Project

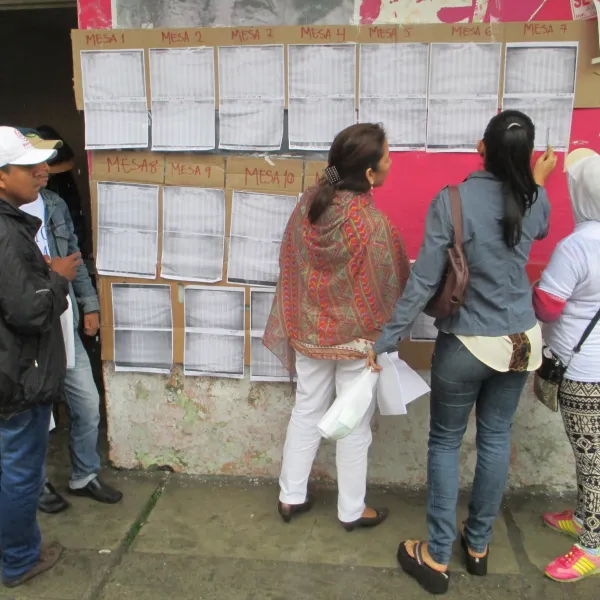

Photo: Andrés Ángel / AIDASupporting Cajamarca’s fight to defend its territory from mining

Cajamarca is a town in the mountains of central Colombia, often referred to as "Colombia’s pantry” due to its great agricultural production. In addition to fertile lands, fed by rivers and 161 freshwater springs, the municipality features panoramic views of gorges and cloud forests. The main economic activities of its population—agriculture and tourism—depend on the health of these natural environments.

The fertile lands of Cajamarca are also rich in minerals, for which AngloGold Ashanti has descended on the region. The international mining conglomerate seeks to develop one of the world’s largest open-pit gold mines in the area. Open-pit mining is particularly damaging to the environment as extracting the metal involves razing green areas and generating huge amounts of potentially toxic waste

The project, appropriately named La Colosa, would be the second largest of its kind in Latin America and the first open-pit gold mine in Colombia. The toxic elements that an operation of that magnitude would leave behind could contaminate the soil, air, rivers and groundwater.

In addition, storms, earthquakes, or simple design errors could easily cause the dams storing the toxic mining waste to rupture. The collapse of similar tailings dams in Peru and Brazil in recent years has caused catastrophic social and environmental consequences.

On March 26, 2017, in a popular referendum, 98 percent of the voters of Cajamarca said “No” to mining in their territory, effectively rejecting the La Colosa project. AIDA is proud to have contributed to that initiative. But even with this promising citizen-led victory, much work remains.

Related projects

Organizations come out in defense of the Veracruz Reef System

Technical and legal arguments are submitted in support of a lawsuit against modifying the boundaries of the Veracruz Reef System National Park in eastern Mexico, a site protected by international obligations to preserve the natural barrier against storms and hurricanes. Veracruz, Mexico. Six civil society organizations have submitted to a Mexican court an amicus curiae brief containing legal and technical arguments that strengthen arguments in a lawsuit against a government decree to modify and reduce the boundaries of the Veracruz Reef System National Park. The proposed modification puts conservation of this internationally important wetland at stake. The organizations submitted the friend of the court brief to the Third Tribunal of the District of Veracruz on April 25. They are the Interamerican Association of Environmental Defense (AIDA), the Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA), the Strategic Human Rights Litigation Center (Litiga OLE), Pathways and Encounters for Sustainable Development (SENDAS), Pobladores A.C. and the Veracruz Assembly of Environmental Initiatives and Defense (LAVIDA). The Veracruz Reef System in eastern Mexico was declared a natural protected area in 1992 to safeguard its diversity of species and a rational use of its resources, and to encourage research into the ecosystem and its balance. In 2004, the Veracruz Reef System was included as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty to protect wetlands. The amicus curiae (friend of the court) brief highlights the importance of the reef system for Mexico and the region. “Coral reefs are natural barriers against large waves and storms like Hurricane Karl, which hit Veracruz in 1992,” said Sandra Moguel, a legal advisor to AIDA. “Reefs also provide abundant fishing and valuable information for medical research. They’re great spots for recreation and they help to sustain marine life.” The legal brief also argues that the decree, from Mexico’s National Commission on Protected Areas (CONANP), threatens regional biodiversity, violates the human right to a healthy environment, and breaches Mexico’s international obligations to protect this ecosystem. “The local population is more exposed to suffer the impacts of hurricanes and other climate phenomena, because the decree removes the Punta Gorda and Bahía de Vergara reefs from the national park,” said Xavier Martínez Esponda, regional director of CEMDA for the Gulf of Mexico. The organizations’ brief explains how CONANP’s decree infringes specific national laws and international treaties. For example, the Organization of American States’ Convention on Nature Protection and Wild Life Preservation in the Western Hemisphere states that natural park limits can only be modified by legislative authorities. CONANP is not such an authority. The decree also violates the Ramsar Convention, given that the modification of the national park’s defined boundaries did not follow the procedures established by that intergovernmental treaty for the protection of wetlands of international importance. The brief concludes by making it clear that CONANP’s decree is a regressive measure that erases the benefits of environmental protection attained with the creation of the protected area in 1992. “Setbacks like this can cause irreparable damage,” said Moguel.

Read more

Frustration to hope: Finding the drive to continue from those you help

By María José Veramendi Villa, senior attorney, AIDA, @MaJoVeramendi I can get frustrated in my work as an environmental and human rights lawyer. It is frustrating to explain that the work we do on cases of human rights violations may not produce immediate results. It is frustrating to know that our work is a struggle that can take years to find justice for victims and induce change in state policies and our societies. It is frustrating to watch programs designed to protect human rights come under the influence of political interests. The dearth of resources for pursuing these cases is also frustrating. So too are the long waits for justice – or injustice. So what do we do when we get discouraged? My answer is to return to the origins, the basics and the very reason for our struggle and commitment: the victims. I relearned this lesson in March. On a trip to Washington D.C., I met two Brazilian fighters for the cause of their communities: Alaíde Silva and Josías Manhuary Munduruku. Alaíde had traveled for days from Buriticupu, a municipality in the northeastern state of Maranhão, and Josías from Jacareacanga, a municipality in the northern state of Pará, to participate in a hearing (in Spanish and Portuguese) before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. They came to present information on how Brazilian judges are continuing to use a law from the country’s 1964-85 dictatorship to violate their right to access to justice. The law is called Security Suspension. It allows the federal government to request the suspension of judicial rulings. The government has used Security Suspension to invalidate rulings that favor the rights of indigenous peoples and other communities against the development of mega-projects like the Belo Monte hydropower dam in the Amazon. The government can do this on the basis that any adverse rulings to “development” projects are threats to national security or to social and economic order. At the hearing, Josías described an imminent threat to the Munduruku indigenous community of 11,000 people in 118 villages. The Brazilian government plans to build a hydropower complex (in Spanish) on the Tapajós River and its tributaries—and has not followed a law requiring it to consult the Munduruku and to obtain their prior, free and informed consent. He said flooding from the project threatens to devastate his people’s land and the survival of their community and culture. He explained how a judge revoked a favorable court decision for his people, allowing the project to continue in open violation of their rights. “We want respect for our land, our river, our sacred sites, our cemetery. And want to be consulted!” Josías said. Alaíde spoke about a similar plight. He explained how Vale, a Brazilian mining company, is enlarging the Carajás Railroad to the detriment of 1.7 million people in 27 municipalities in Maranhão and Pará and in at least 100 indigenous, Afro-descendants, peasant and urban communities on the banks of the railway. The railroad stretches 900 kilometers from the Carajás mines in Pará to the Ponta da Madeira Maritime Terminal in Maranhão. It transports iron, manganese, copper and coal. With the expansion, Vale will duplicate 115 kilometers of the line to increase transport capacity and the flow of minerals. Alaíde said the impacts are vast. These range from the noise pollution caused by the grinding of the train wheels on the tracks and from the train horn, to the running over of people and animals, to the displacement of communities, villages and families without fair compensation. Alaíde provided details on how Vale terrorizes the population, co-opts leaders, intimidates people and spies on social movements, all in the name of meeting its own interests. As with Tapajós, Security Suspension was used to revoke a court ruling that had favored the communities. That decision had ordered Vale to suspend construction and conduct an environmental impact assessment with a detailed analysis of all the existing indigenous and Afro-descendant communities along the railroad. But with Security Suspension, this ruling was overturned with the argument that suspending the project would affect the economic interests of the state. These are just two examples of the impact of Security Suspension. There are many more instances in which the rights of communities and people have been affected by major “development” projects justified by “economic interest, public order and safety.” We hope that cases like these will expose the impact that Security Suspension has on the human rights of hundreds of people and communities, and we hope that this will drive international organizations to call on Brazil to change this legal instrument. Thanks to everyone who worked so hard to make the hearing possible. Thanks to our colleagues in Brazil without whose work and commitment Alaíde and Josías would never have been able to make the long journey. And thanks to these two Brazilian human rights fighters for a lesson that drives away the fog of frustration and allows the sun to shine again. I want to dedicate this post to my dear former colleague Joelson Cavalcante, who recently left this world to become a being of light. With him I visited the Xingu River in the Brazilian Amazon for the first time, and I will never forget his happiness and his big smile when, after a year outside his country, he could once again swim in those waters. In his memory, the fight continues.

Read moreCOP20: A chance to fight climate change

The world is poised for more poverty, hunger and disease as flooding, heat waves, storms and droughts increase. This is how the newest report of the the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change describes humanity´s near future. That’s why AIDA is helping Latin American policymakers to influence decisions about climate change responses at the highest levels of international law. We’re building their capacity for influence by developing recommendations and disseminating information. This year Latin America has the best opportunity yet to put its needs on the international climate change agenda. In December, Lima will host the main session of climate negotiations, the 20th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP20). The event’s mission is to advance the draft of a new binding climate agreement to be signed at the Paris climate conference in 2015. To make the most of this opportunity, AIDA is supporting policymakers – government officials, negotiators and members of international financial institutions – and civil society organizations. Our objectives are to help them participate more effectively in the climate negotiations, to educate them about options for improvements in international law, and to encourage them to create solutions and press their governments to take immediate action. In March, we took part in Climate Change: Progress and Prospects, an international forum held in the Peruvian Congress. Peru is considering creating a climate change bill, and at the event we shared our experiences in international climate finance. We highlighted the need for Latin American institutions to improve their ability to access funds for climate change adaptation and mitigation projects. We’re also advocating a commitment to long-term financing as a chief component of the new climate agreement that will be discussed at COP20. If countries know that economic resources will become and remain available, they can plan viable actions to help communities most vulnerable to climate change. In February, AIDA and our partner organizations held a webinar on the Green Climate Fund (GCF), a financial mechanism of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The GCF was founded to mobilize large amounts of public and private money to support climate change responses in developing countries. AIDA is closely monitoring the GCF to make sure that its contribution is effective. Your renewed support will help us to do even more to generate effective international actions that reduce the severity of climate change. As we actively prepare for COP20 and continue our efforts to promote sustainable energy alternatives at the regional level, we will keep you informed of our progress. Thank you!

Read more