Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

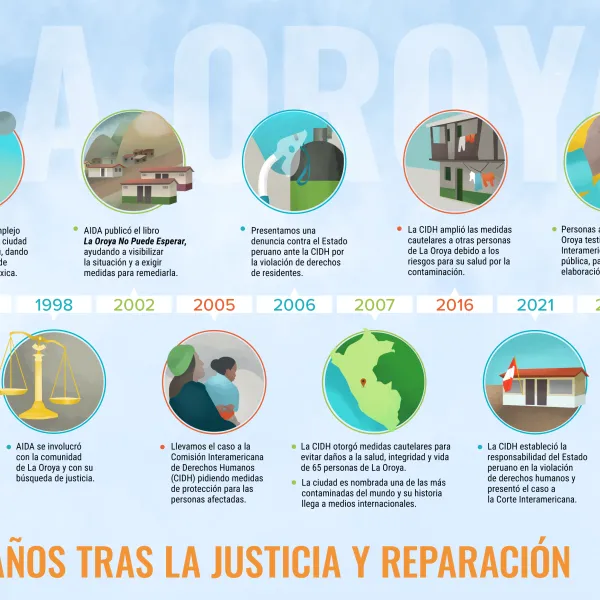

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Peru must find a comprehensive and sustainable solution for La Oroya

We call on the President-elect of Peru to take into account, in any assessment of or decision about La Oroya, the rights of the population affected by the city’s severe pollution. La Oroya, Peru. On July 6, the President-elect of Peru, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, visited the Metallurgical Complex of La Oroya (CMLO) and announced to its workers that it was necessary for the next Congress to approve a law to extend the deadline for liquidation of the Complex. This, he said, would give the company time to secure investors and finish the copper circuit. He also asked the workers and people of La Oroya to march on Congress to support his proposal. Reflecting on these public statements, the Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos (APRODEH) and the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense would like to express the following: The city of La Oroya deserves the full attention of all levels and sectors of government to resolve in a comprehensive, specialized and sustainable way the demands of the population that, at various times in its history, has suffered, and continues to suffer, violations of their basic human rights, including the right to life, health, integrity, work and a healthy environment. Regarding the right to work, La Oroya requires a deep assessment that permits the State to propose and implement not only remedial actions, but also actions that will guarantee decent and lasting work that will sustain adequate living conditions for the entire population. No action can resolve the underlying problem in La Oroya if it does not provide a guarantee of public health for residents. In that regard, we would like to remind the President-elect that since 2007 a group of residents from La Oroya have been the beneficiaries of precautionary measures granted by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights that safeguard their life and personal integrity before the impacts of highly polluted air, soil and water. In May 2016, the Commission extended those precautionary measures to include new beneficiaries. In the corresponding resolution, the Commission stressed that harm to the health of the beneficiaries is exacerbated due to the lack of comprehensive medical care offered by the State. Its also worth noting that a case is pending before the Commission which seeks to hold the Peruvian government responsible for the violations to the population’s basic rights to life, health, and integrity—as well as to the rights of children—due to the lack of control of pollution in La Oroya and the lack of effective medical care for those affected by it. We call on the President-elect to take into account, in any evaluation or decision on La Oroya, the rights of the population affected by the pollution. This should be done responsibly and with a comprehensive vision that guarantees the rights to life, health, work, and a healthy environment. It is inconceivable to favor the development of any economic activity over the health of the people. The incoming government faces the challenge of finding a comprehensive and sustainable solution for La Oroya, one that fully respects Peru’s national and international obligations to human rights and the environment.

Read more

Statement on the murders of environmental defenders in Honduras and Brazil

Threats to, as well as the intimidation, harassment and murder of environmental defenders must stop now! Yesterday we learned of the senseless murder of Lesbia Yaneth Urquía Urquía, a defender of the environment and indigenous rights who fought against the construction of the Aurora I dam in La Paz, Honduras. In a similar tragedy in Brazil, last month authorities found the lifeless body of Nilce de Souza Magalhães, a recognized leader of the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB), who worked for the rights of Amazon communities affected by large dams, predatory fishing practices and other threats. Both instances reinforce a tragic trend in Latin America, a region home to seven of the ten most dangerous countries in the world for environmental defenders. According to Global Witness, 185 environmental activists were assassinated worldwide in 2015; two thirds of them were from Latin America. Now, more than ever, it’s time to call for accountability. Lesbia Yaneth worked in alliance with the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), and her death comes just four months and four days after the assassination of the Council’s leader, Berta Cáceres. Nilce disappeared in January, her body finally discovered on June 21 in the lake formed by the Jirau dam, against which she had fought in defense of the rights of her community. Regarding these unfortunate deaths, María José Veramendi Villa, senior attorney of AIDA’s Human Rights and Environment Program, said: “The increasing rate of murder of environmental defenders in Latin America is alarming. States must guarantee a favorable environment in which people can safely perform their work to protect the natural world. States must also investigate and appropriately punish those responsible for these violent acts. The murders of those who bravely defend the environment must not go unpunished. Threats to, as well as the intimidation, harassment and murder of environmental defenders must stop now!”

Read more

Activist Deaths Demand Accountability

Last year 185 environmental activists were murdered world-wide, two-thirds from Latin America, according to Global Witness. Of the ten most dangerous countries in the world for environmental defenders, seven are in Latin America. The brave activists we lost were killed for resisting mines, dams, and other destructive industrial projects. Now, more than ever, we must demand accountability. For the loss to the environment, the loss of indigenous cultures, the loss of human rights. That just got harder. On May 23 the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights announced a severe financial crisis leading to “suspension of [scheduled] hearings and imminent layoff of nearly half of its staff.” While the Commission has long been short on funds, this is the worst financial crisis it has ever seen. The Commission depends on funding from the Organization of American States (OAS), governments in the Americas and Europe, organizations, and foundations. Nearly all governments have decreased or failed to honor their financial commitments. The financial crisis demonstrates that our work, and the work of colleagues, communities, and movements, is having an impact. The Commission has produced important decisions in cases involving indigenous and community rights, land and environmental protection, and destructive development projects. For a few years countries have complained that the Commission is going beyond its mandate in cases involving development projects. But of course, when development projects violate human rights, they clearly fall within the purview of the Inter-American Human Rights System. The Belo Monte Dam case provides clear evidence that this manufactured crisis is a result of our effectiveness. In 2011 the Commission granted the precautionary measures our colleagues and we requested on behalf of affected indigenous communities. Brazil reacted by immediately withdrawing its ambassador to the OAS and by withholding funding for the rest of the year. A new ambassador did not return until 2015 and Brazil’s payments haven’t normalized since. In addition, after the precautionary measures were issued Brazil started an aggressive process to “reform” the Commission that ended by weakening its power. At AIDA we have analyzed how the crisis affects our cases before the Commission; how it affects future cases that need international attention; and how it affects human rights protection in the Americas. Current cases will likely be delayed. Our case on toxic poisoning in La Oroya, Peru is already seriously delayed. The Commission has promised to release a report on the merits so the case can be taken to the next level, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. We have been told the Commission will approve the report, which has been completed, this year—despite losing 40% of its staff. This remains to be seen. Of course, we have contacted the Commission and stressed the importance of advancing the case. Informally, some judges from the Inter-American Court have indicated their eagerness to receive the case. Processing the Belo Monte case has only just started, after pending four years at the Commission. Strong political pressure from Brazil will likely delay it further. But political pressure on Brazil and the Commission can help the case move faster. As Belo Monte is linked to the biggest corruption scandal in Brazil, maybe the Commission will understand how relevant it is to advance the case. We will continue advocating for priority processing. New cases require further evaluation. We plan to bring at least one new case to the Commission soon, because unless we meet a deadline in a few weeks, the statute of limitations will prevent its consideration. All domestic remedies have been pursued; the Commission represents the last chance for justice. Despite the uncertainties of the current situation, it is important to preserve our clients’ rights in case the Commission’s funding is brought back to an adequate level. In other cases, we are looking for different ways to achieve justice. For example, we are exploring more than ever the use of national courts and national authorities. In addition, we are looking for new ways to engage financial institutions to prevent funding of projects that harm the environment and human rights. We are working with other organizations to develop response strategies. One of our attorneys, Rodrigo Sales, a Brazilian lawyer, recently represented AIDA at the General Assembly of the OAS. He advocated for human rights solutions in the region, among other issues. We consider collaboration and cooperation among the human rights and environmental communities to be essential. We need to stand together, showing governments and the public that human rights and the Commission are of vital importance. The financial crisis of the Commission—an international entity for hearing and resolving hemispheric human rights concerns—is an urgent issue that requires common understanding, thinking, strategizing, and acting. AIDA is working to make this happen.

Read more