Project

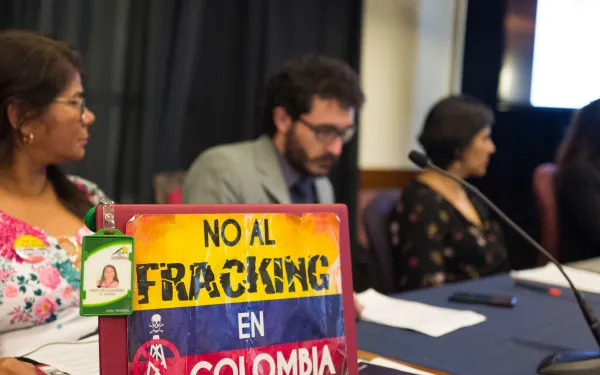

Foto: Andrés ÁngelStopping the spread of fracking in Latin America

“Fracking” is short for hydraulic fracturing, a process used to extract oil and natural gas from historically inaccessible reservoirs.

Fracking is already widespread in the global North, but in Latin America, it is just beginning. Governments are opening their doors to fracking without understanding its impacts and risks, and without consulting affected communities. Many communities are organizing to prevent or stop the impacts of fracking, which affect their fundamental human rights. But in many cases they require legal and technical support.

What exactly is fracking, and what are its impacts?

A straight hole is drilled deep into the earth. Then the drill curves and bores horizontally, making an L-shaped hole. Fracking fluid—a mixture of water, chemicals, and sand—is pumped into the hole at high pressure, fracturing layers of shale rock above and below the hole. Gas or oil trapped in the rock rises to the surface along with the fracking fluid.

The chemical soup—now also contaminated with heavy metals and even radioactive elements from underground—is frequently dumped into unlined ponds. It may seep into aquifers and overflow into streams, poisoning water sources for people, agriculture, and livestock. Gas may also seep from fractured rock or from the well into aquifers; as a result, water flowing from household taps can be lit on fire. Other documented harms include exhausted freshwater supplies (for all that fracking fluid), air pollution from drill and pump rigs, large methane emissions that aggravate global warming, earthquakes, and health harms including cancer and birth defects.

AIDA’s report on fracking (available in Spanish) analyzes the viability of applying the precautionary principle as an institutional tool to prevent, avoid or stop hydraulic fracturing operations in Latin America.

Partners:

Related projects

Latest News

The IPCC climate report: science has spoken and we must act now

The international scientific community has spoken: the only thing that can save us from a climate catastrophe is a radical and immediate change. The next 11 years are the most important in the history of the planet, in terms of climate change. Our response to their message will determine our future. In its most recent analysis, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of the United Nations establishes the impacts that could occur if the planet’s average temperature increases by more than 2°C, and compares those with what would happen if we stop warming, or at least keep it below 1.5°C. The 2016 Paris Agreement, an international accord to curb climate change, aims to keep warming well below 2°C with respect to pre-industrial levels, and to continue global efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. The impacts of global warming The IPCC experts’ conclusions are piercing. Those extra 0.5°C would be lethal for millions of people and their ways of life. If the Earth warms 2°C or more, we would experience: more frequent and intense heat waves, droughts and floods; sea level rise of an extra 10 centimeters, implying coastal flooding and filtration of salt water into agricultural areas and freshwater sources—a matter of life and death for roughly 10 million people; double the risk of habitat loss for plants and vertebrates, and triple the risk for insects, considering more than 100 thousand species which were studied; the disappearance of more than 99% of coral reefs, while 10 to 30 percent of what remains could be saved if we were to stabilize the planet’s temperature below 1.5°C; an increase in the range of mosquitoes that transmit diseases such as malaria and dengue; and the devastation of crops and livestock, severely affecting global food security. So, how are we doing now? Not so well. The planet has already warmed 1°C since preindustrial times, and in 2017 the emissions responsible for warming increased again. The commitments nations made to comply with the Paris Agreement are insufficient. Settling on that level of ambition would take us to 3°C warming by 2030, a reality with unimaginable consequences. Changing our climate destiny Let’s talk about solutions. Ensuring that the planet’s warming doesn’t exceed 1.5°C is possible, but it will require unprecedented action. Emissions must lower by 45 percent between 2010 and 2030, and we must achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. That means not emitting more than what the world’s forests and natural carbon sinks can absorb. This will require that: the most polluting industries, particularly those producing fossil fuels, implement radical changes; renewable energy is the norm by 2050, accounting for between 70 and 85 percent of total energy production; coal-fired power plants disappear; transportation runs with clean, renewable electricity; and we expand, maintain, and care for forests and other natural carbon sinks, which are responsible for removing emissions from the atmosphere. The IPCC report also recognizes a monumental opportunity: the mitigation of short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs)—including black carbon or soot, methane, hydrofluorocarbons and tropospheric ozone. More climatically intense than carbon dioxide, SLCPs are responsible for half of global warming. Because of their short duration in the atmosphere, they could play a key role in reducing warming in the short term. In addition, the reduction of SLCPs brings important benefits for human well-being, including the reduction of pollution that affects public health and better yield of crops. But few countries have included the reduction of short-lived climate pollutants in their national commitments on climate change. At AIDA we’re working so that Latin American nations advance in the control of these emissions. As the region with the greatest potential for renewable energies, Latin America has the opportunity to be an example for the rest of the planet. The threats facing the region are great and avoiding them is well worth the effort. Climate change threatens to shake us from our very roots—melting Andean glaciers, increasing droughts and floods, diminishing freshwater supplies, driving species to extinction, increasing wildfires, favoring the spread of invasive species, losing corals and marine biodiversity, affecting food security, and wreaking havoc on people’s health and livelihoods. The outlook is clear: maintaining global warming below 1.5°C is not an easy task, but science holds it’s possible. We have the scientific knowledge, and the technological and financial capacity to achieve this goal. The responsibility now lies with governments, decision-makers and the private sector—together they must drive unprecedented changes. We must remember that implementing these changes is not just possible, it’s desirable. A world with fewer emissions is a cleaner and a fairer world for us and for future generations. What’s not to like?

Read more

Civil society warns Inter-American Commission of human rights violations caused by fracking in Latin America

Boulder, Colorado. Representatives of communities and organizations from across Latin America testified before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights this week on the impacts that hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has on human rights and the environment. The hearing—responding to a petition signed by more than 126 organizations from 11 countries of the Americas—was held in Boulder, Colorado this week as part of the Commission’s 169th period of sessions. The principal requests to the Commission, and the Rapporteurs from various countries, were to urge the States to adopt efficient and opportune measures to prevent human rights violations resulting from the exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons, and to apply the precautionary principal in the face of fracking’s environmental damages. “In Latin America, fracking been carried out without informing or adequately consulting the affected populations, thereby violating their right to information, participation, prior consultation and consent,” explained Liliana Ávila, Senior Attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). “Fracking’s demand for water competes with the use of water for human consumption, and the contamination it causes in the water, soil and air seriously impacts the right to a healthy environment and compromises the effective enjoyment of other rights—including a dignified life, personal integrity, health, food, water and adequate housing.” At the hearing, it was emphasized that women disproportionately suffer the impacts of fracking due to potential harm to their reproductive health, and since women are traditionally responsible for collecting water for use in their homes. Referring to the experience of the Mapuche communities of Argentina, Santiago Cané of the Environment and Natural Resources Foundation (FARN) stressed, “Fracking produces acts of violence against those who defend the environment and their rights.” “Institutionally, we can talk about the criminalization of social protest as one form of intimidation to eliminate the resistance to fracking projects,” he explained. “The prosecution of criminal cases against communities leaders that oppose the development of fracking has become an institutional media campaign that seeks to promote the idea that Mapuche communities are part of a terrorist group.” In Mexico, “specifically in the municipality of Papantla, Veracruz—which according to freedom of information requests is the city with the greatest number of fracking pools in the country—where the population is primarily the Totonac people, this exploitation technique has led to the diversion of springs and the drying up of artisanal wells. Many communities have lost their natural sources of water and have seen their health compromised and their living conditions deteriorate,” explained Alejandra Jiménez of the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking. Dorys Gutiérrez, of the Colombian organization Corporation for the Defense of Water, Territory and Ecosystems, noted that: “In Europe, 18 nations have applied the precautionary principle to prohibit or restrict this practice and in Australia, four of the eight territories have bans or moratoria in place. If fracking is so beneficial, why has it been so widely rejected in so many places?” According to data compiled by the Latin American Alliance on Fracking, roughly 5,000 fracking wells exist across the region. About 2,000 of those wells are found in Argentina; more than 3,350 are found in Mexico; and in Chile, according to official data, 182 wells have been approved, primarily for the island of Tierra del Fuego. Despite the technique’s expansion across the region, there has also been progress in banning or imposing restrictions on fracking in three states of the United States, in Uruguay, in the Argentine province of Entre Ríos, and in more than 300 municipalities in Brazil. Fracking’s advance is harmful to human rights, and represents a threat to the consolidation of the legal framework promoted by the Inter-American Human Rights System, which includes the obligations of States and the international protection of human rights and the environment. PRESS CONTACTS: Victor Quintanilla (MExico), AIDA, [email protected], +521 5570522107 Arturo Contreras (in Boulder, Colorado), +521 5533320505

Read more

Inter-American Commission to analyze fracking’s impacts on human rights

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights will hold an informative hearing on October 3, 2018 to better understand the situation of fracking in the Americas and the human rights violations it’s causing. The hearing is being held in response to a request brought forth by 126 Latin American organizations, united in the Latin American Alliance on Fracking. The hearing will take place in Boulder, Colorado during the Commission’s 169th period of sessions. In it, human rights defenders and representatives of affected communities will present detailed information on the documented human rights impacts, as well as the potential risks, of fracking in Latin America. The Alliance seeks to propose a series of recommendations to the Commission and governments of the region in order to guarantee human rights when faced with the exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbon reserves. According to the hearing request, there are approximately 5,000 fracking wells throughout Latin America. In Argentina, there are roughly 2,000 wells. In Chile, according to official data, 182 wells have been approved, the large majority in Tierra del Fuego. In Mexico, there are more than 3,350 fracking wells, although the signatory organizations indicated there are challenges in terms of access to this information. In Brazil and Colombia, contracts have been signed that allow for exploration and exploitation. In Bolivia, prospecting and sample studies of unconventional deposits have begun. Organizations from Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay signed the request for a hearing before the Commission in July. “Fracking’s advance in Latin America is being carried out blindly because neither the chemicals used, nor their synergistic effects, nor the actual and potential risks, nor the effectiveness of mitigation measures are known with any certainty,” explained Claudia Velarde, attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). “What is known is the damage fracking causes to the environment, the quantity and quality of water, and the impacts it has on health and human rights.” While fracking is promoted across Latin America, various nations, states and provinces of Europe, the Americas and Oceania have banned the technique due to the negative impacts it has had on the environment and public health. The request to the Commission emphasizes, “none of the nations where fracking has been implemented have a comprehensive knowledge of the irreversible damage it causes to the environment and the lives of individuals and communities. However, abundant scientific evidence exists on fracking’s negative impacts due to the extensive use of the technique in the United States.” Follow news from the hearing with the hashtag #AméricaSinFracking PRESS CONTACT Victor Quintanilla, AIDA (Mexico), [email protected], +521 5570522107

Read more