Project

Foto: Andrés ÁngelStopping the spread of fracking in Latin America

“Fracking” is short for hydraulic fracturing, a process used to extract oil and natural gas from historically inaccessible reservoirs.

Fracking is already widespread in the global North, but in Latin America, it is just beginning. Governments are opening their doors to fracking without understanding its impacts and risks, and without consulting affected communities. Many communities are organizing to prevent or stop the impacts of fracking, which affect their fundamental human rights. But in many cases they require legal and technical support.

What exactly is fracking, and what are its impacts?

A straight hole is drilled deep into the earth. Then the drill curves and bores horizontally, making an L-shaped hole. Fracking fluid—a mixture of water, chemicals, and sand—is pumped into the hole at high pressure, fracturing layers of shale rock above and below the hole. Gas or oil trapped in the rock rises to the surface along with the fracking fluid.

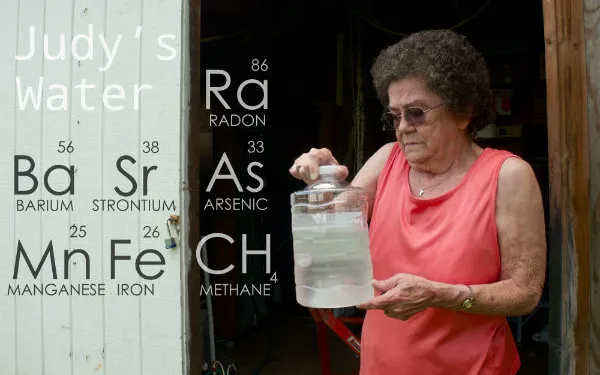

The chemical soup—now also contaminated with heavy metals and even radioactive elements from underground—is frequently dumped into unlined ponds. It may seep into aquifers and overflow into streams, poisoning water sources for people, agriculture, and livestock. Gas may also seep from fractured rock or from the well into aquifers; as a result, water flowing from household taps can be lit on fire. Other documented harms include exhausted freshwater supplies (for all that fracking fluid), air pollution from drill and pump rigs, large methane emissions that aggravate global warming, earthquakes, and health harms including cancer and birth defects.

AIDA’s report on fracking (available in Spanish) analyzes the viability of applying the precautionary principle as an institutional tool to prevent, avoid or stop hydraulic fracturing operations in Latin America.

Partners:

Related projects

Latest News

To cool the planet, fracking must be prohibited, organizations say

In the framework of COP21, a coalition of Latin American civil society organizations is urging world leaders meeting in Paris to ban fracking in their countries. By emitting large quantities of greenhouse gases, the process itself goes against the central objective of the climate negotiations: stopping global warming. Paris, France. In a public statement directed at Member States of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, organizations and allies of the Latin American Alliance On Fracking asked that all fracking activities be banned due to the fact that, among other impacts, hydraulic fracturing emits greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming. During the cycle of extracting, processing, storing, transferring, and distributing unconventional hydrocarbons using fracking, methane gas is released into the atmosphere. Methane is 87 times more powerful than carbon dioxide as an agent of global warming, the group explained in their statement. The document will be presented this Friday December 11 at 10 a.m. (local time) at the Climate Action Zone by: Alianza Mexicana contra el Fracking; Asociación Ambiente y Sociedad; the Inter-American Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA); Food & Water Watch; Freshwater Action Network Mexico; the Heinrich Böll Foundation – Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean; Instituto Brasileiro de Analises Socias e Economicas (IBASE); and Observatorio Petrolero Sur (OpSur). The organizations discuss the current state of hydraulic fracturing in Latin America. Although the use of the experimental technique is contrary to national and international commitments to reduce emissions, several countries in the region – among them Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Chile and Bolivia – have begun exploration or exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbons through fracking. “Fracking is advancing blindly in Latin America, with no comprehensive long-term studies on the risks and serious damage that it could cause to the health of people and the environment,” said Ariel Pérez Castellón, attorney at AIDA. “Operations of this kind in the region have failed to respect fundamental human rights, including the right to consultation and free, prior and informed consent; the right to participation and social control; and the right to information,” added Milena Bernal, attorney with the Asociación Ambiente y Sociedad. According to the organizations, fracking is advancing quickly into indigenous and rural communities, urban neighborhoods, and even Natural Protected Areas. It has caused the displacement both of people and of productive activities such as farming and agriculture, because their coexistence with this technique is impossible. Rejection of fracking has grown in parallel with its spread in operations. “The proof of this resistance are the national and international networks opposing this technique, including more than 50 municipalities that have banned it in Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay,” said Diego di Risio, researcher at Observatorio Petrolero Sur. “As part of our statement, we urge the Member Parties of the Convention to: sign a binding agreement that quickly and effectively reduces greenhouse gases and incorporates human rights into the legal text; apply the precautionary principle to ban fracking; and promote renewable energies and disincentivize the extraction of fossil fuels,” stated Claudia Campero Arena, researcher at Food & Water Watch, and Moema Miranda, director of Ibase. Read the full statement from the Latin American Alliance on Fracking here. Event “The fight against fracking in Latin America: experiences in Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Brazil and Mexico” Simultaneous translation in English and French Friday December 11, 2015 Climate Action Zone Centquatre, 5 rue Curial, Paris (Métro Riquet)

Read more

France’s Fracking Ban: Lessons for Latin America

By Eugenia D’Angelo, former AIDA intern, @DangeloEugenia Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking—the process of drilling into rock and injecting a mixture of water, chemicals, and sand under high pressure to fracture it and release oil and gas—is making headway around the world, causing increasing damage to the environment and human health. Even so, social movements have been effective at slowing governments and corporations interested in expanding the practice. One of the best examples can be found in France. The first country to ban fracking, it did so thanks to the pressure applied by French citizens. Having lived in France for four years, I can attest first-hand to the strength and importance of social movements throughout the process. The Legal Process The ‘Jacob Law’ (named for Minister Christian Jacob, who presented it) was approved[1] in 2011, during Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidency. It prohibits fracking for exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons. Later, taking advantage of division in the Socialist Party, oil companies found the help necessary to present a constitutional challenge to the fracking ban. On October 11, 2011, however, the Constitutional Council reaffirmed the validity of the ‘Jacob Law,’ stating that it complies with all constitutional principles. France became the first country in the world to turn its back on the controversial practice. Making A Difference Civil society and green political parties played a paramount role in France. French citizens overwhelmingly said “No!” to fracking,[2] with more than 80% voicing their opposition[3] (this compares to 47% in the United States, according to the latest Pew Research Center poll[4]). In France, movements are grouped together in social collectives that unite the populations of different departments. These groups were organized to be present in every part of the country where energy companies had permits for the exploration and exploitation of shale gas and oil. They remained there for the entire legal and political battle, until the prohibition on fracking finally became reality. Some of the actions taken by the “No Fracking France” association include: During the famous and highly publicized Tour de France, they carried an anti-oil-and-shale-gas banner signed by thousands of people. In the final stretch of the Tour de France, they sent a climber to hoist the banner to the top of Mont Blanc. They held a press conference on the matter in the National Assembly. They organised various informative and scientific seminars for the mayors of affected communities. They produced a video explaining fracking to the deaf-mute community. They took their complaints to the members of Parliament. Resistance in Latin America In contrast, various countries in Latin America are opening their doors to fracking. In response to this troubling trend, AIDA is helping to facilitate and coordinate a regional group, made up of civil society organizations and academic institutions, created to generate information, stimulate debate, and join forces to prevent and stop the negative impacts of fracking in Latin America. At AIDA we consider it necessary for governments and civil society to apply the precautionary principle. Within the framework of this principle and its constitutional obligations, States of the region should adopt effective measures to prevent the risks and severe damage to the environment and human health that fracking can bring about. As long as there isn’t a guarantee that the risks and impacts of fracking can be effectively prevented and mitigated, this type of activity should not be permitted. Raising awareness amongst citizens and social movements is key. Countries in Latin America are obligated to generate public, truthful and impartial information about the characteristics, process and components of fracking, and about its long-term impacts. Our authorities must create plural and adequate spaces for civil society in the decision-making process about the future of fracking in our territories. If they don’t, we as citizens have the right and the obligation to engage and mobilize ourselves so that those who resist can hear us. [1] It was a closed vote in the senate with 176 votes in favour and 151 against. “Gaz de schiste: le Parlement interdit l’utilisation de la fracturation hydraulique”, Le Monde, 30/06/2011. Available at: http://www.lemonde.fr/planete/article/2011/06/30/gaz-de-schiste-le-parlement-interdit-l-utilisation-de-la-fracturation-hydraulique_1543252_3244.html [2] The Collectif 07 Stop Shale Gas and Oil said: “ …we should be proud of the efficiency of public mobilization which, although it has not won the war, has clearly won the battle. The commitment of millions of citizens, in our department and in the whole of France, that they demonstrated every day, resisted, informed, organized themselves, mobilized themselves…sometimes with the participation of the mayors…has borne fruit. It is a test that gives hope for the fight to come…” See: “Gaz de schiste: la mobilisation citoyenne a gagné une victoire, mais pas la guerre.” Bourg Socialisme avenir. Available at: http://www.bsavenir.fr/2011/10/01/gaz-de-schiste-la-mobilisation-citoyenne-a-gagne-une-victoire-mais-pas-la-guerre/ [3] This percentage is higher than that against nuclear energy (the primary source of energy in France) according to: Chu, Henry. “Pressure builds against France’s ban on fracking,” Los Angeles Times, 22/06/2014. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-france-fracking-20140622-story.html#page=1 [4] http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2014/11/13/3591891/pew-poll-voters-oppose-fracking/

Read more

Stopping Fracking: Together We’re Stronger!

It’s an increasingly recognized reality: the world cannot burn its reserves of fossil fuels and expect the planet to be habitable. But energy companies continue extracting fossil fuels in pursuit of near-term profit, rather than adapting their business models for the sake of long-term sustainability. Already, much of the world’s reserves of easily extracted, high-quality fossil fuels have been exhausted. New horizontal drilling technology, combined with hydraulic fracturing (fracking), has made exploitation of hard-to-reach ("unconventional") oil and gas deposits possible. For a variety of reasons, fracking poses very high risks to public health and the environment. AIDA has begun working with civil society organizations and institutions to generate information, stimulate debate, and join forces to prevent the negative impacts of fracking in Latin America. The Risks of Fracking Fracking for unconventional deposits involves drilling into the ground vertically, to a depth below aquifers, and then horizontally through layers of shale rock. Then fracking fluid (a high-volume mixture of water, sand, and undisclosed chemicals) is injected at very high pressure to fracture the shale, thus releasing the oil and gas trapped inside. After fracking fluid surfaces, energy companies typically dump it into unlined ponds. The chemical soup—now also contaminated with heavy metals and even radioactive elements—seeps into aquifers and overflows into streams. The severe and irreversible damage associated with fracking includes: Exhaustion of freshwater supplies. Contamination of ground and surface waters. Air pollution from drill and pump rigs. Harms to the health of people (low birth weight, birth defects, increases in congenital heart defects, deformities, allergies, cancer, and respiratory disease) and other living things. Unregulated emissions of methane, which traps 25 times more heat than carbon dioxide. Earthquakes. Effects on subsistence activities, such as agriculture. For and Against Fracking Given these risks, France, Bulgaria, Ireland, and New York State have turned their backs on fracking, banning it or declaring a moratorium in their territories. In Latin America, however, many countries are opening their doors to fracking. Governments are doing so with little or no understanding of its impacts, and in the absence of an adequate process to inform, consult, or invite the participation of affected communities: Mexico promoted fracking through a landmark energy reform law in 2013. As of 2015, 20 wells have been drilled using this technique. Argentina has the largest number of fracking operations in the region, and the largest reserves of shale gas in America. As of 2014, there were more than 500 fracking wells in Neuquén, Chubut, and Rio Negro[6], including wells in the Auca Mahuida reserve and in Mapuche indigenous territories. In Chile, the state-owned oil company ENAP started fracking on the island of Tierra del Fuego in 2013. More drilling is planned in the coming years. Colombia and Brazil have opened public bidding and signed contracts with oil companies for exploitation of unconventional hydrocarbons through fracking. Bolivia's state-owned oil company signed an agreement in 2013 with its counterpart from Argentina to study the potential of fracking in Bolivia. Better together In October 2014, with the help of AIDA, the Regional Alliance on Fracking was formed to raise awareness, generate public debate, and prevent risks associated with the technique. The alliance seeks to ensure that the rights to life, public health, and a healthy environment are respected in Latin America. The idea for the alliance came from previous regional coordination initiatives promoted by Observatorio Petrolero Sur and the Heinrich Böll Foundation. The alliance currently consists of 33 civil society organizations and academic institutions from seven countries in the region. They are working together to: Identify fracking operations in the region, their impacts and affected communities, and promote civil society strategies to stop them. Organize workshops and virtual seminars on the impacts of fracking. Develop international advocacy strategies to stop fracking in the region. Conduct a regional outreach campaign on the issue. The alliance is strengthened by the expertise of its members, its regional scope, and the institutional support provided by organizations in each country. Given its collaborative nature, it is always open to the participation of new institutions and individuals interested in the subject. Major achievements Many civil society organizations, indigenous peoples, and institutions in the region have been working to stop fracking. They have developed strategies to generate information, raise awareness, promote public debate, and influence decision makers. Their achievements encourage us to improve coordination for greater impact throughout Latin America. Already, their efforts have resulted in: More than 30 municipal orders declaring a ban or moratorium on fracking in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Many have been based on the precautionary principle, as well as on concerns about surface and ground waters and public health. Judgments suspending contracts for fracking in Brazilian oil basins in Sao Paulo, Piauí, Bahia, and Paraná. Judges have also ordered Brazil’s National Petroleum Agency not to open further bidding until the environmental risks and impacts of fracking are sufficiently understood. Publications on the impacts of fracking, community awareness campaigns, and a bill – supported by more than 60 national deputies and nearly 20,000 people – to ban fracking in Mexico. Greater public awareness of fracking, and public debate, in Colombia and Bolivia. Through regional collaboration, AIDA will continue to make progress on preventing the impacts of fracking in our communities, and promote an energy future that is both renewable and humane.

Read more