When nature is your best client

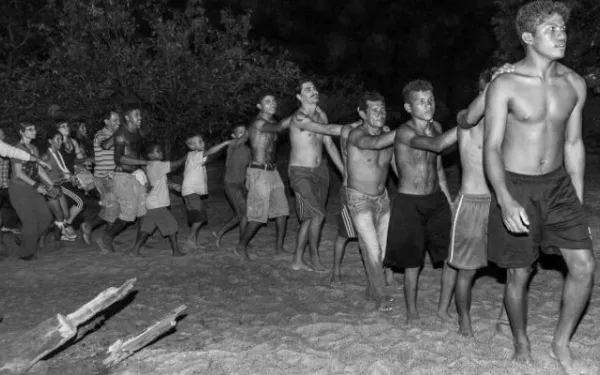

AIDA’s attorneys both hail from and live in Latin America, fostering a profound respect for the region’s natural environment and those who depend so intimately on it. They’re turning their knowledge into action, and working to protect communities and ecosystems vital to their national heritage. Uniting the environmental community in Bolivia Claudia believes in environmental justice. “If people are not guaranteed quality of life and an adequate natural environment, their basic human rights are being violated,” she said. This belief led her first to study law and then to work on behalf of civil society to promote the production of healthy, pesticide-free food. Small-scale agriculture, with less environmental impact and more community benefits, is what Claudia remembers best when she thinks of her childhood in Cochabamba, Bolivia. There were gardens behind every house. From a very young age, she grew berries and always had apples, figs, guava, and other fresh fruit on hand. But with urbanization, the valley where she grew up became a city, and buildings replaced the lush green landscape. “It was a complete shock to see these changes made in the name of progress.” Claudia knows that her contribution to a better world will come from environmental law, and that she will have a greater impact by reaching more people. That’s why she joined AIDA’s Freshwater Program, where she offers free legal support to governments, communities, and local organizations. One of Claudia’s greatest achievements has been to successfully unite isolated efforts across Bolivia to confront common environmental problems. This year Claudia oversaw the formation of the Environmental Justice Network of Bolivia, a space for organizations and individuals to develop joint strategies for environmental protection. As their first big event, the Network organized a two-day forum on how to achieve justice for damages caused by mining operations. “I’ve seen the ways that Bolivia’s indigenous peoples understand the world, and how they relate with Mother Earth. In cities, nature is seen as an object; for the indigenous, it’s the common house we must care for because it provides us with everything we have. I’ve made this vision my own.” Protecting coral reefs in Mexico Camilo’s first interaction with the ocean took place in Boca del Cielo, a remote beach on the coast of Chiapas, Mexico where a stream meets the sea. There, he played in the waves and ate seafood, saw his first sea turtle, and watched the monkeys and birds play in the tall mangroves. During his childhood in San Cristobal de la Casas, his father taught him to swim against the current in the Cascadas de Agua Azul, an important natural reserve. “My father loves nature and has always transmitted that feeling to my brothers and me,” said Camilo, who now lives with his son Emiliano en La Paz, Baja California Sur. Living in a coastal city has given him a newfound appreciation for the ocean and its vital connection to our land. Camilo applies this understanding to his work as an attorney with AIDA’s Marine and Coastal Protection Program. He is working, for example, to save the Veracruz Reef System, the largest coral ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico, which serves as a natural barrier against storms and hurricanes and is a source of livelihood for fishing communities. The site is seriously threatened by the expansion of the Port of Veracruz. Camilo is working so that the Mexican government respects the international treaties it has signed, which obligate the preservation of the site and the biodiversity found within. Camilo remembers, when he studied law in Chiapas, exploring caves in his free time, to which local farmers guided him. “Being in touch with nature often leads you to small communities who care for and revere their connection with the natural world, values you quickly come to understand and share.” Seeking the rain in Brazil If anyone knows the value of the rain, it’s the people of Paraíba State in northeast Brazil, who have for years been hit by an extreme drought. There, according to official information, the number of cities without water nearly doubled between 2016 and 2017. “The drought has shaped our customs, our eating habits, and our culture,” says Marcella, who was born in the State’s capital city of João Pessoa. Now living in Recife, she is a fellow with AIDA’s Human Rights and the Environment Program. Through her role as an environmental and human rights attorney, Marcella seeks to soften the effects of the drought in Paraíba. The way she sees it, she’s helping to do so through her work on the case of the Belo Monte Dam. “Large dams are dirty energy, and they’re damaging the Amazon rainforest, a key ecosystem that regulates climate and helps ensure it rains not just in Brazil but around the world. By working on this case, I’m fighting for the existence of rain in my State,” she explained. Last June, Marcella paid her first visit to Altamira, the city closest to Belo Monte. She spoke with people whose way of life had been destroyed by the dam. “I met someone who used to fish, grow his own food, and sell what was left in the city; because of the dam, his island was flooded and he lost everything.” For Marcella, there is no better way to understand the severity of the impacts of these inadequately implemented projects than to listen to those affected by them. “It gives me a notion of reality. Helping to get justice for these people is an obligation for me. It’s the best I can do, using the tool I know best: the law.”

Read more