Project

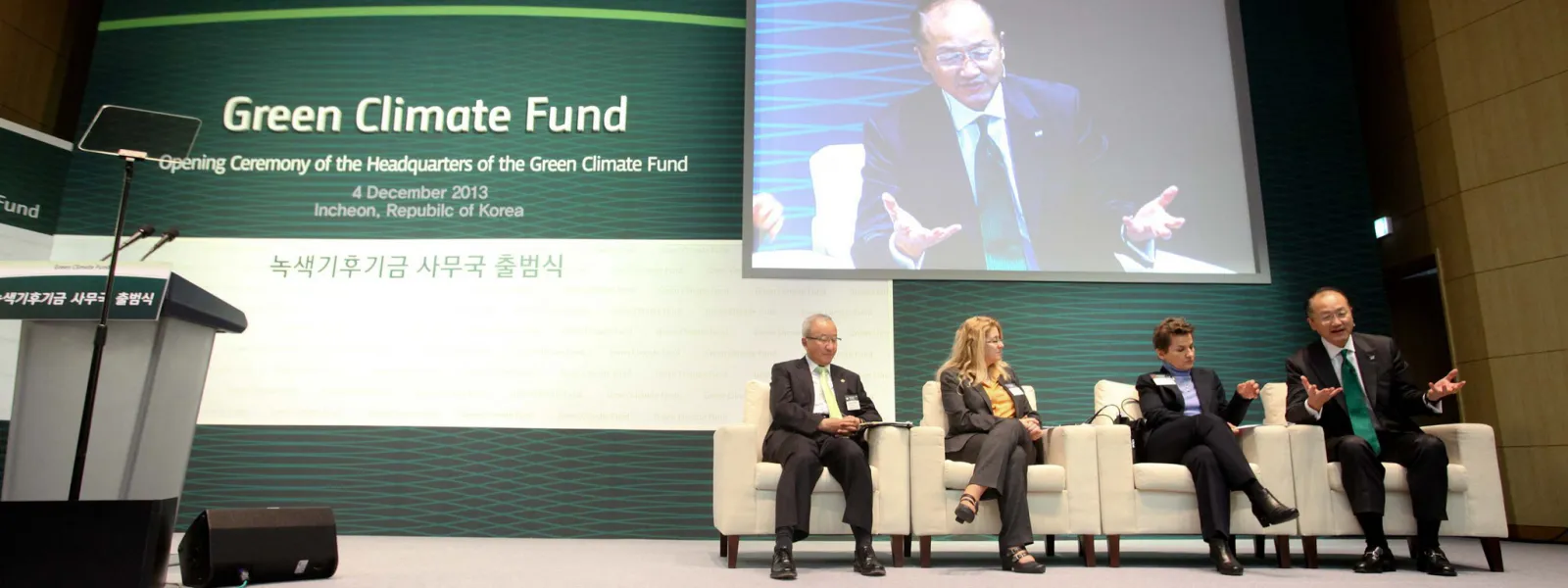

Photo: GCFAdvocating before the Green Climate Fund

The Green Climate Fund is the world's leading multilateral climate finance institution. As such, it has a key role in channelling economic resources from developed to developing nations for projects focused on mitigation and adaptation in the face of the climate crisis.

Created in 2010, within the framework of the United Nations, the fund supports a broad range of projects ranging from renewable energy and low-emissions transportation projects to the relocation of communities affected by rising seas and support to small farmers affected by drought. The assistance it provides is vital so that individuals and communities in Latin America, and other vulnerable regions, can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and address the increasingly devastating impacts of global warming.

Climate finance provided by the Green Climate Fund is critical to ensure the transformation of current economic and energy systems towards the resilient, low-emission systems that the planet urgently needs. To enable a just transition, it’s critical to follow-up on and monitor its operations, ensuring that the Fund effectively fulfills its role and benefits the people and communities most vulnerable to climate change.

Reports

Read our recent report "Leading participatory monitoring processes through a gender justice lens for Green Climate Fund financed projects" here.

Partners:

Related projects

Listening to indigenous peoples to save the planet

More than 400 indigenous groups live throughout Latin America, many at home in the region’s protected areas, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Their ancestral knowledge of and connection to the natural world has been recognized as a way to guarantee a healthy environment and cope with climate change. Yet society seldom listens to them to learn how to best protect our natural resources. Pu’amé is a Cora expression that means “you first.” It’s used to give way to someone, but also as an expression of respect when someone is talking; it’s a way of saying, “Continue, I’m listening.” Julián López, a Náyeri indigenous leader who speaks Cora, explains this to me in a meeting with members of rural communities in Nayarit, México. I’ve come to listen. During the meeting, pu’amé becomes a way of helping us pay attention and understand. To listen to representatives of indigenous communities is to confront a different worldview, particularly for those of us who exist in the urban, western world. While our way of life is focused on consumption and dependent on exploitation, indigenous communities see the Earth as a source of bounty that requires care and gratitude; it provides them with food and health. These conflicting visions have resulted in the incessant violation of indigenous rights, putting at risk not only their cultural integrity, but also their very lives. To achieve real dialogue with indigenous peoples, you must understand them, Julián tells me, while teaching me a few words in Cora. Opposing visions of development Representatives of rural Mexicanero and Cora communities from the upper and lower regions of the San Pedro Mezquital river basin have come to this meeting to discuss the Las Cruces hydroelectric project. Their concerns are many: if the dam, or any other sacred site, is constructed, what will be the fate of their children and their sacred sites? What will happen to the life of the river, the quality of the fish, and the natural balance? Odilión de Jesús López, also Náyeri, expresses his concern that authorities “don’t value that caring for nature is for the good of all.” He questions the pushback he has received for defending the river and his community’s sacred sites. “How do we use sacred sites? We bring offerings, and give thanks for the good in life.” Julián raises his hand and questions the conflicting ways of seeing development. “Development at what cost? We can’t compete with the way they see development, because what they see is money. We need to ask, what do we want in our villages?” Julián reminds us all that real wealth can be found in clean air, in a river full of fish. But he also speaks of something else: poverty. While it’s true that indigenous people want to protect their land and culture, Julián admits that inaction is not an option. There are families that can’t even fulfill their children’s basic needs: health, education and a balanced diet. But he also knows that won’t be achieved by destroying the world around them. “What if we were trained to use forests sustainably?” he suggests. The representatives of the lower basin, almost all Mexicaneros, agree with him. They want to learn how to use the resources available downstream to ensure steady work. Julián mentions something else that concerns us all: instability. He himself has been the victim of threats and harassment since he began opposing the dam. During a visit to Mexico, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders pointed out that indigenous activists and environmentalists are the most criminalized defenders. Their work is often related to large-scale mining, energy and infrastructure projects. Julián understands the situation of defenders throughout the region. He says that he doesn’t feel alone in the fight to protect the rivers, and he understands that risks are everywhere. “If they kill a defender in Colombia,” he says, “it harms us too.” Women and Mother Earth If the situation is complicated for indigenous men who seek to make their voices heard, it’s even more so for women who speak out in defense of their territory. Marcelina López, a Náyeri leader, speaks softly, glances down at her hands, and shares how difficult it’s been to fight for her community. Then, with a clear and strong voice, she explains, “The authorities treat me badly because I am indigenous and a woman. Of course, we are poor and indigenous; but we are rich because of Mother Earth.” Marcelina speaks of the little they have been consulted for development projects, of the purchase of consent through municipal services, and of the constant discourse that indigenous people don’t know how to see “beyond,” to see progress. “What they don’t understand is that we choose not to exploit some things because we are afraid of contaminating, and the river always comes first,” she explains. Gila de la Cruz, also Náyeri, timidly agrees with Marcelina. She tells us that, as a woman, she’s only been consulted on issues related to children. She says she has an opinion about the river, the services in her community, and the production of food; she mentions a drainage project that she and a large portion of her community disapprove of. She asks us not to misunderstand her, but she believes things shouldn’t happen just because they’ve always been done that way. She’s worried that they haven’t explained everything. “What happens after they put the tubes in? Where does the water go, to the river? Why can’t we reuse the water?” Gila’s complaint makes sense: the river could be at risk, the authorities don’t explain what they're doing, and then they scold her for questioning them. “There are other options, I've seen them,” she says. “There are ways to be more sustainable and not contaminate the water. " Angry now, she says that her opinions have not been heard because she is a woman. Why we must listen to indigenous voices All the representatives agree on one thing: they do not want to be seen as a closed opposition, without the desire to have a better life. They’re merely asking for dialogue. Among their activities as peasants, artisans and fishermen, they’ve made time to organize themselves, to learn about their rights, to master a language that is not their own, and take their concerns to the relevant institutions. They all agree that there are sustainable ways to better their quality of life without affecting the environment. Julián hopes that, ultimately, indigenous groups and authorities can reach a mutual understanding. “Can we all work together—organizations, governments and indigenous peoples? I think so,” he says. Julián asks for training; he wants to learn about infrastructure, and about a socially responsible economy. Gila and Marcelina have dedicated themselves to seeking more sustainable options to produce their food, to build something, to be healthy. "We just need to be taught," Gila says. Humanity is going through a period in which it's become necessary to question all our schemes: our ways of consumption, of using resources, of seeking comfort. Indigenous peoples have lived for centuries in a much more sustainable way than societies constructed under the ethos of the industrial revolution. They offer us, in many ways, examples and opportunities to learn again, to change and to improve. "One day there will be a public space where there is no fear, where I can say anything," Gila says. She speaks about progress made in recent years, noting that they’ve been slowly gaining space. "They should start listening to women,” she says. “They think we should be at home, but we’re here, organizing." Marcelina adds, with satisfaction, "This is how you feel when you’re fighting for your life.”

Read more

How Brazil is threatening indigenous and environmental rights

With the new presidency, Brazil has entered an unfortunate period of changes—to legislation, governmental structure, and foreign and public policy—that will set the nation back decades on the issues of climate, the environment and human rights. The new administration has made a host of extremely questionable decisions that signal the weakening of guarantees for indigenous peoples in Brazil, the Amazon, and the environment as a whole. Some of the reforms that most stand out include: The transfer of the Ministry of the Environment’s most important functions to the Ministry of Agriculture. The weakening of governmental entities responsible for monitoring cases of environmental crimes. The transfer of responsibility for demarcating indigenous lands from the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) to the Ministry of Agriculture. The suspension of contracts signed between state entities and civil society organizations. The weakening of the process for granting environmental permits. Continuous threats to withdraw Brazil from international agreements on the protection of the environment and indigenous peoples, including the recent threat to leave ILO Convention 169. These changes seem to be just the beginning, and the outlook could worsen at any moment. The latest move to undermine environmental protection in Brazil is the apparent opening of indigenous lands to large-scale mining projects. In March, Brazil’s Minister of Mines and Energy announced to attendees of one of the largest global mining events (the annual convention of the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada) that he would seek authorization for mining activities in indigenous and border areas. He stated that indigenous peoples would not have the autonomy to prevent the installation of mines in their territory. The State’s priority, this move implies, will be to promote irresponsible development over the protection of human rights. How mining threatens indigenous lands Last year, a government decree (Decree 9406) established drastic changes and new flexibility for mining activities, including successive extensions for permits in the event of lack of access, lack of consent or permission of the environmental agency, and the consideration that mining's foundations are the national interest and public utility. But mining itself is not in the national interest, since it implies great environmental damage and throws ecosystems out of balance. It must instead be recognized as a high-risk activity that causes destruction and contamination. Brazil has been incapable of safely regulating mining activities. We need only think of the rupture of two dams of mining waste in less than four years in the state of Minas Gerais. The first case in Mariana is considered the greatest environmental tragedy in Brazil’s history, and the second, earlier this year in Brumadinho, resulted in 197 deaths and 111 missing persons. If the government’s need for mining is undeniable, so is the need for stricter controls, the use of safer techniques, and a serious national assessment of the viability of each and every mine. Given the serious environmental damage associated with mining, its implementation on indigenous lands implies transferring those damages to a minority and vulnerable population that depends directly on the health of the environment for its physical and cultural survival. Indigenous communities have the constitutional right to be heard on projects that may affect them; some communities have even created protocols on how they want to be consulted. To build a mine against the will of a community is to violate their rights to life, to self-determination, to autonomy, to culture, to not being forcibly displaced, to benefit from their native territories, and to a healthy environment, among many others. The statements of the Minister of Mines and Energy represent a complete lack of commitment to the fundamental rights established in the Brazilian Constitution, as well as to internationally recognized human rights. They reveal a singular intention to appease investors, particularly the Canadian company behind the Belo Sun mining project, which seeks to mine indigenous lands already impacted by the construction of the Belo Monte Dam. In defense of indigenous peoples Mining on indigenous lands is not yet adequately regulated in Brazil. What the country needs is for Congress to approve a law that respects the fundamental rights of indigenous communities and protects their lands, while including communities in the process. The setbacks posed by the current administration have only strengthened the resistance of indigenous communities, and those of us who support them. Civil society organizations like AIDA are committed to defending human rights, safeguarding indigenous territory, and holding governments and corporations accountable whenever they pose a threat.

Read more

Statement on the Assassination of Dilma Ferreira Silva, leader of Brazil’s Movement of Dam-Affected Peoples

In the face of the brutal crime committed on March 22nd against a coordinator of the Movement of Dam-Affected Peoples in Brazil, the undersigned human rights and environmental organizations call on Brazilian authorities and multilateral organizations to ensure that the country’s obligations regarding the protection of human rights and environmental defenders are enforced. With deep sadness and indignation, we received the news that Dilma Ferreira Silva, a regional coordinator of Brazil’s Movement of Dam-Affected Peoples (MAB), together with her husband Claudionor Costa da Silva and Hilton Lopes, a friend of the family, were assassinated on Friday, March 22nd in the Amazonian state of Pará. The bodies of the three victims were found in her residence with signs of torture. Dilma Ferreira Silva was a prominent activist and recognized leader who, for more than three decades, fought for the rights of the people affected by the Tucuruí mega-hydroelectric dam project on the Tocantins River of the Brazilian Amazon, built during the country’s military dictatorship 1964-1985), provoking the displacement of an estimated 32,000 people, along with serious environmental damage. This is not the first case of a brutal murder perpetrated against a human rights defender in the region of the Tucurui dam. In April 2009, Raimundo Nonato do Carmo, a union leader who fought on behalf of those whose lives were ruined by the Tucuruí dam was shot seven times by two men on a motorcycle as he walked out of a supermarket on the street in which he lived in the town of Tucuruí. Dilma dedicated her life to promoting national policies that would effectively take into account the rights of dam-affected peoples, with due attention to gender issues that particularly affect the rights of women. Dilma Ferreira lived in the rural settlement of Salvador Allende, where land titles were issued for family farmers by the federal government in 2012, as a result of a popular mobilization of the Movement of the Landless Workers (MST), with support from MAB. However, the area continued to be coveted by land grabbers (grileiros) that invade and seize control of public and community lands. One such example is Fernando Ferreira Rosa Filho (aka ‘Fernandinho’) arrested by the civil police force of the state of Pará as the principal suspect in the triple homicide of Dilma Ferreira, Claudionor Costa da Silva and Hilton Lopes. The assassination of Dilma Ferreira Silva is evidence of the grave situation faced by human rights and environmental defenders in Brazil, a country that tops the global ranking in violence practiced against defenders, with one person murdered every six days in 2017. The incoming administration of President Jair Bolsonaro has intensified recent attempts to undermine Brazil’s progressive legislation on environmental protection and human rights - especially those of indigenous peoples, quilombolas (descendants of African slaves), family farmers and other traditional populations. Such attempts have often clashed with Brazil’s progressive Federal Constitution, approved in 1988 during a period of redemocratization that followed military rule. Backsliding on public policies, together with public statements that incite violence in conflictive areas, are seriously increasing the risks faced by human rights and environmental defenders such as Dilma Ferreira Silva. The undersigned human rights and environmental organizations express our solidarity with the family of Dilma and the Movement of Dam-Affected Peoples (MAB). Without a doubt, her assassination is a huge loss for the defense of the environment and human rights in the Amazon. We stand with the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights in demanding a complete, independent and imparcial investigation of the assassination of Dilma Ferreira Silva, as well as the exemplary punishment of those that carried out and ordered this horrendous crime. Moreover, we call on Brazilian authorities to ensure that the country’s domestic legislation and international obligations regarding the protection of human rights and environmental defenders are fully implemented, including preventative action to avoid further acts of violence. Signed, 1. 350.org 2. Aborigen-Forum 3. AMAR - Associação de Defesa do Meio Ambiente de Araucária 4. Amazon Watch 5. APREC Ecossistemas Costeiros 6. Arctic Consult 7. Articulação Antinuclear Brasileira 8. Asociación Interamericana para la Defensa del Ambiente - AIDA 9. Associação Mineira de Defesa do Ambiente – Amda 10. Association green alternative Georgia 11. Association of Journalists-Environmentalists of the Russian Union of Journalists 12. BAI Indigenous Women's Network in the Philippines 13. Bank Information Center (BIC) USA 14. Biodiversity Conservation Center 15. Both ENDS 16. Bretton Woods Project 17. Buryat Regional Association for Baikal 18. Business & Human Rights Center 19. Center for International Environmental Law - CIEL 20. CIDSE - International family of Catholic social justice organizations 21. Coalition for Human Rights in Development 22. Colegiado Mar RBMA/Reserva da Biosfera da Mata Atlântica - Grupo Conexão Abrolhos -Trindade 23. Coletivo de Mulheres do Xingu 24. Coletivo de Mulheres Negras de Altamira 25. Comisión Ecumenica de Derechos Humanos 26. Comité Ambiental en Defensa de la Vida 27. Conectas Direitos Humanos 28. Conseil Régional des Organisations Non Gouvernementales de Développement en RDC 29. Conselho Indigenista Missionário - CIMI 30. Corporación SOS Ambiental 31. Crescente Fértil 32. Derecho Ambiente y Recursos Naturales - DAR 33. Derechos Humanos y Medio Ambiente - DHUMA 34. Derechos Humanos y Medio Ambiente de Puno - Perú 35. DKA Austria 36. ECOA - Ecologia e Ação 37. Ecological Center DRONT 38. Ecolur Information NGO 39. Environmental Investigation Agency 40. Fastenopfer Switzerland 41. Focsiv - Federation of Italian Christian NGOs 42. Fórum em Defesa de Altamira 43. Foundation Sami Heritage and Development 44. Frente por uma Nova Política Energética para o Brasil 45. Front Line Defenders 46. Fundação Avina 47. Fundação Grupo ESQUEL 48. Future for Everyone 49. Global Witness 50. Green Dubna 51. Green Peace Brasil 52. ONG Guajiru 53. In Difesa Di - per i Diritti Umani e chi li difende 54. Indigenous Peoples Movement for Self-determination and Liberation (IPMSDL) 55. Instituto Igarapé 56. Instituto Terramar 57. Institutos Ethos 58. International Indigenous Fund for Development and Solidarity "Batani" dos EUA 59. International Land Coalition Secretariat 60. International Rivers 61. Katribu Kalipunan ng Katutubong Mamamayan ng Pilipinas (Katribu national alliance of indigenous peoples in the Philippines) 62. Kazan Federal University 63. Latin America Working Group 64. London Mining Network 65. Lumiere Synergie pour le Developpement 66. MAB - Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens 67. Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns 68. MISEREOR 69. Movimento Nacional de Luta pela Moradia (MNLM) 70. Movimento Negro 71. Movimento Paulo Jackson - Ética, Justiça, Cidadania 72. Movimento Tapajós Vivo 73. Movimento Xingu Vivo para Sempre 74. Movimiento de Afectados por Represas de America Latina - MAR 75. O Movimento Nacional das Cidadãs Posithivas (MNCP) 76. Oyu Tolgoi Watch 77. Pax Christi - Comisión Solidaridad Un Mundo Alemania 78. Pax Christi Internacional 79. Pax Christi Toronto 80. Projeto Saúde e Alegria 81. Protection International 82. Public Interest law Center (PILC/CHAD) 83. Red de Comités Ambientales del Tolima 84. Red de Género y Medio Ambiente de México 85. REDE GTA 86. Resource Rights Africa da Uganda 87. Rivers without Boundaries International Coalition 88. Rivers without Boundaries - Mongolia 89. SAPÊ - Sociedade Agrense de Proteção Ecológica 90. SCIAF - Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund 91. Serpaj Chile 92. Siberian Environmental Organization 93. Socio-ecological Union International 94. Tatarstan Organization of the All-Russian Society for the Conservation of Nature 95. Terra 1530 96. The Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace/Caritas 97. The Society for Threatened Peoples International STPI - Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker-International, GfbV-International 98. The Volunteer Movement Save Utrish 99. Toxisphera - Associação de Saúde Ambiental 100. Tutela Legal Maria Julia Hernández 101. Uma Gota no Oceano 102. Uniafro Brasil 103. Washington Office on Latin America - Wola 104. WoMin African Alliance 105. World Wide Fund for Nature – WWF/Brasil

Read more