Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

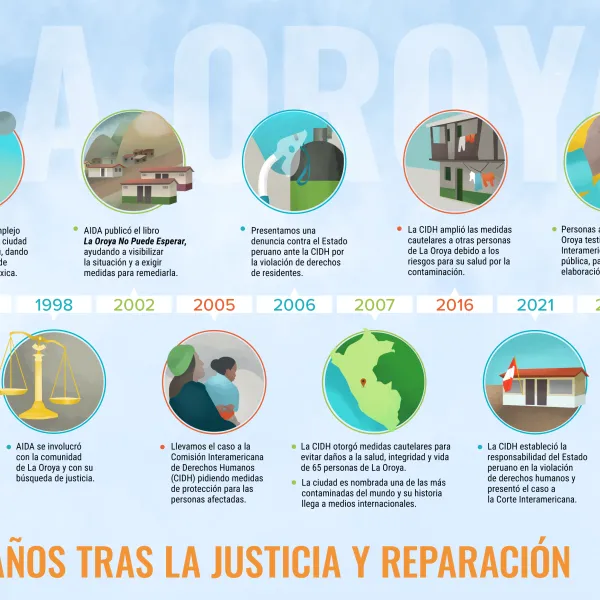

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Report from COP19: Warsaw, Poland

A terrifying nightmare came true before their eyes. Waves of up to seven meters (23 feet), propelled by winds that reached 315 kilometers per hour (196 miles per hour), caught the inhabitants of the Philippines off guard, devouring everything in their path. Typhoon Haiyan was the most devastating of the climate shocks that frequently hit the Asian country. “We can stop this madness.” With those words, Yeb Saño, the Philippine’s climate change commissioner, demanded “climate justice“ for his people during the inauguration of the 19th Conference of the Parties (COP19) on climate change in Warsaw, Poland. The tragedy was palpable in his eyes and voice. The effects of climate change are unmistakable. Ocean levels and temperatures are rising, and this is provoking storms surges of such intensity that they’re impossible to ignore. No more time can be wasted in coming up with the financing needed to fight this problem. And we must set the rules for the effective use of these funds. AIDA is pushing for this. At the COP19, we worked with other civil society organizations to encourage the governments of developing countries to draft an action plan next year designed to fulfill a vital commitment: making US$100 billion available to developing countries from 2020 for fighting climate change. Part of these funds will be channeled through the Green Climate Fund (GCF). AIDA has assisted in putting pressure on the governments of developed countries to provide certainty about the contributions they will make to this financing mechanism. We also have taken part in the creation of GCF by participating at meetings of its Board of Directors. Our short-term goal is to ensure that the role of civil society is effective and meaningful in the GCF decision-making process. Long term, we want the GCF to support effective actions for climate change mitigation and adaptation that will not only help reduce emissions but also benefit the most vulnerable communities that already are being affected by the phenomenon. Our presence at the COP19 also made it possible for AIDA to form alliances with groups from different sectors – civil society, youth, indigenous peoples, among others – in order to develop and strengthen a joint position ahead of the COP20 to be held in Peru. We hope that the COP20 will set the foundation for a new and hopefully successful climate agreement at the COP21 in Paris. We also worked with partner organizations to develop a briefing paper (in Spanish) on short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs), which we distributed in Warsaw. As SLCPs remain in the atmosphere less time than CO2, reducing these contaminants is a valuable opportunity for a short-term solution to global warming and an important element that should enter into the new climate agreement. With your support we will continue fighting to prevent typhoons and other natural disasters from becoming a way of life.

Read more

Latin America and its little-known biodiversity

By Tania Paz, general assistant, AIDA, @TaniaNinoshka Latin America and the Caribbean stretches over more than two billion hectares, or about 15% of the earth’s total land surface area. The region possesses the richest persity of species and ecoregions in the world. It is home to one third of the world’s renewable water resources and close to 30% of the world’s total runoff, or the free flow of surface water into a drainage basin, according to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2002). Even so, there are still many ecosystems that we don’t know much about despite their important role in maintaining the health and wellbeing of the environment and human society. These include mangrove forests, glaciers and páramos. Mangroves According to Mexico’s National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biopersity (CONABIO, in Spanish), mangroves are plant formations grouped into a distinct biome known as mangal, or a tree or shrub with branches that reach down and take root in the ground. They are a unique plant species for their resistance to salt and for growing in tropical coastal environments near estuaries and coastal lagoons. They are the transition between terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Mangrove forests form a natural protective barrier that prevents wind and tide erosion. They play an important role in the environment by filtering water and allowing it to flow into underground aquifers, and they act as carbon sinks that helpmitigate the effects of climate change. The major threats to mangrove ecosystems stem from urban, industrial, tourism and agricultural development given that they compete for land with these fragile ecosystems and cause heavy pollution. This is happening in Marismas Nacionales and Laguna Huizache-Caimanero, where a mega-tourism resort is threatening a wetland ecosystem that protects Mexico’s last remaining mangrove forests and 60 endangered species. Páramos Páramos (in Spanish) are wetlands found between 2,500 and 3,600 meters above sea level in a climate of high rainfall and dry winds. Páramos are known as water factories for their capacity to generate clean water. They also act as a climate regulator with capacity to absorb carbon dioxide. Colombia is home to the largest surface area of páramo ecosystems in the world, holding 98% of páramo plant species. These ecosystems also are home to an immense persity of flora and fauna, including the spectacled bear and Andean condor, the world’s largest flying land bird. Rich in precious metals, the páramos are threatened by mining developments, both existing and planned. In Colombia, for example, miners are looking to undertake extractive activities in the Santurbán páramo, which would put in peril a vital source of fresh water for millions of Colombians. AIDA is leading a campaign (in Spanish) that calls for a proper demarcation of the Santurbán páramo’s territorial boundaries in an effort to stop mining development, an activity prohibited in officially declared páramo zones. Glaciers Glaciers are large bodies of dense ice, snow and rocks. They can stretch down or across mountainsides -- depending on their weight -- as they flow into the water system. They can melt, evaporate or break up into icebergs. In Latin America, 70% of the earth’s tropical glaciers are found high in the Andes mountain range of Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru (OLCA, 2013, in Spanish). Glaciers regulate water supplies by releasing water in the form of meltwater in the hot and dry seasons and by storing it as ice during cold and wet periods. In Ecuador, the city of Quito gets 50% of its water from glacier reservoirs and likewise Bolivia’s La Paz gets 30% from glacier catchment areas. Glacier melt, caused by the effects of climate change, is the greatest threat to the glaciers. Since 1970 the Andean glaciers have lost 20% of their volume, according to a report by Peru’s National Meteorology and Hydrology Service (SENAMHI, in Spanish). See the documentary La Era del Deshielo (The Age of the Thawing) by Señal Colombia. Source: YouTube Glacier melt is putting the water production of Andean countries at risk. In Peru, for example, the volume of surface ice that has been lost as a consequence of melting equates to seven billion cubic meters of water, a quantity that represents around 10 years worth of water supplies for the city of Lima. If all the world’s glaciers melted, sea levels could rise by some 66 meters, causing catastrophic impacts on coastal cities (OLCA, 2013, in Spanish). Como vemos, América Latina es una región totalmente rica en biopersidad que juega un papel importante en el mundo y en la continuidad de la especie humana. La belleza y riqueza del continente quedan expresadas en la letra de América, canción de Nino Bravo: “Cuando Dios hizo el Edén, pensó en América”. ¡Defendamos y preservemos nuestro Edén!

Read moreMexico’s government is held internationally accountable for authorizing tourism infrastructure in the Gulf of California

The Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) called on Mexican authorities to respond by January 8, 2014 to a complaint of breaching environmental legislation in the permits for four mega resorts. Mexico City, Mexico. The Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) requested an explanation from the Mexican government for authorizing tourism projects in the Gulf of California. The international organization, established under the North American Free Trade Agreement, made the determination after reviewing a citizen petition submitted by Mexican and U.S. organizations[i] denouncing the systematic violation of Mexican environmental law in permits for the construction of four mega resorts that put at risk fragile coral reefs, mangroves and wetlands. The Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA) and Earthjustice filed the petition[ii] with the CEC in April on behalf of 11 Mexican and international organizations. In the petition, the four resort projects are presented as an example of how Mexico’s Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) endorsed massive tourism infrastructure in the Gulf of California in violation of norms for environmental impact assessment, the protection of endangered species and the conservation of coastal ecosystems. The CEC Secretariat determined that the Mexican government has until January 8, 2014 to provide a response on why it issued the permits, specifically in relation to these aspects: use of the best available information, assessing the cumulative impacts and destruction of ecosystems, the lack of precautionary and preventive measures, and the omission of the power to suspend works. The CEC also requested information on the implementation of the resolutions and recommendations of the Ramsar Convention, an intergovernmental treaty for the protection of wetlands of international importance like those in the Gulf of California. “It is a breakthrough in national and international law because it recognizes these provisions as part of the implementation of the obligations in the international treaties ratified by Mexico,” said Sandra Moguel, an AIDA legal adviser. The Secretariat acknowledged, in particular, the resolutions adopted by the contracting parties to the Ramsar Convention, which establish standards for the environmental impact assessment and protection of wetlands. The Secretariat also acknowledged the recommendations of the Ramsar Missions that visited the Marismas Nacionales and Cabo Pulmo, concluding that large-scale tourism developments were not appropriate because of the vulnerability of these ecosystems[iii]. It asked Mexico to explain its failure to perform an environmental impact assessment in accordance with these provisions. “The CEC called for accountability from the Mexican government with respect to the abuse of discretion in considering technical reviews, as is the case with the Playa Espíritu project that lacked environmental viability according to the CONANP (National Commission on Protected Areas),” said Eduardo Nájera, director of COSTASALVAjE, one of the petitioning organizations. “It is urgent that the new administration of SEMARNAT doesn’t not make the same mistakes as their predecessors, and that it carry out a transparent and non-arbitrary environmental impact assessment, especially in the case of projects that could put in danger wetlands of priority international importance such as Marismas Nacionales, Cabo Pulmo and the Bahía de la Paz,” said Carlos Eduardo Simental, director of the Ecological Network for the Development of Esquinapa (REDES), another petitioner.Finally, Carolina Herrera, a Latin America specialist for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), said that she expects that once it receives Mexico’s response, “the CEC will elaborate a detailed investigation of what happened in order to press Mexico to not relax its own environmental protection measures in favor of unsustainable coastal development.” See the CEC determination. [i] Ecological Network for the Development of Esquinapa (REDES), Friends for the Conservation of Cabo Pulmo (ACCP), Mexican Center for Environmental Defense, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), COSTASALVAjE, SUMAR, Niparajá Natural History Society, Los Cabos Coastkeeper, Alliance for the Sustainability of the Northwestern Coast (ALCOSTA), Greenpeace Mexico and AIDA. [ii] For more information about the citizen submission mechanism, please see this link. [iii] These missions are a technical assistance facility of Ramsar whose primary purpose is to assist parties that have wetlands meriting priority attention due to changing ecological characteristics.

Read more