marine protected areas on the high seas One of the main goals of the treaty is the creation and proper management of marine protected areas (MPAs) on the high seas to conserve and restore the rich biodiversity found in the ocean.With the treaty now in force, this task cannot begin immediately because its implementation requires the functioning of specific bodies and mechanisms, including the treaty Secretariat, which will receive MPA proposals, and the Scientific and Technical Body, which will evaluate them and issue recommendations on their adoption to the Conference of the Parties.However, countries can begin now with the broad consultation process stipulated in the treaty to develop proposals for MPAs or other area-based management tools (ABMTs), which must be based on the best available scientific and traditional knowledge.Although it is up to countries to propose and then decide on the establishment of areas to be declared reserves for protection on the high seas, there are efforts from civil society to advance this issue. For example, the High Seas Alliance—a coalition of organizations in which AIDA serves as regional coordinator for Latin America—has preliminarily identified eight MPA proposals of high environmental value: three are in the Atlantic (Lost City, Sargasso Sea, and Walvis Ridge), four in the Pacific (Thermal Dome, Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges, Emperor Seamounts, and South Tasman Sea), and one in the Indian Ocean (Saya de Malha).The alliance is supporting the governments of Costa Rica and Chile in developing proposals for MPAs located in international waters adjacent to Latin America—the Thermal Dome and Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges. The first decision-making meeting of the agreement No later than one year after the High Seas Treaty enters into force—that is, at the end of 2026 or the beginning of 2027—its first Conference of the Parties (COP1) will take place, where key aspects for its implementation and the realization of its benefits will be decided.Only countries that have ratified the agreement may participate in decision-making; the rest may do so as observers. Countries that have only signed the treaty have a good-faith obligation to refrain from acts that defeat its purpose.Ahead of COP1, meetings of the Preparatory Commission are being held to develop proposals on the treaty's institutional architecture (its bodies and decision-making processes), which will be presented for adoption at the conference. With this historic milestone, another key phase now begins: implementation, which will translate it into concrete and lasting measures for the health of the ocean. Its impact will depend on how it is collectively applied and respected. And its effectiveness will be greater when all countries join the agreement.

Read more

10 environmental news stories to end 2025 on a hopeful note

We are nearing the end of a complex year, and taking stock seems daunting. Multilateralism is faltering as environmental crises worsen and urgently demand decisive action.In such turbulent times, it is worth taking stock of what we, as humanity, have achieved in building a more just and sustainable world for all who inhabit it.2025 will be remembered as the year when an underwater expedition thrilled us in real time, when we celebrated the implementation of agreements to protect life in the ocean, and when international court rulings transformed the pursuit of justice to protect people and the environment from the climate emergency.These are some of the environmental victories that this year has left us with, and they deserve to be celebrated, just as we honor the fire that shines in the darkness. Because even with small lights, we can continue to illuminate a path of hope toward environmental and climate justice. 1. International courts issued landmark decisions for climate justiceThe Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the International Court of Justice released their respective advisory opinions on the climate emergency. Both decisions clarified the obligations of states to protect the rights of people and nature in the face of the climate crisis.These decisions are part of an unprecedented global movement for climate justice, which also includes the advisory opinion issued in 2024 by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and similar future decisions, such as the one expected from the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights.Learn More: Dialogue Earth 2. Climate litigation exceeded 3,000 cases worldwideClimate litigation reached 3,099 cases worldwide, according to a report by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law and the United Nations Environment Program. Although climate litigation in countries in the global south is still in the minority (9.8% of the total documented), it has grown steadily. Brazil stands out as the third country with the most cases in the world (135), and other Latin American countries (Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, and Chile) are among the top 15 with the most cases reported.This growth demonstrates the increasing use of strategic litigation to promote concrete action on the causes and consequences of the climate crisis.Learn More: Sabin Center for Climate Change Law 3. Colombia declared its part of the Amazon free from oil and large-scale mining activitiesDuring the 30th UN Climate Change Conference (COP30), Colombia declared the entire Colombian Amazon region a zone free from oil and large-scale mining activities, announcing it as a "reserve zone for renewable natural resources."The decision implies an unprecedented limitation on the expansion of mining and hydrocarbon activities in more than 48 million hectares, equivalent to 7% of the entire Amazon region. It is also a call to other Amazonian countries to follow suit.Learn More: InfoAmazonia 4. Countries create a global mechanism to promote a just energy transitionAn important step forward at COP30 was the adoption of the Belém Action Mechanism, created within the framework of the Just Transition Work Program.The mechanism will function as a coordinating space to centralize global initiatives, offer technical assistance, and strengthen international cooperation. It is an achievement driven by civil society to promote ambitious climate action and a transition that does not repeat the mistakes of the fossil fuel era.Learn More: AIDA and The Climate Reality Project América Latina 5. An underwater expedition in Argentina marked a scientific and technological milestoneThe expedition "Underwater Odel Plata Canyon: Talud Continental IV," led by scientists from Argentina's National Scientific and Technical Research Council, in collaboration with the Schmidt Ocean Institute, explored the deep ocean in the Mar del Plata submarine canyon for 21 days, while broadcasting live on YouTube and Twitch.The result: 40 new marine species and an unexpected diversity of cold-water corals were discovered, findings that were seen and celebrated in real time by millions of people.Learn More: CONICET 6. The High Seas Treaty will finally enter into forceIn a process that took more than two decades, the High Seas Treaty this year reached the 60 ratifications needed to trigger its entry into force, which will occur on January 17, 2026. This binding agreement allows for the protection of the part of the ocean outside of national boundaries, almost half of the planet, through the creation of marine protected areas in international waters and the conduct of environmental impact assessments of planned human activities on the high seas. This is a historic milestone for the protection of the ocean and the well-being of millions of people in Latin America and around the world.Learn More: AIDA 7. Implementation begins on agreement ending harmful fisheries subsidiesThe World Trade Organization's Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies came into force in September this year. It is the first multilateral trade treaty to prioritize environmental sustainability, as well as a milestone in ensuring food security and the livelihoods of coastal communities.The agreement prohibits government subsidies that promote illegal fishing and the depletion of overexploited stocks.Learn More: WTO 8. Green sea turtles are no longer considered an endangered speciesAfter decades of decline, the population of green sea turtles is recovering. The International Union for Conservation of Nature no longer considers them endangered and has reclassified them as a "species of least concern."This sea turtle population has increased thanks to decades of conservation work to protect nesting areas, reduce capture, and prevent bycatch. AIDA was part of these efforts, protecting them in the 1990s from hunting—which was legal at the time—in Costa Rica.Learn More: AIDA and IUCN Red List 9. Protection of key ecosystems around the world, including the Galapagos, is growingUNESCO added 26 new biosphere reserves in 21 countries, the highest number in 20 years, and approved the expansion of 60,000 square kilometers in the Galapagos Biosphere Reserve in Ecuador to incorporate the Hermandad Marine Reserve. This will protect the area where dozens of marine species, many of them protected, transit, and which is considered one of the most diverse ocean corridors in the world.Learn More: LaderaSur and Government of Ecuador 10. Deforestation decreased in Afro-descendant territories in Latin AmericaAfro-descendant communities in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Suriname have significantly reduced their deforestation rates, according to new research from Conservation International.The study showed that Afro-descendant communities are critical to environmental conservation, as 56% of their lands are located in the 5% of the world with the highest biodiversity.Learn More: Conservation International

Read more

Our Contribution to Environmental Justice in 2025

At AIDA, one of our core pillars is using the law strategically — backed by science and international advocacy — to set important precedents that protect the environment and human rights across Latin America.This year, our work helped strengthen both regional and global legal frameworks so they can better respond to the social and environmental challenges we face today.These advances led to the creation of key legal tools that open new opportunities to defend communities and their territories, protect the region’s biodiversity, and hold governments and companies accountable.The progress we saw in 2025 highlights the transformative power of law, science, and the collective strength of communities when they work together. 1. Two new global treaties restore hope for the ocean — and for all of usThis year brought two historic achievements that could change the future of the ocean, and our own.The first is the ratification of the High Seas Treaty, which will take effect in January 2026. This legally binding agreement creates shared rules and a system of multilateral governance for the ocean areas beyond national jurisdiction — nearly half the planet.The second milestone is the entry into force of the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies. For the first time, a multilateral trade treaty puts environmental sustainability front and center by banning government subsidies that fuel illegal fishing and the depletion of overfished stocks.AIDA played an important role in ensuring Latin America’s perspectives were reflected in both agreements. We provided technical support to government representatives throughout the process, and we continue working to make sure these treaties lead to real, effective action across the region.Learn More 2. Maya community in Guatemala achieves a landmark environmental victoryIn Chinautla, Guatemala, the Poqomam Maya community won an unprecedented court ruling over decades of river pollution that violated their rights. The court ordered the municipality to carry out studies, programs, and plans to reduce pollution — and to ensure the community is involved every step of the way.This is the first time a court in Guatemala has recognized both a people’s right to a healthy environment and their central role in finding solutions. The ruling could inspire other municipalities along the Motagua River, the country’s longest river, where pollution also threatens the Mesoamerican Reef.Beyond providing legal support, AIDA helped the community document illegal dumping that harmed their water sources. This hands-on “community science” effort played a crucial role in both the lawsuit and the historic ruling.Learn More 3. Corte Interamericana marca un antes y después para la justicia climáticaOn July 3, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its long-awaited Advisory Opinion 32 on human rights and the climate emergency — a landmark moment for climate justice both regionally and globally. The Court clarifies the legal obligations of states to protect people and communities affected by the climate crisis, opening new pathways for justice in national and international courts, climate negotiations, and public policy advocacy.For the first time, the Court recognized the right to a healthy climate and affirmed that states have a duty to prevent companies from violating human rights in the context of climate change.Ahead of this decision, AIDA helped amplify the voices of communities across the region, facilitating their testimony before the Court and presenting our own arguments for recognizing the right to a stable and safe climate.Learn More Discover the stories behind these victories and our full review of the year in our 2025 Annual Report.

Read more

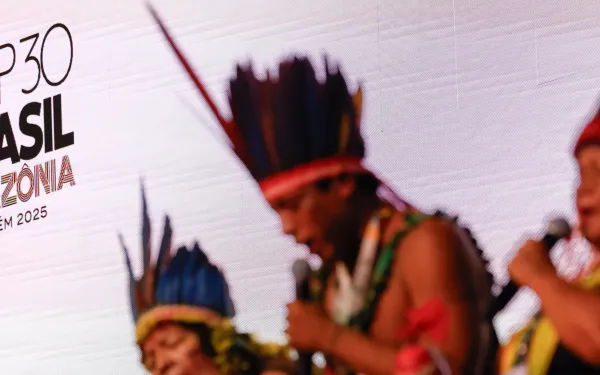

COP30 ends — with a few achievements to move forward

With more than 25 hours of delay, the 30th UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) has come to an end. The so-called "Amazon COP," held in the Brazilian city of Belém do Pará, leaves behind disappointment for failing to change course, but also some advances that can help push climate action forward. It was not a total failure: multilateralism remains intact, though battered.COP30 was marked by the presence of Indigenous peoples, especially from the Amazon basin, who filled the streets and side events. However, according to reports, only a fraction of these delegations gained access to the formal negotiation rooms, while a disproportionate number of representatives from the fossil fuel industry participated in the official event. This imbalance reflects the democratic health of the climate regime: at the Amazon COP, the power of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples was felt in the streets, but their voices remained underrepresented in decision-making spaces.A few days into the conference, the latest synthesis report of updated nationally determined contributions was released. Its message was more bitter than sweet, but it offered one important takeaway: although the gap to keep global warming below 1.5°C remains enormous and complex, the report confirms that the Paris Agreement has indeed helped steer the challenge. We are in a better position than in a scenario without the agreement: projected emissions growth has been slowed, though not nearly enough.At this point, it is clear that COPs will not "save the world," but it also seems impossible to overcome this crisis without the cooperative platform they provide. From that perspective, it is worth asking what COP30 leaves us. The approved agreement: Global MutirãoThe word "Mutirão" references the spirit of collective effort—body and soul—that Brazil sought to bring to the international negotiation process at this COP.The approved agreement reiterates the goal of keeping the planet’s temperature increase below 1.5°C, acknowledging that time is running out. To that end, it proposes two voluntary mechanisms, led by the Presidency, which for now seem more like statements of good intent than tools with teeth: a "Global Implementation Accelerator" and the "Belém Mission for 1.5°C."On financing, the text establishes a two-year work program on Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which concerns the public resources developed countries must provide, understood in the context of Article 9 as a whole.A footnote was added to clarify that this does not prejudge the implementation of the new global goal. Civil society organizations warn that this formulation risks further diluting developed countries’ specific obligations under the narrative of "all sources of financing," without clear rules on who must actually provide the resources and under what conditions. The real value of all this remains to be seen in practice. What was gained: A new mechanism for a just transitionA major achievement of COP30 was the adoption of the Belém Action Mechanism (BAM), a new institutional arrangement under the Just Transition Work Programme. It was the main banner carried by organized civil society.The mechanism is designed as a hub to centralize and coordinate just transition initiatives around the world, providing technical assistance and international cooperation to ensure the transition does not repeat the mistakes of the fossil era.The text incorporates many of the principles championed by Latin American civil society—including human rights, environmental and labor protections, free, prior and informed consent, and the inclusion of marginalized groups—as essential elements for achieving ambitious climate action.Even with gaps in safeguards and governance definitions, the BAM is a concrete step forward for this COP on climate justice. It creates a starting point to discuss not only whether there will be a transition, but how it will be done and under what rules, so as not to replicate the logic of the fossil economy. Its design and implementation will be debated at upcoming COPs, where it will be crucial for the region to arrive with solid, united proposals. Ending fossil fuels and deforestation: Two “almosts” that move us forwardAn agreement to leave behind fossil fuels and end deforestation—directly addressing the main drivers of the climate crisis—"almost" made it into the final decision.More than 80 countries from both the global north and south called for a roadmap to exit oil, gas, and coal. More than 90 supported a roadmap to stop and reverse deforestation by 2030. Although these requests made their way into drafts of the closing decision, they disappeared from the final text after resistance from major fossil fuel producers.Still, we do not leave empty-handed: Brazil, as COP30 Presidency, announced it will advance these roadmaps outside the formal framework of the UNFCCC. For the fossil fuel phaseout, Colombia committed to co-organize, with the Netherlands, the first global conference on the topic in April 2026.Although these items were not secured within the official negotiations, it is worth celebrating that—for the first time—such a broad coalition of countries united to achieve them. These two "almosts" matter: they set a new political and legal baseline for the rounds ahead. Two tools to advance adaptationCOP30 delivered tools to keep adaptation negotiations moving forward.The Mutirão decision calls for tripling collective adaptation finance by 2035, tied to the $300 billion USD per year agreed under the new global goal. This falls short of what the poorest countries asked for (tripling by 2030, with an explicit figure) and lacks clarity or guarantees regarding the role of developed countries. But it is a political anchor worth building on.At the same time, a first package of 59 indicators was adopted for the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). Several African countries and experts described them as "unclear, impossible to measure, and in many cases unusable," because they sacrifice precision and grounding in community realities in order to unblock the agreement. In response, the text included the "Belém–Addis Vision," a two-year window to correct flaws and make the framework operational by 2027.In short, we have more promises of money and an indicator framework weaker than necessary, but also a process through which the region can continue pushing for a useful GGA and for fair, sufficient adaptation finance. Loss and damage: Slow and uncertainProgress on this issue has been painfully slow compared with the urgency of the problem. At COP30, the third review of the Warsaw International Mechanism was finally approved. The result is frustrating: discussions have taken a decade while communities are already paying the cost of warming.On the other hand, the Loss and Damage Response Fund, created two years ago, issued its first call for proposals, with an initial package of $250 million USD in grants available over the next six months. The Fund has $790 million USD pledged, but only $397 million USD actually deposited—an enormous gap compared to the hundreds of billions estimated annually for developing countries.The expected political pressure for developed countries to scale up contributions was largely diluted in the final text, although the Fund was at least linked to the new global financing goal agreed at COP29. A new Gender Action PlanCOP30 concluded with the adoption of a new Gender Action Plan under the renewed Lima Work Programme. The Plan identifies five priority areas: capacity-building and knowledge; women’s participation and leadership; coherence among processes; gender-responsive implementation and means of implementation; and monitoring and reporting. It also provides a roadmap to ensure climate action is truly gender-responsive, with indicators to track progress. Methane: A super-pollutant still lacking the spotlight science demandsAt COP30, short-lived climate pollutants—especially methane—gained visibility thanks to a dedicated pavilion and dialogues with regional and global actors. The Global Methane Status Report 2025 was also presented, noting “significant” progress since the 2021 launch of the Global Methane Pledge. However, it warns that current progress remains far from the goal of reducing methane emissions by 30% by 2030.In the official negotiations, the draft of the Sharm el-Sheikh Mitigation Ambition and Implementation Work Programme included an explicit reference to methane mitigation through proper waste management, but that mention was removed from the final text, leaving only a general call to improve waste management and diminishing the focus on the urgent need to reduce emissions of a pollutant whose mitigation is essential to achieving the Paris Agreement goals. Still, during COP30, the global “No Organic Waste (NOW) Plan to Accelerate Solutions” was launched, aiming to reduce methane emissions from organic waste by 30% by 2030.Overall, this COP missed a crucial opportunity to advance its core objective. If we truly want to stay on track with the Paris Agreement, we must treat methane as what it is: a decisive opportunity we are still not seizing. How we close COP30 and prepare for the nextCOP31 will be held in Turkey, under the presidency of Australia. And despite the shortcomings of COP30, there are at least four things to defend and build on:The normalization of the debate on phasing out fossil fuels, with more than 80 countries openly calling for a roadmap and Colombia–Netherlands taking that discussion to a dedicated conference in 2026.A forest agenda that, although left out of the text, carries the promise of a Brazilian roadmap and explicit support from a wide group of countries.A small but real advance on adaptation, with the decision to triple finance and a first set of indicators that, while weak, offer a basis to push for improvements.The creation of a new mechanism for a just transition, which can shape how the transition unfolds—bringing together and strengthening efforts that support and protect workers, communities, and Indigenous peoples.

Read more

The home stretch of COP30: Shadows, contradictions, and some glimmers of hope

The first week is over, and the political phase of the 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) has begun in Belém do Pará, Brazil. These are the days when decisions must be made.A COP had not been held in a country where public protest is possible since 2021 — and people have certainly made their voices heard. On Saturday, a massive demonstration took place: thousands demanded climate justice in the streets, to the rhythm of Amazonian drums. There was also a theatrical "funeral for fossil fuels," reminiscent of Tim Burton, with monsters and somber widows bidding farewell to an era that must be buried.But it has not all been carnival. Indigenous leaders blocked access to the event several times and even entered the "blue zone" — the restricted area — en masse, denouncing the exploitation of their territories. Their discontent is absolute. Although COP authorities met with the group, they soon sent a letter to the Brazilian government requesting increased security and the dispersal of protests. Human rights and environmental organizations have warned about the risks of criminalizing protest and the harmful message this sends about the role of Indigenous peoples.These protests reflect communities that ended up being a minority in an event that promised to be inclusive. There was also widespread criticism of the disproportionately large number of fossil fuel industry representatives involved in negotiations — a dynamic that makes the path toward climate justice even more complicated.Finally, advisory opinions (AOs) must not be left out of this review. While not formally on the agenda, they have made a strong impact. Their central message is powerful: international cooperation is not optional — it is a legal obligation. It is no surprise, then, that the theme keeps resurfacing: in side events, in constant references by civil society and some national delegations, and in cross-cutting mentions across debates on finance, adaptation, and transition. The AOs are not merely being cited; they are being embraced. Momentum is building to fully unleash their potential at this COP and beyond. Negotiations: Four key issues in “presidential consultations”The COP Presidency acted quickly with a novel approach: to adopt the agenda without delays, it set aside four complex issues and moved them into “presidential consultations.”Article 9.1 — Public Funding from Developed Countries. The debate centers on whether climate financing should come only from public sources or also from private sources, as well as on accountability and reporting standards. Developed nations — which are legally obligated to provide this financing — are resisting, while vulnerable countries urgently need the funds to survive the climate crisis.Unilateral Climate-Related Trade Measures. These include policies such as carbon border taxes. They are considered unfair or protectionist, especially by Global South countries with less capacity to reduce emissions. Negotiations aim to prevent arbitrary trade barriers while respecting climate action.NDCs and Ambition. According to the latest NDC synthesis report, there is a significant gap between current commitments and what is required to stay below 1.5°C. Many negotiators argue that agreeing on concrete measures to close that gap is essential, but large emitters continue to resist.Synthesis of Climate Transparency Reports. Under the Paris Agreement’s Enhanced Transparency Framework, countries must periodically report emissions, actions taken, and financial support provided or received. At COP30, the debate centers on how to make these synthesis reports more robust, comprehensive, and useful. The consultations have been tense and slow. On Sunday, the Presidency published a "summary note" outlining possible pathways, and today a draft decision was released, though reactions are still forthcoming. In the coming days, closed-door sessions will continue and could lead to various outcomes. Based on the draft, it seems increasingly likely that COP30 will end with a “cover decision” consolidating all progress and addressing these complex matters. The final scope will depend heavily on what happens during the next four days. A just energy transition: Promises and a mechanism that worksThe Belém Action Mechanism for a Just Transition is a new institutional arrangement under the UNFCCC, championed by NGOs and Global South countries. Its objective is to bring order to the currently fragmented landscape of just transition efforts. The mechanism would coordinate initiatives, systematize knowledge, and provide quality financing and support — essentially evolving the Just Transition Work Program discussed since COP27.Civil society, particularly the Climate Action Network (CAN), has invested enormous effort in developing a strong decision that advances the creation of this mechanism. The G77 + China — the largest negotiating bloc of developing countries — supported this proposal, earning CAN’s "Ray of Light" award, given to actors making significant contributions to climate justice.Some developed countries presented less ambitious proposals, but even that confirms that convergence is drawing closer. Civil society remains optimistic that a concrete, positive outcome will be achieved — and ready to celebrate it. A path to phase out fossil fuelsThis story began in 2023 at COP28 in Dubai, when, for the first time, the idea of phasing out fossil fuels appeared in an official COP text.Now, at the opening of COP30, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva explicitly referenced a "route" for the energy transition, while Environment Minister Marina Silva has worked to reinforce the political momentum. Meanwhile, Colombia issued a declaration referencing the advisory opinions and seeking international support for the initiative. Several industrialized countries have revived their position through the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance.Today, 63 countries support a commitment to "Transition Away from Fossil Fuels." However, this is not yet part of the formal negotiation agenda — initiatives remain fragmented, and efforts proceed in parallel. What could emerge is a concrete action plan, a dedicated section in the final decision, or perhaps a roadmap for a future roadmap. The alternative is that it remains a voluntary coalition of willing countries pushing the idea forward. Climate finance: The central — and most complicated — issueFinance remains the central issue at this COP, and perhaps the most complex. Several deeply interconnected discussions are underway:Article 9.1: Developing countries insist that public financing from developed nations is a binding obligation that cannot be replaced by private investment.Adaptation: A strong consensus is forming to triple the adaptation finance goal (to about USD 120 billion annually) while improving transparency and direct access to funds.The Baku–Belém Roadmap: This initiative seeks to scale up global climate finance to USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035 through a combination of public, multilateral, and private flows.Loss and Damage Facility: The fund is technically operational but not fully capitalized. New contributions from Spain and Germany are welcome — but insufficient to meet global needs.Tropical Forests Forever Facility: Brazil has proposed this as an “investment model” for tropical forest countries. Civil society has expressed serious concerns: the model depends heavily on volatile market investments and lacks safeguards to ensure the protection of local communities and ecosystem integrity. Adaptation progress, but under the shadow of chronic underfundingDiscussions on adaptation are unfolding on two parallel fronts:Indicators for the Global Goal on Adaptation. Ten years after the Paris Agreement, there is still no consensus on how to track adaptation progress. A working group narrowed approximately 9,000 proposed indicators down to about 100, but technical and political challenges persist. Some African and Arab countries have asked to postpone final adoption until they have the financial resources and capacity to implement them. A prevailing sentiment is: "no indicators without funding" — adopting metrics without support would repeat past mistakes.Adaptation finance. Although adaptation financing is not formally included within the Global Goal on Adaptation, the two issues are inseparable. Without adequate financial support, indicators alone will be ineffective. Following the agreement on a new climate finance goal at COP29, the current debate focuses on aligning that goal with adaptation needs — especially through technology transfer, capacity building, and direct-access funding channels. Substantial gaps remain, and negotiations continue to hinge on how to categorize financial flows (private vs. public, domestic vs. international).

Read more

Protecting the Environment Through Collaboration: A Community Science Experience

When environmental damage occurs, the first warning often comes from the people or communities directly affected. Residents living near a river are usually the first to notice waste being dumped or fish dying when the water is polluted. Similarly, who live near an open pit mine are the who see when illness becomes more common or when water begins to run scarce.One powerful way to turn lived experience into scientific evidence is through community science. This approach allows people to share, validate, and integrate local knowledge into scientific research and efforts to defend their territories.At AIDA, we believe in the power of science to advance environmental justice. That’s why we generate and apply scientific knowledge in the legal cases we support. Recently, we had the opportunity to take part in a community science initiative that helped us reflect on—and learn from—the value of this collaborative methodology and the shared knowledge it produces. Local Knowledge: A Powerful Response to Environmental Degradation In April 2024, at the request of the Poqomam Maya community of Santa Cruz Chinautla—a village near Guatemala’s capital—AIDA senior scientist Javier Oviedo and attorney Bryslie Cifuentes carried out a field visit to gather information and assess the solid waste pollution that has affected the community for years.One of their main objectives was to identify illegal dump sites on the banks of the Chinautla River. The disposal of waste and debris in this area has contaminated both the soil and waters of this tributary of the Motagua River, the longest river in Guatemala.While preparing for the trip, Javier realized the team would face several challenges. The time available would not be enough to collect all the necessary data, and the team’s limited familiarity with the area could make locating the dumpsites difficult and potentially unsafe.Then Javier had an idea: to involve members of the community in supporting the team with this task.His plan made perfect sense—after all, who better to locate the illegal dumpsites than the people who know the territory best? Beyond that, by witnessing the impacts of pollution firsthand, community members could also appreciate the importance of documenting these issues.I spoke with Javier about how this idea came about, and he shared the following: Beyond seeking support from community members, this approach was rooted in a recognition of the irreplaceable value of their knowledge as residents of their territory. How the Work Was Carried Out Javier’s idea was that, with the help of an accessible and easy-to-use mobile app, community members could send information about illegal landfills directly to the AIDA Science team, who would then validate and analyze the data.To make this possible, the team designed a form specifying the data they needed to collect: the location of the landfill, its dimensions, the type of waste identified, associated social issues, and other relevant details.In Chinautla, two community residents, along with authorities from the Poqomam Maya village, visited several landfills they had previously identified with Javier and Bryslie. During these visits, Javier showed them how to use the app and fill out the form. Later, one of the residents continued the process independently.Thanks to this collaborative effort, data was collected on 10 of the most critical illegal dumpsites. While this does not capture all of them—unfortunately, many more exist—this sample allowed the team to estimate the extent of waste and debris pollution in the community and to illustrate how poor management has exacerbated the problem.The information gathered was crucial in highlighting the severity of the pollution, demonstrating the continued use of illegal dumping, and exposing the municipal authorities’ failure to meet their legal obligations regarding waste management.This evidence formed the basis for the lawsuit the community filed against the municipality of Chinautla in October 2024, citing the lack of measures to address river and soil contamination caused by inadequate waste management and illegal landfills. In June 2025, an appeals court ordered the municipality to take action to address the serious environmental crisis affecting the community. Lessons Learned from the Experience According to Javier, involving the people of Chinautla in a knowledge-building process led to mutual learning.For community members, it meant acquiring new technological skills. For the AIDA team, it prompted new questions about how to move knowledge-sharing with a community beyond simple collaboration.Javier summarized his learnings in three points: At AIDA, science is a core part of our work and a key element of the strategic litigation we pursue to protect and defend a healthy environment across Latin America. Involving the communities we support in this process broadens our perspective, allowing us to integrate their knowledge and experiences into the science we seek to build.

Read more

Science in the Service of Environmental Justice

By David Cañas and Mayela Sánchez* Science—or rather, the sciences—are the systems of knowledge that different social groups have developed over time to describe the phenomena of nature and society. Thanks to these knowledge systems, humanity has been able to find solutions to countless challenges, and today, more than ever, they must respond to global crises such as climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss.Understanding ecosystem processes is essential for protecting the environment and providing verifiable, replicable evidence of natural phenomena and the impacts of human activities. It also enables the development of innovative solutions to protect and restore the environment.For science to contribute meaningfully to environmental justice—a concept centered on ensuring that all people enjoy a healthy environment—scientific work must be grounded in the realities of the people and communities affected by environmental degradation, who live in or rely on ecosystems vulnerable to harm. It must also be built on empathy and respect for other forms of knowledge, while seeking to reduce social inequalities.At AIDA, science is a central part of our work, supporting and complementing the strategic litigation we pursue to protect a healthy environment in Latin America. Through science, we can demonstrate the environmental impacts caused by human activities and hold those responsible accountable. How Do We Do Science at AIDA? The AIDA scientific team is a multidisciplinary group of professionals specializing in diverse fields, including geography, geology, biology, marine biology, oceanography, anthropology, and economics.Among other tasks, they collect and develop scientific evidence to strengthen the legal arguments in the cases we support across our various lines of work—from protecting the ocean and other critical ecosystems to defending human rights, such as the right to health and access to safe drinking water.The strategic use of science has been central to AIDA’s work since the organization was founded more than 25 years ago. One early example is the case of La Oroya in Peru, where a group of residents sued the government for failing to protect them from decades of heavy metal pollution caused by a metallurgical complex.Then we did something that had not been done before: we connected existing studies with the lived reality of La Oroya. This approach allowed us to demonstrate the relevance of the case and establish a clear link between pollution and its impact on the health of the city’s residents. Our analysis, compiled in the report La Oroya Cannot Wait, served to build the legal case and formulate proposals to the Peruvian government for corrective and preventive measures to address the problem. In 2024, in a decision that set a historic precedent for state oversight of industrial pollution, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights held the Peruvian state responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparations measures. Among the scientific team’s more recent contributions is a geospatial analysis of the Salar del Hombre Muerto in the Argentine provinces of Catamarca and Salta. Using maps and satellite imagery, the team documented water loss in this ecosystem caused by lithium mining.Another example is the expert report on solid waste pollution in the tributaries of the Motagua River in Guatemala, in which we recorded and characterized illegal dumps along the banks of the Chinautla River. This work enabled the affected communities to gather the evidence needed for the lawsuit they filed against the municipality of Chinautla for failing to address the contamination of rivers and soil caused by inadequate solid waste management. The Right to Science When science serves social and environmental justice, its benefits extend to everyone. This purpose was recently upheld by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in its Advisory Opinion 32, which recognizes the “right to science” as the right of all people to enjoy the benefits of scientific and technological progress, as well as to have opportunities to contribute to scientific activity without discrimination.The Court also recognized indigenous, traditional, and local knowledge as equally valid forms of knowledge. This acknowledges how the deep understanding that indigenous peoples and local communities have of their environment—their worldview based on respect and interdependence, and their spiritual connection to nature—has been fundamental to ecosystem conservation.As an organization that uses science as a tool for environmental protection, we believe in a science that embodies these principles: one built on dialogue between different forms of knowledge, whose benefits reach all people, and which contributes to the socio-ecological transformation the planet urgently needs. *David Cañas is AIDA's Interim Director of Science; Mayela Sánchez is our digital community specialist.

Read more

A Practical Toolkit for Using Advisory Opinion 32/25 in Climate Justice Work

READ AND DOWNLOAD THE TOOLKIT The climate crisis is already affecting people and communities across Latin America and the Caribbean—damaging homes, livelihoods, ecosystems, and the fundamental right to a healthy environment.Advisory Opinion 32/25 of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights is the first of its kind to establish that both States and non-State actors—including companies—have clear and binding legal obligations to confront the causes and consequences of the climate emergency as a human rights issue.The historic interpretation, made public on July 3, 2025, gives human rights and environmental defenders a powerful new tool to demand action and justice.But how can this decision be used in real cases, campaigns, and policies today? A Legal Toolkit for Climate JusticeTo help answer that question, more than 20 experts and organizations—including AIDA—created a new publication analyzing the Court's decision with an emphasis on its practical applications.Climate Justice and Human Rights: Legal Standards and Tools from the Inter-American Court’s Advisory Opinion 32/25 contains 14 briefs, organized into four key areas:Foundational Rights and Knowledge;State and Corporate Obligations;Rights of Affected Peoples and Groups;Environmental Democracy and Remedies. Each brief contains:Context and background to situate the issue.A clear legal analysis of the Court’s key contributions.A critical look at how these standards can be applied in practice.Identification of opportunities to advance advocacy and litigation, as well as the gaps that remain. All content was rigorously peer-reviewed to ensure clarity and accuracy. Why Does This Matter Now?With OC-32/25, advocates and local communities across the region now have:Stronger grounds for litigation—incorporating human rights standards into climate-related cases.Legal leverage for corporate accountability—clarifying businesses’ duties to prevent and remedy harm.Arguments to expand protections for those most affected: children, women, Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendant communities, and environmental defenders.Policy tools to demand national climate actions aligned with human rights. In a region facing disproportionate climate risks, this decision shifts power toward communities and movements seeking justice.What You Can Do With This ToolkitThis publication is a tool to facilitate understanding of the Court's decision and promote concrete legal and political actions to protect communities and ecosystems from the climate emergency.It is addressed to individuals, communities, organizations, and networks working on the climate crisis and human rights issues, providing them with standards and practical recommendations to strengthen their litigation and advocacy strategies and efforts.In short, it's designed to help you incorporate strong legal arguments your work, including:Shaping urgent protection actions for frontline communities.Strengthening advocacy campaigns with legal backing.Informing climate legislation and public policy debates.Supporting community-led demands for adaptation and resilience.Integrating human rights standards into strategic litigation. Whether you are a lawyer, organizer, community leader, or policymaker—this toolkit can help you to turn legal standards into real protection and accountability. A Call to ActionLatin America has contributed least to global emissions but is among the most impacted by climate harms. OC-32/25 opens a new chapter: one where the defense of human rights is also the defense of our climate.Now is the time to use this decision to advance justice across the region.Together, we can transform this legal milestone into tangible protections for the people and places who need them most. READ AND DOWNLOAD THE TOOLKIT

Read more