Project

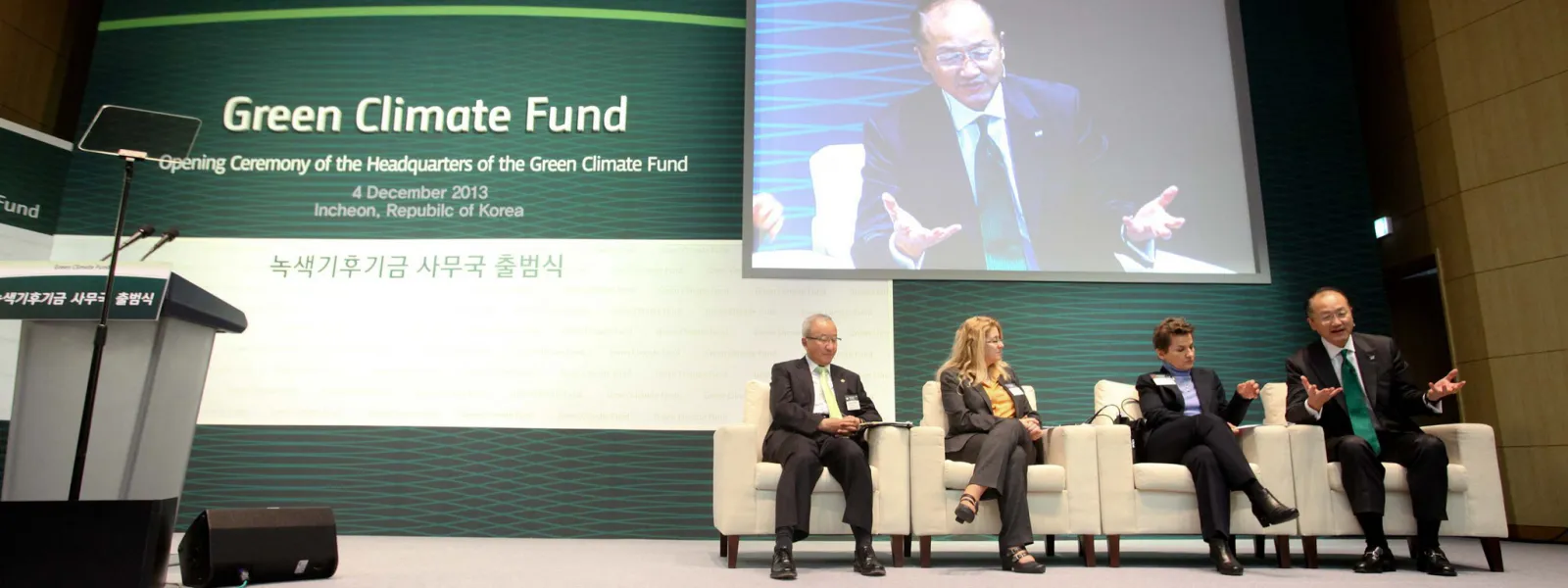

Photo: GCFAdvocating before the Green Climate Fund

The Green Climate Fund is the world's leading multilateral climate finance institution. As such, it has a key role in channelling economic resources from developed to developing nations for projects focused on mitigation and adaptation in the face of the climate crisis.

Created in 2010, within the framework of the United Nations, the fund supports a broad range of projects ranging from renewable energy and low-emissions transportation projects to the relocation of communities affected by rising seas and support to small farmers affected by drought. The assistance it provides is vital so that individuals and communities in Latin America, and other vulnerable regions, can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and address the increasingly devastating impacts of global warming.

Climate finance provided by the Green Climate Fund is critical to ensure the transformation of current economic and energy systems towards the resilient, low-emission systems that the planet urgently needs. To enable a just transition, it’s critical to follow-up on and monitor its operations, ensuring that the Fund effectively fulfills its role and benefits the people and communities most vulnerable to climate change.

Reports

Read our recent report "Leading participatory monitoring processes through a gender justice lens for Green Climate Fund financed projects" here.

Partners:

Related projects

COP 20: And what about the effective use of climate finance?

The amount of money required to confront the effects of extreme climate changes is much larger than currently sought in global negotiations. Clearly more resources are needed, but it is also important to track the effective use of climate finance now being mobipzed. "We must recognize the funding gap for adaptation programming," said Annaka Peterson Carvalho of Oxfam America. She was a panel member Wednesday at a COP20 event entitled, A fair and accountable cpmate finance regime: Confronting the contentious issues. In her opinion, we must determine, on the basis of science, the real costs that countries must rightfully bear, and we need a responsible finance system to determine how much money each country needs and where it will come from. Sandra Guzmán, General Coordinator of the Cpmate Finance Group of Latin America and the Caribbean (GFLAC), agreed that while it is necessary to have more resources for the fight, it’s also necessary to use them effectively. "It’s not just about asking for more money," she said. "We must change priorities at a national level to distribute funding by reassigning it to activities that allow for reduced emissions." Guzmán explained that the Climate Finance Group has developed a methodology to know how much money each country receives, and how much they spend in deapng with climate change. Their analysis encompasses many activities, including some that are not traditionally labeled as relating to cpmate change. She identified five challenges in the task of tracking the use of cpmate finance: Transparency and access to information; Definition of the criteria of climate finance; Institutional structure and communication between different institutions; Public participation in the evaluation of projects; and Better methodology for monitoring, reporting, and verification to analyze the effective use of the money. The experience of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (iCSC) in the Philippines demonstrates that accountability on climate finance is “everybody’s business,” according its Executive Director, Red Constantino. The Institute tracks not only committed funding for adaptation, but also how it is channeled locally. The work that Constantino has done has enabled him to identify difficulties in apgning funding with the real needs and priorities of vulnerable communities; provide limited opportunities to involve communities in decision-making about adaptation; and understand that while money flows, it is not necessarily used efficiently or completely. Andrea Rodríguez, senior lawyer at AIDA, also referred to the importance of ensuring that climate change programs and projects meet the requirements of individual countries and are directed by them. To be effective, she said, the new climate regime must find ways for countries to monitor climate finance, learn from the experiences of other institutions, and reallocate their resources to be effective. "Climate finance responds to a specific need, it is not general assistance for development," Rodríguez added. "Public participation is central to the process, and if we know how much money we need and how to use it, we will know how much to ask for in global negotiations. In this sense, Constantino highlighted coordination between local and national levels, between governments and civil society. For more information from COP20 and to post comments, visit our interactive blog at aida-cop.org

Read more

COP20: Protecting human rights in all climate actions

By Víctor Quintanilla, AIDA Communications Coordinator, @vico_qs All countries have an obligation to fight climate change. But they must also protect the human rights of their people. The fact that officially recognized clean development projects aimed at combating climate change often cause grave human rights violations was discussed Tuesday at a side event at the COP in Lima. Co-hosted by AIDA, the p for International Environmental Law (CIEL), and Carbon Market Watch, the side event asked the question, "How can the lessons learned from the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) influence the design of climate finance mechanisms?" Máximo Ba Tiul stood before the room and spoke of the grave impacts of the Santa Rita hydroelectric project, which was registered under the CDMof the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. A representative of the Tezulutlán Indigenous Council of Guatemala, Ba Tiul explained that the so-called clean development project has caused human rights violations, including the death of children, in at least 20 surrounding communities. Implementation of hydroelectric projects, Ba Tiul explained, often imply human rights violations: Shirking international standards, Santa Rita was approved without consulting or obtaining the free, prior, and informed consent of affected populations. Hugh Sealy, President of the Board of the CDM, replied that he was "disturbed" to hear that a CDM-registered project had allegedly violated human rights. While hydroelectric projects such as Santa Rita are promoted as clean energy solutions to climate change, scientific evidence has shown that large dams, particularly those in the tropics, release large quantities of methane, a greenhouse gas 20 to 40 times more potent than carbon dioxide. "All countries must respect human rights," Niranjali Amerasinghe, director of CIEL’s Climate & Energy Program, said during the event. He explained that the connection between climate change and human rights, or, more precisely, the impact of one on the other, has been recognized in previous climate agreements, such as those drafted at COP16 in Cancun, Mexico. Amerasinghe advocated for consistency within the Convention in terms of applying social and environmental safeguards. Andrea Rodriguez, an AIDA senior attorney, spoke of the importance of implementing such safeguards, particularly with respect to the Green Climate Fund. The Fund must adopt the strictest standards in the design of their social and environmental safeguards, she said. Only in this way can they ensure that projects financed won’t cause harm to the environment or violate human rights. Rodriguez said that the best international standards must be applied to projects at every phase of development, along with ongoing evaluation to learn from mistakes and to guide the choice of tools that have proved most effective. During its first three years of operation, the Green Climate Fund will use the standards of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which Rodriguez considers "insufficient for preventing harm." Ba Tiul noted that the challenge is for all United Nations entities to honor differences and respect human rights. Amerasinghe added that projects registered with mechanisms like the CDM should be monitored throughout implementation, not just during the initial consultation and approval phases. And, faced with allegations of human rights abuses, he said, authorities must not hesitate to undertake an investigation. At the conclusion of the event, Sealy thanked the participants for the information provided and promised to do everything possible to strengthen the Clean Development Mechanism consultation process. For more information from COP20 and to post comments, visit our interactive blog at aida-cop.org

Read moreCOP20: It’s All On Our Shoulders Now

ECO/Climate Action Network We are very happy to be in Lima, and ECO is ready to get right to it. COP20 needs to deliver on enough confidence building measures to ensure climate action and a successful outcome from next year’s COP in Paris. The wheels have already started turning: The Peruvian COP presidency has shown commitment and substantial effort to guide the negotiations onto the right track. The US-China climate announcement, on the heels of similar action by the EU, has injected positive impetus into the political aspect of the negotiations – and is pressuring significant laggards and defaulters, who can no longer claim inaction by the G2 to wiggle out of doing their part. The IPCC is shining clear light on the latest science, pointing urgently to deeper climate action as well as the fast-rising costs of delay. The GCF is seeing some light at the dim end of the climate finance tunnel with pledges at $9.7 billion for initial capitalization – though that’s welcome, it must not distract from the pressing need to scale up finance within the new agreement. Are these announcements and developments enough to create the right confidence building measures across countries, cement the foundation for greater political will and achieve success in Paris? ECO surely hopes so – but let’s be clear, this opening round of mitigation announcements must not be a resting place but rather a starting point that Parties will broaden and expand. The agreement in Paris is going to rest on three key decisions here in Lima: the elements of the 2015 agreement, the iNDC upfront information requirements, and ways to ramp up pre-2020 ambition. These outcomes are going to define the contours of the new global agreement. So let’s look a bit closer. The elements text must include a long-term goal of phasing out all fossil fuel emissions and phasing in 100% renewable energy as early as possible, but not later than 2050. We also expect to see goals for public finance along with a robust and honest MRV regime for them; a global adaptation goal that enables adaptation to be mainstreamed; and a strengthened two-year work plan to immediately operationalize the Warsaw loss and damage mechanism and to ensure that loss and damage has its appropriate place within the 2015 agreement. Not so easy, right? Well, don’t worry, as always, ECO is here to help. And with that in mind, we also look forward to seeing the inclusion of an enhanced role for civil society in the text. To be clear, we have high hopes for the iNDC text. The iNDCs should include mitigation with regular 5-year cycles of contributions, starting with countries putting forward their contributions for the 2020-2025 cycle, provision and mobilization of finance as part of countries’ fair share of the global effort, and voluntary adaptation contributions. Not only that, all current and future contributions must undergo a sound, robust equity and adequacy assessment phase to help drive up ambition and ensure that low ambition is not locked in by any country. The first round of iNDCs will set the tone for the future. We’ve really got to get it right on this one – it is no exaggeration to say the future of human civilization is weighing on all our shoulders. And every step counts. The effectiveness of the post-2020 agreement to be reached in Paris next year depends on the progress we make between now and 2020. On pre-2020 finance it’s simple: developed countries have to present a credible roadmap on how they are going to meet their $100 billion promise, deliver additional pledges to the GCF (this means you, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Iceland and Ireland) and also not let the Adaptation Fund dry up. We need finance and a full set of means of implementation and support to unlock untapped potential in countries and sectors that can deliver greater ambition for reducing emissions, as well as assisting vulnerable communities that are already facing impacts from climate change. On mitigation, what has the latest IPCC report taught us? All countries need to increase their pre-2020 mitigation commitments, and deliver on them through real mitigation actions. As session after session has shown, climate impacts do not stick to UNFCCC timelines; the atmosphere sees what we do, not what we think. The pressure is on but ECO is confident we can respond. We’ve got a lot of work to do, and there is no time to lose. Archivado en: English

Read more