Project

Luchando por justicia para víctimas de contaminación tóxica en La Oroya, Perú

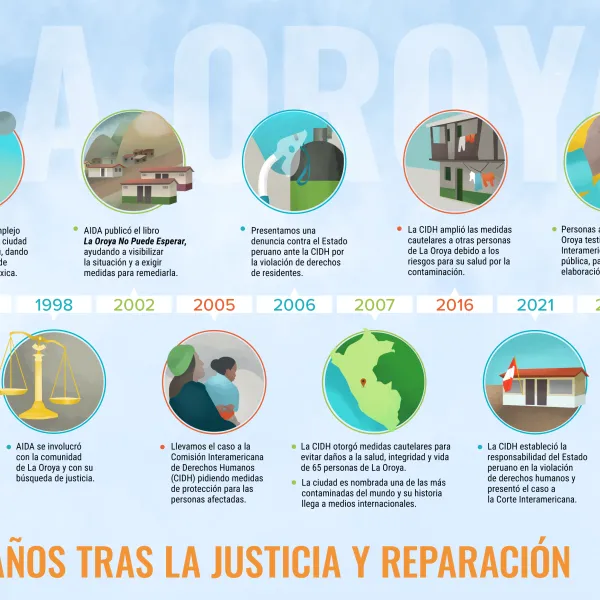

Por más de 20 años, residentes de La Oroya buscan justicia y reparación por la violación de sus derechos fundamentales a causa de la contaminación con metales pesados de un complejo metalúrgico y de la falta de medidas adecuadas por parte del Estado.

El 22 de marzo de 2024, la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos dio a conocer su fallo en el caso. Estableció la responsabilidad del Estado de Perú y le ordenó adoptar medidas de reparación integral. Esta decisión es una oportunidad histórica para restablecer los derechos de las víctimas, además de ser un precedente clave para la protección del derecho a un ambiente sano en América Latina y para la supervisión adecuada de las actividades empresariales por parte de los Estados.

Antecedentes

La Oroya es una ciudad ubicada en la cordillera central de Perú, en el departamento de Junín, a 176 km de Lima. Tiene una población aproximada de 30.533 habitantes.

Allí, en 1922, la empresa estadounidense Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation instaló el Complejo Metalúrgico de La Oroya para procesar concentrados de minerales con altos niveles de plomo, cobre, zinc, plata y oro, así como otros contaminantes como azufre, cadmio y arsénico.

El complejo fue nacionalizado en 1974 y operado por el Estado hasta 1997, cuando fue adquirido por la compañía estadounidense Doe Run Company a través de su filial Doe Run Perú. En 2009, debido a la crisis financiera de la empresa, las operaciones del complejo se suspendieron.

Décadas de daños a la salud pública

El Estado peruano —debido a la falta de sistemas adecuados de control, supervisión constante, imposición de sanciones y adopción de acciones inmediatas— ha permitido que el complejo metalúrgico genere durante décadas niveles de contaminación muy altos que han afectado gravemente la salud de residentes de La Oroya por generaciones.

Quienes viven en La Oroya tienen un mayor riesgo o propensión a desarrollar cáncer por la exposición histórica a metales pesados. Si bien los efectos de la contaminación tóxica en la salud no son inmediatamente perceptibles, pueden ser irreversibles o se evidencian a largo plazo, afectando a la población en diversos niveles. Además, los impactos han sido diferenciados —e incluso más graves— entre niños y niñas, mujeres y personas adultas mayores.

La mayoría de las personas afectadas presentó niveles de plomo superiores a los recomendados por la Organización Mundial de la Salud y, en algunos casos, niveles superiores de arsénico y cadmio; además de estrés, ansiedad, afectaciones en la piel, problemas gástricos, dolores de cabeza crónicos y problemas respiratorios o cardíacos, entre otros.

La búsqueda de justicia

Con el tiempo, se presentaron varias acciones a nivel nacional e internacional para lograr la fiscalización del complejo metalúrgico y de sus impactos, así como para obtener reparación ante la violación de los derechos de las personas afectadas.

AIDA se involucró con La Oroya en 1997 y desde entonces hemos empleado diversas estrategias para proteger la salud pública, el ambiente y los derechos de sus habitantes.

En 2002, nuestra publicación La Oroya No Puede Esperar ayudó a poner en marcha una campaña internacional de largo alcance para visibilizar la situación de La Oroya y exigir medidas para remediarla.

Ese mismo año, un grupo de pobladores de La Oroya presentó una acción de cumplimiento contra el Ministerio de Salud y la Dirección General de Salud Ambiental para la protección de sus derechos y los del resto de la población.

En 2006, obtuvieron una decisión parcialmente favorable del Tribunal Constitucional que ordenó medidas de protección. Pero, tras más de 14 años, no se tomaron medidas para implementar el fallo y el máximo tribunal no impulsó acciones para su cumplimiento.

Ante la falta de respuestas efectivas en el ámbito nacional, AIDA —junto con una coalición internacional de organizaciones— llevó el caso ante la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (CIDH) y en noviembre de 2005 solicitó medidas cautelares para proteger el derecho a la vida, la integridad personal y la salud de las personas afectadas. Luego, en 2006, presentamos una denuncia ante la CIDH contra el Estado peruano por la violación de los derechos humanos de residentes de La Oroya.

En 2007, como respuesta a la petición, la CIDH otorgó medidas de protección a 65 personas de La Oroya y en 2016 las amplió a otras 15 personas.

Situación actual

Al día de hoy, las medidas de protección otorgadas por la CIDH siguen vigentes. Si bien el Estado ha emitido algunas decisiones para controlar de algún modo a la empresa y los niveles de contaminación en la zona, estas no han sido efectivas para proteger los derechos de la población ni para implementar con urgencia las acciones necesarias en La Oroya.

Esto se refleja en la falta de resultados concretos respecto de la contaminación. Desde la suspensión de operaciones del complejo en 2009, los niveles de plomo, cadmio, arsénico y dióxido de azufre no han bajado a niveles adecuados. Y la situación de las personas afectadas tampoco ha mejorado en los últimos 13 años. Hace falta un estudio epidemiológico y de sangre en los niños y las niñas de La Oroya que muestre el estado actual de la contaminación de la población y su comparación con los estudios iniciales realizados entre 1999 y 2005.

En cuanto a la denuncia internacional, en octubre de 2021 —15 años después de iniciado el proceso—, la CIDH adoptó una decisión de fondo en el caso y lo presentó ante la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos tras establecer la responsabilidad internacional del Estado peruano en la violación de derechos humanos de residentes de La Oroya.

La Corte escuchó el caso en una audiencia pública en octubre de 2022. Más de un año después, el 22 de marzo de 2024, el tribunal internacional dio a conocer la sentencia del caso. En su fallo, el primero en su tipo, responsabiliza al Estado peruano por violar los derechos humanos de residentes de La Oroya y le ordena la adopción de medidas de reparación integral que incluyen remediación ambiental, reducción y mitigación de emisiones contaminantes, monitoreo de la calidad del aire, atención médica gratuita y especializada, indemnizaciones y un plan de reubicación para las personas afectadas.

Conoce los aportes jurídicos de la sentencia de la Corte Interamericana en el caso de La Oroya

Partners:

Proyectos relacionados

Evidenciando el impacto del desarrollo en los derechos humanos y el ambiente

"There we were men and women, children, elders and leaders-who dared to refuse burning or destruction of the huts on the banks of the river, theft and loss of goods, abuse, insults and humiliation by the police, military and public companies Medellin forcibly vacated the beaches to make way for development. " With those words, Isabel Cristina Zuleta, leader of the Movement Living Rivers and victims of forced displacement because of the hydroelectric project Hidroituango in Colombia, testified to the situation that she, community members and thousands of Colombians affected by such projects go through a long time. He did so in a hearing before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH) last month. Astrid Puentes, AIDA Executive Co-Director, attended the hearing along with Living Rivers, Tierra Digna, Asoquimbo, the Inter-Church Justice and Peace Commission, the Judicial Freedom and several colleagues from Colombia organizations. She argued before the Commission that in Colombia forced because of projects 'development' as dams and mines displacement is not recognized as a violation of human rights by the state, which makes the people affected are unprotected. At the hearing Bridges outlined the three main causes of forced displacement by projects: the close relationship between armed conflict and the implementation of megaprojects, flexibility and violation of rules in its approval and implementation, and direct impacts their performance. It also asked the Commission to urge the Colombian government to guarantee the rights of victims, repair damage and take appropriate measures to prevent such displacement measures. Bridges described human rights violations arising from the implementation of specific projects like the dam El Quimbo in the department of Huila and situations like those experienced in the mining district of La Jagua de Ibirico, department of Cesar, where entire communities have been displaced due to air pollution caused by coal projects. Inadequate implementation of projects of "development" in Colombia and the region also violates Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ESCR), especially the right to a healthy environment. In this regard, AIDA and organizations in the region participated in a hearing convened ex officio by the Commission to analyze the situation of ESC rights in the continent. In it, Maria Jose Veramendi Villa, senior lawyer AIDA, said the main cause of the violation of the right to a healthy environment is the failure of States to their environmental obligations and human rights by implementing mining and energy projects and infrastructure, among others. The problem has worsened in recent years. "The Commission has found different manifestations of the problem through at least 40 thematic hearings that have taken place in the past decade, and have illustrated the serious territorial, cultural and environmental conflicts generated by the violation of ESCR "Veramendi Villa recalled during the hearing. We need a Commission with a firm and resolute against the implementation of policies and projects that violate human rights, and thus bring justice to those who do not find in their countries position.

Leer másBuscando compromisos y soluciones sostenibles en la COP20

La reunión mundial más importante sobre cambio climático esta cada vez más cerca. Las expectativas son altas. La Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre Cambio Climático (COP20) en Lima, Perú, debe concluir con un borrador del nuevo acuerdo climático que será suscrito en 2015. La conferencia ofrece además una oportunidad clave para que los países mantengan los compromisos financieros adquiridos en conferencias previas. AIDA participará de la conferencia bajo dos objetivos principales. El primero es defender el financiamiento pleno del Fondo Verde del Clima. El segundo es participar en la conversación para asegurar que el nuevo acuerdo climático tome en cuenta el impacto del cambio climático en los derechos humanos. La Convención Marco de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático estableció el Fondo Verde del Clima para financiar programas y proyectos para la adaptación y mitigación del cambio climático. Los países más vulnerables al cambio climático tendrán prioridad en las inversiones. “Buscamos que se hagan compromisos concretos, tener claridad sobre la ruta que seguirán los países desarrollados para que la lucha contra el cambio climático tenga un apoyo financiero sostenible en el tiempo”, afirma Andrea Rodríguez, abogada sénior de AIDA. Hasta la fecha, el Fondo Verde del Clima ha recibido 9.6 mil millones de dólares en promesas de contribuciones. Nuestro objetivo en la conferencia de Lima es generar compromisos adicionales que eleven esa cifra a por lo menos 15 mil millones. También vamos a trabajar con los gobiernos para asegurar que cumplan con su compromiso de contribuir con 100 mil millones de dólares por año a partir del 2020 para garantizar así recursos predecibles y sostenibles. AIDA trabajará con redes globales como Climate Action Network International (CAN-I) para supervisar estas contribuciones financieras. AIDA, junto con organizaciones socias, está organizando el Día de Financiamiento Climático de América Latina y el Caribe el sábado 6 de diciembre. El evento reunirá a actores de persos sectores para facilitar el diálogo y la construcción de capacidades sobre aspectos clave de financiamiento climático que afectan a la región. Una de las sesiones abordará el rol del Fondo Verde del Clima en la contribución a un cambio transformador en América Latina. “Aprovechando el contexto de negociaciones climáticas, les recordaremos a los tomadores de decisiones que las medidas para mitigar el cambio climático deben ser realmente sostenibles y eficientes”, afirmó Rodríguez. “Los esfuerzos de mitigación no deben promover proyectos como las grandes represas, consideradas fuente de energía limpia a pesar de que emiten grandes cantidades de metano, especialmente en zonas tropicales.” La conferencia brindará una oportunidad para que AIDA trabaje con los negociadores para garantizar que consideraciones de derechos humanos, las cuales fueron reconocidas en acuerdos climáticos previos, formen parte del siguiente acuerdo. De forma paralela a la COP20, participaremos la Cumbre de los Pueblos, un importante encuentro alternativo de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil. En él AIDA compartirá su experiencia sobre la fracturación hidráulica o fracking y sus implicaciones para el ambiente en América Latina y para el clima global. Ta mantendremos al tanto a lo largo de la conferencia en nuestro sitio web, Facebook y Twitter. ¡No dejes de seguirnos! #RumboCOP20

Leer más

México ante la oportunidad de proteger mejor su ambiente

Sandra Moguel, abogada de AIDA, @sandra_moguel La pirinola es una pieza de material duro que tiene seis caras planas en las que lleva distintas leyendas. En varios países de América Latina es utilizada para jugar y hacer apuestas. Tras hacerla girar, la pirinola se detiene en uno de sus contornos y le muestra al jugador lo que debe hacer con cierta cantidad de fichas: PON 1, PON 2, TOMA 1, TOMA 2, TOMA TODO y TODOS PONEN. México atraviesa momentos de desaliento colectivo en los que todo tiene color de fatalidad. Pero no todo está perdido. En términos de la protección de su ambiente, el país aún tiene la oportunidad de decidir acertadamente la suerte de su patrimonio natural y de apostar por un desarrollo sostenible. TODOS PONEN: La historia incómoda de Paraíso del Mar Paraíso del Mar es un proyecto turístico ubicado en la barra arenosa conocida como El Mogote, en la Bahía de La Paz, Baja California Sur. El proyecto propone la construcción de un mega resort con 2,050 cuartos de hotel y 4,000 viviendas, campos de golf y una marina. A principios de 2013, un tribunal mexicano declaró ilegal y de forma definitiva el permiso ambiental que la Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT) había otorgado al proyecto. El argumento de la decisión fue que la SEMARNAT no aplicó su legislación ambiental al evaluar el impacto ambiental de Paraíso del Mar. Sin embargo, algunas obras del proyecto ya habían sido construidas. Como consecuencia, el manglar de la zona ha desaparecido casi en su totalidad, y el paisaje y la línea costera ya han sido modificados. Con una autorización de impacto ambiental ilegal e irresponsable todos pierden: ¿Quién indemniza a los empresarios que invierten en la construcción del proyecto?, ¿quién repara el daño? o ¿quién restaura la vista del paisaje? La sociedad en su conjunto se ve afectada. Basta recordar los destrozos que ocasionó el huracán Odile en Los Cabos. Los aspectos de cambio climático y fenómenos meteorológicos debieron tomarse en cuenta al evaluar los proyectos turísticos construidos en esa zona, algo que no ocurrió. La evaluación de impacto ambiental es la revisión de los efectos causados por las actividades humanas en el medio ambiente. El objetivo de este instrumento es identificar si las afectaciones a los ecosistemas pueden ser mitigadas o compensadas. Desafortunadamente, las leyes que regulan la manera en que la autoridad ambiental realiza esa tarea, parecen simuladas y la evaluación se convierte en un mero trámite que perjudica a la biodiversidad y a la sociedad. TOMA 1: Contribuyendo a una solución La Asociación Interamericana para la Defensa del Ambiente (AIDA) y su socio Earthjustice, en representación de organizaciones de la sociedad civil, presentaron una petición ciudadana a la Comisión para la Cooperación Ambiental (CCA) —organismo internacional creado en el marco del Acuerdo de Cooperación Ambiental de América del Norte, celebrado entre México, Estados Unidos y Canadá— solicitando una investigación sobre la autorización de Paraíso del Mar y otros proyectos similares en el Golfo de California. En la petición se afirma que el Gobierno mexicano no aplicó su legislación ambiental al evaluar el impacto ambiental de los proyectos en humedales costeros del Golfo. El Secretariado de la CCA tuvo el mismo criterio y recomendó elaborar un Expediente de Hechos (investigación pormenorizada). PONEN DOS: La decisión depende de al menos dos gobiernos En los próximos días, al menos dos de los tres Ministros del Medio Ambiente de Estados Unidos, Canadá y México deberán votar a favor de llevar adelante la mencionada investigación. Esta votación es una oportunidad para promover la transparencia y la participación de la sociedad en asuntos ambientales. Es la ocasión perfecta para que el Gobierno de México genere la credibilidad, la confianza y los espacios de diálogo que el país está pidiendo a gritos. Un Expediente de Hechos no contiene una calificación sobre los argumentos de los peticionarios. Tampoco contiene recomendaciones de la CCA para resolver el problema. Se trata más bien de un examen detallado que es fuente de retroalimentación para la misma SEMARNAT sobre las preocupaciones de la sociedad civil. Llama la atención que de las 41 peticiones ciudadanas que se han presentado en contra de México ante la CCA, 19 tienen que ver con la evaluación de impacto ambiental. Esto quiere decir que sus ciudadanos cuestionan la discrecionalidad con la que se emplea esa herramienta y con la que se determina un impacto ambiental. TOMAN TODOS: ¿Qué concluimos? Haciendo eco de la reflexión de Paola Zavala, las movilizaciones sociales deben ir acompañadas de una agenda de exigencias puntuales y compartidas entre los miembros sociedad civil. No se trata solo de gritar y desahogarse en las calles. De ahí la importancia de la participación constructiva. En el caso del Golfo de California, los peticionarios, apoyados por organizaciones de la sociedad civil y académicos, exigimos que la SEMARNAT aplique su legislación ambiental aprobando proyectos con base en la descripción de obras completas que contengan la mejor información disponible, que describan la totalidad de los impactos acumulativos y residuales, que no contravengan tratados internacionales ni las normas sobre especies en peligro o en riesgo, y sobre protección de manglares. El Expediente de Hechos no es una panacea, pero si generará una agenda de diálogo y concientización para funcionarios públicos, empresarios y sociedad civil sobre la importancia de la evaluación del impacto ambiental. Será un gran paso en el camino de tomar decisiones que garanticen el desarrollo sostenible en México.

Leer más