Project

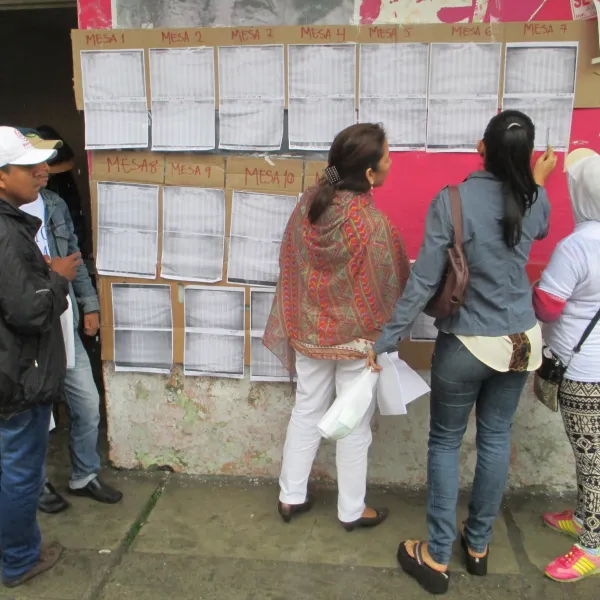

Photo: Andrés Ángel / AIDASupporting Cajamarca’s fight to defend its territory from mining

Cajamarca is a town in the mountains of central Colombia, often referred to as "Colombia’s pantry” due to its great agricultural production. In addition to fertile lands, fed by rivers and 161 freshwater springs, the municipality features panoramic views of gorges and cloud forests. The main economic activities of its population—agriculture and tourism—depend on the health of these natural environments.

The fertile lands of Cajamarca are also rich in minerals, for which AngloGold Ashanti has descended on the region. The international mining conglomerate seeks to develop one of the world’s largest open-pit gold mines in the area. Open-pit mining is particularly damaging to the environment as extracting the metal involves razing green areas and generating huge amounts of potentially toxic waste

The project, appropriately named La Colosa, would be the second largest of its kind in Latin America and the first open-pit gold mine in Colombia. The toxic elements that an operation of that magnitude would leave behind could contaminate the soil, air, rivers and groundwater.

In addition, storms, earthquakes, or simple design errors could easily cause the dams storing the toxic mining waste to rupture. The collapse of similar tailings dams in Peru and Brazil in recent years has caused catastrophic social and environmental consequences.

On March 26, 2017, in a popular referendum, 98 percent of the voters of Cajamarca said “No” to mining in their territory, effectively rejecting the La Colosa project. AIDA is proud to have contributed to that initiative. But even with this promising citizen-led victory, much work remains.

Related projects

Why is lithium mining in Andean salt flats also called water mining?

By Víctor Quintanilla, David Cañas and Javier Oviedo* According to official figures, approximately 2.2 billion people worldwide lack access to drinking water.Despite this panorama, threats to this common good from overexploitation and pollution are increasing. One such threat is the accelerated extraction of lithium in Latin American countries, driven by corporate and state actors to meet the energy transition needs of the global North.Lithium extraction involves enormous water consumption and loss and is essentially water mining.On the continent, the advance of the lithium industry particularly threatens the salt flats and other Andean wetlands of the Gran Atacama region—located in the ecological region of the Puna, on the border of Argentina, Bolivia and Chile—where more than 53 percent of the mineral’s resources (potentially exploitable material) are located.Lithium mining exacerbates the natural water deficit in the area, threatening not only the salt flats, but also the many forms of life that live there. Where does the water used in lithium mining come from?First, it’s necessary to point out that salt flats are aquatic ecosystems located at the bottom of endorheic or closed basins. There, rivers do not flow into the sea but into the interior of the territory, so the water forms lakes or lagoons often accompanied by salt flats due to evaporation.In the salt flats, freshwater and saltwater usually coexist in a delicate balance that allows life to survive.The regions with salt flats, such as the Gran Atacama, are arid or semi-arid, with high evaporation and low rainfall. There we find freshwater aquifers at the foot of the mountains and brine aquifers in the center of the salt flats, both connected and in equilibrium.Brine is basically water with a high salt content, although the lithium mining industry considers it a mineral to justify its exploitation and minimize the water footprint of its activities.In addition to being essential for life, the waters of the salt flats are a heritage resource because they are very old—up to tens of thousands of years—and have been the livelihood of the indigenous people who have inhabited the Puna for thousands of years.When the mining industry moves into a salt flat, it threatens the natural balance and directly affects the relationship between water and the social environment, as well as the relationship between water and other forms of life.To extract lithium from a salt flat, the traditional procedure is to drill the salt flat, pour the brine into large ponds, wait for the water to evaporate so that the lithium concentration increases, send the lithium concentrate to an industrial plant and subject it to chemical treatment to separate the lithium from other salts and finally obtain lithium carbonate or hydroxide: a raw material used mainly in the manufacture of batteries.The continuous and large-scale extraction of brine from saline aquifers alters the natural balance of groundwater. As a result, areas that were previously filled with brine are emptied, causing freshwater from nearby aquifers to move in and occupy those spaces, becoming salinized in the process.The final processes to extract lithium carbonate and separate it from the rest of the compound also require water, which is drawn from surface or underground sources that also supply local communities.Therefore, the water used in lithium mining comes from:Underground freshwater and brine aquifers.Surface sources such as rivers and vegas (land where water accumulates). Therefore, the inherent risk of lithium mining is the overexploitation of these water sources. How much water does lithium mining use?The extraction of lithium by the methods described above involves an enormous consumption and loss of water, which is not returned to the environment because it completely used up, because its properties change, or because it is simply lost through evaporation.According to scientific data, the average water overconsumption in lithium mining is as follows:150 m3 of fresh water used to produce one ton of lithium.350 m3 of brine per ton of lithium.Between 100 and 1000 m3 of water evaporated per ton of lithium produced. To illustrate the loss of water resources in lithium mining, the water lost to evaporation is equivalent to the total water consumption of the population of Antofagasta (166,000 people) for two years. This Chilean city is located 200 km from the Salar de Atacama, where more than 90 percent of the country's lithium reserves are located.In addition to water depletion, lithium mining can also contaminate the resource by producing wastewater containing toxic substances. Our vital relationship with waterUnlike the mining industry, which sees water as just another resource to be exploited, the indigenous communities living in the area have an ancestral connection to the resource on which their economic and productive activities depend, as well as their customs, traditions and worldview.These communities must now confront the pressures on water from the advance of lithium mining, driven by outside interests.But they are doing so with courage, developing processes of defense of water and territory.Let us learn from them to defend a common good without which no way of life is possible.Learn more about the impacts of lithium mining on Andean salt flats in this StoryMap (in Spanish)Watch the recording of the webinar “Evidence of hyperconsumption of water in lithium extraction and production” (in Spanish) *Víctor Quintanilla is AIDA's Content Coordinator; David Cañas and Javier Oviedo are scientific advisors.

Read more

Declaration of a Temporary Reserve Area in the Santurbán Páramo is a victory for the defense of water in Latin America

Civil society organizations celebrate the measure taken by the Colombian Ministry of the Environment, which involves a two year suspension of Canadian company Aris Mining's gold mining project in the páramo.Bogotá, Colombia. The Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) - Mining and Trade Project, MiningWatch Canada, the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) and Common Frontiers Canada celebrate the Colombian Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development’s (MADS) resolution that declares the western side of the Santurbán massif a temporary renewable natural resource reserve area. This major step strengthens the protection of one of the most emblematic high-altitude Andean wetlands, known as páramo, and its related ecosystems, which are fundamental for climate change adaptation and water security in the region for an estimated 2 million people.Resolution 0221, issued on March 3, 2025 by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MADS), delimits and protects an area of 75,344.65 hectares, ensuring a two year provisional suspension of the Soto Norte gold mining project owned by Canadian company Aris Mining and its Colombian subsidiary, Sociedad Minera de Santander S.A.S. (Minesa), which puts Santurbán at risk. Citing the precautionary principle, the resolution prohibits the granting of “new mining concessions, special exploration and exploitation contracts, (...) as well as new environmental permits or licenses for the exploration or exploitation of minerals” in the area until the necessary technical studies are carried out toward its definitive protection. This resolution does not affect agricultural, livestock or tourism activity in the area.However, we are concerned that the resolution leaves in force the concession contract with Calimineros, which has had a subcontract with Minesa to formalize [its small-scale mining activities] since 2020, and from which Minesa promises to buy and process mineralized material. We encourage the competent authorities to suspend evaluation of its environmental license application and extension of the formalization subcontract, due to potential environmental impacts on Santurbán and because it is effectively part of the Soto Norte project.The páramo and related ecosystems are highly sensitive, recognized for their role in water regulation, carbon capture, and the conservation of endemic biodiversity. The removal of vegetation cover and the fragmentation of ecosystems that mining in Santurbán would generate could affect the ecological balance, biodiversity, and the provision of ecosystem services essential for life; acidify and reduce the amount of available fresh-water; and break the ecological interconnectivity with other biomes and ecosystems, destroying their capacity to sequester carbon and causing irreparable damage.For these reasons, we appreciate that the resolution seeks to prevent mining development in this highly sensitive and environmentally important area, preventing degradation of the watersheds that arise from Santurbán and preserving the water cycle.Sebastián Abad-Jara, an attorney for AIDA, pointed out that "by protecting Santurbán, Colombia ratifies its commitment to meet global environmental goals in terms of biodiversity, climate and wetlands, and sets a high bar for the governments of other countries where these ecosystems are similarly threatened by mining activity, such as Peru and Ecuador.""We celebrate this declaration as an important first step toward the consolidation of the western side of the Santurbán massif as a permanent reserve area, definitively protecting this important water source, vital for all who depend on it," said Jen Moore, associate fellow at IPS - Mining and Trade Project.Viviana Herrera, Latin America Program Coordinator for MiningWatch Canada, added that "this resolution is the result of the Committee for the Defence of Water and Páramo of Santurbán’s hard work, which has faced harassment and intimidation for its work in defense of the páramo, as well as disinformation campaigns about the supposed harmful effects of the resolution on agricultural activity."AIDA, IPS-Mining and Trade Project, MiningWatch Canada, CIEL and Common Frontiers Canada support the adoption of this protection measure for Santurbán. We also encourage the national and local government to carry out the necessary technical studies for its definitive protection, and to take preventive measures to avoid the cumulative environmental impacts of mining in the area given other projects that already have mining licenses. Furthermore, we reiterate the urgency of adopting measures to protect environment defenders in Colombia who stand up for the páramo.The Santurbán experience provides valuable lessons and should serve as an example to promote legislation for environmental protection in Latin America that focuses on the human right to water and the balance and integrity of fragile ecosystems, such as the páramo and other high-altitude ecosystems.#OurGoldIsWater Press contactsVictor Quintanilla (Mexico), AIDA, [email protected], +5215570522107Jennifer Moore, IPS, [email protected], +12027049011 (prensa IPS)Viviana Herrera, Mining Watch Canada, [email protected], +14389931264Alexandra Colón-Amil, CIEL, [email protected], +12024550253

Read more

Learn about the negotiations to reduce maritime shipping emissions

The decarbonization of productive and economic activities is essential and urgent to address the triple crisis –climate, pollution and biodiversity loss– that the world is facing.In maritime shipping –which moves 10 billion tons of cargo each year and accounts for 2.9% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including carbon dioxide (CO2)– the global need to reduce and eventually eliminate these emissions is being addressed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the UN specialized agency responsible for setting standards for safe, efficient and environmentally sound shipping.The move toward decarbonization is critical because without significant change, shipping emissions could increase by as much as 50% by 2050.The IMO has a revised emissions reduction strategy that was agreed in 2023 by the 175 countries that make up the organization. It is expected to reduce emissions from the sector by up to 30% by 2030, 80% by 2040 and reach net zero by around 2050. Implementation of the strategy is currently the subject of international negotiations.AIDA is participating in these negotiations as part of the Clean Shipping Coalition, an international coalition of organizations. In addition, AIDA is coordinating efforts with Ocean Conservancy and Fundación Cethus to generate advocacy with Latin American countries and to collaborate with updated technical information on the progress of the negotiations and their implications for the region.The decarbonization of global shipping and its economic impact is a very important discussion for Latin America and the Caribbean. It is necessary that all countries and economic sectors align themselves with clear targets and that all impacts are assessed equally and fairly, as well as the ways in which countries can mitigate them. Read on to learn more about this important process. What measures are being discussed to reduce emissions from maritime shipping?Negotiations are underway at the international level to select the package of measures needed to meet the 2023 targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from shipping. This package will include both technical and economic measures. Its final structure will be decided in April this year at the IMO headquarters in London, marking a global milestone in the fight against the climate crisis.Technical measures include a global fuel standard, carbon capture on ships, energy efficiency measures for the fuels used, and reductions in ship speed. They all aim to make maritime transport as efficient as possible in terms of the fuels used and to gradually phase out the use of the most polluting fuels. This means using the least amount of energy, emitting the least amount of carbon dioxide and keeping the sector in operation.In addition to technical measures, economic measures are proposed to put a price on carbon emissions from maritime transport. Increasing the efficiency of ships is expected to have not only a technological component but also a market incentive. This combination is crucial for achieving emission reduction targets, as it will provide both the public and private sectors with the necessary resources:The economic resources to invest in the new technologies, new fuels, and other investments needed for the energy transition.An economic stimulus to close the current cost gap between fossil fuels and near-zero emission clean technologies. To define a price for carbon dioxide emissions, there are two main proposals:The first has a flexible structure with respect to emissions. In its simplest form, it takes account of differences in emissions when implementing the measure. To this end, a "permissible limit" of carbon dioxide emissions is envisaged, with ships being divided into those below and those above the limit. The former could receive a financial reward, and the latter would pay a fee for the carbon dioxide emitted under a system of emission quotas. In this sense, although there is a mechanism to regulate emissions below the set limit, the tolerance of these limits offers the possibility of an accelerated reduction, which could delay the energy transition that the climate crisis requires.The second has a universal structure, i.e. a fixed price for all CO2 emissions generated by the operation of the maritime fleet. The aim is to create a market stimulus that will increase the demand for new low-emission technologies (new ships and fuels) and encourage maritime operators to purchase them in order to avoid paying a fee. This measure is expected to provide more accurate monitoring of total emissions from ships, motivate a faster and more pronounced energy transition, and collect and then redistribute a significant number of economic resources among maritime operators and countries to mitigate the disproportionate costs and negative impacts of the decarbonization process. What does decarbonizing shipping mean for Latin America and the Caribbean?According to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), Latin America and the Caribbean is one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change-related disasters, so actions aimed at achieving decarbonization targets in different sectors of the regional economy are essential to address the climate crisis.On the other hand, actions specifically aimed at decarbonizing maritime transport will have different impacts in the short, medium and long term in each of the countries of the continent. For example, the choice of one or the other proposal for the payment of a tariff for the sector's CO2 emissions - the flexible modality or the fixed price - will have a different impact in each country. What all scenarios have in common is that the region will be strongly affected by the process of decarbonizing maritime transport.In this context, it is important for countries to identify the scenarios that allow them a greater range of actions to compensate for these impacts and to ensure that the transition is equitable and fair, without leaving any country behind.In economic terms, the introduction of a universal price on CO2 emissions would allow States to receive part of the economic resources generated to compensate and mitigate the effects of decarbonization. The amounts and forms of this transfer of resources will be agreed within the IMO. The combination of more ambitious measures (technical and economic) is expected to raise up to $120 billion annually in the coming years. The flexible proposal for paying for emissions does not include mechanisms for redistributing resources, as these would go directly to ship operators and fuel producers. This would leave countries to mitigate the impact of decarbonization with their own resources.From an environmental perspective, without the incentive of a universal price, there is a risk that the flexible scheme will indirectly encourage the continued use of fuels that generate CO2 emissions, particularly in regions with limited economic resources to invest in the least polluting state-of-the-art technology. This would result in a delay in achieving emission reduction targets for the world's shipping fleet and would move countries away from meeting their climate change commitments under the IMO.In general, the costs of reducing CO2 emissions from shipping and other sectors, which are at the root of the current climate crisis, are a reality for all countries, although the impact varies by region. The active participation of Latin America and the Caribbean in the international discussions on this issue throughout 2025 is essential to ensure that the energy transition and the reduction of maritime emissions are fair and equitable. It is important that the countries of the continent adopt a position that allows them to protect their economic and environmental interests from the economic consequences of this process. If the IMO's decarbonization strategy does not live up to its ambitions, we will have a shipping industry that exacerbates the climate crisis and its impacts. The success of this strategy will be the achievement of a global consensus on environmental considerations. The equity and fairness of the transition must be one of the key elements. Recognizing the differentiated impacts of maritime decarbonization measures and their compensation, especially in the most affected countries, will ensure a triumph based on criteria of justice and environmental equity.

Read more