Blog

Latin America advances on climate change

Though the United States is no longer committed to the fight against climate change, Latin America is making much needed progress. Countries throughout the region are beginning to take the protection of nature seriously, evident through new laws and sustainable projects. But we still have a long way to go. Latin American is home to more than half the biodiversity on the planet. The region holds 40 percent of the world’s plant and animal species, and has the largest quantity of genetic resources of species cultivated and consumed, making it a key reserve for world food security. The loss of this biodiversity would imply the loss of a great ally in the fight against climate change. The region’s abundant green areas capture excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, allowing for climate regulation. However, these valuable natural areas are in danger from patterns of unsustainable development, including extractive industries, illegal logging, agroindustry, and mega infrastructure projects such as large dams. The United States, one of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases, has denied the very existence of climate change, and has turned it’s back on global efforts to find effective solutions. So now it’s up to the rest of the world. Some Latin American governments, thankfully, have been taking the lead by adopting laws, implementing policies, and jumpstarting projects that are fundamental to countering extreme changes in climate. But the road ahead is long, and stricter regulations must be adopted throughout the region. Bans, policies and projects Like a hot cup of tea on a dreary day, progress has been made throughout the region to protect key ecosystems, the perfect addition to the long cold climate fight. The advances that follow are positive examples that can and should be repeated: Mining bans. Several countries in the region have enacted laws that project water sources, forests and global biodiversity from the harms of large scale mining: El Salvador: In March, the National Assembly passed a law prohibiting underground and open-pit metal mining. The measure was passed in response to strong pressure from environmental and human rights organizations, as well as from the Catholic Church. Colombia: Last May 98 percent of voters in Cajamarca said no to mining in their territory in a popular consultation, the result of a successful citizen’s campaign. Wetland Protection. Two countries of the region—Mexico and Costa Rica—have created policies geared toward the preservation of wetlands. Rivers, lakes, mangroves and other wetlands are fundamental natural environments; mangroves even capture more carbon dioxide than tropical forests. Protected Areas. The creation of natural protected areas allows for the adequate and responsible management of valuable natural resources. Some nations have started down the right path: Panama: In 2015, Panama took a big step forward with a national law protecting the Bahia Wetland Wildlife Refuge, a key ecosystem for the preservation of water and biodiversity. Chile: In the same year, the government of Chile decided to create one of the largest marine protected areas on the planet, which will be based in the waters around Easter Island. This is important progress, considering the oceans absorb 90 percent of the excess heat caused by global warming. Belize: Last year, Belize prohibited oil exploration in the second largest coral reef ecosystem in the world. Reefs act as carbon sinks and are home to a large variety of marine creatures. Green projects. Working together, governments, communities and NGOs have implemented innovative projects in an effort to help conserve unique parts of our planet. Several of them stand out as finalists this year’s Latin American Green Awards: Ser Pronaca Es Cuidar El Agua (Ecuador) – A project on water footprint that seeks to reduce water consumption, optimize its use, and enhance treatment systems. Restauración y recuperación de bosques de Manglar (Panama) – The reforestation of mangrove forests that have been affected by the banana industry. Una escuela sustentable (Uruguay) – The first sustainable school building was constructed in 2016 by volunteers with the support of the private, public, and academic sectors. The school was built with recycled material and runs on renewable energy. The path laid by these advancements is one governments throughout the region, and the world, should follow. But much work, and little time, remains. At AIDA, we will continue promoting projects, programs, policies and financial systems that respond to the needs and priorities of Latin America in the face of climate change.

Read more

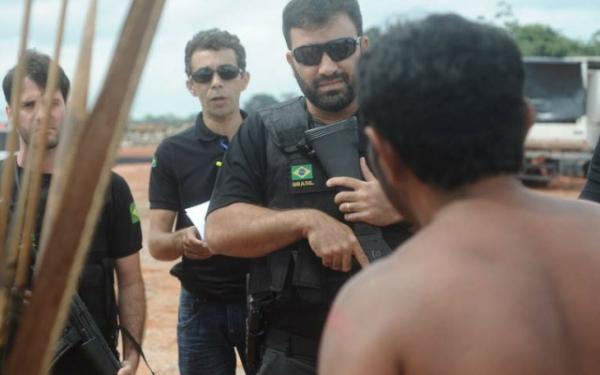

In Colombia, the power to stop fracking lies with the people

In Colombia’s fight against fracking, one tiny town is putting up a big fight. Since early 2016, the residents of San Martín, 300 miles north of Bogotá in the department of Cesar, have mobilized, protested, and peacefully resisted the government’s plans to begin fracking in their municipality. By staging marches and protests, and forcibly blocking oil company employees from accessing fracking exploration sites, concerned citizens are raising their voices against an environmentally destructive industry. But San Martín is just one municipality of many affected by the fracking fever now sweeping Colombia’s oil and gas industry. Colombia has vast reserves of unconventional fossil fuel deposits trapped in tight deposits of shale rock. Fracking breaks up that rock—using a mixture of water, sand and chemicals—and releases those deposits, which analysts say could produce 6.8 billion barrels of oil and 55 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, according to the US. Energy Information Administration. That’s enough to satisfy the country’s energy demand for decades. While operations have not yet begun in Colombia, to date 12 blocks have been reserved for fracking exploration, according to the National Hydrocarbon Agency, and one concession has been granted to a multinational corporation. These fracking sites are expected to affect municipalities all across the country. Colombia has followed the lead of other Latin American countries that have embraced fracking as a quick and dirty fix to their fossil fuel addiction, which feeds energy-hungry populations. Currently, Mexico, Argentina, and Chile are the region’s fracking powerhouses. Colombia “can’t afford not to frack,” said Juan Carlos Echeverry, the then President of Ecopetrol, Colombia’s state oil company. But San Martín’s residents—along with many other Colombians concerned about the future of their communities, their country, and the planet—have a different opinion. In support of the citizens of San Martin, CORDATEC has been organizing an on-the-ground resistance to limit fracking exploration in Cesar. Another organization, the Alianza Colombia Libre de Fracking is also fighting back: it recently signed an open letter asking President Juan Manuel Santos to pass a moratorium on fracking. While these efforts are integral to the fight against fracking, it’s also necessary to fight the battle on the local level. Wherever possible, cities and municipalities can use creative solutions like strict zoning laws or referendums to achieve fracking bans locally. This technique has seen significant success in Brazil, where more than 70 municipalities have passed fracking bans, simultaneously stalling the spread of the fossil fuel industry and protecting their environment. In the United States, states like New York, Maryland, and parts of California have also banned fracking. In partnership with organizations throughout the region, AIDA is working diligently to stop the spread of fracking in Latin America. Through the Alianza Latinoamericana Frente al Fracking and the Red por la Justicia Ambiental en Colombia, we’re focusing on local solutions with potentially regional implications. “The Alianza works to promote public debate, awareness, and education among civil society organizations in Latin America,” said Claudia Velarde, AIDA attorney. “We also support local resistance efforts against the spread of fracking in the region.” The Alianza is petitioning for a hearing before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, in which they’ll demonstrate the impacts fracking has on the human rights of affected communities. If our governments are committed to continuing to drill for fossil fuels, it’s time for local communities to stand up and demand a future of clean, renewable energy. By focusing our power at the grassroots level, like the people of San Martín, we too can demand a better future and push back against the fossil fuel industry.

Read more

Berta lives: Keeping the struggle alive, despite the risks

On June 30, Berta Zúñiga Cáceres, the daughter of murdered Honduran environmental activist Berta Cáceres, survived an attempt on her life. She was traveling home with two colleagues when men wielding machetes stopped her car. As the men raised their weapons, Zúñiga’s driver hit the gas and swerved around the attackers, but not before one assailant hurled a large rock that struck their windshield. The attackers pursued the activists, attempting to run their car over the edge of a cliff. Fortunately, Zúñiga and her colleagues narrowly escaped. Six days later, FMO and FinnFund, two European development banks, announced their official withdrawal from the Agua Zarca dam, which Zúñiga is fighting because it would flood a site sacred to indigenous Lenca communities. “The timing of our exit announcement is not related to the attack on Ms. Berta Zúñiga Cáceres,” FMO spokesperson Christiaan Buijnsters said. “It is coincidental.” In a press release, FMO and FinnFund said the exit was “intended to reduce international and local tensions in the area.” Before she was assassinated in her home in 2016, Berta Cáceres campaigned forcefully against the dam, winning the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize for her work. Zúñiga, 26, took over her mother’s leadership role in the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH) in June 2017. Environmental activists in Honduras are still fighting the dam, but the Central American Bank for Economic Integration has yet to pull its financial support for the project. “I was born into a people of great dignity and of great strength,” Zúñiga said in an interview with independent US news outlet Democracy Now. “My mother, Berta Cáceres, instilled in us from a very young age that the struggle is rooted in dignity and that we must continue forward defending the rights of our people.” Systems of corruption and impunity The attack on Zúñiga is the latest in the world’s most dangerous region for environmental defenders. In Honduras, between 95 and 98 percent of crimes go unpunished. Collusion between governments and corporations often shields the assassins and those who hire them to stifle environmental and human rights activists. Unfortunately, families of murdered activists like Cáceres rarely see justice. But there is still hope. Following a global outcry after Cáceres’ death and demands for an investigation, nine people were arrested in connection to her murder. Some are connected to Desarrollos Enérgeticos, S.A., the company constructing the Agua Zarca dam. Court documents also suggest the assassination was planned by military intelligence specialists linked to Honduras’ US-trained Special Forces. Despite these arrests, the major orchestrators of the assassination have yet to be charged. COPINH has denounced the hearings in the case, claiming that the government’s prosecution is full of flaws and irregularities. Meanwhile, killings and attacks like the one on Zúñiga continue. “We know that in Honduras it is very easy to pay people to commit murders,” Zúñiga said to TeleSur in 2016. “But we know that those behind this are other powerful people with money and a whole apparatus that allows them to commit these crimes.” Yet Zúñiga and COPINH remain undeterred from their fight. “We are going to continue forward in our struggle,” Zúñiga said to Democracy Now. “Part of our struggle is to break this cycle of impunity.” She is motivated by her mother’s advice: “Let us wake up, humankind! We’re out of time. We must shake our conscience free of the rapacious capitalism, racism, and patriarchy that will only assure our own self-destruction… Let us build societies that are able to coexist in a dignified way, in a way that protects life. Let us come together and remain hopeful as we defend and care for the blood of this Earth and of its spirits.” If we take those words to heart, the struggle for a greener and more just world—along with the spirit of Berta Cáceres—will live on.

Read more

Belo Monte: Hope remains, despite failed promises

When the Belo Monte Dam builders came to this corner of the Brazilian Amazon, they came with the promise of sustainable development, particularly for Altamira, the city closest to the dam. On a recent visit to that city, it was clear to me that—six years after construction began and one year after beginning operations—Belo Monte has brought anything but. Last June, Brazil’s Institute of Applied Economics classified Altamira as the most dangerous city in Brazil. According to the study, Altamira’s rapid and disorderly growth over the last six years has had serious implications for crime in the city. In 2000, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, Altamira had about 77 thousand residents. With dam construction, that figure soared to 110 thousand last year. The result: Altamira registered the country’s highest homicide rate in 2015, with 105.2 murders per 100 thousand people. A troubling context frames these numbers: Brazil is the most dangerous country in the world for environmental defenders, according to Global Witness. That’s especially true for those who dedicate their lives to defending the Amazon—16 of Brazil’s 49 murders in 2016 were related to protection of the Amazon rainforest. Unsanitary conditions In addition to generalized violence, the other big worry in Altamira is basic sanitation, which involves sources and systems of clean water, as well as waste management. During the last six years, when the dam completely altered the urban and social dynamic of the city, no one bothered to provide an adequate, basic sanitation system. And that’s despite the fact that dam construction and operation were approved on condition of building such a system. The only thing built in Altamira at that time was the massive hydroelectric dam. In April of this year, a Brazilian court ordered the dam’s operations suspended until basic sanitation is adequately provided to the resettlement districts of Altamira. But the company in charge of the dam has refused to comply with the ruling, arguing that it has permission to operate. This clearly demonstrates the government’s inability to avoid the abuses caused by this mega-project and its operating company. Questionable investment The current reality of Belo Monte is aggravated by the fact that a Chinese state-owned company, Grid Brazil Holding, won the auction to take over the second power transmission system to be fed by the dam. The company offered 988 million reales (roughly $300 million USD), which makes me question the previous statements of the Brazilian government that hydroelectric energy is cheap, as well as clean. This investment is worrying because the company has already been fined several times for failing to meet deadlines related to the first power transmission system. Worse still, Chinese companies are known for failing to protect human rights and the environment, which is why the situation in Altamira is likely to become even more complicated. Hope remains Despite this discouraging panorama, the urban population, as well as the indigenous and riverside communities, still have hope that Altamira will one day be a quiet and beautiful city again. I heard many people speak of their desire to return to the days of sitting on chairs in the street talking with neighbors, and bathing in the waters of the Xingu river; the days of collective fishing and parties in the parks. Those people have shown me that we should not be afraid or lose hope. There are many who believe in my work as a defender of the Amazon. It is for them that I will keep fighting. I will work so that institutions, like the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, before which our case is pending, hold Brazil accountable for the human rights violations that have occurred from the construction and operation of Belo Monte. And I will ensure that the people affected by Belo Monte get justice and reparations.

Read more

As killings increase, how can we defend the defenders?

Of the 87 human rights defenders murdered in Latin America in 2016, 60 were defending rights linked to environmental destruction. That’s according to a new report from Global Witness. Worldwide, at least 200 environmental defenders were killed in 2016, making it the most dangerous year for environmentalists on record. And 60 percent of these murders occurred in Latin America. Disturbingly, these statistics likely underrepresent the problem, as many killings of defenders and activists around the world go unreported. Environmental defenders are also frequently subjected to harassment, intimidation, death threats, arrests, sexual assault, kidnapping, and lawsuits intended to silence them. “The battle to protect the planet is rapidly intensifying and the cost can be counted in human lives,” Global Witness campaigner Ben Leather said. “More people in more countries are being left with no option but to take a stand against the theft of their land or the trashing of their environment. Too often they are brutally silenced by political and business elites, while the investors that bankroll them do nothing.” The roots of the problem Why are so many activists under threat, simply for speaking out and raising awareness about environmentally destructive projects? Governments argue that mining, oil and gas extraction, logging, and dams will boost their countries’ economy. But corporations typically hire outside contractors, creating few if any local jobs. And in many situations, development projects pollute the environment, displace entire communities, and infringe human rights. Some projects, like large hydroelectric dams, also hurt biodiversity and contribute to climate change. Furthermore, governments must often rely on transnational corporations or foreign investment to fund these projects. As a result, profits from mining, oil and gas, or large dams often benefit international corporations or a country’s most-wealthy businessmen, but are not always invested into local communities. This situation produces extreme rates of economic inequality. Honduras, for example, is one of the most unequal countries in Latin America and has had the highest per capita rate of killings of environmental defenders over the last decade. Twenty percent of the wealthiest people in Honduras reap 60 percent of the national income, leaving almost two-thirds of Hondurans to live in poverty or extreme poverty, according to the Organization of American States. When activists—many of them indigenous—speak out against these environmental and economic injustices, they’re often denounced as enemies of progress. Working together, governments and corporations try to silence outspoken defenders. When censorship is not enough, the military, police, and mercenaries are called to silence the opposition with escalating threats and violence. How to defend the defenders Each year, as the problem intensifies, we’re reminded of our duty to stand up for environmental and human rights defenders, and of the need to institute adequate policies for their protection. Here are several ways governments and citizens alike can protect defenders around the world: International Law. Governments around the world are party to international treaties and conventions that obligate them to uphold certain human rights standards. When these basic rights aren’t respected, it’s up to the international community to step in and protect activists under threat by pressuring governments to enforce the law. AIDA works in this way to hold governments accountable and encourage the immediate adoption of measures to guarantee the life and integrity of at-risk activists. “States must guarantee a favorable environment in which people can safely perform their work to protect the natural world,” AIDA attorney Astrid Puentes Riaño said. “States should also investigate these instances of violence. The murders of those who bravely defend the environment must not go unpunished.” Domestic Legislation. When international pressure doesn’t work, domestic laws can help pressure States into protecting activists who speak out. In the United States, for example, legislation has been proposed that would suspend US military and police aid to Honduras until the Honduran government investigates human rights violations in the country. The bill could help protect activists there and serve as an example for other countries that would like to follow suit. Emergency Measures. Emergency visa measures or diplomatic protections to remove endangered activists from harm can be useful in relocating activists across borders or protecting them in another way. Global Solidarity Campaigns. Solidarity campaigns organized by coalitions of human rights organizations and supported by the media hold great potential. If these outlets simultaneously, consistently, and reliably raised the alarm of an activist under threat, governments and corporations might think twice before trying to silence the person at risk. This, of course, involves you too. There’s no substitution for the mobilization of community support—in the streets, on social media, in your daily life. Standing up, speaking out and raising awareness is the first step toward building a more just future. These are just some of the solutions to this growing problem, and their success depends on all of us. Showing we’re not afraid to fight for environmental justice and a future that respects everyone’s human rights is not just a good idea, it’s necessary for our survival.

Read more

Shark conservation is at risk in Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, it’s now up to the government to decide the future of endangered hammerhead sharks. If the government halted the export of all hammerhead shark products in the next year, it could stave off extinction of these amazing creatures. That’s the recommendation of Costa Rica’s Scientific Advisory Council for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. The Convention is an international agreement to prevent trade from threatening the survival of wild animals and plants. Of the nearly 100 species of sharks and rays in Costa Rica, 15% are in danger of extinction due to overfishing and environmental destruction or degradation. Hammerhead sharks were listed as an endangered species in 2014 and have lost up to 90% of their population. In response, the Scientific Advisory Council recommended in April 2017 that Costa Rica should prohibit export of hammerhead products for at least one year, or until the country reduces hammerhead fishing and the health of the species improves. The role of the fishing industry Shortly after the Scientific Advisory Council made its recommendation, the Costa Rican government issued an executive decree. The Costa Rican Institute of Fishing and Aquaculture (Incopesca) and the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock were given authority over the export of products made from threatened or endangered sharks. However, both government agencies favor the fishing industry over marine conservation, according to Mario Espinoza Mendieta, researcher from the University of Costa Rica and member of the Convention’s scientific council. “This dynamic tips the balance in favor of the production sector,” Espinoza said. Incopesca’s Board of Directors represent various fishing interests across the country—a position that does not always align with the protection and sustainable use of marine resources, according to Espinoza. Recently, Incopesca was questioned because it failed to prosecute shrimping boats that were illegally fishing in protected waters. Shark commerce While exporting shark products is permitted within the regulations established by the Convention, shark finning—the practice of cutting fins and throwing the shark back into the ocean—is illegal in Costa Rica. Considered a delicacy in some Asian countries, shark fins are often valued at upwards of $100 per kilo. Last February, a Costa Rican court issued the first felony criminal sentence for shark finning against a Taiwanese businesswoman who was found in a port with illegally harvested shark fins. Using international law, AIDA and Conservation International worked with Costa Rica’s Public Prosecutor to help resolve the case. A responsible decision The governments of Colombia and Ecuador have developed campaigns to protect hammerhead sharks. But in Costa Rica, Incopesca is responsible for the future of the species and will hopefully take the Scientific Advisory Council’s recommendations into account. Because the hammerhead’s numbers are so low, it may only take one bad decision to cause their extinction. Other species, including the gray shark, are also at risk from the fishing industry. If Costa Rica wants to preserve its natural wealth for the future, it should set an example of preservation by putting principles of sustainability over economic gain.

Read more

Chilean chum: How eating salmon in the US hurts Patagonia’s coastal wildlife

After two years of vegetarianism, the Texan in me decided that an entirely plant-based diet was not going to work. The experience, however, taught me to consume meat ethically. Wherever possible, I now choose organic and sustainable “farm to table” meat and poultry. But when it comes to my favorite seafood—salmon— “farm to table” can take on a whole new meaning. Salmon is one of the most popular seafoods in the United States, and over a third of all salmon in the U.S. comes from Chilean salmon farms, which raise the carnivorous fish in off-shore enclosures along the Patagonian coast. Although salmon is healthy—it’s loaded with omega-3 fatty acids and B-vitamins—increased U.S. demand for salmon is having an unhealthy impact on Chile’s environment. These farms endanger delicate coastal ecosystems, contribute to oceanic pollution, and threaten marine life along the pristine Magallanes shoreline. Chile is the second largest global exporter of the fish, and salmon farming is one of the country’s largest industries. Today, that industry is growing. There are already over 100 salmon farms operating in the Magallanes and, as of March 2017, plans for 342 more were in the works. Driving this expansion is a booming worldwide salmon market. But even though the U.S. boasts a salmon industry of its own and wild-caught Alaskan salmon is considered some of the best in the world, U.S. consumers ate over 144,000 tons of farmed Chilean salmon in 2016, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A fishy situation While fish farms are one solution to the many problems associated with overfishing, Chile’s unregulated salmon industry has serious environmental side-effects. These salmon farms disrupt their environments because overpopulated waterways create anaerobic conditions that deprive the local wildlife of oxygen. Often treated with excessive amounts antibiotics and pesticides, uneaten salmon feed and salmon feces also pollute coastal seafloors and introduce chemicals into the environment. Because they are not native to the southern hemisphere, salmon that escape their pens can disrupt local food chains. Salmon also frequently die in their enclosures, and the decomposing fish raise levels of ammonia in the water. Although research is still underway, scientists speculate that higher concentrations of ammonia, along with El Niño weather patterns and warming oceans caused by climate change, may be responsible for Chile’s recent “red tides.” These toxic red algae blooms kill coastal wildlife by the millions, inundating Chilean shores with dead fish (including salmon), birds, and whales. To fight back against this destructive industry and the harmful impacts of globalized seafood trade, AIDA filed a claim with the Chilean government expressing concern that salmon farms are harming local ecosystems. “We want to improve the way things are being done by aiming for sustainable development that will not ruin the fragile ecological balance of the Patagonian seas,” AIDA attorney Florencia Ortúzar said. AIDA also recently began a petition asking that Chile investigate the damage caused by salmon farming in the Magallanes and sanction those responsible. You can sign the petition here. New migration routes Today, the U.S. salmon industry practices catch and release: it is known for producing high quality fish, yet 80 percent of Alaskan wild salmon is traded away. So why does the U.S. produce some of the world’s best salmon, but consume some of the world’s most environmentally harmful fish? The answer, in short, is globalization. Filleting and de-boning salmon is a process too delicate to mechanize as in other meat industries. Because labor is cheaper in Asia, U.S. salmon is shipped to processing plants in China, which then re-distribute the processed fish across the region. While some of that salmon makes it back across the Pacific, the U.S. market is flooded with cheaper farmed salmon from around the world. Now, Chile’s industry “is facing competition from Canada and Norway,” according to trade analysis group Datamyne. After expressing concerns over high levels of antibiotics in Chilean fish, U.S. retail giant Costco decided in 2015 to stock Norwegian salmon instead, further muddying the waters in the U.S. salmon trade. To make matters worse, a study by conservation nonprofit Oceana concluded that nearly 43% of “wild” salmon sold in the United States was misidentified. While it is difficult to tell whether farmed salmon is mislabeled as “wild” during trade or once it shows up on the menu, lax labeling laws in the U.S. make it difficult to tell exactly where that salmon steak came from. So for seafood lovers like me, there may be few good options for eating salmon sustainably, besides taking up fly fishing. But for the sake of protecting Chile’s coastal wildlife, maybe it’s time U.S. consumers make their voice heard. If we’re going to import salmon from Chile, we should at least demand the country regulate its farms to be more environmentally friendly. Maybe it’s also time the U.S. salmon industry started keeping its catch in its own boat. Sign the petition to protect Patagonia’s Magallanes coastline here.

Read more

Spending climate dollars on large dams – a bad idea

During its last board meeting, the Green Climate Fund—charged with financing developing nations’ fight against climate change—approved two projects related to large dams. That means $136 million will finance large-scale hydropower, contradicting the Fund’s goal of stimulating a low-emission and climate-resilient future. We’ve said it before: large dams are not part of the paradigm shift we need. They worsen climate change and are highly vulnerable to its impacts. They also cause grave economic and socio-environmental problems that make it impossible to label them as sustainable development. dam Projects before the gcf While the two projects will exacerbate climate change, they aren’t the most destructive we’ve seen. The first is expected to generate 15 MW of electricity in the Solomon Islands, an impoverished Pacific archipelago highly vulnerable to climate change. Planned for the Tina River, the dam will be the country’s first major infrastructure project. Today, the Solomon Islands rely almost entirely on imported diesel to produce energy. It is an unreliable, highly polluting energy source for which residents must pay one of the highest rates in the region. We would have liked to see the Solomon Islands leapfrog toward a more sustainable alternative, avoiding the era of large dams altogether. But we were pleased to see the World Bank’s consultation and engagement processes with local communities, which lend legitimacy to the project. The second project will rehabilitate a dam built in the 1950’s in Tajikistan. The repairs will make the dam more resilient to weather and less subject to accidents. Since it is focused on rehabilitation, the project will not generate the socio-environmental impacts typical of ground-up dam construction. Tajikistan already gets 98 percent of its energy from hydropower, an increasingly unreliable energy source. In fact, during colder months, when more energy is needed, more than 70 percent of the population suffers cutbacks due to the malfunctioning of dams. It’s unreasonable to use climate finance to deepen a country’s energy dependency instead of diversifying its matrix and increasing its climate resiliency. Our Campaign against large dams When we learned that large dam proposals would come before the Fund, just before the 14th meeting of the Board of Directors, we drafted a letter explaining why large dams are ineligible for climate funding. Then, in anticipation of the 16th meeting, during which the projects would be discussed, we sent Board Members an informational letter on each of the projects, signed by our closest allies. Finally, during the board meeting, we circulated a statement signed by a coalition of 282 organizations, further strengthening our position against the funding of large dams. We obtained official replies from several members of the Board, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (in charge of the project in Tajikistan), and the Designated National Authority of the Solomon Islands. Delegates from Canada and France requested further discussion of the issue. The problems with large dams received international media attention through articles published in The Guardian and Climate Home. Advancing with Optimism Although financing was ultimately granted to both of the projects, we managed to draw international attention to the contradiction inherent in funding large dams with money designated to combat climate change. Several members of the Green Climate Fund expressed doubts about further promoting large hydropower initiatives. We’re confident they’ll raise their voices when faced with projects far more damaging than those recently approved. Cheaper, more effective, and more environmentally friendly alternatives need the support and momentum the Green Climate Fund can provide. Both solar and wind power, for example, have proved to be more efficient and less costly than large-scale hydropower. Other less-developed technologies, such as geothermal, have largely unexplored potential. As part of a coalition of civil society organizations monitoring the Fund’s decisions, AIDA will continue working to ensure that the recent decision to fund large dams does not become a precedent.

Read more

In search of legal protection for Mexico’s reefs

From the coasts of Baja California to the shallows of the Caribbean, Mexico is home to an incredible array of reefs. The coral and rocky reefs found throughout the country are sources of food and potentially life-saving genetic material. They protect people on the coasts from the impacts of storms and hurricanes, stimulate tourism, and provide shelter for a wide variety of plants and animals. Despite their inherent value, Mexico does not yet have an overarching law for reef protection. This vital task is instead governed by a variety of legislation and by international treaties that establish the country’s obligations to preserve these valuable ecosystems. Climate change is one of the most serious threats to reefs. Oceans are becoming warmer and more acidic, conditions that reduce reefs’ capacity to grow and repair themselves. In addition, warmer water disperses the algae that corals feed on, leaving the corals weakened and at risk of death. This month, the Mexican Senate’s Special Climate Change Commission decided to do something about the threats facing corals. They convened a series of meetings to promote the creation of a legislative instrument aimed exclusively at protecting the nation’s many reefs. I participated in these meetings as a representative of AIDA, alongside our colleagues from Wildcoast and scientists, academics, and community members who benefit from the services reefs provide. We drew the Senate’s attention to the serious threats facing reefs, and to the urgency of applying the precautionary principle to guarantee the human right to a healthy environment, which is at risk due to the lack of adequate regulations for reef conservation. To guarantee this right and to protect the oceans against climate change, Mexico has signed international treaties including the American Convention on Human Rights, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, and the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles. The Veracruz Reef, an emblematic case Reefs around the country are also being threatened by inadequately planned coastal infrastructure and insufficient environmental impact assessments. This is the case with the expansion of the port of Veracruz, a project that endangers the Veracruz Reef System, the largest coral ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico. The site was declared a Natural Protected Area in 1992, a priority region for the National Commission for the Knowledge and use of Biodiversity in 2000, a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 2006, and a Ramsar site. Even so, the government reduced the size of that area in 2013 to make way for the port project, violating international conventions such as the Ramsar Convention, under which the Veracruz reef is recognized as a Wetland of International Importance. Learn more about the case in the following video: Hope for Mexico's Marine Heritage We are confident that the Senate initiative will bear fruit and that Mexico will develop a law for the protection of its reefs, and that it will be born from a transparent and participatory process to which we will continue to contribute. To learn more about the topic, see our report The Protection of Coral Reefs in Mexico: Rescuing Marine Biodiversity and its Benefits for Humanity.

Read more

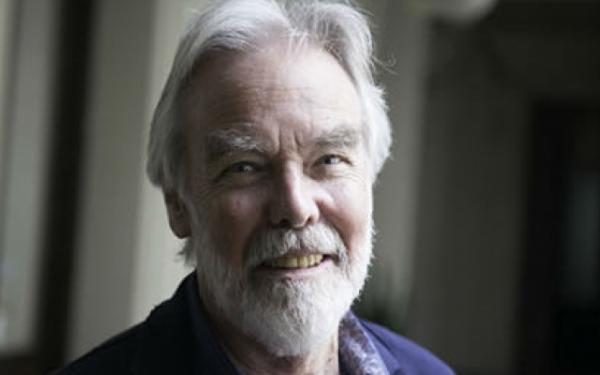

Remembering Robert Moran

It is with great sadness that we share news about the passing of Dr. Robert E. Moran, a distinguished hydrogeologist who was an immense resource in furthering environmental protection globally and a dedicated partner to AIDA. He died May 15 in a car accident while vacationing in Ireland. With over 45 years of experience in water quality monitoring, geochemical, and hydrological work, Dr. Moran was invaluable in the fight for clean water and responsible mining worldwide. His work as an expert on the environmental impacts of mining led him to collaborate with a wide range of actors, from non-governmental organizations and indigenous communities, to private sector and government clients. He was an admirable scientist and a strong defender of environmental rights. Some of Dr. Moran's recent projects in Latin America included: a review of technical issues at the Veladero gold mine in Argentina following a toxic cyanide spill; providing assistance and training to Colombian government officials on coal mine inspection and water quality monitoring; and preparing reports evaluating the environmental impact statements of the Minero Progreso Derivada II project in La Puya, Guatemala. Dr. Moran also conducted reviews of mining operations and their impacts in Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Honduras, as well as in Africa, Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and the United States. He dedicated his life to helping others understand and better evaluate the true costs of mining activities. Dr. Moran will be sorely missed by many in the environmental movement and people everywhere whom his life touched. We honor and thank him for all of his magnificent work to defend our planet.

Read more