Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

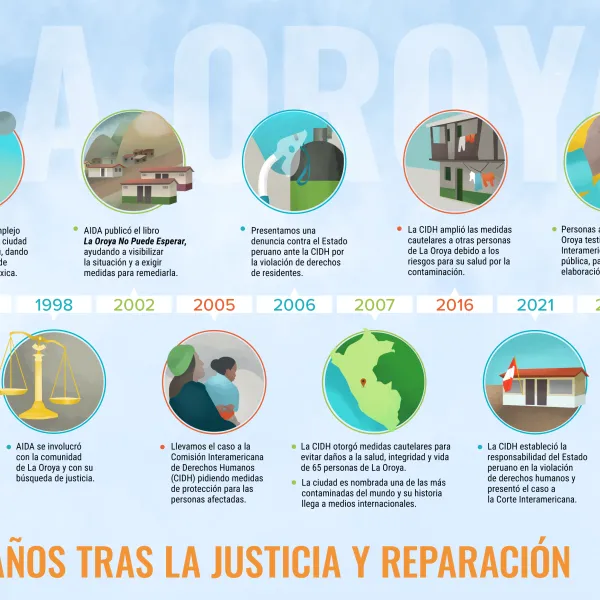

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Latest News

Report on the situation in La Oroya (Peru): When investor protection threatens human rights

The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) presented a balance of the controversial case of industrial pollution. Huancayo, Peru – The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) released a report on the situation in La Oroya, a city in the central Andean region of Peru that is at the center of a controversial case of industrial pollution caused by a poly-metallic smelter in operation since 1922. For decades, the people of La Oroya have been exposed to high levels of air pollution stemming from the complex’s emissions of toxic substances including lead, cadmium, arsenic and sulfur dioxide. In the middle of the 2000s La Oroya was identified as one of the 10 most polluted cities in the world. According to independent studies, 97% of children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years, and 98% of those between 7 and 12 years old still have high levels of lead in their blood. The percentage reaches 100% in La Oroya Antigua, the area closest to the smelter. The effects of lead poisoning are irreversible. Doe Run Peru, a subsidiary of the U.S.-based Doe Run Company, began operating the complex after its privatization in 1997. Both the company and the Peruvian State have failed to comply with their obligations to prevent environmental impact and respect the human rights of the population of La Oroya. In response, the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA) and other organizations requested the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in 2005 to issue precautionary measures for people whose health was at serious risk from the pollution in the city. On August 31, 2007 the IACHR ordered the State to adopt measures to protect the health, integrity and life of a group of residents of La Oroya. The precautionary measures require Peru to provide a specialized medical diagnostic to the beneficiaries plus specialized and adequate medical treatment to those who, based on the diagnosis, are in danger of irreparable damage to their physical integrity or lives. Also since 2007, a complaint against Peru has been pending before the IACHR for the violation of human rights due to the toxic emissions from the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex. AIDA, APRODEH, Earthjustice and the Center for Human Rights and Environment (CEDHA) are representing the victims and the beneficiaries of the precautionary measures in the case. “AIDA has been working and monitoring the situation in La Oroya for over a decade. Over this time we have seen the extent of the damage to victims’ health in La Oroya due to the pollution that they have been and continue to be exposed to. The State must assume its obligations and fully comply with the IACHR´s precautionary measures that are in effect”, said Maria Jose Veramendi, an AIDA legal advisor. Meanwhile, parents of children with high levels of lead in their blood have tried to obtain compensation for the damages through a collective action in the United States (Missouri), headquarters of the complex’s parent company The Renco Group. In late 2010, Renco initiated international arbitration alleging its rights as a foreign investor as guaranteed by the Free Trade Agreement between Peru and the United States were violated. Renco asked for compensation of $800 million. “The company not only denied the impacts on the citizens and tried to evade responsibility, but in the face of the protests it pursued a campaign of stigmatization and attacks against those who were trying to defend their rights”, said Souhayr Belhassen, president of the FIDH. This case illustrates the conflict between international human rights law and investor protection. It also exposes the legal strategy of the companies allegedly involved in human rights violations that seek to evade responsibility and deny victims their right to reparation. The FIDH report, entitled Metallurgical Complex of La Oroya: When investor protection threatens human rights, includes a series of recommendations directed at the Peruvian authorities and the company involved. AIDA and APRODEH, as organizations representing the victims of La Oroya before the Inter-American Human Rights System, thank the FIDH and believe that the report is an important contribution to visualize the increasingly serious human rights violations suffered by the residents of La Oroya, who still expect the State to recognize its responsibility and bring justice to their claims. At the same time, the Archdiocese of Huancayo, whose role in defending the right to a healthy environment in La Oroya has been crucial, says the report is a major contribution to its work. See de PDF version of the report.

Read morePeru’s efforts to require La Oroya clean up should not be chilled by investment arbitration

San Francisco, CA – The following is a statement from the international organizations Earthjustice, the Inter-American Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), the Peruvian Society for Environmental Law (SPDA), and Public Citizen: In 1997, Doe Run Peru (DRP), an American company, bought from the government of Peru a metallurgical complex located in La Oroya, Peru. As a condition of the purchase, DRP agreed to comply with a number of environmental requirements aimed at protecting the environment and health of the local population. For 15 years, Doe Run has failed to fulfill these commitments. Now, rather than live up to its responsibilities, DRP and its parent company, the Renco Group, are using questionable legal and political tactics to continue to avoid its commitments—most prominently through an international arbitration case against the State of Peru. In 2011, the Renco Group brought a claim in an international arbitration tribunal for US $800 million against the State of Peru, alleging Peru’s non-compliance with and failure to honor its legal obligations. However, Peru should not be deterred from its efforts to require the company to clean up La Oroya. Here are just a few of the reasons why: 1. Even if the Peruvian Congress were to grant DRP another PAMA extension, the liability claims in Renco’s arbitration case against Peru would remain because Doe Run’s case against Peru involves more than the PAMA extension contemplated in the proposed law. The Peruvian legislature is currently debating a bill to extend Doe Run’s environmental remediation obligations (known by its Spanish acronym, PAMA) for a third time. The legislature’s Energy and Mining Committee quickly approved the bill. However, policymakers should not presume that Doe Run will drop its arbitration case against Peru if the legislature grants the extension. Indeed, the company is likely to find it advantageous to keep the investment case going (or launch new ones) in order to pressure the government through the international arbitration proceedings. 2. The company is using the investment arbitration to insulate itself from penalties in a case in Missouri courts. In 2007, attorneys filed lawsuits in Missouri (where Doe Run is headquartered) on behalf of children in La Oroya alleged to have experienced serious health problems from exposure to toxic pollution from the smelter in Peru. In a similar case resolved last year regarding harms to 16 children from Missouri, the Missouri court awarded the children US $358 million. In the aforementioned 2007 case about La Oroya in Missouri, DRP has insisted that the Peruvian government—not the company—should be held liable for these tort claims (even though the children are only claiming damages that occurred after Doe Run purchased the smelter). Therefore, the company will likely attempt to keep its international investment arbitration case alive until the Missouri case is resolved, so the Renco Group can use the arbitration to force Peruvian taxpayers to pay any penalty awarded against DRP. 3. The Renco Group is using the arbitration case to move the Missouri case to federal court and evade liability. Doe Run has aggressively tried to derail the Missouri case by insisting that the La Oroyan children’s claims be heard in US federal courts, where it appears Doe Run believes it is more likely to win the case. Twice, the Missouri judge refused to allow the company to do so. After launching the international investment arbitration against Peru, however, Doe Run made a new argument, and convinced the judge to move the La Oroyan children’s case to US federal court, which has jurisdiction over treaty-related claims. The Renco Group has an incentive to keep the international arbitration pending against Peru—regardless of whether the Peruvian legislature extends the PAMA—in order to maintain its argument that the case belongs in federal court 4. Giving in to the threat of the international investment arbitration would set a bad precedent for Peru and the world. As explained above, DRP is using the investment arbitration to serve many different interests. In each case, the common factor is that the arbitration threatens to make Peru—and Peruvian citizens—responsible for the contamination in La Oroya and any resulting penalties. If Peru responds to this threat by giving DRP special treatment at the expense of the children of La Oroya, it will send a message to DRP and multinational companies around the world that such threats are effective. This will weaken Peru’s ability to protect its interests, including the environment and human rights, in the face of corporate misbehavior. 5. DRP is using false arguments to try to shift the blame to others. In addition to the arbitration claims, DRP has long argued that Activos Mineros—a state-owned firm—should complete its PAMA obligations to remediate soils around the complex. Now DRP is claiming unfair treatment because Activos Mineros has not yet been required to do so. This argument makes no sense. It is well known that cleaned soils will quickly become re-contaminated if nearby smelter pollution continues. In Missouri, the authorities calculated that soils near the Doe Run smelter would be re-contaminated only a few years after Doe Run had remediated them at a cost of millions of dollars. Doe Run is well aware of this, yet argues that Peruvian taxpayers should spend millions of dollars cleaning soils in La Oroya that would be re-contaminated in mere months if the smelter were to reopen without first installing all necessary pollution controls. This would be a waste of resources and would not solve La Oroya’s health problems. Activos Mineros should indeed remediate the soils. But it makes no sense to do so until either DRP completes installing the control technology it has promised yet failed to deliver for 15 years, or after a decision is made to permanently close. The government of Peru should take these facts into account and make sure that it does NOT allow Doe Run to pressure it into reopening the complex in La Oroya. The government of Peru needs to ensure it is considering and protecting not only the rights of the workers, the economy of the region, and the health and human rights of the citizens in La Oroya that would be harmed by reopening the complex, but also protecting the national economic interests. Reopening the complex without clarifying the responsibilities for third party claims from cases such as the case pending in Missouri, would be folly and pose a significant economic risk for the nation. This could even result in economic costs for the people of Peru that exceed the benefits obtained from operating the complex. If the Peruvian legislature believes that it can or should extend the PAMA, it should insist on at least three non-negotiable positions. First, that the Renco Group drop its international arbitration claim. Second, that Doe Run agree that it will assume any liability in Missouri related to contamination stemming from the smelter in La Oroya. Third, that DRP complete all of its environmental requirements—before starting any operation—so that Peru can begin its soil remediation efforts and protect the health and human rights of the children of La Oroya. Every day that the fate of the La Oroya metallurgical complex remains undecided without a final solution to the contamination, the citizens of La Oroya suffer grave health risks which in turn increase the harms for which both DRP and the government of Peru could be held liable.

Read more

La Oroya before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

In an effort to compel the Peruvian government to resolve the health crisis in La Oroya, AIDA appealed to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in 2005, requesting that the Commission take urgent precautionary measures (in Spanish) to safeguard human rights. Working together with Earthjustice, CEDHA, and our Peruvian colleagues, we brought this case on behalf of more than 60 adults and children who live in La Oroya and suffer from health problems believed to be caused by the smelter’s pollution. The following year, after the government failed to heed Peruvian court mandates to clean up La Oroya, we submitted a full petition to the IACHR, asking the Commission to thoroughly evaluate the human rights situation and obligate the State of Peru to prevent the Doe Run Peru smelter from further contaminating the city. The Commission responded favorably to our efforts. In 2007, the IACHR requested that the State of Peru take precautionary measures to prevent irreversible harm to the health, integrity, and lives of the people of La Oroya. Specifically, as a first step, the Commission requested that the Peruvian government diagnose and provide specialized medical treatment to the group of people we represent. When the government was slow to comply, the Commission met with the parties again in 2008 and 2009, and successfully motivated the state to implement the measures appropriately, a process currently in progress. In August 2009, the IACHR accepted AIDA’s petition to fully evaluate the case against Peru. It based its decision on the fact that the illnesses and deaths allegedly resulting from the severe pollution constitute potential violations of the human rights to life and integrity. It also found that the State of Peru likely violated the public’s right to information when it manipulated and failed to publish important human health information. Finally, the Commission concluded that the State of Peru unjustifiably delayed compliance with the 2006 decision of the Peruvian Constitutional Tribunal, and thus may be violating citizen’s rights of access to justice and to effective domestic remedies. Now, several years after the IACHR first ordered Peru to provide precautionary measures, it is clear that the state’s efforts have been woefully inadequate. The 65 residents represented by AIDA have received spotty medical attention that falls far short of the “specialized” care that was promised, and the government’s efforts have not reduced health risks in a meaningful way. In March 2010, AIDA and its partners returned for another public hearing at the IACHR, to present evidence that the Peruvian government’s actions fail to satisfy the terms of the 2007 recommendations. Backed by findings from independent experts, AIDA argued that the medical evaluations conducted by the government were never completed and that the city is still contaminated by heavy metal pollution that causes a range of debilitating conditions, especially among children. The State denied these claims, insisting that it has taken sufficient action and the case should be closed. While we wait for a final decision on the case, AIDA will continue to pressure the Peruvian Ministry of Health to comply with its obligations, and to encourage the IACHR to maintain a spotlight on the Peruvian State until the pollution in La Oroya no longer threatens people’s fundamental human rights. Positive changes resulting from this case will not only benefit those we represent, but all residents of La Oroya. A decision from the IACHR will also create a vital precedent that can be applied in other cases throughout the hemisphere. IACHR hearing - La Oroya Follow us on Twitter: @AIDAorg "Like" our page on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AIDAorg

Read more