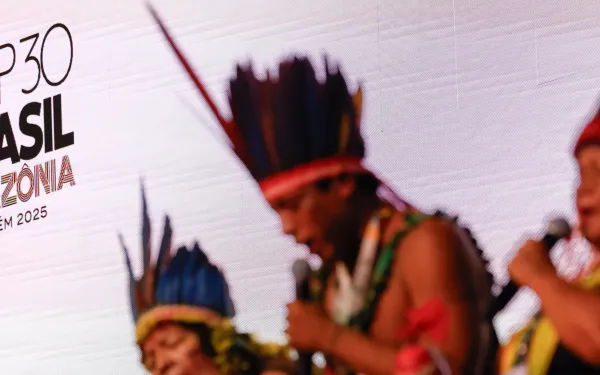

With more than 25 hours of delay, the 30th UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) has come to an end. The so-called "Amazon COP," held in the Brazilian city of Belém do Pará, leaves behind disappointment for failing to change course, but also some advances that can help push climate action forward. It was not a total failure: multilateralism remains intact, though battered.COP30 was marked by the presence of Indigenous peoples, especially from the Amazon basin, who filled the streets and side events. However, according to reports, only a fraction of these delegations gained access to the formal negotiation rooms, while a disproportionate number of representatives from the fossil fuel industry participated in the official event. This imbalance reflects the democratic health of the climate regime: at the Amazon COP, the power of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples was felt in the streets, but their voices remained underrepresented in decision-making spaces.A few days into the conference, the latest synthesis report of updated nationally determined contributions was released. Its message was more bitter than sweet, but it offered one important takeaway: although the gap to keep global warming below 1.5°C remains enormous and complex, the report confirms that the Paris Agreement has indeed helped steer the challenge. We are in a better position than in a scenario without the agreement: projected emissions growth has been slowed, though not nearly enough.At this point, it is clear that COPs will not "save the world," but it also seems impossible to overcome this crisis without the cooperative platform they provide. From that perspective, it is worth asking what COP30 leaves us. The approved agreement: Global MutirãoThe word "Mutirão" references the spirit of collective effort—body and soul—that Brazil sought to bring to the international negotiation process at this COP.The approved agreement reiterates the goal of keeping the planet’s temperature increase below 1.5°C, acknowledging that time is running out. To that end, it proposes two voluntary mechanisms, led by the Presidency, which for now seem more like statements of good intent than tools with teeth: a "Global Implementation Accelerator" and the "Belém Mission for 1.5°C."On financing, the text establishes a two-year work program on Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which concerns the public resources developed countries must provide, understood in the context of Article 9 as a whole.A footnote was added to clarify that this does not prejudge the implementation of the new global goal. Civil society organizations warn that this formulation risks further diluting developed countries’ specific obligations under the narrative of "all sources of financing," without clear rules on who must actually provide the resources and under what conditions. The real value of all this remains to be seen in practice. What was gained: A new mechanism for a just transitionA major achievement of COP30 was the adoption of the Belém Action Mechanism (BAM), a new institutional arrangement under the Just Transition Work Programme. It was the main banner carried by organized civil society.The mechanism is designed as a hub to centralize and coordinate just transition initiatives around the world, providing technical assistance and international cooperation to ensure the transition does not repeat the mistakes of the fossil era.The text incorporates many of the principles championed by Latin American civil society—including human rights, environmental and labor protections, free, prior and informed consent, and the inclusion of marginalized groups—as essential elements for achieving ambitious climate action.Even with gaps in safeguards and governance definitions, the BAM is a concrete step forward for this COP on climate justice. It creates a starting point to discuss not only whether there will be a transition, but how it will be done and under what rules, so as not to replicate the logic of the fossil economy. Its design and implementation will be debated at upcoming COPs, where it will be crucial for the region to arrive with solid, united proposals. Ending fossil fuels and deforestation: Two “almosts” that move us forwardAn agreement to leave behind fossil fuels and end deforestation—directly addressing the main drivers of the climate crisis—"almost" made it into the final decision.More than 80 countries from both the global north and south called for a roadmap to exit oil, gas, and coal. More than 90 supported a roadmap to stop and reverse deforestation by 2030. Although these requests made their way into drafts of the closing decision, they disappeared from the final text after resistance from major fossil fuel producers.Still, we do not leave empty-handed: Brazil, as COP30 Presidency, announced it will advance these roadmaps outside the formal framework of the UNFCCC. For the fossil fuel phaseout, Colombia committed to co-organize, with the Netherlands, the first global conference on the topic in April 2026.Although these items were not secured within the official negotiations, it is worth celebrating that—for the first time—such a broad coalition of countries united to achieve them. These two "almosts" matter: they set a new political and legal baseline for the rounds ahead. Two tools to advance adaptationCOP30 delivered tools to keep adaptation negotiations moving forward.The Mutirão decision calls for tripling collective adaptation finance by 2035, tied to the $300 billion USD per year agreed under the new global goal. This falls short of what the poorest countries asked for (tripling by 2030, with an explicit figure) and lacks clarity or guarantees regarding the role of developed countries. But it is a political anchor worth building on.At the same time, a first package of 59 indicators was adopted for the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). Several African countries and experts described them as "unclear, impossible to measure, and in many cases unusable," because they sacrifice precision and grounding in community realities in order to unblock the agreement. In response, the text included the "Belém–Addis Vision," a two-year window to correct flaws and make the framework operational by 2027.In short, we have more promises of money and an indicator framework weaker than necessary, but also a process through which the region can continue pushing for a useful GGA and for fair, sufficient adaptation finance. Loss and damage: Slow and uncertainProgress on this issue has been painfully slow compared with the urgency of the problem. At COP30, the third review of the Warsaw International Mechanism was finally approved. The result is frustrating: discussions have taken a decade while communities are already paying the cost of warming.On the other hand, the Loss and Damage Response Fund, created two years ago, issued its first call for proposals, with an initial package of $250 million USD in grants available over the next six months. The Fund has $790 million USD pledged, but only $397 million USD actually deposited—an enormous gap compared to the hundreds of billions estimated annually for developing countries.The expected political pressure for developed countries to scale up contributions was largely diluted in the final text, although the Fund was at least linked to the new global financing goal agreed at COP29. A new Gender Action PlanCOP30 concluded with the adoption of a new Gender Action Plan under the renewed Lima Work Programme. The Plan identifies five priority areas: capacity-building and knowledge; women’s participation and leadership; coherence among processes; gender-responsive implementation and means of implementation; and monitoring and reporting. It also provides a roadmap to ensure climate action is truly gender-responsive, with indicators to track progress. Methane: A super-pollutant still lacking the spotlight science demandsAt COP30, short-lived climate pollutants—especially methane—gained visibility thanks to a dedicated pavilion and dialogues with regional and global actors. The Global Methane Status Report 2025 was also presented, noting “significant” progress since the 2021 launch of the Global Methane Pledge. However, it warns that current progress remains far from the goal of reducing methane emissions by 30% by 2030.In the official negotiations, the draft of the Sharm el-Sheikh Mitigation Ambition and Implementation Work Programme included an explicit reference to methane mitigation through proper waste management, but that mention was removed from the final text, leaving only a general call to improve waste management and diminishing the focus on the urgent need to reduce emissions of a pollutant whose mitigation is essential to achieving the Paris Agreement goals. Still, during COP30, the global “No Organic Waste (NOW) Plan to Accelerate Solutions” was launched, aiming to reduce methane emissions from organic waste by 30% by 2030.Overall, this COP missed a crucial opportunity to advance its core objective. If we truly want to stay on track with the Paris Agreement, we must treat methane as what it is: a decisive opportunity we are still not seizing. How we close COP30 and prepare for the nextCOP31 will be held in Turkey, under the presidency of Australia. And despite the shortcomings of COP30, there are at least four things to defend and build on:The normalization of the debate on phasing out fossil fuels, with more than 80 countries openly calling for a roadmap and Colombia–Netherlands taking that discussion to a dedicated conference in 2026.A forest agenda that, although left out of the text, carries the promise of a Brazilian roadmap and explicit support from a wide group of countries.A small but real advance on adaptation, with the decision to triple finance and a first set of indicators that, while weak, offer a basis to push for improvements.The creation of a new mechanism for a just transition, which can shape how the transition unfolds—bringing together and strengthening efforts that support and protect workers, communities, and Indigenous peoples.

Read more