Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

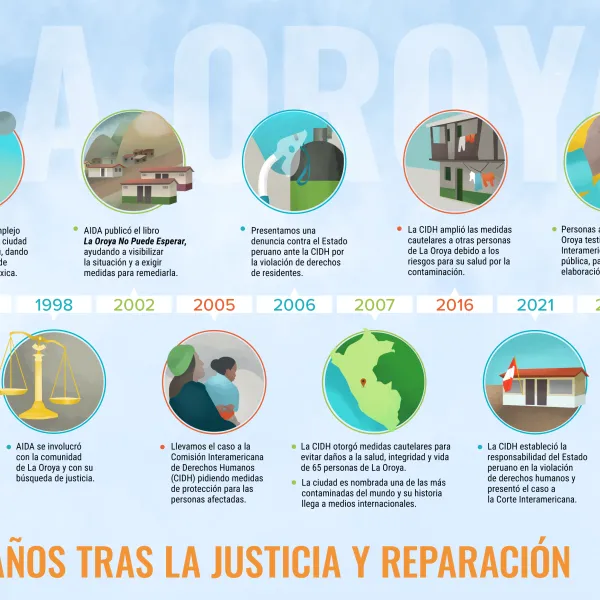

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

The role of critical minerals in the energy transition: policy implications at the local, national, regional and global level

2023 was the hottest year: 1.45 ºC above pre-industrial values. The trend points to an increase of 3º C. Consequently, climate events are becoming more extreme, frequent and long-lasting, affecting particularly vulnerable populations in the Global South. These countries not only lack financing to face losses and damages, and to propose mitigation and adaptation measures, but also bear the brunt of increased extraction of minerals needed for the energy transition in the Global North. The G20 countries, responsible for 76% of GHG emissions, should lead ambitious climate action, particularly in the energy sector, which accounts for 86% of global CO2 emissions (UNEP, 2023).In the outline of plans and policies for the energy transition, the demand for minerals considered critical, such as lithium, is increasing rapidly, exacerbating the global climate and ecological crisis by threatening Andean wetlands´ contribution to climate adaptation and mitigation. Also, this pressure to extract is affecting the rights of the indigenous communities who inhabit the salt flats in Argentina, Chile and Bolivia, which together concentrate over 50% of the world’s reserves. Additionally, geopolitical competition for technological control of the energy transition hinders countries in the region from advancing in the battery production value chain. Tensions emerge between technicaleconomic positions that prioritize the security of supply and friend-shoring and those that integrate the relationship between energy, ecological and socio-economic systems and challenge power asymmetries.This policy brief discusses lithium´s challenges for energy transition debates and calls the G-20 to ensure commitment to improved global cooperation that involves material reduction targets in the Global North, benefits for producer countries and a strong respect for planetary boundaries and human rights. Read and download the policy brief

Read more

COP29: Climate target disappoints and invites us to look elsewhere for hope

The twenty-ninth United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29), held in Baku, Azerbaijan, was dubbed "the COP of finance" because the most anticipated decision was the establishment of the New Collective and Quantifiable Global Climate Finance Goal (NCQG), the amount that developed countries would pledge to finance climate action in developing countries. This issue grabbed all the attention, overshadowing everything else.In addition, the recent re-election of Donald Trump as President of the United States, accompanied by his threat to abandon the Paris Agreement and reverse the country's climate action, set the tone for the event.The negotiations, which took place from November 11 to 22, were intense and ended almost two full days late, with the approval of a text that caused great disappointment.However, the invitation is not to be blinded by disappointment. As much as we want, demand and hope, the international climate negotiations are not delivering what we so desperately need. Let us look for hope in what is happening and working, such as local, community-led projects and the work of civil society that is not giving up.Here is a review of COP29 based on what was agreed on climate finance and other relevant issues. A new climate finance targetThe mandate was clear: the new target should exceed the previous one of $100 billion per year and respond to the needs and priorities of developing countries. But while developing countries demanded $1.3 trillion per year, the offer was a mere $300 billion (less than a third and just 12% of the global military budget in 2023) by 2035. "Is this a joke?" exclaimed the head of the Bolivian delegation at a press conference.Developing countries also demanded that financing be adequate, i.e. based mainly on public resources, in the form of grants and highly concessional instruments that would not add to the heavy debts they already carry. They also called for the explicit inclusion of loss and damage as one of the objectives of financing (along with mitigation and adaptation), as well as a specific target for adaptation.None of this was achieved. The target was left open to private financing, further diluting the responsibility of developed countries. There was no specific target for adaptation, nor was there any mention of loss and damage. In case there was any doubt, all references to human rights were removed from the final text.The only saving grace was a call to mobilize $1.3 trillion in climate finance annually from a broad base of sources through the so-called Baku-Belem Roadmap, with a view to achieving this goal by 2035. However, this is a "call" and not a binding commitment, the concrete results of which will depend on political will in the coming years. Global stocktaking and gender issuesNo significant progress was made on the results of last year's Global Stocktaking on the implementation of the Paris Agreement, particularly on the transition away from fossil fuels. The issue was deferred to COP30, which will be held next year in the Brazilian city of Belém do Pará.While there has also been insufficient progress on gender issues, some progress should be recognized, such as the extension of the Lima Work Program to 10 years, which lays the groundwork for the development of a Gender Action Plan and provides an opportunity to further deepen the integration of gender into climate action, particularly as countries develop updates to their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).In addition, the text of the NCQG recognizes women as beneficiaries of funds but fails to ensure that the specific circumstances and intersectional discrimination that many women face are addressed. Carbon marketsWhat did see advances during the negotiations were carbon markets, with the approval of the rules for a global market. Carbon markets are trading systems where carbon credits are bought and sold. Each credit represents one ton of CO₂, or its equivalent in other greenhouse gases, removed from the atmosphere. The credits are generated by projects that reduce emissions (such as forest conservation, renewable energy, or energy efficiency). The buyers are polluting companies that want to offset their emissions in order to remain in compliance.The issue has been under discussion for more than a decade due to the difficulty of ensuring the credibility of the system to reduce emissions. Although it is the last outstanding issue of the Paris Agreement, signed more than 10 years ago, civil society is not celebrating. These markets allow companies to continue polluting if they pay for carbon reductions elsewhere in the world. Methane emission reductionsA promising development was the signing of the Declaration on Methane Reduction from Organic Waste by more than 30 countries. The signatories, representing nearly half of global emissions, committed to setting sector-specific methane reduction targets in their future NDCs, underscoring the importance of organic waste management in the fight against climate change. Closing thoughtsIn the end, the results are not surprising. Conventions on climate change are often not much to celebrate, but we must not forget that they are a unique space where all countries sit down to seek consensus to advance a common goal. Its very existence reflects an intention to acknowledge historical responsibilities in favor of justice and a world where we can live together in harmony. It is a platform from which to push, even if it brings more frustration than results.On the other hand, it is very encouraging and motivating to see civil society in action. Hundreds of representatives from different organizations and movements are doing their best to achieve results that reflect the fulfillment of international commitments of developed countries towards their developing counterparts, the climate and the natural balance of our planet.Finally, the side events that take place parallel to the negotiations are a source of inspiration. On the sidelines, without much fanfare, there are people from communities and indigenous peoples who are implementing climate solutions in their territories, with concrete, successful results. These people, like seeds silently germinating, are a powerful source of hope.

Read more

The ABCs of "critical" or transition minerals and their role in energy production

By Mayela Sánchez, David Cañas and Javier Oviedo* There is no doubt that we need to move away from fossil fuels to address the climate crisis. But what does it mean to switch to other energy sources?To make a battery or a solar panel, raw materials from nature are also used.Some of these raw materials are minerals which, due to their characteristics and in the context of the energy transition, have been descriptively named "critical" minerals or transition minerals.What are these minerals, where are they found, and how are they used?Below we answer the most important questions about these mineral resources, because it is crucial to know which natural resources will supply the new energy sources, and to ensure that their extraction respects human rights and planetary limits, so that the energy transition is just. What are "critical" or transition minerals and why are they called that?They are a group of minerals with a high capacity to store and conduct energy. Because of these properties, they are used in the development of renewable energy technologies, such as solar panels, batteries for electric mobility, or wind turbines.They are so called because they are considered strategic to the energy transition. The term "critical" refers to elements that are vital to the economy and national security, but whose supply chain is vulnerable to disruption. This means that transition minerals may be strategic minerals, but not critical in terms of security and the economy.However, given the urgency of climate action, some states and international organizations have classified transition minerals as "critical" minerals in order to promote and facilitate access to these raw materials.They are also often referred to as transition minerals because they are considered essential for the technological development of renewable energy sources, such as those mentioned above. And in the context of the energy transition, energy sources that use these minerals are the most sought-after to replace fossil energy sources. What are the most important "critical" or transition minerals?The most important transition minerals are cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium, nickel and rare earth.But there are at least 19 minerals used in various renewable energy technologies: bauxite, cadmium, cobalt, copper, chromium, tin, gallium, germanium, graphite, indium, lithium, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, selenium, silicon, tellurium, titanium, zinc, and the "rare" earth. What are "rare" earth elements and why are they so called?The "rare" earth elements are the 16 chemical elements of the lanthanoid or lanthanide group, plus Ithrium (Y), whose chemical behavior is virtually the same as that of the lanthanoids.They are Scandium, Ithrium, Lanthanum, Cerium, Praseodymium, Neodymium, Samarium, Europium, Gadolinium, Terbium, Dysprosium, Holmium, Erbium, Tullium, Iterbium and Lutetium.They are so called because when they were discovered in the 18th and 19th centuries, they were less well known than other elements considered similar, such as calcium. But the name is now outdated.Nor does the term "rare" refer to their abundance, because although they are not usually concentrated in deposits that can be exploited (so their mines are few), even the less abundant elements in this group are much more common than gold. What are "critical" or transition minerals used for? What technologies are based on them?The uses of transition minerals in the technological development of renewable energy sources are diverse:Solar technologies: bauxite, cadmium, tin, germanium, gallium, indium, selenium, silicon, tellurium, zinc.Electrical installations: copper.Wind energy: bauxite, copper, chromium, manganese, molybdenum, rare earths, zinc.Energy storage: bauxite, cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, rare earths, titanium.Batteries: cobalt, graphite, lithium, manganese, nickel, rare earths. In addition, they are used in a variety of modern technologies, for example in the manufacture of displays, cell phones, computer hard drives and LED lights, among others. Where are "critical" or transition minerals found?The geography of transition minerals is broad, ranging from China to Canada, from the United States to Australia. But their extraction has been concentrated in countries of the global south.Several Latin American countries are among the top producers of various transition minerals. These materials are found in complex areas rich in biological and cultural diversity, such as the Amazon and the Andean wetlands.Argentina: lithiumBrazil: aluminum, bauxite, lithium, manganese, rare earths, titaniumBolivia: lithiumChile: copper, lithium, molybdenumColombia: nickelMexico: copper, tin, molybdenum, zincPeru: tin, molybdenum, zinc How do "critical" or transition minerals support the energy transition and decarbonization?Transition minerals are seen as indispensable links in the energy transition to decarbonization, i.e. the shift away from fossil energy sources.But the global interest in these materials also raises questions about the benefits and challenges of mining transition minerals.The issue has become so relevant that last September, the United Nations Panel on Critical Minerals for Energy Transition issued a set of recommendations and principles to ensure equitable, fair and sustainable management of these minerals.In addition, as a result of the intensification and expansion of their extraction in countries of the region, the issue was brought before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights for the first time on November 15.In a public hearing, representatives of communities and organizations from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Colombia, as well as regional organizations, presented information and testimonies on the environmental and social impacts of transition mineral mining.Given the current energy transition process, it is necessary to know where the resources that will enable the technologies to achieve this transition will come from.The extraction and use of transition minerals must avoid imposing disproportionate environmental and social costs on local communities and ecosystems. *Mayela Sánchez is a digital community specialist at AIDA; David Cañas and Javier Oviedo are scientific advisors.Sources consulted:-Olivera, B., Tornel, C., Azamar, A., Minerales críticos para la transición energética. Conflictos y alternativas hacia una transformación socioecológica, Heinrich Böll Foundation Mexico City/Engenera/UAM-Unidad Xochimilco.-Science History Institute Museum & Library, “History and Future of Rare Earth Elements”.-FIMA NGO, Narratives on the extraction of critical minerals for the energy transition: Critiques from environmental and territorial justice.-Haxel, Hedrick & Orris, “Rare Earth-Elements. Critical Resources for High Technology,” 2005.-USGS 2014, “The Rare-Earth elements. Vital to modern technology and lifestyle”, 2014.-Final Report for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) Thematic Hearing: Minerals for Energy Transition and its Impact on Human Rights in the Americas, 2024.

Read more