Project

Preserving the legacy of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Heart of the World

Rising abruptly from Colombia’s Caribbean coast, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta reaches 5,775 meters (18,946 ft.) at its highest points, the peaks of Bolívar and Colón. It is the highest coastal mountain system in the world, a place where indigenous knowledge and nature’s own wisdom converge.

The sheer changes in elevation create a wide variety of ecosystems within a small area, where the diversity of plant and animal life creates a unique exuberant region. The melting snows of the highest peaks form rivers and lakes, whose freshwater flows down steep slopes to the tropical sea at the base of the mountains.

The indigenous Arhuaco, Kogi, Wiwa, and Kankuamo people protect and care for this natural treasure with an authority they have inherited from their ancestors. According to their worldview the land is sacred and shared in divine communion between humans, animals, plants, rivers, mountains, and the spirts of their ancestors.

Despite this ancestral inheritance, development projects proposed for the region have failed to take the opinions of these indigenous groups into consideration. The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is currently threatened by 251 mineral concessions, hydroelectric projects, agriculture, urban sprawl, and infrastructure projects.

Many of these concessions were granted without the prior consultation of the indigenous communities, which represents a persistent and systematic violation of their rights.

Mining, which implies the contamination and erosion of watersheds, threatens the health of more than 30 rivers that flow out of the Sierra; these are the water sources of the departments of Magdalena, César, and La Guajira.

These threats have brought this natural paradise to the brink of no return. With it, would go the traditional lives of its indigenous inhabitants, who are dependent on the health of their land and the sacred sites it contains.

The Sierra hosts the archaeological site of la Ciudad Perdida, the Lost City, known as Teyuna, the cradle of Tayrona civilization. According to tradition, it is the source from which all nature was born—the living heart of the world.

The four guardian cultures of the Sierra are uninterested in allowing this natural and cultural legacy to disappear.

Related projects

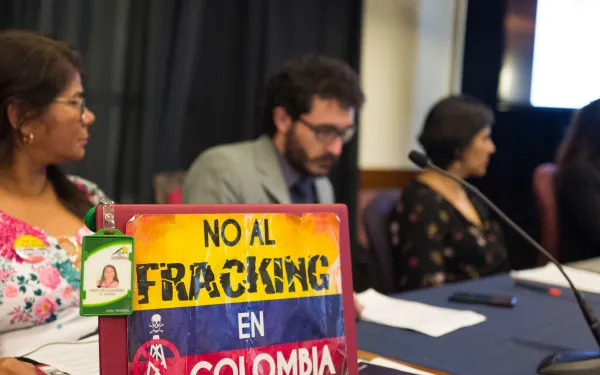

Civil society warns Inter-American Commission of human rights violations caused by fracking in Latin America

Boulder, Colorado. Representatives of communities and organizations from across Latin America testified before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights this week on the impacts that hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has on human rights and the environment. The hearing—responding to a petition signed by more than 126 organizations from 11 countries of the Americas—was held in Boulder, Colorado this week as part of the Commission’s 169th period of sessions. The principal requests to the Commission, and the Rapporteurs from various countries, were to urge the States to adopt efficient and opportune measures to prevent human rights violations resulting from the exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons, and to apply the precautionary principal in the face of fracking’s environmental damages. “In Latin America, fracking been carried out without informing or adequately consulting the affected populations, thereby violating their right to information, participation, prior consultation and consent,” explained Liliana Ávila, Senior Attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). “Fracking’s demand for water competes with the use of water for human consumption, and the contamination it causes in the water, soil and air seriously impacts the right to a healthy environment and compromises the effective enjoyment of other rights—including a dignified life, personal integrity, health, food, water and adequate housing.” At the hearing, it was emphasized that women disproportionately suffer the impacts of fracking due to potential harm to their reproductive health, and since women are traditionally responsible for collecting water for use in their homes. Referring to the experience of the Mapuche communities of Argentina, Santiago Cané of the Environment and Natural Resources Foundation (FARN) stressed, “Fracking produces acts of violence against those who defend the environment and their rights.” “Institutionally, we can talk about the criminalization of social protest as one form of intimidation to eliminate the resistance to fracking projects,” he explained. “The prosecution of criminal cases against communities leaders that oppose the development of fracking has become an institutional media campaign that seeks to promote the idea that Mapuche communities are part of a terrorist group.” In Mexico, “specifically in the municipality of Papantla, Veracruz—which according to freedom of information requests is the city with the greatest number of fracking pools in the country—where the population is primarily the Totonac people, this exploitation technique has led to the diversion of springs and the drying up of artisanal wells. Many communities have lost their natural sources of water and have seen their health compromised and their living conditions deteriorate,” explained Alejandra Jiménez of the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking. Dorys Gutiérrez, of the Colombian organization Corporation for the Defense of Water, Territory and Ecosystems, noted that: “In Europe, 18 nations have applied the precautionary principle to prohibit or restrict this practice and in Australia, four of the eight territories have bans or moratoria in place. If fracking is so beneficial, why has it been so widely rejected in so many places?” According to data compiled by the Latin American Alliance on Fracking, roughly 5,000 fracking wells exist across the region. About 2,000 of those wells are found in Argentina; more than 3,350 are found in Mexico; and in Chile, according to official data, 182 wells have been approved, primarily for the island of Tierra del Fuego. Despite the technique’s expansion across the region, there has also been progress in banning or imposing restrictions on fracking in three states of the United States, in Uruguay, in the Argentine province of Entre Ríos, and in more than 300 municipalities in Brazil. Fracking’s advance is harmful to human rights, and represents a threat to the consolidation of the legal framework promoted by the Inter-American Human Rights System, which includes the obligations of States and the international protection of human rights and the environment. PRESS CONTACTS: Victor Quintanilla (MExico), AIDA, [email protected], +521 5570522107 Arturo Contreras (in Boulder, Colorado), +521 5533320505

Read more

Say no to large dams: 3 reasons to opt for alternative energy sources

By Florencia Ortúzar and Monti Aguirre* Hydroelectric energy has been one of the largest drivers of development in many Latin American nations, and still represents a large portion of the region’s energy matrix. But is it really the best option? In response to a blog by the Inter-American Development Bank reflecting on the future of the hydroelectric sector in Latin America, we’d like to reflect on what it means to continue betting on large dams in Latin America. What follows are three reasons why we must say no to more large dams: 1. Better alternatives to hydroelectricity exist, and should be considered in project planning Before selecting an alternative energy source, governments and companies should develop a strategic plan that analyzes energy needs and the best way of achieving them. In this analysis, all options must be considered. It’s worrysome that this doesn’t already happen. For example, in the case of the Hidroituango dam—thought to be the largest in Colombia and associated with serious socio-environmental damages—the government decided to not conduct a prior evaluation of alternatives. Although the law did not require it at the time, the evaluation was recommended and is an international standard that large financial institutions should apply when investing in projects of this type. Today, other energy sources—like wind and solar—are proven to be economically competitive, can be constructed more quickly, and do not aggravate climate change. Innovations in smart grids, power storage and batteries also solve intermittency problems and make hydroelectric plants unnecessary. Geothermal, tidal, and wave energy are alternatives, the potential of which we have not even glimpsed. The promotion of large dams only delays adoption of the truly clean energy solutions that Latin America and the planet desperately need. According to the Bank’s own studies, Latin America has the largest quantity and most varied sources of renewable energy in the world. The region's renewable resources could provide almost seven times the installed capacity worldwide, excluding hydroelectric power. Therefore, although the region still holds great potential for untapped hydroelectric power, it’s necessary to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the situation, taking into account the costs and benefits as compared to other energy options. Only then can governments decide whether it’s worth continuing to invest in hydropower, or whether it’s better to opt for other types of energy—thus avoiding the social, environmental and financial impacts that come with large dams. 2. Large dams cause socio-environmental damage and are not profitable It has been demonstrated repeatedly that the socio-environmental impacts of hydroelectric plants are greater than initially considered. In addition to forced displacement and the criminalization of those who oppose them, large dams flood land, reduce river flows, and change the ecosystems of downstream wetlands, destroying habitats and contributing to species extinction. All this impacts the lives of nearby communities, limiting their ability to adapt to climate change. In economic terms, a study by the University of Oxford concluded that “even before accounting for the negative impacts on human society and environment, the actual construction costs of large dams are too high to yield a positive return.” In it, researchers show that the budgets and timeframes of large dam projects are consistently underestimated. Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam, for example, ran two times over its original budget, making it the most expensive public works project in the Amazon region. The budget of Chile’s Alto Maipo Dam has doubled four times over since the project was approved in 2009. Recognizing that the costs far outweigh the benefits, some countries have opted for dismantling large dams. And private companies have scrapped hydroelectric projects altogether because they are neither economically viable nor profitable. The United States government has adopted a policy to refuse any loan, donation, strategy or policy supporting the construction of large dams. 3. Large dams contribute to climate change Climate change must be considered when discussing the relevance of hydroelectricity. Reservoirs generate significant quantities of greenhouse gases, particularly methane, which is 30 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide. Likewise, the construction of dams endangers valuable carbon sinks like rivers and forests. For that reason, a proper analysis of carbon dioxide and methane emissions should be conducted before choosing a dam project—a process that usually doesn't occur. Another aspect to consider is the vulnerability of dams to climate variations. Extreme rainfall increases sedimentation, which can cause structural problems and reduce the dam's lifespan. Droughts, now increasingly frequent, can render dams inefficient. As more dams lose efficiency, Latin America—now highly dependent on hydroelectricity—will be more vulnerable to energy shortages. Even more serious is the threat posed by large dams in extreme weather events. In a dam gave way during bad weather, erasing entire villages. In Laos earlier this year, mass evacuations were ordered after heavy rains threatened a dam collapse. In Kerala, India, torrential rains, coupled with the mismanagement of several dams, have caused unprecedented flooding. In certain countries, the risk of dams overflowing or collapsing has already been recognized as a serious problem. Over time, more hydroelectric plants will begin to deteriorate and will require large investments to safeguard the communities living downstream. As civil society representatives working for a more just and sustainable Latin America, we urge financial institutions like the Inter-American Development Bank to support the change we as a region need. We call on them to stop investing in large dams, which have been demonstrated time and again to be dangerous to the environment and local communities, costly for countries, and unsuited for our rapidly changing climate. It’s time for a better energy plan. And it’s time to invest in non-conventional renewable energy based on thorough, independent and high-quality social and environmental impact assessments, the planning and implementation of which respect human rights. * Monti Aguirre is the Latin America Program Coordinator for International Rivers.

Read more

Inter-American Commission to analyze fracking’s impacts on human rights

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights will hold an informative hearing on October 3, 2018 to better understand the situation of fracking in the Americas and the human rights violations it’s causing. The hearing is being held in response to a request brought forth by 126 Latin American organizations, united in the Latin American Alliance on Fracking. The hearing will take place in Boulder, Colorado during the Commission’s 169th period of sessions. In it, human rights defenders and representatives of affected communities will present detailed information on the documented human rights impacts, as well as the potential risks, of fracking in Latin America. The Alliance seeks to propose a series of recommendations to the Commission and governments of the region in order to guarantee human rights when faced with the exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbon reserves. According to the hearing request, there are approximately 5,000 fracking wells throughout Latin America. In Argentina, there are roughly 2,000 wells. In Chile, according to official data, 182 wells have been approved, the large majority in Tierra del Fuego. In Mexico, there are more than 3,350 fracking wells, although the signatory organizations indicated there are challenges in terms of access to this information. In Brazil and Colombia, contracts have been signed that allow for exploration and exploitation. In Bolivia, prospecting and sample studies of unconventional deposits have begun. Organizations from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay signed the request for a hearing before the Commission in July. “Fracking’s advance in Latin America is being carried out blindly because neither the chemicals used, nor their synergistic effects, nor the actual and potential risks, nor the effectiveness of mitigation measures are known with any certainty,” explained Claudia Velarde, attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). “What is known is the damage fracking causes to the environment, the quantity and quality of water, and the impacts it has on health and human rights.” While fracking is promoted across Latin America, various nations, states and provinces of Europe, the Americas and Oceania have banned the technique due to the negative impacts it has had on the environment and public health. The request to the Commission emphasizes, “none of the nations where fracking has been implemented have a comprehensive knowledge of the irreversible damage it causes to the environment and the lives of individuals and communities. However, abundant scientific evidence exists on fracking’s negative impacts due to the extensive use of the technique in the United States.” Follow news from the hearing with the hashtag #AméricaSinFracking PRESS CONTACT Victor Quintanilla, AIDA (Mexico), [email protected], +521 5570522107

Read more