Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

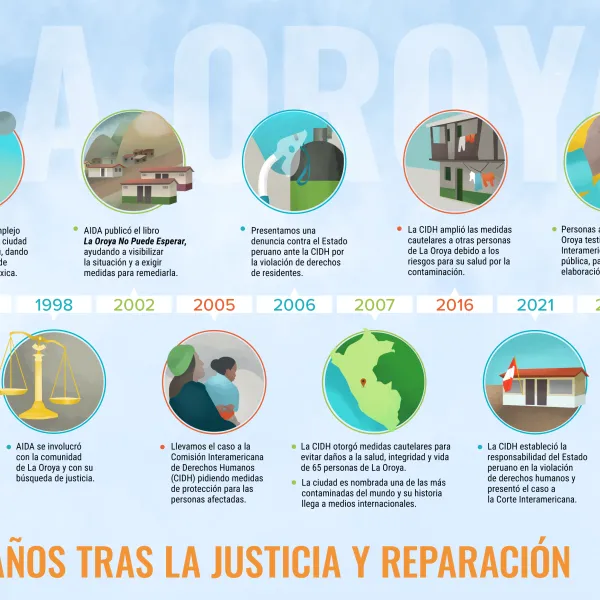

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

International technical assistance is consolidated to recover Uru Uru and Poopó lakes

At the request of organizations and communities, experts from the Ramsar Convention Secretariat will evaluate the degradation of the lakes and then issue technical recommendations for their recovery. Oruro, Bolivia. From October 11 to 15, a team of experts from the Ramsar Convention Secretariat will visit the Uru Uru and Poopó lakes, located in the central-eastern part of the Bolivian altiplano, to conduct a technical analysis of their degradation and then provide concrete recommendations to the Bolivian State for the recovery of the ecosystems. In July 2019—as part of the #LagoPoopóEsVida campaign—local communities and environmental, social and women's organizations sent the Ramsar Secretariat information on the state of the lakes and requested technical assistance to assess their health. The Bolivian government then made the formal request to make the visit feasible. "We recognize the political will of national authorities to obtain international support for the environmental crisis facing the lakes, on whose preservation the livelihoods of peasant and indigenous populations depend," said Claudia Velarde, an attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). "Ramsar Advisory Missions are an effective tool offering independent and specialized advice geared toward the preservation of wetlands." Poopó is the second largest lake in Bolivia. In 2002, in order to preserve its biodiversity—which includes endemic and migratory birds and the largest number of flamingos in South America—Poopó and Uru Uru were declared a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention, an intergovernmental treaty for the protection of these natural environments. "The Uru Uru and Poopó lakes guarantee the recharging of wells and other water sources, regulate the climate, provide habitat for birdlife, food security and sovereignty for surrounding populations, and shelter millenary cultures," said Limbert Sánchez, of the Center for Ecology and Andean Peoples (CEPA). Several factors have led to the catastrophic situation currently facing Lake Poopó, including: mining activities, which have not stopped during the pandemic and permanently generate acidic water and tons of mining waste; the diversion of tributaries like the Mauri River; the fact that the TDSP (Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopó-Salar Water System) is not guaranteeing water for the entire basin; and the climate crisis. Cumulatively, these situations have damaged the lake and placed the life systems that depend on it at risk. "In December 2015, the water levels of Lake Poopó were completely reduced, one of the biggest environmental catastrophes in the country. Currently, what is left of the water mirror is minimal compared to historical records," corroborated Yasin Peredo, of the Center for Andean Communication and Development (CENDA). In addition to causing serious environmental damage, what’s happening to Lakes Poopó and Uru Uru is a serious violation of surrounding communities’ rights to water, health, territory, food and livelihood. "It’s with great sadness that we witness the disappearing of Lake Poopó, and the risk to our Lake Uru Uru," said Margarita Aquino, coordinator of the National Network of Women Defenders of Mother Earth (RENAMAT). "Mining contamination is stripping us of our water sources and is violating the rights of us women and our communities." Indigenous Aymara and Quechua communities depend on the health of these ecosystems, as do the Uru Murato, one of Bolivia's oldest native nations. The members of this millenary culture once lived from fishing, but the contamination of Poopó and its scarce water supply has forced them to migrate in search of other ways to survive. Don Pablo Flores, a native authority of the Uru de Puñaca community explains: "In August, authorities arrived and with them we went to the lake and found that there is no more water; the Panza Island sector is also dry. As Urus, how are we living? Before we used to go for parihuanas [Andean flamingos], but not now. In February they used to lay eggs and change their feathers. This year there are none. The flamingos are dead. The lake does not exist now. The three Uru communities are suffering; we used to live from hunting and fishing. We ask the municipal, departmental and national authorities for more attention because, so far, practically nothing has been done to save, protect and recover our lake Poopó." By including the Uru Uru and Poopó lakes as a Ramsar site, the Bolivian State committed itself to conserving the ecological characteristics of these wetlands. In this sense, the visit from the mission of experts is a key opportunity to obtain objective and specialized recommendations aimed at fulfilling this commitment. "Environmental organizations, communities and the people of Bolivia are awaiting the visit of the Ramsar Mission. We believe that the current situation of the ecosystem must be taken into account, but also the factors that continue to influence its degradation. As long as strategies to combat climate change are not adopted, mining pollution is not stopped, and the amount of water needed for the entire TDPS is not guaranteed, the critical situation of our Uru Uru and Poopó lakes cannot be reversed," said Ángela Cuenca, coordinator of the CASA Collective. PRESS CONTACTS: Victor Quintanilla (MExico), AIDA, [email protected], +5215570522107 Angela Cuenca (Bolivia), Colectivo CASA, [email protected], +59172485221 Limbert Sanchez (Bolivia), CEPA, [email protected], +59172476802 Sergio Vasquez Rojas (Bolivia), CENDA, [email protected], +59172734594

Read more

¡Gracias totales!

I’m ending an era of 18 great years at AIDA, my second home. Words are not enough to describe how grateful, proud and happy I feel as I take stock of the achievements, progress and lessons learned. I treasure the wonder of meeting and sharing this journey with so many people in every corner of our Americas and beyond; the blessing of traveling rivers, mountains and territories and learning with and from each and every person and community. For all of this, I can only say: ¡Gracias totales! This has been the work of my dreams and the great honor of my life: to be able to build and lead this organization, alongside great people, building community from our female leadership, contributing throughout the continent to the protection of territories, rights and the environment. I am deeply grateful for the company, support, mentorship, inspiration, and sisterhood of Anna Cederstav, with whom I shared the dream and leadership of AIDA during this time, and who will continue in the organization supporting the new executive leadership. It is impossible to imagine a better co-director. Infinite thanks also to the Board of Directors for their trust and continued support. It is great to know that the organization has your back to ensure its growth and transcendence in these times of change. To each of the people of my current team and of all these years, words cannot express my admiration and deep gratitude for their invaluable commitment, professionalism, love and dedication. The results achieved are thanks to you all. It is very gratifying to have contributed to important advances in the region, including making visible and supporting the fights for justice in La Oroya, Peru, and in the Xingu River basin in Brazil; helping to protect the San Pedro Mezquital and Papagayo rivers in Mexico, the páramos in Colombia, the corals and mangroves on our coasts; conserving turtle nesting areas such as Las Baulas in Costa Rica; helping improve the Constitution in Mexico; helping include human rights in climate agreements and improving standards to protect rivers and mangroves; helping improve the safeguards of some international financial institutions; and contributing to the advancement of jurisprudence in the Inter-American System, including the recognition that climate change impacts human rights. It has been even more gratifying to have achieved all this together with great people both in our team and in various organizations, networks, communities and national and international entities. Today especially, and in view of the climate crisis and the reality of our region, it is essential to continue advancing in the collective work with and from the territories, motivating the diversity of knowledge and seriously including the perspective of women, youth and communities to reach the solutions that have so far proved elusive. This has all been a learning experience, because each achievement has been the result of close coordination, and of the diverse and complementary contribution of multiple visions. I am confident that this perspective will continue to be strengthened in order to make further progress towards finding solutions for our collective challenges. The magnitude of the climate and biodiversity crisis, the imperative need for a transformative recovery, and effective protection of human rights defenders, the environment and territory are three priorities that require our best efforts and impact. It is comforting to know that we have helped strengthen and build a great regional and global community with whom we share the goal of advancing the outcomes that people, communities, nature, and our societies and countries so desperately need. It is one of my greatest rewards after so many years of work. For all these reasons, and given that the only constant in life is change, the time has come to give free rein to new leadership. This decision has been difficult because this has been my home for so long. I first heard about AIDA in July 1997, when the organization was still in its infancy and I was studying law and working at Fundepúblico in Colombia. Upon learning of their intention to work on public interest environmental law in and from Latin America, I knew immediately that it was my place. I started as an intern in May 2003 and, a few months later, the Board of Directors hired me as an attorney. My heart did not fit in my chest and the ideas did not stop running through my mind. Today I have the satisfaction of having done my best to make a positive contribution to my region, putting law and science at the service of people, communities and the environment. In the process, I was also able to grow as a lawyer, and a leader, while building my family and becoming a wife and mother. After countless adventures, learning, successes and failures, it is time to embark on other paths and embrace change. I will continue to contribute to the understanding of the climate crisis and especially to identify how we can move towards climate justice with and from a feminist perspective and from the South, of course. We will continue to share this path towards climate and environmental justice, which is also social. I reiterate my deepest gratitude for so many lessons learned, opportunities and achievements. I am confident that AIDA is in the best hands and ready to move on to an exciting new stage.

Read more

The IPCC's Sixth Report: the stark reality we must face with agency and hope

“Adults keep saying: “We owe it to the young people to give them hope.” But I don’t want your hope. I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act”. - Greta Thumberg, addressing the World Economic Forum in January 2019. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report confirmed what we’ve all feared. With more refined scientific evidence than ever before, the report warns that climate change is intensifying, affecting all regions of the planet. Humanity's influence on this imbalance is now referred to as "unequivocal." As such, there’s no doubt that it’s our responsibility to confront the problem. Recent and aggressive climate events demonstrate that the world is transitioning from mere warnings to real, apocalyptic experiences. The Panel is not exaggerating. Over the last few months, floods have killed hundreds of people in some of the richest countries on the planet, and fires have ravaged thousands of hectares across the globe. Despite all this, there is still hope! And hope is our main ally in changing course. The report projected five scenarios, from the least to the most ambitious, according to the mitigation measures that humanity could implement. All of them, even the most ambitious, result in exceeding the 1.5 °C average temperature of the planet by 2040. Despite the starkness of that forecast, the report also shows that, by taking aggressive action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we could stabilize the increase at 1.4°C by 2100. The battle is not over, let alone lost. The most important consequences of this planetary imbalance are still uncertain and are being played out in the field. So what’s next? Drastic reductions of greenhouse gases will only be possible with systemic changes at the government and corporate levels. We also need to adjust our narratives so as to not fall into defeatism and hopelessness, because there is no scientific evidence to support surrender. Nor should we allow the environmental movement to become divided; we must be alert to the campaigns of fear and diversion practiced by our opponents. Hopelessness, defeatism and the division of our voices are precisely the winning cards of those who resist change. Given the global context, what follows are some necessary and urgent actions that will allow us to advance toward the future we need: Aiming for a rapid and just energy transition that respects human rights and includes a gender focus; as well as a new type of development that does not bulldoze nature, but cherishes and respects it. These changes should not produce fear. The technology to generate energy with minimal emissions and environmental impacts exists, is proven, and has greater potential to create jobs than the fossil fuel industry. A world powered by clean, renewable energy is a fairer, greener world. Holding the industries and companies that drive our economy accountable for what their activities leave behind. The subsidy nature has paid in the name of economic development has already exceeded what is reasonable. Projects that impact the environment, that attack the balance of nature, are no longer viable. The institutional framework and the principles of national and international law that protect the environment and human rights are on our side. We must interpret and use them for what they are: sources of binding and obligatory law. Ensuring the protection of natural sites that have not yet been disturbed, especially those of high environmental value. Nature has the capacity to regenerate and heal itself, but we must give it a chance. Indigenous and traditional peoples, guardians of their forests and territories, play a key role in this. Advocating for the correct use of climate funds at the international level, ensuring that they work toward climate justice and not false solutions that do more harm than the disease itself. National and international financial institutions move huge amounts of money each year to address climate change. Funds for mitigation and adaptation are available and projects to be financed must comply with environmental and social safeguards. The monetary cost of not acting or not acting enough is much higher than the cost of taking immediate, effective and decisive action. Being strategic and relying on science to take advantage of every mitigation opportunity. One example is the reduction of short-lived climate pollutants, which were specifically addressed in the recent IPCC report. These pollutants have historically lacked the attention they deserve, despite the incredible opportunity their mitigation implies. One of them is methane, whose presence in the environment is at an all-time high. Methane—the sources of which include coal mining, fracking, large dam reservoirs and intensive livestock farming—has 67 times more power than carbon dioxide (CO2) to warm the planet over a 20-year period, and its emissions cause almost 25% of that warming. Reducing these pollutants also means improving air quality in cities across the global. Achieving ambitious results in international negotiations and honoring the treaties that protect the planet, taking advantage of the strength we have when we act in coordination. It’s true that we have been attending UN conferences on climate change for 25 years without managing to reduce emissions, but it’s also true that we have an agreement signed by all member states that is binding and that orders each country to do its part to avoid exceeding the dangerous barriers of warming. Let us not dismiss what has been achieved; rather, let’s continue to build on it. We must demand these actions and not settle for less. We must be on alert to vote for leaders who have what it takes to lead us that way. Every small victory, every ton of CO2 that is kept in the ground, every natural space that is preserved, moves us away from the worst effects of this crisis. It's our turn, and nature must come first. We owe it to those who will inhabit this beautiful planet in the near and distant future.

Read more