Project

Photo: UNFCCCMonitoring the UN Climate Negotiations

As changes in climate become more extreme, their affects are being hardest felt throughout developing countries. Since 1994, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change has laid out actions to limit the increase of global average temperatures and confront the impacts of climate change.

The States that are Parties to the Convention meet every year in the so-called Conference of the Parties (COP) to review their commitments, the progress made in fulfilling them, and pending challenges in the global fight against the climate crisis.

At COP21 in 2015, they adopted the Paris Agreement, which seeks to strengthen the global response to the climate emergency, establishing a common framework for all countries to work on the basis of their capacities and through the presentation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) that will:

- Limit the increase in global temperatures to 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels and continue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C;

- Increase the capacity of countries to adapt to the impacts of climate change; and

- Ensure that financing responds to the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Our focus areas

THE CLIMATE CRISIS AND HUMAN RIGHTS

The climate crisis, due to its transversal character, has repercussions in various fields, geographies, contexts and people. In this regard, the Preamble to the Paris Agreement states that it is the obligation of States to "respect, promote and fulfill their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, the empowerment of women and intergenerational equity."

AIDA at the COP

COP25: Chile-Madrid 2019

At COP25 in Madrid, Spain, we advocated for the inclusion of the human rights perspective in various agenda items. We promoted the incorporation of broad socio-environmental safeguards in the regulation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which refers to carbon markets. We closely followed the adoption of the Gender Action Plan, as well as the Santiago Network, created "to catalyze technical assistance […] in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse affects of climate change." We also encouraged the inclusion of ambitious and measurable targets for the reduction of short-lived climate pollutants in the climate commitments of States.

Related projects

Latest News

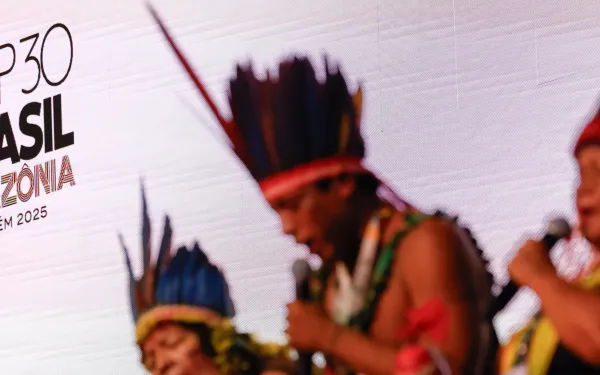

COP30 ends — with a few achievements to move forward

With more than 25 hours of delay, the 30th UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) has come to an end. The so-called "Amazon COP," held in the Brazilian city of Belém do Pará, leaves behind disappointment for failing to change course, but also some advances that can help push climate action forward. It was not a total failure: multilateralism remains intact, though battered.COP30 was marked by the presence of Indigenous peoples, especially from the Amazon basin, who filled the streets and side events. However, according to reports, only a fraction of these delegations gained access to the formal negotiation rooms, while a disproportionate number of representatives from the fossil fuel industry participated in the official event. This imbalance reflects the democratic health of the climate regime: at the Amazon COP, the power of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples was felt in the streets, but their voices remained underrepresented in decision-making spaces.A few days into the conference, the latest synthesis report of updated nationally determined contributions was released. Its message was more bitter than sweet, but it offered one important takeaway: although the gap to keep global warming below 1.5°C remains enormous and complex, the report confirms that the Paris Agreement has indeed helped steer the challenge. We are in a better position than in a scenario without the agreement: projected emissions growth has been slowed, though not nearly enough.At this point, it is clear that COPs will not "save the world," but it also seems impossible to overcome this crisis without the cooperative platform they provide. From that perspective, it is worth asking what COP30 leaves us. The approved agreement: Global MutirãoThe word "Mutirão" references the spirit of collective effort—body and soul—that Brazil sought to bring to the international negotiation process at this COP.The approved agreement reiterates the goal of keeping the planet’s temperature increase below 1.5°C, acknowledging that time is running out. To that end, it proposes two voluntary mechanisms, led by the Presidency, which for now seem more like statements of good intent than tools with teeth: a "Global Implementation Accelerator" and the "Belém Mission for 1.5°C."On financing, the text establishes a two-year work program on Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which concerns the public resources developed countries must provide, understood in the context of Article 9 as a whole.A footnote was added to clarify that this does not prejudge the implementation of the new global goal. Civil society organizations warn that this formulation risks further diluting developed countries’ specific obligations under the narrative of "all sources of financing," without clear rules on who must actually provide the resources and under what conditions. The real value of all this remains to be seen in practice. What was gained: A new mechanism for a just transitionA major achievement of COP30 was the adoption of the Belém Action Mechanism (BAM), a new institutional arrangement under the Just Transition Work Programme. It was the main banner carried by organized civil society.The mechanism is designed as a hub to centralize and coordinate just transition initiatives around the world, providing technical assistance and international cooperation to ensure the transition does not repeat the mistakes of the fossil era.The text incorporates many of the principles championed by Latin American civil society—including human rights, environmental and labor protections, free, prior and informed consent, and the inclusion of marginalized groups—as essential elements for achieving ambitious climate action.Even with gaps in safeguards and governance definitions, the BAM is a concrete step forward for this COP on climate justice. It creates a starting point to discuss not only whether there will be a transition, but how it will be done and under what rules, so as not to replicate the logic of the fossil economy. Its design and implementation will be debated at upcoming COPs, where it will be crucial for the region to arrive with solid, united proposals. Ending fossil fuels and deforestation: Two “almosts” that move us forwardAn agreement to leave behind fossil fuels and end deforestation—directly addressing the main drivers of the climate crisis—"almost" made it into the final decision.More than 80 countries from both the global north and south called for a roadmap to exit oil, gas, and coal. More than 90 supported a roadmap to stop and reverse deforestation by 2030. Although these requests made their way into drafts of the closing decision, they disappeared from the final text after resistance from major fossil fuel producers.Still, we do not leave empty-handed: Brazil, as COP30 Presidency, announced it will advance these roadmaps outside the formal framework of the UNFCCC. For the fossil fuel phaseout, Colombia committed to co-organize, with the Netherlands, the first global conference on the topic in April 2026.Although these items were not secured within the official negotiations, it is worth celebrating that—for the first time—such a broad coalition of countries united to achieve them. These two "almosts" matter: they set a new political and legal baseline for the rounds ahead. Two tools to advance adaptationCOP30 delivered tools to keep adaptation negotiations moving forward.The Mutirão decision calls for tripling collective adaptation finance by 2035, tied to the $300 billion USD per year agreed under the new global goal. This falls short of what the poorest countries asked for (tripling by 2030, with an explicit figure) and lacks clarity or guarantees regarding the role of developed countries. But it is a political anchor worth building on.At the same time, a first package of 59 indicators was adopted for the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). Several African countries and experts described them as "unclear, impossible to measure, and in many cases unusable," because they sacrifice precision and grounding in community realities in order to unblock the agreement. In response, the text included the "Belém–Addis Vision," a two-year window to correct flaws and make the framework operational by 2027.In short, we have more promises of money and an indicator framework weaker than necessary, but also a process through which the region can continue pushing for a useful GGA and for fair, sufficient adaptation finance. Loss and damage: Slow and uncertainProgress on this issue has been painfully slow compared with the urgency of the problem. At COP30, the third review of the Warsaw International Mechanism was finally approved. The result is frustrating: discussions have taken a decade while communities are already paying the cost of warming.On the other hand, the Loss and Damage Response Fund, created two years ago, issued its first call for proposals, with an initial package of $250 million USD in grants available over the next six months. The Fund has $790 million USD pledged, but only $397 million USD actually deposited—an enormous gap compared to the hundreds of billions estimated annually for developing countries.The expected political pressure for developed countries to scale up contributions was largely diluted in the final text, although the Fund was at least linked to the new global financing goal agreed at COP29. A new Gender Action PlanCOP30 concluded with the adoption of a new Gender Action Plan under the renewed Lima Work Programme. The Plan identifies five priority areas: capacity-building and knowledge; women’s participation and leadership; coherence among processes; gender-responsive implementation and means of implementation; and monitoring and reporting. It also provides a roadmap to ensure climate action is truly gender-responsive, with indicators to track progress. Methane: A super-pollutant still lacking the spotlight science demandsAt COP30, short-lived climate pollutants—especially methane—gained visibility thanks to a dedicated pavilion and dialogues with regional and global actors. The Global Methane Status Report 2025 was also presented, noting “significant” progress since the 2021 launch of the Global Methane Pledge. However, it warns that current progress remains far from the goal of reducing methane emissions by 30% by 2030.In the official negotiations, the draft of the Sharm el-Sheikh Mitigation Ambition and Implementation Work Programme included an explicit reference to methane mitigation through proper waste management, but that mention was removed from the final text, leaving only a general call to improve waste management and diminishing the focus on the urgent need to reduce emissions of a pollutant whose mitigation is essential to achieving the Paris Agreement goals. Still, during COP30, the global “No Organic Waste (NOW) Plan to Accelerate Solutions” was launched, aiming to reduce methane emissions from organic waste by 30% by 2030.Overall, this COP missed a crucial opportunity to advance its core objective. If we truly want to stay on track with the Paris Agreement, we must treat methane as what it is: a decisive opportunity we are still not seizing. How we close COP30 and prepare for the nextCOP31 will be held in Turkey, under the presidency of Australia. And despite the shortcomings of COP30, there are at least four things to defend and build on:The normalization of the debate on phasing out fossil fuels, with more than 80 countries openly calling for a roadmap and Colombia–Netherlands taking that discussion to a dedicated conference in 2026.A forest agenda that, although left out of the text, carries the promise of a Brazilian roadmap and explicit support from a wide group of countries.A small but real advance on adaptation, with the decision to triple finance and a first set of indicators that, while weak, offer a basis to push for improvements.The creation of a new mechanism for a just transition, which can shape how the transition unfolds—bringing together and strengthening efforts that support and protect workers, communities, and Indigenous peoples.

Read more

The home stretch of COP30: Shadows, contradictions, and some glimmers of hope

The first week is over, and the political phase of the 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) has begun in Belém do Pará, Brazil. These are the days when decisions must be made.A COP had not been held in a country where public protest is possible since 2021 — and people have certainly made their voices heard. On Saturday, a massive demonstration took place: thousands demanded climate justice in the streets, to the rhythm of Amazonian drums. There was also a theatrical "funeral for fossil fuels," reminiscent of Tim Burton, with monsters and somber widows bidding farewell to an era that must be buried.But it has not all been carnival. Indigenous leaders blocked access to the event several times and even entered the "blue zone" — the restricted area — en masse, denouncing the exploitation of their territories. Their discontent is absolute. Although COP authorities met with the group, they soon sent a letter to the Brazilian government requesting increased security and the dispersal of protests. Human rights and environmental organizations have warned about the risks of criminalizing protest and the harmful message this sends about the role of Indigenous peoples.These protests reflect communities that ended up being a minority in an event that promised to be inclusive. There was also widespread criticism of the disproportionately large number of fossil fuel industry representatives involved in negotiations — a dynamic that makes the path toward climate justice even more complicated.Finally, advisory opinions (AOs) must not be left out of this review. While not formally on the agenda, they have made a strong impact. Their central message is powerful: international cooperation is not optional — it is a legal obligation. It is no surprise, then, that the theme keeps resurfacing: in side events, in constant references by civil society and some national delegations, and in cross-cutting mentions across debates on finance, adaptation, and transition. The AOs are not merely being cited; they are being embraced. Momentum is building to fully unleash their potential at this COP and beyond. Negotiations: Four key issues in “presidential consultations”The COP Presidency acted quickly with a novel approach: to adopt the agenda without delays, it set aside four complex issues and moved them into “presidential consultations.”Article 9.1 — Public Funding from Developed Countries. The debate centers on whether climate financing should come only from public sources or also from private sources, as well as on accountability and reporting standards. Developed nations — which are legally obligated to provide this financing — are resisting, while vulnerable countries urgently need the funds to survive the climate crisis.Unilateral Climate-Related Trade Measures. These include policies such as carbon border taxes. They are considered unfair or protectionist, especially by Global South countries with less capacity to reduce emissions. Negotiations aim to prevent arbitrary trade barriers while respecting climate action.NDCs and Ambition. According to the latest NDC synthesis report, there is a significant gap between current commitments and what is required to stay below 1.5°C. Many negotiators argue that agreeing on concrete measures to close that gap is essential, but large emitters continue to resist.Synthesis of Climate Transparency Reports. Under the Paris Agreement’s Enhanced Transparency Framework, countries must periodically report emissions, actions taken, and financial support provided or received. At COP30, the debate centers on how to make these synthesis reports more robust, comprehensive, and useful. The consultations have been tense and slow. On Sunday, the Presidency published a "summary note" outlining possible pathways, and today a draft decision was released, though reactions are still forthcoming. In the coming days, closed-door sessions will continue and could lead to various outcomes. Based on the draft, it seems increasingly likely that COP30 will end with a “cover decision” consolidating all progress and addressing these complex matters. The final scope will depend heavily on what happens during the next four days. A just energy transition: Promises and a mechanism that worksThe Belém Action Mechanism for a Just Transition is a new institutional arrangement under the UNFCCC, championed by NGOs and Global South countries. Its objective is to bring order to the currently fragmented landscape of just transition efforts. The mechanism would coordinate initiatives, systematize knowledge, and provide quality financing and support — essentially evolving the Just Transition Work Program discussed since COP27.Civil society, particularly the Climate Action Network (CAN), has invested enormous effort in developing a strong decision that advances the creation of this mechanism. The G77 + China — the largest negotiating bloc of developing countries — supported this proposal, earning CAN’s "Ray of Light" award, given to actors making significant contributions to climate justice.Some developed countries presented less ambitious proposals, but even that confirms that convergence is drawing closer. Civil society remains optimistic that a concrete, positive outcome will be achieved — and ready to celebrate it. A path to phase out fossil fuelsThis story began in 2023 at COP28 in Dubai, when, for the first time, the idea of phasing out fossil fuels appeared in an official COP text.Now, at the opening of COP30, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva explicitly referenced a "route" for the energy transition, while Environment Minister Marina Silva has worked to reinforce the political momentum. Meanwhile, Colombia issued a declaration referencing the advisory opinions and seeking international support for the initiative. Several industrialized countries have revived their position through the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance.Today, 63 countries support a commitment to "Transition Away from Fossil Fuels." However, this is not yet part of the formal negotiation agenda — initiatives remain fragmented, and efforts proceed in parallel. What could emerge is a concrete action plan, a dedicated section in the final decision, or perhaps a roadmap for a future roadmap. The alternative is that it remains a voluntary coalition of willing countries pushing the idea forward. Climate finance: The central — and most complicated — issueFinance remains the central issue at this COP, and perhaps the most complex. Several deeply interconnected discussions are underway:Article 9.1: Developing countries insist that public financing from developed nations is a binding obligation that cannot be replaced by private investment.Adaptation: A strong consensus is forming to triple the adaptation finance goal (to about USD 120 billion annually) while improving transparency and direct access to funds.The Baku–Belém Roadmap: This initiative seeks to scale up global climate finance to USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035 through a combination of public, multilateral, and private flows.Loss and Damage Facility: The fund is technically operational but not fully capitalized. New contributions from Spain and Germany are welcome — but insufficient to meet global needs.Tropical Forests Forever Facility: Brazil has proposed this as an “investment model” for tropical forest countries. Civil society has expressed serious concerns: the model depends heavily on volatile market investments and lacks safeguards to ensure the protection of local communities and ecosystem integrity. Adaptation progress, but under the shadow of chronic underfundingDiscussions on adaptation are unfolding on two parallel fronts:Indicators for the Global Goal on Adaptation. Ten years after the Paris Agreement, there is still no consensus on how to track adaptation progress. A working group narrowed approximately 9,000 proposed indicators down to about 100, but technical and political challenges persist. Some African and Arab countries have asked to postpone final adoption until they have the financial resources and capacity to implement them. A prevailing sentiment is: "no indicators without funding" — adopting metrics without support would repeat past mistakes.Adaptation finance. Although adaptation financing is not formally included within the Global Goal on Adaptation, the two issues are inseparable. Without adequate financial support, indicators alone will be ineffective. Following the agreement on a new climate finance goal at COP29, the current debate focuses on aligning that goal with adaptation needs — especially through technology transfer, capacity building, and direct-access funding channels. Substantial gaps remain, and negotiations continue to hinge on how to categorize financial flows (private vs. public, domestic vs. international).

Read more

The Ocean-Climate Link: 5 Things to Know

Por Víctor Quintanilla y Natalia Oviedo*Although the ocean is essential for stabilizing the planet's climate, it is rarely the focus of attention when we talk about the global climate crisis.The ocean is our best ally in the face of the climate emergency because it absorbs much of the greenhouse gases that humanity emits and that are the source of the problem.At the same time, the ocean is a victim of the climate crisis, whose impacts are pushing it to the limit with acidification of its waters, rising sea levels, and loss of oxygen, processes that seriously affect marine life.Despite its importance, the relationship between the ocean and climate has not been fully included in international negotiations in which governments seek agreements and policies to address the climate crisis.Faced with this gap and in a historic breakthrough, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea issued a ruling in 2024 clarifying the obligations of States to protect the marine environment from the climate crisis.Below, we present five keys to understanding the link between the ocean and climate.1. The role of the ocean in the climate crisis.According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the ocean is “a fundamental climate regulator on timescales ranging from seasonal to millennial.” Since 1955, it has absorbed 90 percent of the excess heat caused by global warming, along with a quarter of the carbon dioxide released by human activities.Ocean currents transport warm water from the tropics to the poles, sending colder water back. This balances the temperature and makes much of the Earth habitable. The ocean influences climate variations on land by being the main source of rain, which feeds rivers and other vital freshwater systems.The ocean is known as a lung for the planet because, through microscopic organisms known as phytoplankton, it is responsible for generating approximately half of the world's oxygen supply. In turn, coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, marshes, and seagrass beds absorb enormous amounts of carbon from the atmosphere, mitigating the climate crisis. 2. The impact of the climate crisis on the ocean.The climate crisis alters the physical and chemical properties of the ocean, affecting its ability to regulate the climate. One of the irreversible impacts of climate change is ocean warming, whose rate and heat absorption has more than doubled since 1993. As its waters warm, they begin to release carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere.In addition, rising ocean temperatures are expected to reduce the amount of oxygen available, altering nutrient cycles and thereby affecting fish distribution and abundance. Another consequence is sea level rise, which is due to thermal expansion of the ocean and loss of land ice.Finally, the absorption of increasing amounts of carbon dioxide has resulted in ocean acidification, understood as a decrease in pH. This reduces calcium levels, a substance necessary for the shells and external skeletons of various species of marine fauna and ecosystems such as coral reefs.3. The inclusion of the ocean in international climate negotiations.Although the link between the ocean and climate change has been recognized since the beginning of negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—by including the ocean in the definition of “climate system”—its presence in these negotiations has been gradual. A decisive milestone occurred at the 25th UN Climate Change Conference (COP25) in 2019, where the first official dialogue on the subject was called for, resulting in recommendations to align climate and ocean action, while also promoting the mobilization of financing to protect marine ecosystems. Since then, the ocean has earned a permanent place on the climate agenda. At subsequent conferences, the inclusion of the ocean was further expanded. The Glasgow Climate Pact (COP26, 2021) recognized the ocean as an ally in carbon absorption, called for the integration of ocean-based action into UNFCCC work plans, and mandated an annual dialogue on the topic. At COP27 (2022), countries were encouraged to include ocean-based action in their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). And at COP28 (2023), the ocean was included in the first global stocktake of the Paris Agreement.Ahead of this year's COP30 in Brazil, which will have a specific agenda on “Forests, Oceans, and Biodiversity,” the challenge is to move from political recognition to the implementation of concrete actions to protect the ocean.4. States' obligations to protect the ocean in the face of the climate crisis.The health and resilience of the ocean is essential not only for addressing the climate crisis, but also for the exercise of fundamental human rights such as life, health, culture, food, access to water, and the right to a healthy environment. This highlights the interdependence between the ocean, climate change, and human rights.Recognizing this link, on May 21, 2024, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea issued an important decision clarifying the obligations of States to preserve the ocean in the face of the climate crisis. These duties include adopting concrete mitigation measures to minimize the release of toxic substances into the marine environment, as well as exercising strict due diligence to ensure that non-state actors effectively comply with such measures.The tribunal emphasized the obligations of states to prevent climate change-related pollution that affects other states and the marine environment outside national jurisdiction. In relation to the right to a healthy environment, the ruling emphasizes the use of precautionary and ecosystem approaches in the context of states' obligations to conduct environmental and socioeconomic impact assessments of any activity that may cause marine pollution related to climate change. This includes that, in the face of the possibility of serious or irreversible damage to the marine environment, the lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as an excuse to delay protective measures.5. Some key actions to protect our ocean and, with it, the climate.Effective protection of our ocean requires the commitment of governments, which must act at the national and international levels to prioritize its health. These include:Prioritizing concrete measures that integrate the ocean into climate mitigation and adaptation actions. Among the most effective are the protection and restoration of ecosystems, especially those that, in addition to capturing and storing enormous amounts of carbon, protect coastlines and maintain vital ecosystem services (mangroves, marshes, seagrass beds, coastal wetlands, and coral reefs, among others).Ensuring the protection and sustainable use of biodiversity in the ocean area beyond national jurisdiction. This involves the effective implementation of the High Seas Treaty, which will enter into force on January 17, 2026, as well as its ratification by countries that have not yet done so, to ensure fair, equitable, and sustainable governance.Defending the deep sea from mining. This requires imposing moratoriums on deep-sea mining activities on the grounds that there is insufficient technical and scientific information to prevent, control, and mitigate the potential impacts on the biological diversity of unknown ecosystems in deep waters and on the seabed.Protect the rights of coastal and island communities, which depend on fishing and local tourism for their livelihoods. These populations face increasing impacts from the climate crisis and multiple environmental pressures. Governments have a responsibility to ensure their resilience and well-being by safeguarding the marine and coastal biodiversity that sustains their ways of life and culture.Acknowledging the link between the ocean and climate, and translating it into concrete and effective measures, is essential to protect and maintain the balance of both life systems.This is what will guarantee the health of marine and coastal biodiversity, our food security, and, ultimately, a future for the planet.* Víctor Quintanilla is AIDA's Content Coordinator; Natalia Oviedo is a Costa Rican international lawyer and former intern at the organization.

Read more