Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

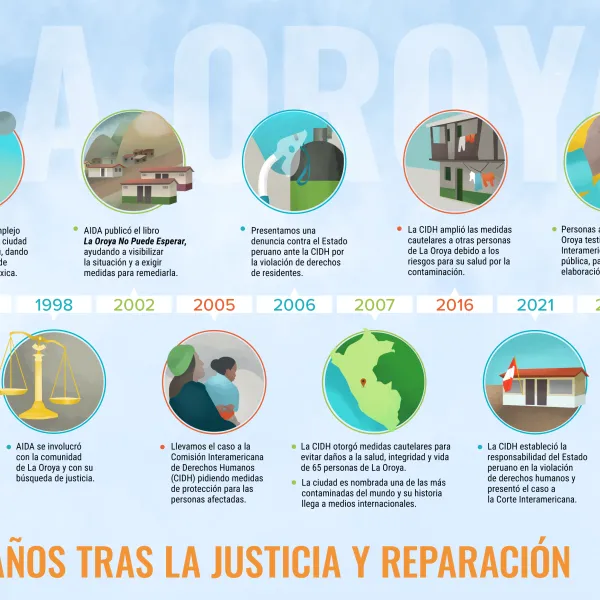

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Lives of no return: Stories behind the construction of Belo Monte

By María José Veramendi Villa, senior attorney, AIDA, @MaJoVeramendi When you start the descent by plane to the city of Altamira in Pará, Brazil, the darkness of the night is interrupted by the bright lights of worksites a few kilometers outside the city where construction of the Belo Monte dam is underway. That’s when things turn bleak. On a recent trip to the area I was able to see how the situation of thousands of residents – the indigenous, riverine and city dwellers of Altamira - continues to deteriorate. Their communities and livelihoods are being irreversibly affected and their human rights systematically violated by the construction of the hydropower plant. When night becomes day From the plane, the lights from the worksites are just momentary flashes. But for the indigenous and riverine communities closest to them, those lights have brought a radical change to their lifestyles. José Alexandre lives with his family in Arroz Cru, a waterfront community located on the left bank of the Volta Grande, or Big Bend, of the Xingu River in the municipality of Vitória do Xingu. The community is in front of the Pimental worksite. His entire life has been spent in the area, where hunting and fishing are major activities. But everything changed when construction of the dam started.

Read more

The link between international environmental law, human rights and large dams

The article is an update and reissue of two chapters of the report Large Dams in the Americas: Is the Cure Worse than the Disease, written by Jacob Kopas and Astrid Puentes Riaño. The article identifies “the main obligations, standards, decisions and international law applicable to large hydropower plants that our governments should use in the planning, implementation, operation and closure of these projects." The article is divided into two parts. Chapter I offers an overview of the main standards, the legal framework of international human rights and environmental law as well as the decisions and international jurisprudence applicable to the cases of large dams. In Chapter II, this framework is applied to the cases of human rights abuses caused by the degradation of the environment through the development of a large dam.

Read more

Short-Lived Climate Pollutants: A great opportunity to put the brakes on climate change

By Florencia Ortuzar, legal advisor, AIDA While many of us are alarmed by climate change and its already tangible effects, concern becomes even greater when learning the fact that all the CO2 accumulated in the atmosphere cannot be removed, even if we were to shut down all the sources of emissions today. This reality was confirmed in the Fifth Assessment Report on the state of the climate, issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The explanation for this is simple: CO2, in contrast to other gases and pollutants, remains in the atmosphere for millennia after being released. It is stuck in the atmosphere for what is eternal for human standards, implying that its greenhouse effect does not end even with an immediate halt in emissions. The good news is that CO2 is not the only cause of global warming. There are other pollutants that, unlike CO2, only stay in the atmosphere for a relatively short time. These “other” agents are responsible for 40-45% of global warming, and they remain in the atmosphere for a minimum of a few hours to a maximum of a few decades. They are called short-lived climate pollutants, or SLCPs. Like CO2, SLCP emissions have a negative impact on humans and ecosystems. So a reduction in these pollutants would bring immediate relief to the worst affected by climate change and would bring important benefits to the environment and people. The main SLCPs Although all SLCPs contribute significantly to climate change and share the trait of being short-lived, each has its unique characteristics and emission sources. Black carbon or soot, is a particulate substance produced by the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, mainly from motor vehicles, domestic stoves, fires and factories. The dark particles heat the atmosphere as they absorb light, and when the particles land on snow and ice they accelerate melting. Black carbon also affects human health by causing respiratory problems such as lung cancer and asthma. Tropospheric ozone is a gas formed by the reaction of the sun with other gases called "precursors," which can be man made or naturally occurring. One of these precursors is methane, another SLCP. Tropospheric ozone is associated with diseases including bronchitis, emphysema, asthma and permanent scarring of the lung tissue. Studies also show that this gas has a direct impact on vegetation, reducing crop yields and the ability of plants to absorb CO2. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, and 60% of its emissions come from human activities like rice farming, coal mining, landfill and oil combustion. Two important sources of methane include cattle farming, whose effect has dangerously increased with industrial meat production (Spanish), and large dams, especially those in tropical areas. Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are man-made gases used in the production of air conditioners, refrigerators and aerosols. They have replaced chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were banned under the Montreal Protocol. Although HFCs represent a small proportion of the greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere, their use is growing at an alarming speed of an average of 10-15% each year, according to a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report. Everyone wins According to the IPCC, the reduction of these pollutants could avert a rise in average global temperatures by approximately 0.5 degrees Celsius by 2050, cutting the current rate of global warming in half and helping to protect some of the areas most susceptible to climate change like the Arctic, the high Himalayan regions and Tibet. The mitigation of SLCPs is also crucial for decelerating glacial melting and rising sea levels, a serious situation for the world’s population that lives in coastal areas. The reduction of SLCPs would also bring important socio-environmental benefits. Black carbon and tropospheric ozone harm human health and reduce crop yields. This in turn affects ecosystems, food security, human welfare and the entire natural cycle that keeps the planet healthy. Some talking points Given that SLCPs stem from different sources, effective mitigation requires a series of comprehensive actions that deal with each pollutant separately. Fortunately, the road is already laid out. Many of the technologies, laws and institutions needed to cut SLCP emissions already exist. In the case of black carbon, new technologies are inexpensive and available. Developed countries have already reduced emissions significantly through the use of green technologies. Ideas include the modernization of domestic cooking systems in the region, introducing the use of solar cookers and new transport systems with improved exhaust filters to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The amount of methane in the atmosphere, which affects the level of tropospheric ozone, is largely dependent on industrial activities. To reduce emissions, effective regulations should be implemented to control the industries that emit the most methane, including intensive cattle farming, mining, hydrocarbons and large dams. For HFCs, an alternative already exists. There need to be regulations that encourage people to substitute HFCs for greener alternatives, no matter the commercial barriers. Some countries have proposed incorporating HFCs in the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement recognized as one of the most successful initiatives to significantly and rapidly reduce CFC emissions, addressing a similar challenge, to the one we face today. To find out more about SLCPs, you can read a briefing paper (Spanish) put together by AIDA, CEDHA, CEMDA and RedRacc.

Read more