Project

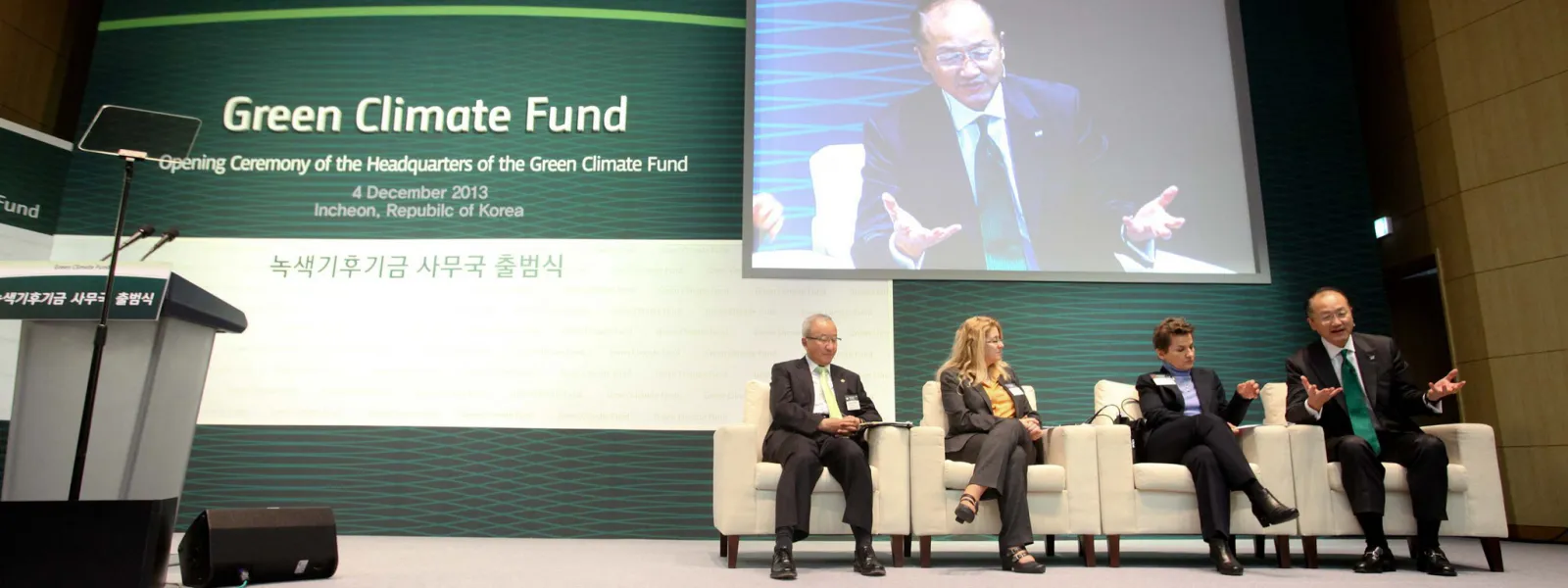

Photo: GCFAdvocating before the Green Climate Fund

The Green Climate Fund is the world's leading multilateral climate finance institution. As such, it has a key role in channelling economic resources from developed to developing nations for projects focused on mitigation and adaptation in the face of the climate crisis.

Created in 2010, within the framework of the United Nations, the fund supports a broad range of projects ranging from renewable energy and low-emissions transportation projects to the relocation of communities affected by rising seas and support to small farmers affected by drought. The assistance it provides is vital so that individuals and communities in Latin America, and other vulnerable regions, can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and address the increasingly devastating impacts of global warming.

Climate finance provided by the Green Climate Fund is critical to ensure the transformation of current economic and energy systems towards the resilient, low-emission systems that the planet urgently needs. To enable a just transition, it’s critical to follow-up on and monitor its operations, ensuring that the Fund effectively fulfills its role and benefits the people and communities most vulnerable to climate change.

Reports

Read our recent report "Leading participatory monitoring processes through a gender justice lens for Green Climate Fund financed projects" here.

Partners:

Related projects

Latest News

Letter: Concerning the Green Climate Fund and large hydropower

The 282 undersigned organizations write to express our significant concern regarding the use of GCF resources to support large hydropower, and, in particular, the following proposals in the GCF’s pipeline: (i) Qairokkum Hydropower Rehabilitation, Tajikistan; (ii) Upper Trishuli-1, Nepal; and (iii) Tina River Hydro Project, Solomon Islands. The GCF can and should help pay for the incremental costs of renewable energy sources, which are often less “bankable” (though less so all the time). However, we wish to highlight that large dams are different from wind, solar and other technologies because they fail to fulfill the GCF Investment Criteria. For example: (i) Impact potential: Dams emit significant amounts of greenhouse gases, particularly methane, and damage carbon sinks; (ii) Paradigm shift potential: Large hydro is a non-innovative technology that has not seen significant technical or financial breakthroughs in decades; (iii) Sustainable development: Dams have high negative co-impacts with regard to the environment, human rights, and economic cost. By interrupting rivers and flooding lands, they irreversibly harm livelihoods and ecosystems. Because they routinely cost double their estimates, large dams stretch government budgets and increase borrowing costs; (iv) Needs of the recipient: Hydropower projects are particularly vulnerable to climate change, and many countries are already alarmingly over-dependent on hydropower (as is the case with Tajikistan and Nepal). GCF should support efforts in these countries to diversify their energy mix, helping them improve their resilience and adaptive capacities; and, (v) Efficiency and effectiveness: Dams all over the world are losing generation capacity because of climate change-induced droughts. In addition, each of the dam-related projects in the GCF’s pipeline suffers significant deficiencies: Qairokkum Hydropower Rehabilitation: This funding proposal is expected at the April board meeting. The board should reject it. The project aims to extend the life of a Soviet-era dam, built in the 1950s. It is not innovative in any way, deepens Tajikistan’s already alarming overdependence on climate-vulnerable hydro, and fails to address critical environmental problems of the original dam, among other concerns. Upper Trishuli-1: Though not up for consideration at the April board meeting, Upper Trishuli has been in the project pipeline for many months and should be expeditiously removed from it. With more than 30 hydro projects either operating, in construction, or planned on the Trishuli River, the project would have no transformational impact. It faces severe climate and disaster risks, would deepen Nepal’s overdependence on climate-vulnerable hydro, and would have significant impacts on indigenous communities and the environment that have not been adequately studied or addressed. There is also no assessment of the project’s vulnerability to earthquakes, despite the area being highly seismic. Tina River Hydro Project: Expected at the April board meeting, this 15 MW project is intended to reduce the Solomon Islands’ reliance on imported diesel. The project does not include an assessment of climate vulnerability, threatens a world-class biodiversity hotspot, and is very costly. Meanwhile, Solomon Islands has considerable renewable energy potential that has not been sufficiently studied. These issues and others are detailed in a letter sent previously to the Board. Thank you for your attention to this most important matter. We look forward to working with you and the Secretariat to ensure that the GCF is a transformational institution of the highest social and environmental caliber. That cannot be accomplished if the GCF finances large hydropower.

Read more

Letter to Green Climate Fund Board and Advisors: Concern regarding the use of GCF resources to support large hydropower

We write to express our concern regarding the use of GCF resources to support large hydropower in general, and in particular the following proposals in the GCF pipeline: Qairokkum Hydropower Rehabilitation, Tajikistan Upper Trishuli-1, Nepal Tina River Hydro Project, Solomon Islands Large hydropower is a non-innovative, last-century technology with dubious climate mitigation benefits and a long track record of exceedingly high financial, environmental, and social costs. Supporting such proposals would not be consistent with the Fund’s goal, to promote a paradigm shift toward lowemission, climate resilient development, in the context of sustainable development. Further, large hydropower projects would not meet the GCF’s selection criteria related to impact, paradigm shift potential, sustainable development, and efficiency and effectiveness. The reasons why the GCF should not support large hydropower are described in the annex, and briefly summarized here: Large dams are vulnerable to climate change: more frequent droughts make them inefficient and increased rainfall reduces their lifespan. Large dams exacerbate climate change: considerable amounts of greenhouse gasses, notably methane (30 times more potent than CO2), are emitted from reservoirs; and their construction damages carbon sinks, including forests and rivers. Large dams harm biodiversity, which in turn impairs communities’ capacity to adapt to a changing climate. Large dams can negatively affect local communities by impoverishing them, breaking social networks, and negatively affecting livelihoods and cultures. Large dams can become dangerous: climate change-related extreme weather events and earthquakes can cause dams to fail, jeopardizing lives and property downstream. Large dams are not economical and are ill suited to address urgent energy needs: recent studies clearly demonstrate that large dams typically suffer significant cost and time overruns. Better energy options are widely available and the GCF should play a fundamental role in promoting them.

Read more

The role of civil society in the Green Climate Fund

Climate change is real, and its impacts are here to stay. The nations of the world have agreed that, to get out of this mess, they must act together. But beyond setting intentions, little progress has been made. One important opportunity to get things done is the Green Climate Fund, the primary financial mechanism of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It’s a relatively new institution with the ability to move large quantities of money from rich countries to those in development. With these resources, the most vulnerable and least financially equipped nations can develop the projects and programs they need to confront climate change. How the Fund works in practice The Fund is a complex mechanism in which diverse actors interact. The Board of Directors, in charge of governing and supervising the Fund, is made up of 24 members, 12 representatives from developed nations and 12 from developing ones. The Independent Secretariat implements the decisions adopted by the Board. The Fund relates to countries through the National Designated Authorities or Focal Points, which are entities designated within each nation. The Fund also accredits national, regional and international institutions to channel economic resources through the presentation and implementation of climate proposals. These are called Accredited Entities. Last, but certainly not least, observers from civil society and the private sector play a key role in ensuring that the Fund takes into account the needs of local populations, especially the most vulnerable, when approving projects and programs to combat climate change. How decisions get made In practice, the Fund has been built at meetings of its Board of Directors, held every three months. There, board members discuss and decide on the policies that shape the Fund. They also grant accreditation to entities that will channel funds from the GCF to the different countries, and approve the projects and programs that the Fund will finance. Last October, I was fortunate to participate, as a civil society observer, at the 14th meeting of the Board, which was held at the Fund’s headquarters in Songdo, South Korea. I had the opportunity to see, on the ground, how this complex international mechanism works and, above all, how civil society contributes. It quickly became clear to me that the working conditions of civil society are not easy. To begin with, there is no economic support for civil society representatives that must travel and stay abroad at least three times a year to attend the board meetings. Inside the meetings of the Board, only “active observers” can participate: two from civil society and two from the private sector. The remaining observers sit in an adjoining room, following the meeting on television screens. Civil society has the right to speak, but this right can only be exercised by the two active observers, and only if the Co-Chairmen of the Board of Directors approve. All civil society interventions are previously discussed, prepared and perfected by the coalition of observers. This leads to many sleepless nights, since the subjects are broad and complex. In practice, civil society contributions are relegated to the end of the Board’s discussions. When time is scarce, a common reality, many times the right to speak is denied. This can be extremely frustrating, since crucial contributions are lost. Why civil society support is important Civil society contributes to the construction of the Fund’s policies with the objective of elevating its standards. Among other tasks, each funding proposal is studied, and the communities potentially affected by or benefitting from it are contacted, in order to understand what the project or program may actually involve, beyond what appears on paper. That’s why the informal work that civil society does “behind the scenes” is so important. It is the work done during recess, at lunchtime, and in the corridors. Gradually, civil society observers build relationships with decision makers (Board members and advisors) and are able to share their ideas, concerns and suggestions with them. The results of civil society’s work are being seen in decision-making, slowly but surely. The Green Climate Fund offers hope because its guidelines are correctly posed: it seeks to promote transformation and paradigmatic change, promises transparency, and its decisions are made giving equal weight to representatives of developed and developing nations. Its mandate is to promote “country ownership” of the programs and projects it finances, that is, to ensure they are guided by the needs and priorities of the beneficiary countries. In addition, the Fund has an obligation to act with a gender approach. However, the Fund also has problems and shortcomings. That’s why involvement of civil society is critical. Because they do not represent any government, political party or other interest, civil society observers ensure the protection of the environment, respect for human rights, and the participation and inclusion of people directly affected by climate change. The physical participation of civil society in Board meetings is vital. They ensure the Fund takes into account the voices of the communities directly affected by or benefitting from the financing. Learn more about the Fund on our website!

Read more