Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

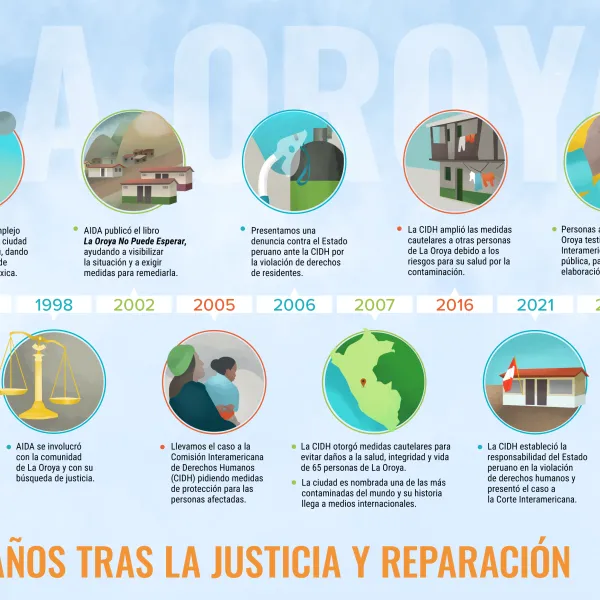

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Communities in Nicaragua win Green Climate Fund withdrawal from project that violated their rights

In an unprecedented decision resolving a complaint filed in 2021, the Green Climate Fund terminated a forestry project because the developers failed to comply with the Fund's policies and procedures on socio-environmental safeguards. This non-compliance violated the human rights of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. The Green Climate Fund, the world's leading multilateral climate finance institution, decided to terminate funding for a forest conservation project in Nicaragua because the developers failed to comply with the institution's policies and procedures on socio-environmental safeguards. The non-compliance violated the rights of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, as the project threatened to exacerbate the situation of violence from which they were already suffering. The Fund had not made any disbursements for the project and project implementation had not yet begun.The decision, the first of its kind in the Fund's history, is in response to a complaint filed in June 2021 by representatives of the affected communities, with the support of local and international organizations, with the Fund's Independent Redress Mechanism. The Independent Redress Mechanism hears complaints from people who are or may be affected by projects or programs financed by the Fund."This decision is a recognition of the tireless efforts of the communities behind the case, who were able to demonstrate the difficult situation they face, as well as a reminder of the importance of involving local communities in all stages of a project, from its conception," said Florencia Ortúzar, Senior Attorney at AIDA, one of the organizations that accompanied and provided legal support to the complaint process.In the complaint, the communities argued that implementing the project— called Bio-CLIMA: Integrated Climate Action to Reduce Deforestation and Strengthen Resilience in the BOSAWAS and Río San Juan Biospheres— would have serious impacts because:There was no adequate disclosure of information, no indigenous consultation, and no free, prior, and informed consent.The project would cause environmental degradation and increase violence against indigenous communities due to land colonization.The conditions imposed by the Fund's Board of Directors for project approval (including independent monitoring of project implementation and ensuring the legitimate participation of indigenous peoples) were not met.There was a lack of confidence in the Central American Bank for Economic Integration, the entity accredited to channel the funds, as to its compliance with the Fund's policies.There was a lack of confidence in the ability of the Government of Nicaragua, as the implementing agency, to fulfill its obligations in the execution of the project. The goal of the project, for which the Fund committed $64 million USD in 2020, was to restore degraded forest landscapes in Nicaragua's most biodiverse region (home to 80 percent of the country's forests and most of its indigenous peoples) and to channel investments toward sustainable land and forest management.However, the project was designed without adequate consultation, with a complete lack of transparency on the part of the sponsoring bank and ignoring the difficult context of violence and lack of human rights protection still suffered by indigenous communities in Nicaragua, particularly in the project area.In recent decades, the harsh local situation has only worsened because of organized crime, drug trafficking, the expansion of agriculture and cattle ranching, and the promotion of extractivist policies, as well as the lack of state protection.The investigation launched by the Independent Reparations Mechanism, which included field work and face-to-face and virtual interviews with all stakeholders, confirmed some of the allegations made in the complaint, including the lack of adequate consultation processes and the lack of free, prior, and informed consent of the affected communities. This is stated in the investigation’s final report.In July 2023, the Fund's Board of Directors, which was called upon to decide on the future of the project based on the Investigation Report, delegated the task to the Fund's Secretariat. As a result, neither the IRM nor the claimants had any further say in the matter.Finally, on March 7 of this year, the Secretariat announced its decision: to terminate the project's financing agreement, acknowledging that the developers had failed to comply with the Fund's policies, as alleged by the communities in the complaint."The decision is a valuable lesson for the Green Climate Fund, whose policies and safeguards exist to prevent these unfortunate situations and must be applied rigorously and consistently from the conception of projects seeking funding," said Ortúzar. Press contactVíctor Quintanilla (Mexico), AIDA, [email protected], +52 5570522107

Read more

Defending the Volta Grande do Xingu in the Brazilian Amazon

"Certain lives exist only in the Xingu River, mine is one of them. And also that of the indigenous and riverine peoples. Can these lives be destroyed?” The question posed by Sara Rodrigues Lima - a local river dweller, fisherman and researcher - highlights the paradox that one of the most biodiverse, ecologically, climatically and culturally important regions in the world is also one of the most affected by socio-environmental impacts. The Volta Grande (or "Big Bend") of the Xingu River, located in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon, is home to a unique ecosystem and is a key region for the conservation of global biodiversity. For centuries, it has been home to indigenous and riverine peoples who have shared ownership of the river and the Amazonian rainforest, providing sources of food, water, identity, culture and mobility, among other things. This link has translated into livelihood systems based on caring for and defending the territory and their own existence, which are now severely threatened. Since 2015, this region has been the target of large extractive projects that threaten the livelihoods and physical and cultural survival of traditional peoples and communities. This has been accompanied by violence against people defending this Amazonian territory. In order to deal with this situation, the affected peoples and civil society have created a network that unites and strengthens their efforts. The Alliance for the Volta Grande do Xingu, formed by social movements and organizations, including AIDA, supports and coordinates actions to defend the region as a living and healthy territory. The coalition has taken the case to the United Nations. The cumulative impact of two megaprojects One of these projects is the Belo Monte dam, whose construction has caused irreparable environmental damage and human rights violations for several generations. The drought caused by the diversion of the river to generate electricity, as well as the ineffectiveness of the mitigation measures implemented, have led to an ecological and humanitarian collapse in the Volta Grande. Currently, thousands of traditional families are suffering from the death of fish, extinction of fishing, lack of food security, impoverishment, physical and mental illnesses. Another major threat to the region and its traditional inhabitants is the Volta Grande project, where the Canadian company Belo Sun intends to build the largest open-pit gold mine in Brazil. The coexistence of the two projects poses the risk of overlapping areas of direct impact. In this scenario, the potential damage to the environment and to indigenous and riverine peoples will be irreversible. The Belo Sun project is proposed to be built less than 10 kilometers from the Belo Monte dam, on the banks of the Xingu River, in the midst of indigenous lands, protected areas and traditional communities. The magnitude of the synergistic and cumulative impacts of the mine and hydroelectric dam has not been assessed. Also ignored were technical analyses that pointed to the serious impacts of the use of cyanide, the contamination of the river, and the risks of a dam breach that, if it were to occur, would flood 41 kilometers along the river and reach nearby indigenous lands. In addition, the state excluded indigenous peoples, riverine and peasant communities from the environmental licensing process for the mining project. Because they live outside the demarcated indigenous lands or more than 10 kilometers from the project, some indigenous peoples were not considered affected or consulted about the implementation of the project. The lack of consultation and public participation of indigenous and riverine peoples led Brazilian courts to order the suspension of the mining company's operating license. Violence and threats against human rights defenders The arrival of Belo Sun in the area is a serious intervention in the socio-cultural environment of the Volta Grande do Xingu. The overlapping of the mining project in a territorial polygon inhabited by traditional peoples, rural groups benefiting from the agrarian reform, and artisanal miners has led to community divisions and violence against those who oppose the mine. In the context of the project's development, there have been reports of illegal land purchase and sale contracts to evict rural families, threats to the area's inhabitants by private security companies, and violence against peasants claiming agrarian reform lands acquired by the mining company, which are the subject of legal proceedings. Threats of violence against environmental and human rights defenders have also increased in intensity and severity. Some of them have had to leave the area to protect their lives, and those who remain in the area face constant risks and threats. Defending the Volta Grande and its people before the United Nations One of the most important actions of the Alliance for the Volta Grande do Xingu has to do with advocacy in the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), a special process of periodic review of the human rights record of the 193 member states of the United Nations. At Canada's fourth UPR cycle in Geneva in August 2023, more than 50 civil society organizations and communities affected by Canadian business activities presented a report highlighting human rights abuses from 37 projects in nine countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, including Belo Sun's Volta Grande project. The document includes recommendations to ensure that states exercise effective environmental oversight that requires human rights due diligence on the part of companies operating in their territories. One of the defenders of the Volta Grande was part of the delegation in Geneva. In addition to denouncing the abuses suffered, he reported on the risks posed by the socio-environmental impact of the Belo Sun project. More than 20 countries and 13 permanent missions and UN agencies took note of the situation in the region. The results of Canada's fourth UPR cycle, released last month, include 34 recommendations directly related to the Alliance's report. Canada has not yet accepted these recommendations, but may do so at the next session of the UN Human Rights Council, which concludes on April 5. As a follow-up to the UPR advocacy, the Alliance submitted reports on the impact of the Belo Sun project to UN Special Rapporteurs. One of them, sent to the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, focuses on the situation of vulnerability and criminalization of human rights defenders. Similarly, the Alliance submitted a report to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights highlighting the human rights violations committed by Brazil in the Belo Monte and Belo Sun cases, as well as the lack of effective measures to require human rights due diligence by the companies responsible for these projects. Networking in these international spaces to expose the pattern of environmental impacts and human rights violations of extractive economic projects in Amazonian territories has been one of the alliance's strategies of resistance and denunciation. The conservation of the Amazon and the protection of its peoples are incompatible with the large-scale mining planned by Belo Sun. States have an obligation to prevent serious and irreversible damage to the environment and the population. In the case of Belo Sun, Brazil has the opportunity to avoid repeating the environmental tragedy of Belo Monte and to declare definitively that the mining project is unsustainable from a socio-environmental point of view. The road to these demands and the achievement of these goals will be full of challenges and struggles. But courage and resisting are inherent to those who live in and defend the Amazon. The defense of the Xingu River Basin as a free, vibrant, healthy and safe territory for its peoples and its defenders is an urgent call for social mobilization for the social-ecological protection of one of the world's most important ecosystems.

Read more

Forest fires: How can we help prevent them?

The recent huge fire in the Valparaíso region of Chile has been described as the country's biggest disaster since the 2010 earthquake. But this year, as in previous years, forest fires and their deadly consequences are not an isolated phenomenon in Latin America. In Colombia, the fires forced the government to declare a national disaster and prompted civil society to call for comprehensive protection of Colombia's forests and páramos. Fire also reached part of Argentina's Patagonia region. Ninety percent of forest fires are caused by humans, particularly through activities such as logging and slash-and-burn agriculture. The climate crisis is contributing to their greater intensity and frequency, increasing the risks to forests, species and communities. In addition, wildfires affect air quality and thus human health If this situation is the result of our actions, it is also in our hands to prevent it. What can we do to prevent fires? Here are some actions that different actors in society can take to contribute to this important task. What can governments do? Design and implement laws to ensure forest security and ensure compliance with existing laws. Develop education campaigns to raise public awareness of the importance of forests and how to care for them. Strengthen fire prevention and suppression infrastructure, including spray planes, containment barriers, and technology to constantly monitor the health of forests. What can businesses do? Reduce emissions of gases that heat the atmosphere and increase the risk of wildfires by switching to cleaner energy sources. If flammable waste is generated, implement policies to dispose of it responsibly. Train their work teams to respond to these types of disasters. Promote best practices that help protect the environment. What can citizens do? Organize garbage collection groups and avoid making campfires and/or practicing livestock and agricultural activities in the forest. Obtain and disseminate quality information about the importance of these ecosystems for life on the planet. Follow safety instructions, such as wearing masks and/or evacuating smoke-contaminated areas. Be vigilant and make sure we know how to report fires and what action plans are in place to protect our nearby forests. It is essential that governments, businesses and citizens work as a team to protect forests and promote a culture that cares for the environment and all life.

Read more