Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

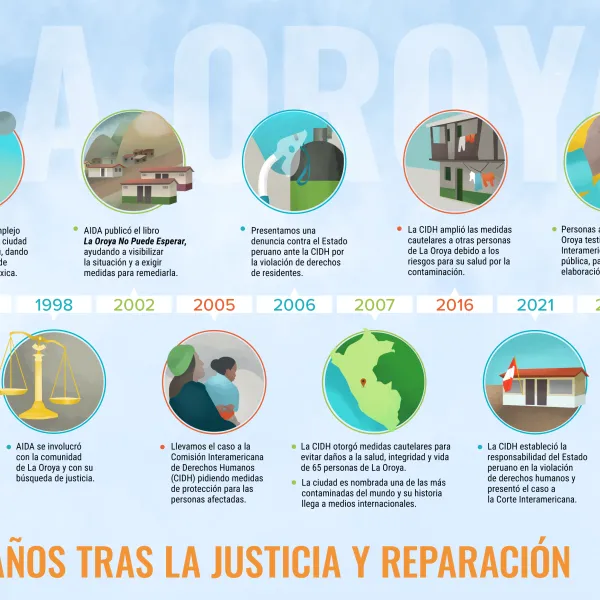

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

The bicycle: Can it be our principle mode of transport?

By Astrid Puentes Riaño, co-director, AIDA, @astridpuentes Have you ever thought that bicycles could be our main mode of transport, or is it already for you? I tell people that I cycle, and that I live in Mexico City! I love riding on two wheels for many reasons: it’s environmentally friendly, and it’s easy, fast, cheap and fun. Many times I’ve ridden past cars idling in traffic, leaving them behind as I arrive at my destination in less time than if I’d taken a car or bus. Although it seems incredible, I hardly ever take a car. This might seem crazy given that we are in the modern era and I live in Mexico City, but its doable. I use Ecobici, a public rental service for bicycles. It’s not perfect, but it works well enough. I’m not saying that bicycles should be the only option for everyone. It works for me because most of the destinations I ride to are within a reasonable distance. Of course, when I need to go somewhere with my two year old, I resort to other means of transport such as our family car. As we all know, the increasing use of bicycles and other zero-emission modes of transport help to combat climate change in our cities. Sustainable transport alone will not provide the panacea for solving global warming, but it does go a long way in reducing its impact. The case of The Netherlands Riding a bike, especially in Latin America, can sometimes be more of a challenge than an adventure. I found a BBC article that explains why some countries like The Netherlands use bicycles on a grand scale. The reasons why are surprisingly simple. The country has: Excellent bike path infrastructure, with enough space for everyone to cycle, including children. A bicycle-friendly culture: Motorists respect cyclists because in most cases they either know someone who is a cyclist or they cycle themselves. Strict traffic rules for everyone: Motorists and cyclists alike face hefty fines if they park poorly on the street, travel in the wrong direction or do not follow traffic light rules. Tolerant neighbors allow cyclists to park their bicycles outside their houses, which is clearly a safe place to leave them! How can this be achieved? An interesting aspect in the case of The Netherlands is that civil society pressure and the oil crisis were decisive factors that influenced a considerable change in the country’s transport system. Like most countries in the 1950s and 1960s, the number of road vehicles in The Netherlands grew significantly and, with it, a rise in traffic-related accidents. The number of people killed in 1971 as a result of traffic accidents was 3,000, 450 of whom were children, according to the BBC. The sharp increase in deaths prompted a social movement called “Stop the Child Murder,” which called on the government to improve road safety for cyclists. These incidents, together with the oil crisis of the 1970s, led to changes in government policy, the construction of new bike infrastructure, improved safety standards and, above all, the framework for The Netherlands to take a new bicycle route of its own. Helmet or no helmet… Curiously, it is not mandatory to wear a helmet when bicycling in The Netherlands, as is also the case in much of Europe. Wearing a helmet is not considered necessary given the very low number of accidents and the high level of road safety. The obligation to wear a helmet is seen by many as an attack on the culture that promotes bicycles as a mode of transport. In Spain, there have been protests against government efforts to impose rules enforcing helmet use. In contrast: Cyclists of all ages must wear helmets in Australia and Dubai. It is mandatory to wear a helmet in some Canadian provinces, not others. United States federal law does not require cyclists to wear helmets, but cities like Dallas require helmets for cyclists of all ages, while only those under the ages of 16 and 18 in California and Washington D.C., respectively, are required to do so. Certainly any government attempt to implement policies on helmet use in Latin American cities would be difficult. On the one hand, it is a very real danger to cycle on busy cities, especially if drivers are not accustomed to sharing the roads with cyclists. On the other hand, mandatory helmet requirements could act as a disincentive to people in choosing whether to take up riding bicycles. Something to consider is that helmets alone do not prevent all accidents. A great majority of accidents -- children falling off their bicycles or collisions on the congested streets of Bogota and in other Latin American cities -- can be avoided if appropriate security measures are put in place. I myself had an accident at the age of three when my uncle took me for a ride on his Super Monareta (a Colombian brand of bikes) near my grandmother’s house. My left foot got stuck in the spokes of the rear wheel, badly injuring my inner foot and resulting in the destruction of my best pair of shoes. Fortunately, I came away with only a scar. But it could have been much worse. Progress in Latin America It’s pretty much impossible to compare our countries with The Netherlands. But I think the progress made and lessons learned there hold the key to bicycle reform, and are well worth noting. The good news is that various Latin American capitals have taken action to encourage the use of bicycles. Bike paths are expanding: Bogota has 297 km, Santiago is planning to build an additional 400 km in the inner city, Mexico City reached 42 km in 2012 and Buenos Aires has about 90 km. In reality there is still a great deal to be done and, fortunately, citizens are becoming more involved in the issue, demanding better infrastructure, improved security and air quality to ride something that is more than just a child’s toy. Hopefully progress will continue and we’ll finally see positive changes toward the adoption of fun, environmentally friendly and cheap forms of transport like cycling. What do you think? Do you dare ride a bike?

Read more

"No thank you" says the Green Climate Fund Board to transparency and civil society input

By Andrea Rodríguez, legal advisor, AIDA,@arodriguezosuna Once again civil society organizations expressed disappointment at the lack of transparency and civil society engagement at the latest meeting of the board of the Green Climate Fund (GCF), an operating entity of the United Nations Convention Framework for Climate Change (UNFCCC). The 24-member board met June 25-28 in Songdo, South Korea to further advance a process of putting the GCF into operation. The GCF will operate as a mechanism for transferring funds from the developed to developing world in order to help developing countries finance adaptation and mitigation practices to combat climate change. Civil society organizations have been constantly asking the GCF board for better opportunities for civil society to effectively be involved in the GCF decision-making process. Organizations have sent letters to board members, advisors and the GCF Interim Secretariat. But these many attempts to draw attention and consideration to civil society’s concerns have come to no avail. The board has constantly closed the doors to civil society’s active and effective participation. At board meetings, civil society may only have two active observers in the meeting room: one representing the north and the other the south. The other accredited observers have to sit in an overflow room to watch the meeting. The two active observers may only engage in the meeting if invited by the co-chairs of the board. Only one intervention can be made per each agenda item of the meeting and for no more than three minutes each time. On the last day of the Songdo meeting, the co-chairs disallowed any interventions from civil society, claiming there was not enough time. Ironically, the most important decisions were made on the last day. Given these limitations imposed by the co-chairs, the two active observers in the meeting room approached several board members to share key points on different papers from the perspective of civil society. The co-chairs, however, penalized this action and forbade the active observers from talking to board members. Despite the frustration of the being undermined and excluded, civil society was hoping to win at least one battle at the meeting: getting the board to decide in favor of live webcasting. Live webcasting shows a commitment to accountability and transparency. It provides opportunities for people without the resources to travel to board meetings to get involved in the meeting while also limiting the CO2 emissions generated by each board meeting through a reduction in the number of international flights taken for attendance. Webcasting is widely used by climate-related funds and is even used by the UNFCCC, the international environmental treaty of which the GCF is part. In Songdo, the GCF board decided against live webcasting on the argument that it would be too expensive at US$20,000 to US$30,000 per meeting. The board’s reference prices, however, are far more than the market average of US$1200 per day. According to the Adaptation Fund (AF) Secretariat and its webcast provider, live-streaming of AF board meetings costs about $1,000-$1,250 per day of broadcast, depending on site specific issues. Instead of live webcasting, the GCF board agreed to make webcasts of the meeting accessible three weeks after the event upon registration. Civil society organizations believe that this three-week delay prohibits organizations from advocating on the issues related to the discussions and decisions at the meeting. The Green Climate Fund has decided to have a strategic focus on climate mitigation and adaptation and seek to maximize sustainable development. Nevertheless, it is difficult to understand how the fund would ever be able to maximize “sustainable development” if its decisions are not made with the support of effective stakeholder participation and engagement throughout the whole process.

Read more

There is a blot in the middle of the ocean…

By Florencia Ortúzar, legal advisor, AIDA The first time I heard about the mysterious “rubbish island” I was shocked. How could a huge floating mass as big as a country go unnoticed in the ocean without being on everyone’s lips? Incredibly, many people haven’t even heard of this Pacific Trash Vortex that grows larger every day, making it the world’s largest rubbish dump. A soup of what? The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, as it’s officially known, is one of the five floating rubbish dumps polluting our world’s oceans. It was the first to be discovered and is the biggest. It’s located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean between the U.S. states of Hawaii and California, about 1,000 kilometers off the coast of Hawaii. The size of the rubbish heap is difficult to determine. Estimates range from about 15,000 square kilometers (equivalent to the surface area of Antarctica or 8.1% of the Pacific Ocean) to 700,000 square kilometers (almost the surface area of Chile). Let me explain a little more about this sad and unusual phenomenon. The island of rubbish is not a solid island as such, nor a floating sheet of trash. Rather, it’s a soup of plastic particles floating in a gyre. Ocean currents collect thousands of tons of floating garbage and round them up in a giant vortex. The slowly rotating mass prevents the rubbish from dispersing. This soup has everything: abandoned fishing nets, plastic bottles, caps, toothbrushes, shoes and much more. But more than anything, the vortex consists of small particles of plastic created when the waves and sun break down larger pieces. This gigantic mass remains below the surface of the water in a column estimated to extend 30 meters deep. Paradoxically, despite its huge size, the rubbish dump is not easy to visualize as a whole and has not been captured in satellite images because of its location under the water. Worse, it is located in international waters, so no nation is responsible for the waste. After concerned scientists and environmentalists, the only people left to help clean up the mess are passengers on special cruise ships who visit the vortex to help remove some of the rubbish. In all, it’s a gigantic mess going unnoticed, growing slowly but surely in a no man’s land devoid of a god or the rule of law. A chance discovery In 1988, experts from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted the existence of the garbage patch in the North Pacific Ocean by analyzing local marine currents. But it wasn’t until a decade later when oceanographer Charles Moore officially discovered the trash heap, which was dubbed the "Eastern Garbage Patch." In July 1997, Captain Moore was sailing through the North Pacific Gyre when he came across miles and miles of synthetic pieces of debris, and an immense mass of floating garbage. It took the American one week to cross the accumulation of waste. In 1994, Moore established the foundation Algalita Marine Research to focus on the protection and regeneration of kelp forests and wetlands along the coast of California. But after his floating garbage island discovery, Moore dramatically changed the course of his foundation and dedicated it to raising awareness and promoting education about the garbage patch. (See Moore’s TED talk). Expeditions to the forgotten island Since its discovery, there have been various scientific expeditions to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and other floating garbage islands like it. Unfortunately, these trips have not managed to generate a significant amount of public awareness or impact outside environmental circles. Nobody seems to be willing to take responsibility or action. The most recent expedition in May was organized by the Society of French Explorers (in French) on a schooner called L’Elan, assisted by Captain Moore on board. The results of the mission have not yet been published. Hopefully now with the ability of social networks to disseminate information widely, the issue will generate more interest and make people aware of the huge amount of plastic we consume. What can we do? As mentioned above, the garbage island mainly consists of billions of plastic pieces too small to be seen. This makes it difficult for the debris to be removed from the ocean. You would have to put a very fine net across the surface of the water, which would disturb the ecosystem and essential marine fauna such as plankton, a key food source for ocean animals. What is more, accessing the polluted area would require a considerable amount of resources including manpower and expensive materials to undertake the difficult work out in the open seas. The task becomes even more unlikely where you consider that the garbage island is located in international waters where no country is sovereign (the tragedy of the commons). For now and until we come up with new technology that lets us travel back in time to prevent this disaster, the best and most sensible thing to do is to stop producing so much garbage, and especially to limit our consumption of disposable plastic. It is also important to help raise awareness of the problem so more people understand the effects of their consumerism, change their lifestyles and educate future generations who will be looking after the planet. The island of trash consists of materials that at one time helped revolutionize the world. Today we are surrounded by plastic: we eat and drink from it. We use it every day. It is present in nearly all of our activities. Plastic is almost a miracle product. Cheap, effective and virtually indestructible, it doesn’t break. It just disintegrates into smaller parts. The considerable durability of plastic means that almost all the plastic molecules ever created still remain somewhere on the planet. Now at least we have a better idea on where they end up: on rubbish island.

Read more