Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

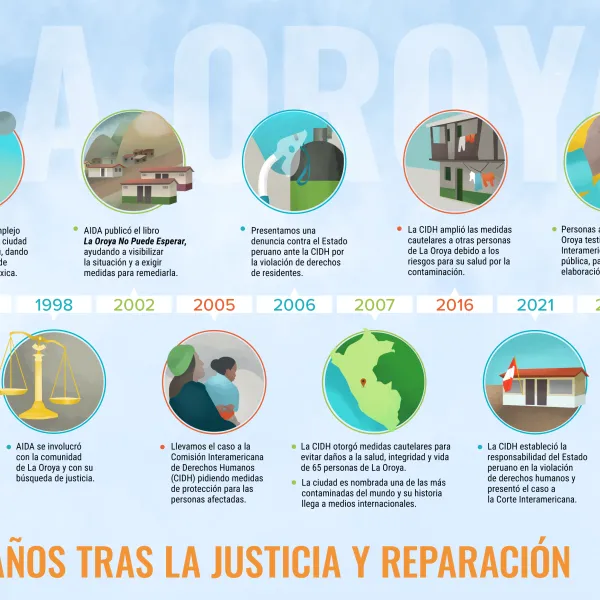

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Can COP19 move the Green Climate Fund closer to reality?

By Andrea Rodríguez, AIDA's legal advisor, and Marcus Pearson, AIDA's volunteer (article published in Respond/RTCC Magazine) The Green Climate Fund was created as an effective response to the impacts of climate change by channeling financial resources from developed to developing countries. Will this happen? The Conference of the Parties in November will provide an opportunity for developing countries to lobby for significant financial commitments from the developed world to ensure the long-term viability of the GCF. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was created in 2010 at the 16th Conference of the Parties (COP16) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Its mission is to channel public and private financial resources to developing countries to help them mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change through low-emission and climate-resilient programs. But nearly four years later, the GCF has yet to disburse any funds. The GCF board has held four meetings with only limited results. At the first meeting in Geneva in August 2012, the board selected two interim co-chairs: Mr. Zaheer Fakir of South Africa and Mr. Ewen McDonald of Australia. It also formed committees, designated the World Bank as Interim Trustee, and agreed to invite observer organizations to participate, albeit in a restricted capacity. A lack of consensus stalled decisions at the October 2012 meeting in South Korea, where the only notable motion was making Songdo, South Korea the GCF’s headquarters. More advances came at the February 2013 meeting in Berlin. The board adopted procedural rules to govern its actions, regulate board member selection and define the participation and role of civil society observers. This laid the groundwork for the GCF to carry out its mission. At the June 2013 meeting in South Korea, the board then discussed the GCF’s business model framework (BMF) and the policies, guidelines and organizational structures needed to commence operations. The board also chose the governance structure of the private sector facility (PSF) [i] and appointed Ms. Hela Cheikhrouhou of Tunisia as executive director of the GCF Secretariat. The fifth meeting in Paris could address the many outstanding issues still needed to bring the GCF into effective operation. To do so, the Board must overcome its perceived ineffectiveness. Civil society concerns Civil society organizations (CSOs) are concerned about the GCF’s decision-making process and future. Perhaps the greatest issue is the uncertainty of funding. The GCF board has started to identify project areas and define criteria to allocate resources, but developed countries have yet to pledge meaningful funds. Concrete commitments are essential to ensuring the availability of predictable resources needed to achieve long-term results to mitigate and protect against the impacts of climate change. CSOs also fear that a lack of transparency and accountability will hamstring the GCF. Transparency does not seem to be a priority for the board. For example, the board has decided against webcasting its meetings even though the UNFCCC commonly does so, helping to cut costs and carbon emissions associated with travel. If the GCF already broadcasts meetings to observers in an overflow room, why not webcast? CSOs fear the board does not want to make its meetings open to the public. Lack of public accountability remains a concern particularly because of the small opportunity given to civil society to participate in the decision- making process. The GCF will mobilize financial resources from both public and private sectors, and civil society oversight is needed to ensure that policies do not respond to the investment interests of the private sector but to the needs of the most vulnerable. Moreover, the board is not granting CSOs meaningful opportunities for participation. The GCF publishes documents before meetings without sufficient time for many CSOs to review and comment on proposals[ii]. Meanwhile, only two CSO representatives may actively participate at board meetings in person and even so may not be allowed to talk or approach board members[iii]. These practices call into question the GCF’s legitimacy. Globally, CSOs play a vital role in developing climate change policy by informing decision makers about local issues and needs, and by providing examples of best practices for resource allocation. Given that the GCF stresses accountability in its mandate, CSOs should have access to government representatives and information in open and transparent meetings. COP19: An opportunity for the GCF? The COP19 this November in Warsaw will show the world whether the GCF can become an effective engine for climate change funding in developing countries. At this conference, developing countries must seek firm financial commitments for climate adaptation and mitigation. Only guaranteed funding will enable the board to make effective decisions regarding resource distribution or provide developing nations with a clear picture of how much funding is available. The GCF Board must also seek -- and receive -- guidance because many COP attendees will benefit from GCF resources. Countries can use the COP to provide advice on GCF policies, share their priority needs for funding, and recommend criteria to guarantee access to resources. The COP will also give CSO representatives a chance to raise questions and highlight counterproductive practices. Conclusions The COP presents a prime opportunity for developed nations to commit to the GCF’s stated goals and pledge desperately needed financing. Parties and CSOs must use the COP – GCF’s monitoring body – as a tool to improve GCF accountability, inclusivity and transparency so that the GCF can truly work to benefit vulnerable populations in developing countries. The COP should be a benchmark for advancing the GCF rather than just another event for developed countries to congratulate themselves on timorous steps forward. [i] The PSF will enable the GCF to directly and indirectly finance private sector mitigation and adaptation activities at the national, regional and international level. [ii] For the June meeting in South Korea, documents were published less than two weeks before the meeting, rather than 21 days as outlined in the additional rules of procedure decision taken in Berlin. [iii] As was the case on the last day of the meeting in Songdo.

Read more

Climate change is real and will have a serious impact on human rights

By Héctor Herrera, AIDA legal advisor and coordinator of the Colombian Environmental Justice Network, @RJAColombia The impact of human-induced global climate change is already being felt, and going forward it will have a profound effect on the global population. Many people already believe the phenomenon exists, and they know about its likely impacts. But many others ignore the problem or deny it. In fact, the Climate Name Change initiative has compiled a list of policymakers who still deny climate change in the United States, a country with the greatest emissions of greenhouse gases in the Western Hemisphere. Watch the video Climate Name Change. Source: YouTube New and compelling evidence of climate change was published this year in the first part of the fifth report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which was commissioned by the governments of 195 countries and with input from over 800 international scientists. The most recent IPCC report found that: · The warming of the climate system is ‘unequivocal,’ · The odds that humans are the principal cause of climate change are at least 95%, · The Earth’s average surface temperature rose 0.85ºC between the years 1880 and 2012, · The Earth’s sea level rose 0.19 meters between 1901 and 2010, · Average global temperatures could rise between 1.5ºC and 4.5ºC by the year 2100, and · Sea levels could rise between 26 and 82 centimeters by 2100. There is scientific unanimity on climate change, and it will have a negative impact on human rights. It is worth noting that in 2008 the General Assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS) requested the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to investigate the link between climate change and human rights. Within this framework, AIDA published the report “A Human Crisis: Climate Change and Human Rights in Latin America,” which explains how the impact of global warming affects people’s ability to exercise their basic human rights in Latin America. It concludes that the IACHR should recognize the negative impacts of climate change on human rights and make recommendations to the OAS member states to fulfill their obligations to protect and guarantee human rights as global warming becomes more pronounced. The report mentions that the harmful effects of global warming include the loss of resources such as clean water as well as more extreme floods and storms, rising sea levels, more intense forest fires and droughts, and an increase in the spread of heat- and vector-borne diseases. These impacts, the document states, will have a profound effect on fundamental human rights such as the rights to a healthy environment, food, water, housing and a dignified life. AIDA says that in the face of such a scenario it is important to recognize that some communities are more vulnerable than others because they suffer from poverty or discrimination. The responsibility to take care of these communities is shared between different governments to varying degrees, which is to say that more responsibility falls on the states that have historically polluted the most. In sum, the report recommends that governments and other relevant bodies including intergovernmental organizations and international financial institutions adopt and promote measures to prevent human rights violations brought about by climate change. Althoughthese actions are executed on an institutional level, there are still many things we can do on a personal level. We can become informed of the problem, learn how to mitigate the effects of climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and apply these principles to our everyday lives. For example, you can ride a bike, reduce your electricity consumption or lessen your red meat intake. In short, the scientific community is certain that human-induced climate change is a reality. As AIDA notes in its report, the impact of global warming will seriously affect human rights in Latin America and around the globe. Now is the time to act! To learn more, visit the section on climate change on AIDA’s website.

Read more

The International Coral Reef Initiative and the role of AIDA

By Sandra Moguel, legal advisor, AIDA, @sandra_moguel Made up of government representatives, scientists and civil society members, the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) meets annually to discuss and make decisions on priority issues regarding the protection of international coral reefs. This year the meeting was held in Belize from October 14 to 17, hosted by ICRI Secretariat co-chairs Australia and Belize. The ICRI describes itself as an informal partnership between nations and organizations. It was created out of concern for the degradation of coral reefs, mainly as a consequence of human activities including land pollution, anchoring and more. Its objectives are to: 1) Encourage the adoption of best practices in the sustainable management of coral reefs and associated ecosystems; 2) Build capacity; and 3) Raise awareness at all levels on the plight of coral reefs around the world. Although ICRI decisions are not binding among members, they have been crucial in highlighting the important role of coral reefs and similar ecosystems in guaranteeing environmental sustainability, food security and social and cultural welfare. In its own documents, the United Nations has recognized the work and cooperation efforts of the ICRI in the international area. Much of AIDA’s work runs in parallel with the ICRI’s efforts. AIDA’s Marine Biopersity and Coastal Protection Program aims to ensure that Latin American coral reefs are legally protected and managed in a way that safeguards their biological integrity. This was reason enough for us to apply for ICRI membership so we could take part in this platform for dialogue. By participating in Belize, AIDA sought to identify opportunities to expand our work in high-priority countries and islands in the Americas. We also think it is important that the ICRI should take into account our expertise in international law and our partnerships with participating organizations. It is also key to apply a legal framework to the ICRI discussion, and there are some interesting ad hoc committees involved in the initiative that could explore this aspect. We are particularly interested in the economic value of coral reefs and similar ecosystems, a topic that also addresses the issue of compensation. Another interest is in the law enforcement committee that performs research on the assessment of the evidence and standardization of rules in different countries. Colombia, Costa Rica, Granada, Panama and the Marine Ecosystem Services Partnership (MESP) all attended the ICRI meeting in Belize as new members. Ricardo Gómez, Mexico’s representative to the ICRI, made a formal presentation of his paper entitled Regional Strategy for the Control of Invasive Lionfish in the Wider Caribbean[1]. In addition, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) presented its paper Status and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs: 1970-2012, edited by Jeremy Jackson, Mary Donovan and others. The paper looks at the changing patterns in coral reefs such as overfishing, coastal pollution, global warming and invasive species. The analysis concludes that rising tourism and overfishing are the most apparent causes of coral decline over the past 40 years. Coastal pollution is undoubtedly increasing, but no specific data are available to properly estimate its effects. Global warming also is a threat, but its effect was found to be of limited importance for now in the study. As a result of the study, the delegates approved a motion to ban fish traps, spearfishing and parrotfish fishing throughout the wider Caribbean and its adjacent ecosystems, and provide economic alternatives for affected fishermen. It also prompted a proposal to increase co-management agreements between government and civil society. At the meeting the delegates also discussed a simplification and standardization for monitoring the reefs and to make the results available in a database to facilitate adaptive management. It would be accompanied by a data exchange for local managers to benefit from others’ experiences. At the closing of the event, the delegates revised the ICRI Action Plan and held a ceremony to transfer the Secretariat responsibilities to Japan and possibly Thailand, which will be in charge of the administration of the ICRI in 2014. I really enjoyed working with my colleague and friend Haydée Rodríguez, another legal advisor at AIDA, who I talk with on a daily basis even though we live in different countries. I very much enjoyed discussing the scientific and management aspects of the coral reefs with experts in the protected marine environments of different countries. Although faced with similar problems, they resolve them in different ways because the same solutions cannot always be replicated in different contexts. In my point of view, the biggest challenge the ICRI faces is financing its platform. I also think it’s important to invite new members to encourage a greater representation from the government, scientific and civil society communities. [1] ReadEl Pez León y la necesidad de combatir especies invasoras(in Spanish, 20-noviembre-2012).

Read more