Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

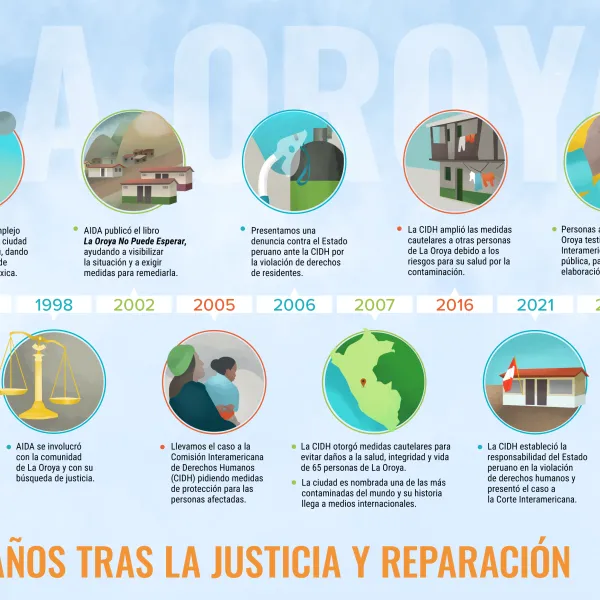

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Mexico Threatens to Dam a River of Life

Every June 24, the Cora indigenous community celebrates the Day of San Juan. Gathering on the banks of a full-flowing river in western Mexico, they swap figures of the saint and offer him flowers in exchange for food, health, work and other favors. They also pay respect to San Pedro Mezquital, a river that is critical to their culture, livelihoods and spirituality. San Pedro Mezquital is the only dam-free river left in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains where the Cora live. Starting in Durango, the river flows freely to the Pacific Ocean, where it feeds the Marismas Nacionales, a wetland of international importance and home to 20% of Mexico’s mangroves. But the river could be destroyed. Mexico’s state power company, the Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE), wants to dam the San Pedro Mezquital to produce electricity, a project that would harm the environment and the human rights of indigenous people in the area, including the Cora. AIDA wants to stop this. We are working with local organizations and scientists to prepare a legal case based on environmental and human rights arguments. The aim is to deter the Mexican government from approving the environmental impact assessment (EIA) that would allow the CFE to start building the Las Cruces hydropower project. We have also launched a national campaign to raise awareness on why Las Cruces should never be built, with a website (in Spanish) focused exclusively on the issue. Arguments Against Las Cruces Dam Here are a few of the arguments against Las Cruces: Blocking the natural flow of the river will increase sedimentation and damage the mangroves of Marismas Nacionales. The project’s EIA fails to evaluate the cumulative environmental impacts and doesn’t use the best available scientific information. Construction of the dam will forcibly displace people and communities, possibly without compensation. The latter is not mentioned in the EIA. Indigenous peoples were not consulted on the feasibility studies of the project or its construction. Reduced river flow will affect the daily activities (agriculture, livestock, fishing, oysters, etc.) that provide food and work for the surrounding communities. Ceremonial locations will be flooded, destroying significant aspects of the spiritual life and ancient cultures of the natives in the area. On any given day, Coras and other local people jump into the San Pedro Mezquital for a swim in waters that provide a refreshing break – and their livelihoods. With your help, we can keep this and other rivers from getting destroyed by large dams like Las Cruces! Thank you!

Read more

Air pollution in Latin America and its effect on our health and climate

By Héctor Herrera, AIDA legal advisor and coordinator of the Network for Environmental Justice in Colombia, @RJAColombia According to the latest report from the Clean Air Institute, Monterrey, Guadalajara and Mexico City (Mexico), Cochabamba (Bolivia), Santiago (Chile), Lima (Peru), Bogota and Medellin (Colombia), Montevideo (Uruguay) and San Salvador (El Salvador) are 10 most polluted cities in Latin America. In all of them, the level of air pollution exceeds World Health Organization recommendations. The scene is similar in big cities across the region: buses and trucks spew out black smoke as people walk under grey skies. This is the backdrop in The Sound of Things Falling, an award-winning novel by Colombia’s Juan Gabriel Vásquez in which descriptions like this abound: “On the corner of Carrera Cuarta, the heavy afternoon traffic was moving slowly, in single file, toward the exit on to Avenida Jiménez. I found the gap in the traffic I needed to cross in front of a small bus whose recently illuminated headlights were catching the dust from the street, the smoke from exhaust pipes and the beginnings of a light drizzle.” Vásquez is writing about Bogota. But he could just as easily have been describing Monterrey or San Salvador. Residents of Latin America’s big cities live enveloped in smog. They breathe in the microparticles of black carbon, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide that comes with the air polluted by urban transport, industry and power plants. We can get riled up when a passing truck spits a cloud of smoke in our face. But our outrage fades almost as soon when we think that making these vehicles more environmentally friendly is not our responsibility. Those decisions lie out of our reach in the hands of politicians and bureaucrats. Even so, we must understand that air pollution is a problem that affects all of us and so it is important to be aware of the associated health risks. THE Clean Air Institute's report explains how breathing in air containing a high concentration of pollutants can reduce our quality of life and lead to illness or premature death. Thankfully, the report also makes recommendations on how to avoid this. Worryingly, public health is not the only casualty of air pollution. Another is a faster pace of climate change Black carbon and ozone are short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) that remain in the atmosphere from days to decades. While that is nothing compared with carbon dioxide, which remains in the atmosphere for more than a century, SLCPs contribute more to climate change than carbon dioxide. This means that if we were to significantly reduce SLCP emissions, we would get quick results in slowing climate change. You can find more information on AIDA’s page on SLCPs, including descriptions of the main pollutants and the steps being taken to encourage a reduction in their emission. All of what has been said here becomes particularly pertinent when you consider that the population and number of vehicles in Latin America is growing steadily, which unfortunately is not the case for the number of measures being introduced to reduce the level of air pollutants. Whatever our motives – whether this is to improve public health, slow climate change, protect our lungs or those of future generations, or even to simply enjoy a picturesque sunset without a wall of harmful gases blocking our view of the sea or the mountains, one thing is imperative. We must work so that the air in our cities across the Americas is clean and fresh.

Read moreGroups appeal to UN to halt imminent forced evictions of indigenous Ngöbe families

Appeal to the UN seeks to stop eviction of Panamanian community. Panama, Washington D.C., San Francisco, Lima. Environmental and human rights organizations submitted an urgent appeal to United Nations Special Rapporteurs on behalf of members of the indigenous Ngöbe community - the community faces imminent forced eviction from their land for the Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam project in western Panama. The eviction would force Ngöbe communities from their land, which provides their primary sources of food and water, means of subsistence, and culture. The urgent appeal, submitted by the Ngöbe organization Movimiento 10 de Abril para la Defensa del Rio Tabasará (M10) and three international NGOs, the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), and Earthjustice, asks the Special Rapporteurs to call upon the State of Panama to suspend the eviction process and dam construction until it complies with its obligations under international law. Given that the project is financed by the German and Dutch development banks (DEG and FMO, respectively) and the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI), the groups also urge the Special Rapporteurs to call on Germany, the Netherlands, and the member States of CABEI to suspend financing until each country has taken measures to remedy and prevent further violations of the Ngöbe's human rights. The forced evictions of the Ngöbe are the most recent threat arising from the Barro Blanco project. These evictions raise imminent violations of their human rights to adequate housing; property, including free, prior and informed consent; food, water and means of subsistence; culture; and education. "Our lands and natural resources are the most important aspects of our culture. Every day, we fear we will be forced from our home,"said Weni Bagama of the M10. The appeal highlights the fact that the Ngöbe were never consulted, nor gave consent to leave their land. "Panama must respect the rights of the Ngöbe indigenous peoples and refrain from evicting them. Executing these forced evictions will constitute a violation of international human rights law," said María José Veramendi Villa of AIDA. Also central to the appeal is the role of governments whose banks are funding the dam. "Under international law, States must ensure that their development banks do not finance projects that violate human rights, including extraterritorially. Forced eviction of the Ngöbe without their consent is reason enough to suspend financing of this project," said Abby Rubinson of Earthjustice. Barro Blanco's registration under the Kyoto Protocol's Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is another point of concern. "Panama's failure to protect the Ngöbe from being forcibly displaced from their land without their consent casts serious doubt on the CDM's ability to ensure respect for human rights under international law," said Alyssa Johl of CIEL. "CDM projects must be designed and implemented in a manner that respects human rights obligations."

Read more