Project

Photo: Andrés Ángel / AIDASupporting Cajamarca’s fight to defend its territory from mining

Cajamarca is a town in the mountains of central Colombia, often referred to as "Colombia’s pantry” due to its great agricultural production. In addition to fertile lands, fed by rivers and 161 freshwater springs, the municipality features panoramic views of gorges and cloud forests. The main economic activities of its population—agriculture and tourism—depend on the health of these natural environments.

The fertile lands of Cajamarca are also rich in minerals, for which AngloGold Ashanti has descended on the region. The international mining conglomerate seeks to develop one of the world’s largest open-pit gold mines in the area. Open-pit mining is particularly damaging to the environment as extracting the metal involves razing green areas and generating huge amounts of potentially toxic waste

The project, appropriately named La Colosa, would be the second largest of its kind in Latin America and the first open-pit gold mine in Colombia. The toxic elements that an operation of that magnitude would leave behind could contaminate the soil, air, rivers and groundwater.

In addition, storms, earthquakes, or simple design errors could easily cause the dams storing the toxic mining waste to rupture. The collapse of similar tailings dams in Peru and Brazil in recent years has caused catastrophic social and environmental consequences.

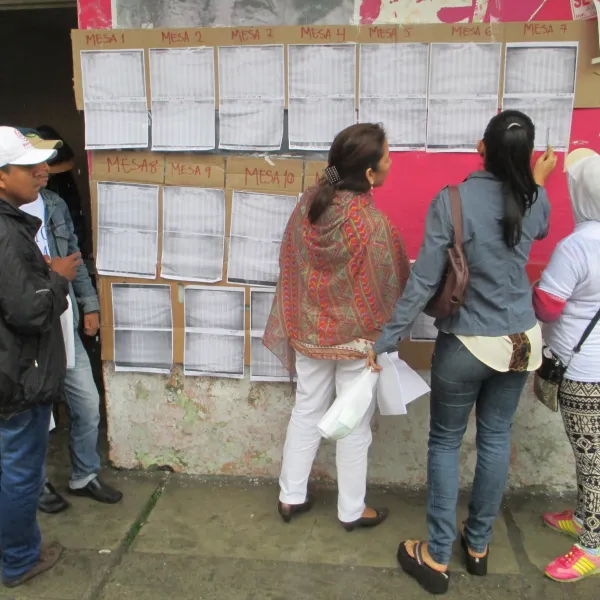

On March 26, 2017, in a popular referendum, 98 percent of the voters of Cajamarca said “No” to mining in their territory, effectively rejecting the La Colosa project. AIDA is proud to have contributed to that initiative. But even with this promising citizen-led victory, much work remains.

Related projects

More than 20,000 petition Colombia to stop aerial spraying of herbicides

Less than 24 hours before the National Narcotics Council decides whether to suspend the spraying, organizations deliver a citizens’ petition seeking a halt to social and environmental damages. Bogota, Colombia. A coalition of nongovernmental organizations delivered a petition with more than 20,000 signatures to the Ministry of Justice today, urging a stop to widespread aerial spraying of glyphosate and other harmful chemicals over large swaths of land in Colombia with the objective of eradicating coca and poppy crops. The petition highlights the need to protect the environment and human health from damages caused by the spraying, which is done over forests, homes, farms and water sources. Organizations sponsoring the petition, which was posted on the website Change.org, include the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), the Institute for Development and Peace Studies (INDEPAZ), the Observatory of Crops Declared Illicit, the Washington Office on Latin America, and Latin American Working Group. “In just a few days we received more than 20,000 signatures saying ‘no’ to the fumigation, not only with glyphosate, but with any herbicide used as an instrument in the war against drugs,” said Camilo González, Colombia’s former Minister of Health. The National Narcotics Council, chaired by the Ministry of Justice, will meet today to decide whether or not to suspend the spraying. “The Council should make its decision on the basis of law, considering scientific and technical evidence about the harmful impacts of spraying and the lack of desired results,” concluded Hector Herrera, attorney for AIDA and coordinator of the Environmental Justice Network of Colombia. Alongside sponsoring organizations, the signers of the petition emphasize that the spraying should come to an end because it: Causes serious health impacts: The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer determined that glyphosate may cause cancer in humans. Independent studies have also documented other serious health effects from the spraying, such as skin diseases and problems during pregnancy. Has not achieved its objective: Over more than 15 years, the spraying has failed to reduce the cultivation of coca and poppy crops for illicit use. Causes serious environmental impacts: Spraying has been done indiscriminately over homes, farms and water sources. As a consequence, it has damaged biodiverse ecosystems and the species that live in them (fish, amphibians, rodents, insects, and endemic plants), polluted water, destroyed forests, and damaged food crops, a source of subsistence for many communities. Displaces people: Having no alternatives to coca and poppy cultivation, entire families have left their land because of the spraying. Ignores national and international socio-environmental standards: National tribunals such as the Constitutional Court have requested the suspension of spraying based on the precautionary principle. Colombia compensated Ecuador for the damages the spraying has caused along the border, and promised to suspend the practice in that region. National and international experts explained these and other reasons to halt the aerial spraying program in a seminar today at the Center for Memory, Peace and Reconciliation in Bogota. “For 40 years, the spraying of pesticides has been the subject of academic, scientific and legal analysis, which, though recommending the end of their application, have not always been public. These analyses have been dominated by politics of security and public order, but have left out health, environmental and legal recommendations. This approach has denied the existence of the socio-economic problems that persist in communities where crops are grown; it has denied the importance of recognizing the human rights of rural communities; and it has not recognized the new approach recommended by the United Nations Development Program to contain the expansion of illicit crops,” explained Pedro Arenas, coordinator of the Observatory of Crops Declared Illicit, who moderated the discussion group. The Ministry of Health, the provincial and district secretaries of Health, the Ombudsman, and the Attorney General’s Office, among other authorities, agree with the thousands of people who signed the petition and the organizations that have promoted it. The petition is still open for signatures! Sign Here: chn.ge/1zPK74G!

Read moreIFC boosts investment in contested Canadian mining project in Colombia despite ongoing investigation

Washington, DC – On April 24, more than 50,000 Colombians took to the streets in Bucaramanga in a march to defend their primary water source from the development of Eco Oro Minerals’ Angostura gold project and other proposed mining activities. Despite broad public opposition and an ongoing investigation into an earlier investment decision, the private lending arm of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), bought more shares in Eco Oro Minerals in February. The IFC’s original decision in 2009 to invest in Eco Oro is the subject of an ongoing investigation by the World Bank’s Compliance Advisor Ombudsman about whether its social and environmental sustainability policies were violated. In February, without waiting for a decision on the ongoing investigation, the IFC purchased an additional 390,000 shares in Eco Oro Minerals for a total investment of US$18.4 million. Members of the Committee for the Defense of Water and the Santurbán Páramo brought the original complaint to the CAO in June 2012 and have decried the fact that mining is illegal within the páramo. "This mining project and the others that it stimulates in the area will put the drinking water of millions of us at risk. We have clearly stated that we want the IFC to divest, not reinvest," remarked Carlos Lozano Acosta, attorney at the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). The Santurbán Páramo is a high altitude wetland ecosystem that provides water for approximately 2 million people in the region. "This new investment is irresponsible. The IFC needs to learn from the past; investments in mining have led to violent conflict and human rights violations throughout Latin America, stated Carla Garcia Zendejas, Program Director at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). “Given that there is an open investigation, at a minimum the IFC should wait for their own compliance office to determine if their original investment in the mine violated their own policies before making any further decisions" Garcia Zendejas said. Violence has already taken place in the area of Eco Oro operations. The complaint presented to the CAO alleges that the IFC glossed over potential security issues related to the Angostura project. It includes documented evidence of violence associated with guerrilla and paramilitary activity following a major military operation and the establishment of military installations in the area around 2003. “The IFC is investing in conflict and lending legitimacy to an activity that downstream communities and organizations have clearly opposed out of concern for their future well-being. The IFC should start listening to the Colombian people and withdraw,” commented Jen Moore, Latin America Program Coordinator for MiningWatch Canada.

Read moreOrganizations ask for immediate suspension of aerial fumigations of glyphosate and other chemicals in Colombia

A citizen petition was released by the website Change.org addressed to President Juan Manuel Santos and the National Narcotics Council. It requested that such fumigations are suspended because they damage the environment, human health and may cause cancer. Bogota, Colombia. The Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), with the help of the Institute for Development and Peace Studies (INDEPAZ) and the Observatory of Crops Declared Illicit, launched a citizen petition today open to signatures through the website Change.org to request that president Juan Manuel Santos and the National Narcotics Council suspend aerial spraying of illicit crops using glyphosate and other harmful chemicals. "Independent scientific studies show that the fumigations are inefficient and have not reduced coca and poppy crops. To the contrary, they have contributed to the destruction of forests and affected populations, including ethnic groups. Recently, the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization (WHO) determined that the glyphosate usedin in spraying may cause cancer in humans," says Astrid Puentes Riaño, AIDA Co-Executive Director who signed the petition. The National Narcotics Council will meet on May 14 to address the issue and decide whether to suspend the spraying. In the case of Colombia, this practice is carried out on a mass scale, through aerial spraying and uses a concentration of glyphosate higher than that used commercially. In addition, the spraying occurs indiscriminately over houses, farms and water sources. On April 24 and based on the determination of the WHO, the Ministry of Health recommended the National Narcotics Council immediately suspend aerial spraying of glyphosate, which was introduced to the country more than 15 years ago with funding from the United States Government. In the past, high courts in the country such as the Constitutional Court have also solicited the suspension of the spraying, but these provisions have not been met. This issue reached the International Court of Justice when Ecuador sued Colombia for impacts of the fumigations in the border area. The Colombian government compensated the neighboring country and pledged to stop spraying along the border. Apart from damage to health, the fumigations impact ecosystems rich in biodiversity and the species that inhabit them, pollute water and destroy food crops that are a source of subsistence for indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities and small farmers.

Read more