Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

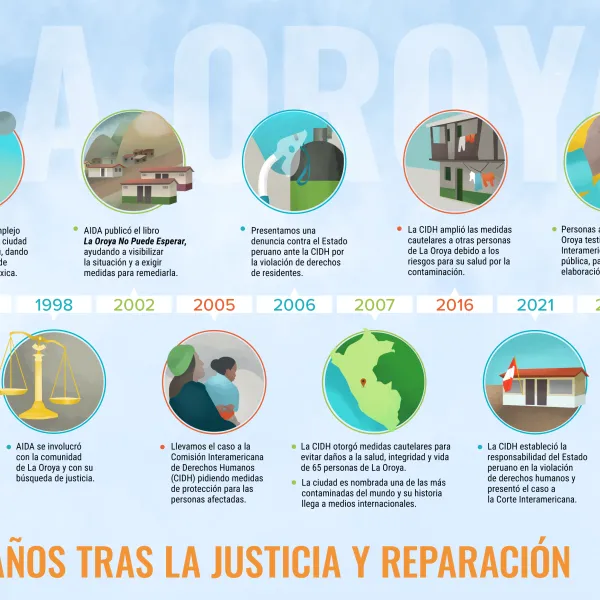

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Indigenous People of the Americas Have New Hope for Justice

By Astrid Puentes Riaño (text originally published in Animal Político) June 15 was a historic day. After 17 years of negotiations, the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was approved. That’s cause for celebration. The Declaration brings advances on many fronts. It means States must commit to respecting the rights of indigenous peoples, including their rights to land, territory, and a healthy environment. It means respecting sustainable development. It recognizes that violence against indigenous women “prevents and nullifies the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms.” And it reinforces the rights of indigenous peoples to participation; to prior consultation; and to free, prior, and informed consent – particularly when they’re faced with harm to their territories. The need for effective justice As the Organization of American States was approving the Declaration, activists held a Global Day of Action to call for justice for Berta Cáceres, the Honduran indigenous rights defender assassinated on March 3. These simultaneous events demonstrate the lack of effective justice in the region. Latin America yearns for justice, particularly with regard to human rights violations caused by extractive, energy, tourism, and infrastructure projects. The events also highlight the urgent need to put declarations and international obligations into practice. Berta’s death was foreshadowed. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights asked the Honduran government to take precautionary measures to protect her life, which the government did not do. Two days after her death, the Commission also requested protective measures for the organization she led, the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH). Just days later, however, Nelson García, another of the organization’s members, was assassinated. The primary demand on the Global Day of Action was to create a commission of independent experts to investigate the murders and to help uncover the truth. The assassinations of Berta and Nelson are not exceptions. More than 100 people dedicated to protecting their lands, forests, and rivers have been murdered in Honduras since 2010. And it’s not only there. Brazil, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Peru are four of the five most violent countries in the world for environmental defenders (alongside the Philippines). 2015 has been widely recognized as “the worst year on record” for those who defend the Earth. Towards real development Berta dedicated her life to defending rivers. At the time of her death, she was working to save her people’s territory from being flooded by the Agua Zarca Dam on the Gualquarque River. Indigenous communities there have taken stands against more than 50 extractive and energy projects affecting their land, the majority of which violate national and international law. Her case has thrust into the spotlight the realities of development in Latin America. Although governments—with the help of international financial institutions, national banks, and foreign investors—promote extractive, energy, tourism, and infrastructure projects as essential to development and poverty alleviation, the reality is quite different. Systematically, these projects are built in violation of laws and without adequate planning or evaluation of impacts on the environment and human rights. Sustainable alternatives are rarely evaluated at all. In fact, many of the projects pushed through in Latin America would not be viable in developed countries, where better technologies and safeguards are the norm. Special Rapporteurs to the United Nations have been calling attention to this issue for years. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights also recognized it in a recent report on extractive industries and their impacts on tribal and indigenous peoples. Unfortunately, the Commission is undergoing an unprecedented financial crisis because States aren’t making sufficient contributions. Some have delayed or withdrawn funding because of conflicts over the Commission’s rulings on extractive and energy projects in their territories. The clearest example can be found in Brazil, which reacted to the Commission’s call to suspend Belo Monte Dam construction by withdrawing its ambassador, initiating a thorough review of the Commission, and freezing financial contributions. Brazil has yet to re-establish a regular contribution to the body. Hope and opportunity For all these reasons, approval of the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is encouraging news. It’s essential that the rights and obligations it contains be upheld immediately. Starting with Berta’s case, States must demonstrate their seriousness. They must show, through action, that they recognize the problems facing the region; that they’re reaching for truth and justice; and that they favor real development to uplift their people. Latin America has a historic opportunity. Governments can finally join the 21st Century by respecting the rule of law, practicing what they preach, and promoting development that cares for our natural resources and those who most intimately depend on them.

Read more

NGOs call on Mexico to protect Mayan beekeeping communities affected by cultivation of genetically modified soy

The lives, health, and integrity of indigenous people are threatened by deforestation and contamination of their land caused by the cultivation of genetically modified soy. The situation is worsening because the Mexican government has not adopted effective measures to safeguard the rights of the communities. Washington D.C., United States. Traditional Mayan beekeeping communities, alongside a coalition of national and international organizations, have denounced the cultivation of genetically modified soy in the Mexican states of Campeche and Yucatan as damaging to the lives, health, and integrity of Mayan people, and to the health of the environment on which they depend. On July 25, a coalition of organizations filed a complaint on behalf of Mayan communities with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). The organizations are the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA); Centro Mexicano de Derecho Ambiental (CEMDA); Greenpeace Mexico; Indignación, Promoción y Defensa de los Derechos Humanos, A.C. (Indignación); and Litiga, Organización de Litigio Estratégico de Derechos Humanos A.C. (Litiga OLE). The health and way of life of affected people—especially children, pregnant women, and the elderly—are at increasing risk from deforestation and the use, during planting, of the toxic herbicide glyphosate, which has been proved to contaminate soil and water sources. The crops have been genetically modified to resist the herbicide, which leads growers to apply it in ever greater concentrations. The organizations asked the Commission to grant precautionary measures, an action that would urge the Mexican government to implement actions that protect the rights of communities and effectively halt the cultivation of genetically modified soy in Campeche and Yucatan. Leydy Pech, representative of the Mayan communities, said, “planting genetically modified soy in Mayan territory violates our rights and our culture, which has been passed down to us from our ancestors. Because of the cultivation of soy on our lands, we have lost medicinal plants, vital trees for local bee populations, and animals, and have even seen some of our archeological sites destroyed. This harms our Mayan identity and denies us the possibility of passing that knowledge on to our children; traditional knowledge that allows us to preserve the forest and generate wellbeing for our communities.” AIDA attorney María José Veramendi added, “the Mexican government has an obligation to apply the precautionary principle and take into account the health risks that come with glyphosate and the cultivation of genetically modified soy. By not doing so, the State is failing to comply with its duty to prevent violations of the rights of Mayan communities, who are exposed to the herbicide as it drifts on wind and contaminates water sources.” The affected Mayan communities live in the municipalities of Hopelchén, in the state of Campeche, and Mérida, Tekax and Teabo, in the state of Yucatan. Permits to cultivate genetically modified soy also affect other communities in the seven states of the Mexican Republic. The communities were not consulted, nor did they give their free, prior, and informed consent, before Mexico granted the permits necessary for the cultivation of genetically modified soy in their territory. Under international law, indigenous communities must be guaranteed the right to prior consultation and informed consent. What’s more, the planting has seriously affected traditional beekeeping practices, part of Mayan culture and one of the main sources of livelihood for the communities. In addition to requesting precautionary measures, the organizations filed a petition with the IACHR denouncing violations of the rights to land and communal property, to life and personal integrity, to a healthy environment, to work, and to judicial protection and access to justice. According to the organizations, the State has not taken effective measures to safeguard the rights of affected populations despite their efforts to seek justice in domestic courts. “Although the Mayan communities obtained a favorable ruling from the Second Chamber of the Supreme Court last November, the judgment did not resolve all the human rights violations,” explained Francisco Xavier Martínez Esponda, legal representative of CEMDA. “During the consultation process, authorities neither respect traditional manners of decision-making nor meet Inter-American standards for upholding this fundamental right. Since the Mexican State could not rule on all instances of rights violations or order their rectification, we have now brought the case before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.”

Read more

Six Colombian Wetlands of Global Importance

Colombia is blessed with sweeping mountaintops, rich jungles, and rivers that curve through the heart of it all. The country has three mountain chains, fertile volcanic soils, half of the world’s páramos (high-altitude wetlands), an equatorial climate with constant high temperatures, the Amazon forest, and the waters of the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean. Colombia is first in the world in diversity of birds and orchids, second in plants and amphibians, third in reptiles and palms, and fourth in mammals. To this I would add a long and diverse et cetera. Colombia’s environmental heritage includes six Wetlands of International Importance listed under the Ramsar Convention, a treaty that protects these environments. Their listing indicates their value not only for Colombia, but also for humanity. Where are they? Why are they important? What dangers do they face? 1. Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, Magdalena River Delta Estuary System. In the department of Magdalena, the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta is Colombia’s largest wetland lagoon. Here the fresh water of the Magdalena River mixes with the salty waters of the Caribbean Sea. It’s a refuge for both migratory and endemic birds. It’s in danger due to infrastructure projects including 27 kilometers of dikes, the burning and clearing of plant life, and drought. AIDA has worked with two Colombia universities to advocate for the protection of the Ciénaga before the Ramsar Secretriat. 2. Chingaza Wetlands System. The Chingaza system of lagoons and páramos hosts many species of endangered plants and animals, such as the spectacled bear and the frailejón, a succulent shrub in the sunflower family. It also serves as a refuge for migratory birds. According to the Humboldt Institute, the Chingaza páramo provides 80 percent of Bogotá’s drinking water. At AIDA, we advocate for the protection of the páramos, unique ecosystems that cover just 1.7 percent of Colombia’s continental territory but provide more than 70 percent of the nation’s drinking water. 3. Otún Lagoon Wetlands Complex. The Otún Lagoon Complex in Los Nevados National Park, in the Central Cordillera of the Colombian Andes, includes interconnected lakes, bogs, marshes, glaciers, and páramos. The area supports 52 species of birds, many of them endangered. The livestock industry, litter, forest fires, invasive species, and illegal tourism activities all threaten the area. 4. Baudó River Delta. Originating in the Serranía del Baudó, the Baudó River runs 180 kilometers through the department of Chocó and empties into the Pacific Ocean. A relatively short river, the Baudó swells from the region’s abundant rains and flows powerfully into the Pacific. The river delta’s main threats include indiscriminate mangrove removal and overfishing. 5. Estrella Fluvial del Inírida Wetlands Complex. This complex of wetlands occupies a transition zone between the Orinoco and Amazon regions, close to the sacred indigenous site of Cerro de Mavicure. According to the Ministry of Environment, the area is home to 903 species of plants, 200 species of mammals, and 40 species of amphibians. Critically endangered species, including otters, jaguars, and pink dolphins, struggle to survive there. These wetlands face threats from the illegal mining of coltan and gold, and the accompanying mercury discharge. The buffer zone also suffers from cultivation of drug crops, the livestock industry, and deforestation. 6. La Cocha Lagoon. In the indigenous language of Quechua, cocha means lagoon. In the Department of Nariño, 2,800 meters above sea level, sits Colombia’s second-largest lagoon. On its banks live fishermen, farmers, and descendants of the indigenous Quillacinga people. Tourists come to spot unique plant and animal species on the small island of La Corota. The livestock industry, intensive agriculture, deforestation, and erosion threaten the lagoon. Valuable Characteristics The Ramsar Convention protects these sites because of their fundamental role in both regulating water cycles and providing habitat for unique plants and animals, particularly aquatic birds. Ramsar also recognizes the wetlands as important sources of fresh water, which recharge aquifers. They even mitigate climate change. The Convention calls worldwide attention to these wetlands, which have “great economic, cultural, scientific and recreational value, whose loss would be irreparable.” Despite their tremendous value, Colombia’s wetlands face a growing number of threats: overexploitation, water loss, burning, deforestation, toxic contamination, large-scale mining, large-scale agriculture, roads that disrupt the natural water cycle, and climate change, among others. In recent years, they’ve been featured in some of Colombia’s most emblematic films, including El Abrazo de la Serpiente (Estrella Fluvial del Indira) and La Sirga (Cocha Lake). It is our moral and social duty—under international environmental law and the Ramsar Convention—to care for the delicate richness of the wetlands that we are so fortunate to have in our diverse little corner of South America.

Read more