Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

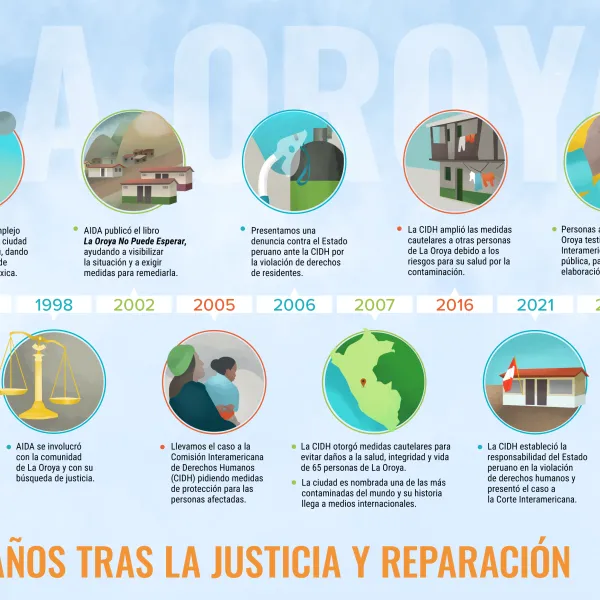

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

3 ways to maintain hope in the face of the climate crisis

Those of us who work on environmental issues are bombarded on a daily basis with headlines repeating the message: “Time is up, our days are numbered.” And, to tell the truth, rarely do they seem exaggerated: the IPCC reports, fires in Australia, the disillusionment of COP25, the mocking of the youth movement, assassinations and threats to environmental defenders. During dinner parties and casual get-togethers, people who know I work on environmental issues ask me what they can do for our planet. We start by talking about garbage: produce less of it. This, although seemingly basic, leads to long and heated conversations. Why? Because it questions our means of consumption, how we transport ourselves, feed ourselves, and dress. It makes us analyze our lifestyle and ask ourselves what “quality of life” means for us. Our garbage, after all, is the result of a long chain of emissions, which include the exploitation of land, species, and people. The truth is, everything is connected and it’s impossible to detach ourselves from our impact on the Earth. It’s through this chain of thoughts that many of us fall into episodes of “eco-anxiety.” It’s an increasingly common condition that, if left untreated, can be detrimental to our health. In 2017 the American Psychological Association (APA) described eco-anxiety as “a chronic fear of environmental doom… Watching the slow and seemingly irrevocable impacts of climate change unfold, and worrying about the future for oneself, children and later generations.” The strange thing about this condition is that it can stop us from acting. We might begin to believe there’s nothing we can do and, then, stop paying attention. We might become more lax with our consumption habits and end up aggravating the problem. So what can we do? From what I’ve gathered, our actions can be divided into three areas: the individual, the community, and the citizen-consumer. First things first: Be good to yourself A general rule for helping others is to first help yourself. The climate crisis affects our physical health, food security, human rights, and mental health. According to the APA, emotional responses are normal and negative emotions are necessary for making decisions and living a full life. But extreme emotions and the lack of a plan to resolve the problem can interfere with our ability to think rationally and behave appropriately. Not to mention the fact that those suffering losses due to environmental catastrophes (hurricanes, droughts, and floods) may develop post-traumatic stress. To confront these emotions, the APA suggests that we: Believe in our own resilience and know that we can overcome obstacles. Practice optimism and learn from our experiences. Cultivate self-regulation and emotional self-awareness in order to develop long-term strategies; knowing how to detect them prevents episodes from worsening. Find meaning in your life. Faith or religion work for some; for others it’s meditation or building community. The point is to find something that gives you a sense of peace. Individual actions do help, and people united for a cause can make a difference. Rather than punish ourselves for everything that we can’t do, let’s begin to talk about what we can. How many emissions can we cut back on by riding a bicycle? How many plastic bags can we divert from the sea? How does our consumption help the local economy and our environment? And always, always, take a daily dose of nature to inspire yourself. Second: Your immediate circle Recently, single-use plastic bags were banned in Mexico City. More than one person said that it violated their right to shop as they please; others complained they didn’t know how to shop anymore. I’ve used cloth bags for years. I could have just rejoiced in my own environmental righteousness and bragged on Twitter. Instead I asked myself, “Why not share some recommendations?” Practices that I had already applied to my house were well received by friends and neighbors because they were practical. Building relationships, however brief, is a step toward strengthening our community. Also, it helps to maintain perspective and a sense of humor. Get together with neighborhood groups, volunteer with organizations whose cause you support. Donating time, money, or materials is taking a step beyond your individual actions. Have a friend who wants to eat less meat? Offer them your best vegetarian recipes! Do you know how to program or do graphic design? Do you have a pick up truck? Surely there are groups who would appreciate your help. At AIDA, for instance, we’re often looking for volunteers and interns. The APA recognizes the impacts of the climate crisis on the mental health of certain communities; they are not the same in a city as they are in an area at risk of environmental disaster, or in an indigenous community. Affected communities confront a loss of social cohesion and the loss of important spiritual or recreational places. They also witness an increase in violence, including racial violence, as certain groups become increasingly persecuted. Furthermore, a loss of identity ruptures the unity of these communities, as is happening with the Inuit of Greenland or as we at AIDA have seen in displaced indigenous and riverine populations in the Amazon. Third (I’m sorry): We have to talk about politics and civic engagement This may be a subject you don’t particularly enjoy, but you’re needed here too. The wastewater produced in your home is but a drop compared to untreated industrial waste being dumped into a river. You could ride your bike everyday, but you would still be living in a country that permits industries to emit volatile carcinogenic and greenhouse gases into the atmosphere without accountability. While our goodwill does matter, it just doesn’t have as large an impact as the will (and obligations) of governments and industries to do things right and work for the health of all living things. In Latin America, the election of our local representatives may work differently than it does in the United States. But that doesn’t free us from the responsibility to elect representatives that will work for a cleaner and more resilient future. Indeed, we must demonstrate our interest in that future and demand that they work toward it. Environmental writer Emma Marris explained it well in her New York Times column: “The climate crisis is not going to be solved by personal sacrifice. It will be solved by electing the right people, passing the right laws, drafting the right regulations, signing the right treaties—and respecting those treaties already signed, particularly with indigenous nations. It will be solved by holding the companies and people who have made billions off our shared atmosphere to account.” The balance we’re seeking in AIDA We are proud to be an organization made up of professionals who are deeply passionate about the environment. On a personal level, we share our ideas with each other about how to create a better planet. On a community level, we all support the organization, and there are also those of us that organize civic and neighborhood events. On the level of public policy and participation, AIDA works for environmental justice. We empower communities with the knowledge and tools they need to safeguard and monitor their rights. We take emblematic cases to court and before international bodies to ensure that companies and governments live up to their obligations. We believe that a healthy and equitable future is possible.

Read more

3 ways to maintain hope in the face of the climate crisis

Those of us who work on environmental issues are bombarded on a daily basis with headlines repeating the message: “Time is up, our days are numbered.” And, to tell the truth, rarely do they seem exaggerated: the IPCC reports, fires in Australia, the disillusionment of COP25, the mocking of the youth movement, assassinations and threats to environmental defenders. During dinner parties and casual get-togethers, people who know I work on environmental issues ask me what they can do for our planet. We start by talking about garbage: produce less of it. This, although seemingly basic, leads to long and heated conversations. Why? Because it questions our means of consumption, how we transport ourselves, feed ourselves, and dress. It makes us analyze our lifestyle and ask ourselves what “quality of life” means for us. Our garbage, after all, is the result of a long chain of emissions, which include the exploitation of land, species, and people. The truth is, everything is connected and it’s impossible to detach ourselves from our impact on the Earth. It’s through this chain of thoughts that many of us fall into episodes of “eco-anxiety.” It’s an increasingly common condition that, if left untreated, can be detrimental to our health. In 2017 the American Psychological Association (APA) described eco-anxiety as “a chronic fear of environmental doom… Watching the slow and seemingly irrevocable impacts of climate change unfold, and worrying about the future for oneself, children and later generations.” The strange thing about this condition is that it can stop us from acting. We might begin to believe there’s nothing we can do and, then, stop paying attention. We might become more lax with our consumption habits and end up aggravating the problem. So what can we do? From what I’ve gathered, our actions can be divided into three areas: the individual, the community, and the citizen-consumer. First things first: Be good to yourself A general rule for helping others is to first help yourself. The climate crisis affects our physical health, food security, human rights, and mental health. According to the APA, emotional responses are normal and negative emotions are necessary for making decisions and living a full life. But extreme emotions and the lack of a plan to resolve the problem can interfere with our ability to think rationally and behave appropriately. Not to mention the fact that those suffering losses due to environmental catastrophes (hurricanes, droughts, and floods) may develop post-traumatic stress. To confront these emotions, the APA suggests that we: Believe in our own resilience and know that we can overcome obstacles. Practice optimism and learn from our experiences. Cultivate self-regulation and emotional self-awareness in order to develop long-term strategies; knowing how to detect them prevents episodes from worsening. Find meaning in your life. Faith or religion work for some; for others it’s meditation or building community. The point is to find something that gives you a sense of peace. Individual actions do help, and people united for a cause can make a difference. Rather than punish ourselves for everything that we can’t do, let’s begin to talk about what we can. How many emissions can we cut back on by riding a bicycle? How many plastic bags can we divert from the sea? How does our consumption help the local economy and our environment? And always, always, take a daily dose of nature to inspire yourself. Second: Your immediate circle Recently, single-use plastic bags were banned in Mexico City. More than one person said that it violated their right to shop as they please; others complained they didn’t know how to shop anymore. I’ve used cloth bags for years. I could have just rejoiced in my own environmental righteousness and bragged on Twitter. Instead I asked myself, “Why not share some recommendations?” Practices that I had already applied to my house were well received by friends and neighbors because they were practical. Building relationships, however brief, is a step toward strengthening our community. Also, it helps to maintain perspective and a sense of humor. Get together with neighborhood groups, volunteer with organizations whose cause you support. Donating time, money, or materials is taking a step beyond your individual actions. Have a friend who wants to eat less meat? Offer them your best vegetarian recipes! Do you know how to program or do graphic design? Do you have a pick up truck? Surely there are groups who would appreciate your help. At AIDA, for instance, we’re often looking for volunteers and interns. The APA recognizes the impacts of the climate crisis on the mental health of certain communities; they are not the same in a city as they are in an area at risk of environmental disaster, or in an indigenous community. Affected communities confront a loss of social cohesion and the loss of important spiritual or recreational places. They also witness an increase in violence, including racial violence, as certain groups become increasingly persecuted. Furthermore, a loss of identity ruptures the unity of these communities, as is happening with the Inuit of Greenland or as we at AIDA have seen in displaced indigenous and riverine populations in the Amazon. Third (I’m sorry): We have to talk about politics and civic engagement This may be a subject you don’t particularly enjoy, but you’re needed here too. The wastewater produced in your home is but a drop compared to untreated industrial waste being dumped into a river. You could ride your bike everyday, but you would still be living in a country that permits industries to emit volatile carcinogenic and greenhouse gases into the atmosphere without accountability. While our goodwill does matter, it just doesn’t have as large an impact as the will (and obligations) of governments and industries to do things right and work for the health of all living things. In Latin America, the election of our local representatives may work differently than it does in the United States. But that doesn’t free us from the responsibility to elect representatives that will work for a cleaner and more resilient future. Indeed, we must demonstrate our interest in that future and demand that they work toward it. Environmental writer Emma Marris explained it well in her New York Times column: “The climate crisis is not going to be solved by personal sacrifice. It will be solved by electing the right people, passing the right laws, drafting the right regulations, signing the right treaties—and respecting those treaties already signed, particularly with indigenous nations. It will be solved by holding the companies and people who have made billions off our shared atmosphere to account.” The balance we’re seeking in AIDA We are proud to be an organization made up of professionals who are deeply passionate about the environment. On a personal level, we share our ideas with each other about how to create a better planet. On a community level, we all support the organization, and there are also those of us that organize civic and neighborhood events. On the level of public policy and participation, AIDA works for environmental justice. We empower communities with the knowledge and tools they need to safeguard and monitor their rights. We take emblematic cases to court and before international bodies to ensure that companies and governments live up to their obligations. We believe that a healthy and equitable future is possible.

Read more

Why are women so important to the pursuit of environmental justice?

Women have long played a fundamental role in the conservation and defense of the planet. Past and present struggles for environmental justice and the defense of animals have been, to a large extent, led by women. Yet the close relationship between women and the environment has not escaped the inequalities that characterize today’s societies. Poverty, exclusion, and inequality are intertwined with environmental degradation and the climate crisis. Women, in general, suffer these plagues in a differential and aggravated manner. In natural disasters, for example, women often experience higher mortality rates than men. Due to the role women play in their communities, they are often less equipped with mechanisms to help them respond to emergencies that result from disasters. They are less likely to know how to swim or climb trees. They are more likely to be responsible for young children or older members of the family. They are more likely to wear clothing that makes it difficult to quickly react to a crisis situation. Furthermore, for historical and cultural reasons, women are less likely to have access to information or be able to participate in situations that affect their right to a healthy environment. They also are less likely to have access to the mechanisms for addressing injustices or repairing damages from catastrophes. Women who do take on roles in the public sphere, participating in public issues, are more likely to take on additional responsibilities that, generally, a man in the same situation would not have to assume. And, at the same time, they confront more intense risks and greater obstacles to the development of their leadership. In this context, the gender focus—defined as the mechanism developed to guarantee holistically valuing the impact any action has on men, women, and those who identify between those categories—is fundamental to making asymmetries visible, overcoming barriers of discrimination, and removing scenarios of exclusion that impede women’s ability to enjoy their right to equality. The gender focus seeks to ensure that those challenges are included in the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of each intervention on a political, economic, and social level. The gender perspective is indispensable to empowering the leadership of women, which is proving increasingly vital in the struggle for environmental justice. In effect, the development of ecofeminist theories offers the world new and transformative alternatives to the ways of thinking that are bringing about the destruction of our environment and negatively affecting the lives of men, women, and other living things. Women are more than simply the most affected by the climate crisis. They also are active participants with a vital role to play in preserving nature and seeking solutions for the health of our planet.

Read more