Project

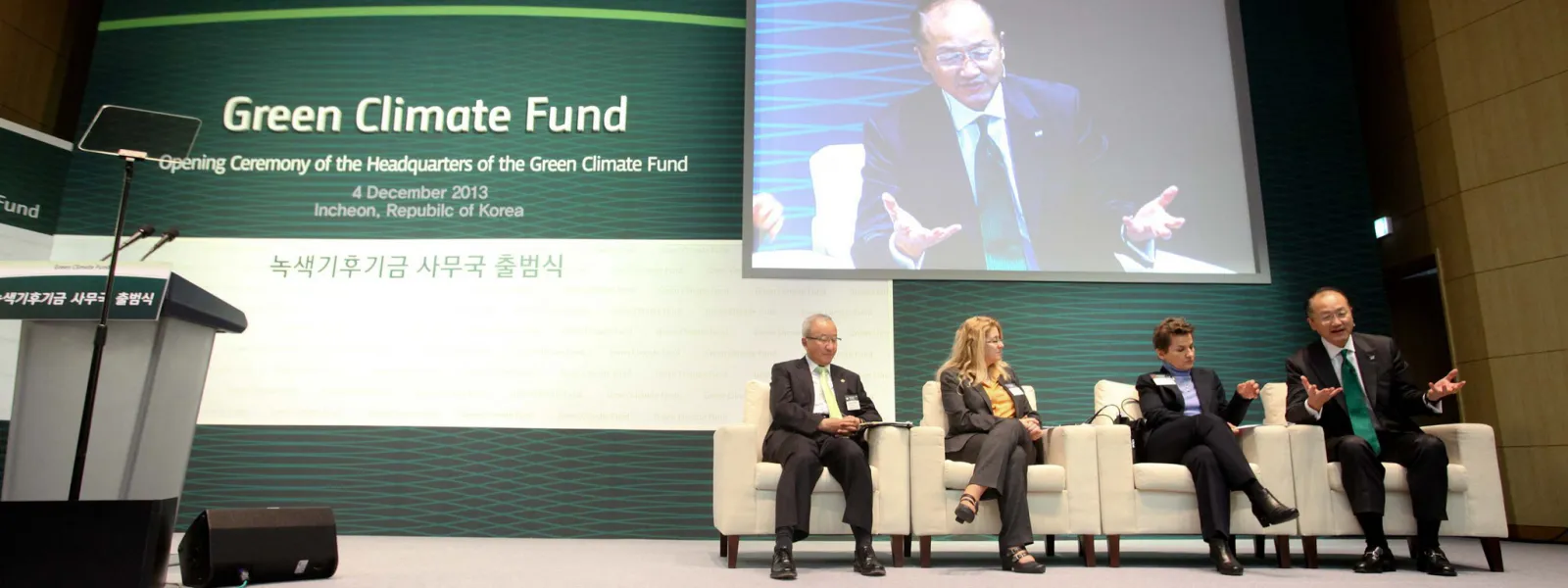

Photo: GCFAdvocating before the Green Climate Fund

The Green Climate Fund is the world's leading multilateral climate finance institution. As such, it has a key role in channelling economic resources from developed to developing nations for projects focused on mitigation and adaptation in the face of the climate crisis.

Created in 2010, within the framework of the United Nations, the fund supports a broad range of projects ranging from renewable energy and low-emissions transportation projects to the relocation of communities affected by rising seas and support to small farmers affected by drought. The assistance it provides is vital so that individuals and communities in Latin America, and other vulnerable regions, can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and address the increasingly devastating impacts of global warming.

Climate finance provided by the Green Climate Fund is critical to ensure the transformation of current economic and energy systems towards the resilient, low-emission systems that the planet urgently needs. To enable a just transition, it’s critical to follow-up on and monitor its operations, ensuring that the Fund effectively fulfills its role and benefits the people and communities most vulnerable to climate change.

Reports

Read our recent report "Leading participatory monitoring processes through a gender justice lens for Green Climate Fund financed projects" here.

Partners:

Related projects

Latest News

Letter to Green Climate Fund Board: Improve Decision Making

Letter signed by 70 international civil society organizations: As members of civil society following the Green Climate Fund (GCF), we are writing to express our concern about the way the Board reached some of its most important decisions during the 14th Board Meeting (B.14). We would also like to share some thoughts on how to improve upon this process in the future. We are especially referring to the practice of “package approval” that was used to approve funding proposals and new accredited entities. Weak process. The Board approved 10 proposals worth $745 million without discussing each one separately. The Board’s assessment of each of the funding proposals should be made individually and with the utmost care, to ensure that the objectives, principles, policies, and operational modalities of the Fund are respected and complied with. Furthermore, there was no opportunity for active observers to highlight individual comments for each of the funding proposals (they could merely air some concerns during the overarching discussion of all funding proposals). The same can be said with regard to the package approval of eight accredited entities. There was no public discussion of the merits and/or shortcomings of each approved applicant entity and no possibility of civil society input. Civil society has vital contributions to make, and for our engagement to be meaningful, active observers must be given the opportunity to share important points regarding each proposal and accreditation application during Board meetings. Indeed, the Board’s way of working has actually been in conflict with the GCF’s own Governing Instrument, which states that “the Fund will operate in a transparent and accountable manner”. Approval despite clear failures of GCF policy compliance. The Board repeatedly overlooked the failure of a number of proposals to comply with GCF policies and procedures. For example, public notification for a number of projects was out of compliance with the Fund’s information disclosure policy, which requires a 120-day notification period for proposals with high social and environmental risk. Mandatory gender action plans were missing from several projects, and stakeholder consultations in some cases were highly inadequate. Yet the Board approved all of the projects with one package decision. The Board even pushed through proposals without the requisite guiding policy in place. For example, programs to be implemented via sub-projects were approved, yet the GCF does not have a policy regarding whether or not high risk sub-projects must come back to the Board for approval. We believe they should, to ensure the GCF’s accountability, and to preempt some of the serious environmental, development, and social shortcomings widely seen at other multilateral institutions that finance sub-projects via financial intermediaries. Precedent-setting. While the Board stated that “the approach taken to approving funding proposals at B.14 does not constitute a precedent,” we are concerned that, at this point, the Board has taken such an approach multiple times. Steps to put a stop to these modalities becoming the de facto modus operandi must be taken in the lead up to B.15, including: Timely public disclosure on the GCF’s own website that, at minimum, follows GCF rules (i.e. 120 days for ESIAs for high risk funding proposals, 30 days for medium risk, and three weeks prior to board meetings for all other materials). All annexes and the Secretariat’s due diligence should also be disclosed for funding proposals; Publication of applications for accreditation as soon as they are filed, as well as operationalization of formal mechanisms for third party input (from affected communities, indigenous peoples, civil society, etc.); Individual consideration of each funding proposal and each applicant for accreditation during public sessions of the Board; Opportunities to consider civil society interventions during the debate on each individual proposal, rather than at the end of agenda items; Where formal (or informal) working groups are established to consider conditions to be placed on proposals, there should be a clear process to allow the consideration of civil society feedback, at a minimum in writing, but preferably through the direct participation of the CSO active observers or their alternates; Discussions on more complex and/or controversial proposals require several rounds of debate. In these cases, civil society observers should be given the opportunity to make further interventions responding to new proposals, conditions and amendments. Civil society observers are committed to working with the Board to improve the accountability and transparency of Board decisions, in particular on funding and accreditation approvals. As a learning institution, the GCF needs to take the time to look at the merits of individual proposals and applicants in order to clearly elaborate how they can support the paradigm shift in recipient countries. We therefore urge the Board to better prioritize valuable time during the upcoming Board meetings to allow for meaningful discussions.

Read more

The Green Climate Fund: Summary of Decisions of the Board of Directors (in Spanish)

This report offers an overview of the development, evolution and current state of the Green Climate Fund. It includes a summary of the decisions made thus far by the Board of Directors. It also highlights the progress made by the Fund, and the challenges it must overcome in order to achieve its objectives. In 2010, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change created the Green Climate Fund with the goal of contributing significantly and ambitiously to the goals set by the international community to combat climate change. The Fund will be the primary mechanism through which developing nations receive financial resources from developed nations to undertake adaptation and mitigation activites that will help them confront extreme changes in climate. The Latin America nations that are members of the Convention will be beneficiaries of the financing. That’s why a clear understanding of the objectives and operation of this institution can contribute to better use of these resources in the region. Download the report (in Spanish)

Read more

Remembering Berta Cáceres before the Green Climate Fund

On March 3, Berta Cáceres, an indigenous rights defender in Honduras, was assassinated. As a leader of COPINH, Berta was fighting against the implementation of an internationally funded large dam project. She was fighting for the health of the Gualarque River, and for the lives and livelihoods of the indigenous communities that depend upon it. Her death is a glimpse at the real life impacts that megaprojects may have. That’s why, at the closing of the 12th Meeting of the Board of the Green Climate Fund, I presented a message to the Board on behalf of the civil society organizations monitoring the development and decision making process of the mechanism. The message was intended as a reminder of the care with which financing decisions must be made, as the board prepares to review and approve more projects: “We would like to ask for a moment to remember Berta Cáceres, the indigenous environmental justice and human rights defender brutally murdered last week in Honduras. She was leading a fight against an internationally financed large dam that threatened her water, her land, and her people. We would like to ask all of you to do whatever you can to secure justice for Berta, and the immediate safe return of Gustavo Castro, head of Friends of the Earth Mexico, who was injured during the assassination and whose life is now in danger. Berta’s murder serves as a tragic reminder to the GCF of the incredible risks faced by rights defenders, and the deep need to safeguard their rights and the rights of the people and land they fight for. The GCF must not support questionable projects like the one that claimed her life and must obtain in all of its projects and programmes the free, prior and informed consent of people and communities to protect their livelihoods and survival.”

Read more