Press Center

Organizations request that the IACHR strengthen State obligations to supervise corporate activities that violate human rights

In a hearing before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, they highlighted the opportunities that the Commission has to address the problem through the creation, implementation and strengthening of international standards on business and human rights. Washington D.C. In a hearing before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, civil society organizations requested that the Commission provide renewed attention to the problem, increasingly experienced in the hemisphere, of human rights violations committed by corporations. The hearing was jointly requested by the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), a regional organization; the Association for Human Rights (APRODEH) of Peru; the Center for Human Rights and Environment (CEDHA) of Argentina; and Justiça Global of Brazil. The organizations applauded the Commission’s openness to directly addressing, for the first time, the theme of business and human rights in a public hearing. “Through various mechanisms in recent years, the Commission has received a large amount of information about cases of human rights violations in which corporations have played a central role, but the problem has worsened because of a lack of effective solutions. In this sense, one of the biggest challenges the Commission has is to find ways to address the issue properly and to help both the States and the corporations to fulfill their human rights obligations,” explained Astrid Puentes, co-executive director of AIDA. Through their work, the organizations have seen that most recurrent aspects of the problem include: the impacts of megaprojects and extractive industries on human rights and the environment; difficulties in guaranteeing the right to participation and access to information for affected people and communities; the absence of Human Rights Impact Assessments; systematic violations of labor rights and forced labor practices; the privatization of public security forces to protect business activities; and aggression towards and criminalization of people who defend the environment, their territory and human rights. At the hearing, the organizations reminded that progress has been made in the development international standards on business and human rights. One such example, they explained, is the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. "However, because compliance is voluntary and there are various legal loopholes, this instrument has not been effective enough to prevent the continuation of human rights abuses. Also, effective regulation of territorial and extraterritorial State obligations regarding the responsibilities of transnational corporations on national, regional and international levels does not exist. This sort of vacuum prevents both the safeguarding of people’s rights, and access to appropriate compensation and justice for victims,” said Alexandra Montgomery of Justiça Global. Looking forward, the organizations presented information about the opportunities the Commission has to strengthen the implementation of existing standards. They emphasized the following points: The Commission should promote corporations’ respect for human rights. This includes promoting State responsibility for adequate supervision of business activities and for establishment of binding obligations for them, since the voluntary nature of the Guiding Principles compromises and puts at risk the protection of human rights. Based on the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Human Rights System in relation to the obligations of States to respect and guarantee human rights, the Commission can develop specific measures for States to supervise business activities to ensure that they do not violate human rights. Respect for human rights by States and companies must not be subject to economic or political considerations. It is necessary to strengthen access to justice for victims of human rights abuses by business actors through recommendations for improvement and implementation of accountability mechanisms and international forums, such as the Commission and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. “We hope that as a result of the hearing, the Commission initiates dialogues that incorporate the experience of civil society organizations and of United Nations agencies to strengthen the respect of and guarantees for human rights in the region,” concluded Gloria Cano, of APRODEH.

Read moreGeneva Conference must give clarity to climate finance

Negotiations for a new climate agreement, initiated last December during the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 20) in Lima, Peru, will continue this week in Geneva, Switzerland. Delegates there will work on detailing the various elements to be included in the negotiating text of the new climate agreement, including climate finance. Climate finance is a key factor in enabling developing countries to confront climate change effectively. "We hope the Geneva session concludes with a negotiating text that provides clarity for predictable and sustainable financing," said Andrea Rodriguez, attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). "The agreement needs to establish with certainty the sources of finance, which institutions will mobilize and manage them, and how they will be disbursed, in order to ensure that these efforts contribute to low-emission, climate-resilient development in developing countries." The Conference in Peru ended with the Lima Call for Climate Action, a document whose annexes contain the essential elements for a draft negotiating text of the new climate agreement, which will be signed later this year at COP 21 in Paris. Delegates in Geneva are expected to intensify work on those key elements, and produce a negotiating text that will have legal force under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Given the importance of the Geneva conference, AIDA is providing climate finance recommendations for negotiators to incorporate into the draft text of the new climate agreement: Clear provisions regarding who is required to mobilize resources. Clear goals beyond 2020 for a road map towards annual public financing targets. Scaling up of resources to ensure compliance with the existing commitment to mobilize $100 million by 2020, and to allow countries to plan their climate actions. Predictable, adequate and sufficient climate finance to promote the transition to low-carbon, climate-resilient development in developing countries. 50:50 balanced allocation of resources for adaptation and mitigation actions. Definitions of climate finance and climate investment. Clarity on which climate finance institutions will operate under the convention. Recognition of the Green Climate Fund as the primary channel to mobilize resources, without the exclusion of other funds. Strengthen the mandate of the Standing Committee of Finance to enhance coordination and coherence of work between different financial institutions.

Read more

UN registered Barro Blanco Hydroelectric Dam temporarily suspended over non-compliance with Environmental Impact Assessment

Panama City, Panama and Geneva, Switzerland. In a landmark decision, Panama’s National Environmental Authority (ANAM) temporarily suspended the construction of the Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam yesterday over non-compliance with its Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). The dam was approved by the UN Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) despite risks of flooding to the territory of the indigenous Ngäbe Bugle communities. With delegates currently meeting in Geneva to draft negotiating text for a new global climate agreement, ANAM’s decision illustrates why the agreement must include human rights protections, including the rights of indigenous peoples. In Geneva, several nations have already insisted on the need for climate measures to respect, protect, promote, and fulfil human rights for all. "Panama has taken a critical first step toward protecting the rights of the Ngäbe communities, which have not been adequately consulted on the Barro Blanco CDM project. But much more work is needed," said Alyssa Johl, Senior Attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). "As an urgent matter, Panama should recognize its obligations to protect human rights in climate actions, such as Barro Blanco, by supporting the call for human rights protections in the UN climate regime." Current climate mechanisms, such as the UN’s Clean Development Mechanism, neither provide incentives for the sustainable implementation of climate actions nor offer recourse in the case of adverse impacts. "The CDM Board approved Barro Blanco when it was clear that the dam would flood the homes of numerous indigenous families. This decision is a warning signal that safeguards must be introduced to protect human rights, including robust stakeholder consultations and a grievance mechanism," said Eva Filzmoser, Director of Carbon Market Watch. ANAM’s decision was triggered by an administrative investigation that found non-compliance with the project’s environmental impact assessment, including shortcomings in the agreements with affected indigenous communities, deficiencies in negotiation processes, the absence of an archaeological management plan for the protection of petroglyphs and other archaeological findings, repeated failures to manage sedimentation and erosion, poor management of solid and hazardous waste, and logging without permission. The Environmental Advocacy Center of Panamá (CIAM) considers it appropriate for ANAM to have taken effective and immediate measures to suspend the project. "This suspension reflects inadequate environmental management on the part of the company that requires an investigation and an exemplary sanction". "During 15 years of opposition to the Barro Blanco project, we have exposed violations of our human rights and irregularities in the environmental proceedings. Those claims were never heard," said Weni Bagama from the Movimiento 10 de Abril (M-10). "Today we are satisfied to see that the national authorities have recognized them and have suspended the project, as a first step towards dialogue. Nevertheless, we continue to uphold the communities’ position that the cancelation of this project is the only way to protect our human rights and our territory. We hope that this sets an example for the international community and for other hydroelectric projects, not only in Panama but worldwide." "Any dialogue between the affected communities, the Government and the company has to be transparent, in good faith, respectful of the communities’ rights, and include guarantees so that the communities can participate equally and the agreements are fully respected," explained María José Veramendi Villa, Senior Attorney at the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). "In this dialogue, the State must take into account all human rights violations that have been denounced by the communities since the project was approved." Environmental groups around the world are celebrating the suspension of the Barro Blanco Dam, following years of efforts in support of the indigenous populations in the Ngäbe Bugle comarca, which have been faced with oppression and numerous rights violations. Eyes are now watching for the reactions of the banks involved in financing the Barro Blanco project, including the German development bank, DEG, and the Dutch development bank, FMO, against whom the M10 movement, which represents the indigenous communities, had filed a complaint. "We urge the banks to halt disbursement of any remaining funds until all problems are solved and the affected indigenous communities agree to the project," said Kathrin Petz of Urgewald.

Read more

New law protects Panama Bay Wetland Wildlife Refuge

On the occasion of World Wetlands Day, the President of Panama will approve a national law that bestows protected-area status on Panama Bay Wetland Wildlife Refuge. CIAM and AIDA applaud the decision to strengthen protection of an ecosystem key to biodiversity, freshwater supplies, and the fight against climate change. Panama City, Panama. In an official ceremony on World Wetlands Day, President Juan Carlos Varela will approve a law that bestows protected-area status on Panama Bay Wetland Wildlife Refuge, which was initially established by Administrative Resolution. The government is strengthening legal protection of an ecosystem key to fresh water supplies, reproduction of species of high commercial and nutritional value, biodiversity conservation, and climate change mitigation. "We welcome a law that demonstrates the importance that this place has on the environment and surrounding populations. It is everyone’s responsibility to protect the 85,652 hectares of coastal marine wetlands in Panama Bay," said Brooke Alfaro, President of the Board of the Environmental Advocacy Center (CIAM). The Bay is one of the world’s most important nesting and resting sites for migratory birds and a home to endangered species. Mangroves help to fight climate change by capturing carbon from the atmosphere, and mitigate its effects by serving as a buffer against coastal storms and hurricanes. In 2003, it was declared a site of international importance under the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty for the conservation of wetlands. "We congratulate the Panamanian government because this law is a breakthrough for wetland protection and for fulfillment of the country’s international obligations. It serves as an example for other countries in the region. The law emphasizes the concepts of rational use, ecosystem approach, and ecological character contained in the Ramsar Convention," said Haydée Rodríguez, attorney for the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). During the law’s approval process, CIAM’s legal and scientific team, supported by AIDA, helped strengthen the bill to ensure that it guarantees sound management of wetland resources. Both organizations will assist and support the Government of Panama in implementing the law. "We must establish an appropriate management plan to ensure the protection of the wetland for present and future generations," added Rodríguez. "Thanks to the support of citizens, civil society, the Supreme Court, deputies and government, the law ensures protection of the Panama Bay Wetland," Alfaro said. In recent years, the site has been affected by the expansion of real estate projects, with consequent channeling of rivers, drainage, and filling of natural areas. Under the new law, activities that threaten the ecological integrity of the refuge and of its boundaries are prohibited. Only another law may permit them.

Read moreOrganizations asked that the IACHR urge the Colombian State to comply with international obligations, to declare a moratorium on mining and energy projects, and establish a Working Group between authorities and the affected communities

They also asked that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) urge the State to adequately attend to the victims of the forced displacement caused by the “development” projects, and to begin a dialogue between the victims and the authorities seeking effective solutions to the problem. Washington, D.C., USA – In a hearing last Monday before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), in its 153rd Period of Sessions, organizations and social movements requested that the international body urge the Colombian State to recognize that forced displacement caused by the implementation of "development" projects is a human rights violation that must be prevented. They also asked that the Commission verify this grave situation with a visit to the affected areas. The organizations expressed their deep concern for the dangerous situation in which people and communities are placed as they defend their land and their environment. The resistance to megaprojects has resulted in the murder of 13 people, the disappearance of one, and threats against 25 people who defend the country’s rivers. The violence has included the recent assassination of a Nasa indigenous community leader, opposed to the Colosa mine, and a serious threat against the indigenous governor of Córdoba. The participants presented concrete cases in which the megaprojects have destroyed territories, ecosystems and ancient cultures, causing irreparable damage and leading to the forced displacement of populations. The participants presented before the IACHR three main factors that have been driving the forced displacement: 1.The close relationship between the armed conflict and the implementation of megaprojects; 2. The deregulation and violation of laws in the authorization and implementation of projects; and 3. The direct impacts from the implementation of the megaprojects. They pointed out that sociopolitical violence has enabled the implementation of mining and hydroelectric projects, causing the exodus of people from their lands and the appropriation of those lands by corporations. "The paramilitary leader Salvatore Mancuso recognized that three-thousand people from the region of Córdoba were displaced to make way for the megaprojects, because the companies needed the land for the construction of dams," the participants stated. They also indicated that the implementation of megaprojects in Colombia precludes the processes of truth, justice, and reparation, let alone any guarantees to the victims of armed conflict and development that these wrongs will not be repeated. Additionally, the participants pointed out that the State is making arbitrary use of legal instruments, such as the declaration of public utility, to clear the way for these projects, without considering their impact on human rights and the environment. The State is championing the principle of public interest, which, in practice, has been converted into a mechanism for expropriation or legal dispossession, and, as a consequence, has been the cause of the displacement. The megaprojects are having a grave impact on the ancient territories and cultures, causing irreparable damage, such as environmental contamination, that is resulting in the forced displacement of entire populations. These causes, which have created at least 200,000 victims of forced displacement, are the basis of the organizations’ request that a moratorium on mining and hydroelectric projects be instituted in Colombia as the only guarantee for the protection of further human rights violations until the policy is structurally evaluated and fundamental rights are guaranteed to those affected populations. Finally, the organizations asked for the intervention of the IACHR so that the Colombian State immediately establishes an Integrated Working Group, where the victims may participate in a discussion about mining and energy policy and have a voice in the development of a responsive business model that meets the needs of the affected communities. In this discussion, the State would also be urged to take note of the warnings issued by the Constitutional Court and the Comptroller General of the Republic regarding the need to identify alternative sources of energy, as stipulated by the World Commission on Dams.

Read moreOrganizations alert World Bank to risks of Colombian mining investment

Delegation explains to the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a branch of the World Bank Group, illegalities and possible harms to people and the environment from Eco Oro Mineral’s Angostura mine in Santurbán, Colombia. Washington/Ottawa/Bogota/Bucaramanga. From September 11-13th, representatives from the Committee for the Defense of the Water and Páramo of Santurbán, a local coalition in the area affected by the mine, met with officials of the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), to alert them to illegalities and socio-environmental risks associated with the Angostura mine project in Colombia, in which the IFC invested four years ago. The Committee was accompanied by representatives from the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO), and MiningWatch Canada. IFC bought shares in Eco Oro Minerals, which hopes to open a large scale gold mine in the Santurbán páramo, a source of fresh water for millions of Colombians, habitat for endemic and threatened species, and important for climate change mitigation through the capture of atmospheric carbon. The delegation emphasized that mining puts all of this at risk and as such, according to Colombian legislation and international norms, is prohibited in páramo ecosystems. They added that cumulative effects should have been considered because the Angostura project has stimulated interest in a possible mining district in the area, in which extensive areas have been concessioned to various mining companies and that has also been affected by the armed conflict. In 2012, the Committee, with support from its allies, presented a complaint to IFC’s accountability mechanism, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO). As a result, the CAO opened an investigation to determine whether the IFC adequately evaluated the social and environmental risks associated with this project before making its investment. The results of the investigation will likely be published before the end of the year. "We hope that, as a result of the CAO report, IFC will withdraw its investment from this mining project, since there is no way that Angostura can live up to the World Bank policies," remarked Erwing Rodríguez, a member of the Committee. "This is a very important case in Santander and the whole country. Through thousands-strong marches and many other actions in defense of water, páramos and territory, we have made it clear that we do not support large-scale mining in the Santurbán páramo," stated Miguel Ramos, another Committee member. A lawyer for AIDA, Carlos Lozano Acosta, continued: "This is a key case because it will set a precedent in the region with regard to the protection of páramos, which are vital for the provision of water and in the fight against climate change." "The World Bank is taking on an unnecessary and unprofitable risk. The value of the shares in Eco Oro that the IFC purchased has considerably dropped. This project is not good for the páramo, for Colombians, or for the IFC. We don’t understand why the IFC insists on maintaining this investment," concluded Kris Genovese of SOMO.

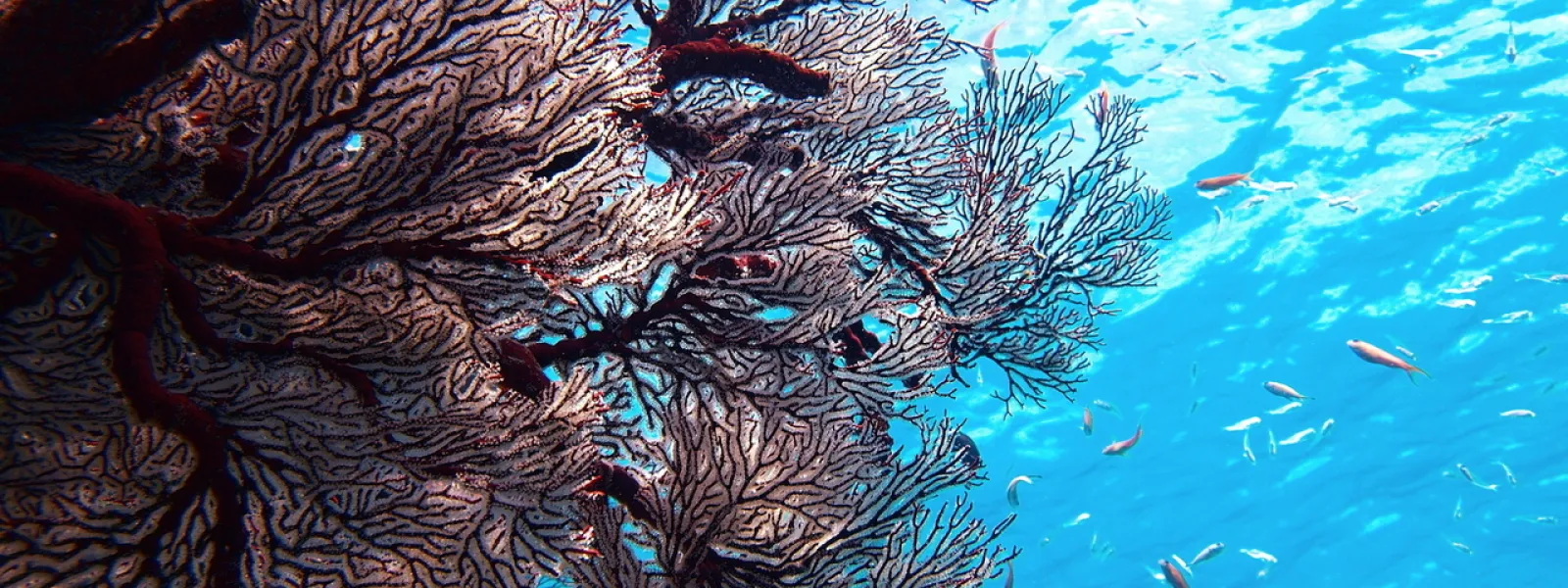

Read moreTri-national organization to investigate Mexico for environmental enforcement in Gulf of California development

The Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) recommended a thorough investigation of Mexico’s systemic failure to enforce its environmental law when authorizing the construction of tourism resorts in the Gulf of California, Mexico. The Gulf region contains many vulnerable ecosystems, endangered species. Mexico City, Mexico. The Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) — an intergovernmental organization created under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Canada, Mexico and the U.S. — has recommended a thorough investigation of Mexico’s systemic failure to enforce its environmental law when authorizing the construction of mega tourism resorts in an important area of the Gulf of California. This investigation comes in response to a citizen petition submitted by the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA) and its partner organization Earthjustice on behalf of 11 local and international organizations. The petition uses the permitting of four mega resorts in this vulnerable region to demonstrate how environmental violations are prevalent. The Gulf of California is a vast area—comprised of the States of Sonora, Sinaloa, Nayarit, Baja California and Southern Baja California. The area contains sensitive ecosystems such as coral reefs and coastal mangroves, and is home to endangered species (whales, manta rays, sharks and turtles, among others), migratory birds, and traditional fishing communities. The latter depend on the local tuna, sardine, shrimp and squid fisheries, which provide employment for nearly 50,000 people. Yet, the Mexican government authorized the construction of three mega resorts in that area—Paraíso del Mar, Entre Mares, and Playa Espíritu—without complying with laws related to environmental impact assessment, endangered species protection, and coastal ecosystem conservation. With these projects, the natural environment in the Gulf of California, and the wildlife and human communities that depend on it, have been put at risk. The CEC Secretariat based its recommendation to conduct a detailed investigation and prepare a "factual record" on the lack of appropriate environmental impact assessments for the projects. The decision does not include Cabo Cortés project, because this project’s environmental permit was recently revoked. "Projects like Playa Espíritu, located in Marismas Nacionales [one of Mexico’s largest wetlands and a key mangrove forest], impact small local companies and the fishing sector. Fisheries are harmed when the mangroves are damaged because these wetlands are a critical nursery and reproductive site for fish," said Carlos Simental of the Ecological Network for the Development of Escuinapa (Red Ecologista por el Desarrollo de Escuinapa - REDES), one of the petitioners. The Gulf of California and its rich biodiversity face a serious problem. Among many examples and according to recent studies, the brown pelicans in the area are not reproducing as they used to, likely due to climatic changes and lack of food due to overfishing. Tourism development that is poorly planned and fails to comply with the laws aggravates the situation. "We hope the Mexican government will receive feedback on how it makes decisions related to environmental impact assessments for tourism development in the region", said Sandra Moguel, an AIDA attorney. "With the preparation of this factual record, we are seeking improvements in the environmental impact assessment process on various fronts. These include the consideration of cumulative impacts—both from separate projects and from all components that comprise any single development—as well as the use of best available information, and inclusion of effective measures for protecting endangered species and mangroves, as required by Mexican law and treaties that Mexico has ratified." The investigation of what has happened in the Gulf of California could yield positive outcomes such as legal reforms, dialogue to improve environmental impact assessment processes, and the design of sustainable tourism projects that involve local communities from the outset. The Council of the CEC, a panel of high-ranking environmental officials from Canada, the United States and Mexico, will decide within two months whether or not they accept the recommendation to develop a factual record. "The Secretariat’s recommendation points to a serious concern that Mexico is failing to effectively enforce environmental laws in the Gulf of California," said Martin Wagner, Director of the International Program of Earthjustice. "This environmental treasure is home to incredible marine biodiversity; it is a critical source of protein for the Mexican people and needs long-term protection. No mega-resort, most of which stem from foreign investment, should be exempt from complying with Mexican environmental protections."

Read moreMexico illegally authorizes hydropower dam

The permit for the project on the San Pedro Mezquital River violates national and international environmental and human rights laws. Mexico City, Mexico. In violation of national and international environmental and human rights laws, on September 18, 2014 Mexico’s environmental authority (SEMARNAT) authorized construction of the Las Cruces hydroelectric project in the state of Nayarit. On behalf of communities and indigenous peoples who will be harmed by the project, the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA) will enlist the aid of United Nations Special Rapporteurs and of the Ramsar Secretariat, who oversees implementation of a wetlands-protection treaty. AIDA will ask these authorities to deem the permit process illegal and demand that the Mexican Government revoke its authorization. In its permit process, SEMARNAT ignored international laws requiring prior consultation with indigenous peoples, who must give their free, prior, and informed consent to the project. These actions are required by the International Labour Organization Convention No. 169 and by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In the permit, SEMARNAT recognizes that the communities of San Blasito and Saycota, which will be evicted as a result of construction, were unaware of the consultation notices that the Federal Electricity Commission (FEC) allegedly posted. "International standards require more than just telling the indigenous people about the project, as FEC did in this case [1]," said Maria José Veramendi, senior attorney at AIDA. "Affected communities must participate since the planning phase. And consultation has to followed by traditional decision-making methods. Before and during consultation, affected people must be provided with precise information on the consequences of the project, with the objective of reaching an agreement," she added. Construction of Las Cruces Dam will force eviction of indigenous peoples, most of them Cora, and harm 14 sacred Cora and Huichol sites. These impacts violate their human rights to adequate housing, water, sustainable livelihoods, culture, and education. The dam will also reduce flow to Marismas Nacionales, which is listed as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty for wetland protection. Reduced flow will harm fishing and agriculture that sustains river communities. In 2009, the Ramsar Secretariat exhorted the Mexican Government to consider the environmental goods and services, and the cultural heritage, of the region before authorizing Las Cruces. That recommendation was ignored. "The Ramsar Convention does not prohibit infrastructure in this kind of ecosystem, but it does establish criteria and standards to guide wetland management [2]," said AIDA attorney Sandra Moguel. "As the authority in charge of ensuring compliance with Mexico’s international environmental commitments, SEMARNAT should have taken the Convention’s guidelines into account. It’s especially regrettable that SEMARNAT ignored the Ramsar Secretariat’s specific recommendations for Marismas Nacionales," said Moguel. SEMARNAT also ignored the technical opinion of the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (CONAPESCA). The Commission pointed out that if Las Cruces is built, fish populations in Nayarit and Sinaloa will dramatically decrease, because they depend on Marismas Nacionales, which in turn depend on the fresh water and nutrients supplied by the San Pedro River. "This permit is a setback," said Moguel. "But AIDA will work closely with international legal authorities until we secure justice for the environment and affected communities." [1] Autorización de Impacto Ambiental del proyecto hidroeléctrico Las Cruces, p. 57 (in Spanish) [2] Autorización de Impacto Ambiental del proyecto hidroeléctrico Las Cruces, p. 62 (in Spanish)

Read moreClimate Marchers to Global Leaders: No dirty energy in the Green Climate Fund

New York, NY – As world leaders prepared to announce pledges of climate action and money for the Green Climate Fund, thousands of people flooded the streets of New York City yesterday demanding a financial commitment to clean energy and climate-resilient solutions. Heads of state are gathering at the United Nations tomorrow, at the invitation of UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon, in an attempt to jump-start negotiations for a new global climate deal. According to Janet Redman, climate policy director at the Institute for Policy Studies, “Reaching an agreement to stabilize the climate rests on developed countries making good on their promises. Contributions to the Green Climate Fund are past due. We need to see serious commitments from our governments to deliver financing for low-carbon, climate-friendly development now.” Andrea Rodríguez, Mexico-based legal advisor for the climate change program of the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), added, “Billions of people still lack access to energy. The Green Climate Fund should support communities to meet that need through truly clean, decentralized, sustainable renewable energy. Despite the interest from various sectors in promoting carbon capture, natural gas, and large dams as climate solutions, this institution should not provide financial support for any project that emits greenhouse gas pollution.” The policies established by the Fund's 24 board members, from both developed and developing countries, have so far not excluded any energy sector from receiving finance, increasing the risk that dirty projects could ultimately receive support. “Dirty energy is more than fossil fuels,” noted Zachary Hurwitz, a consultant for International Rivers. “Hydropower dams can release methane, they can destroy carbon-sequestering forests, and they can displace thousands of people. And there’s nothing clean about the human rights violations that all too often result.” Lidy Nacpil, director of Jubilee South Asia Pacific Movement on Debt and Development, based in the Philippines, said, “In my country, we’re already facing the devastation of climate change. Wealthy industrialized countries have a legal and moral obligation to repay their climate debt and support adaptation through the Green Climate Fund. But that’s not enough. The fund must not exacerbate climate change and its impacts by financing dirty energy.” Additional information: Read the latest commentary from the Institute for Policy Studies on the Green Climate Fund. Read the Global South Position Statement on the Green Climate Fund. Read the open letter to governments, international institutions and financial mechanisms to stop considering large dams as clean energy and to implement real solutions to climate change.

Read morePeople harmed by environmental contamination in La Oroya have been waiting for seven years for the State to guarantee their rights

In 2007, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) asked the Peruvian State to provide medical care and institute environmental controls. These measures have yet to be implemented fully and the health of the affected people continues to deteriorate. The IACHR has yet to reach a final decision in the case. La Oroya, Peru. Seven years have passed since the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) asked the Peruvian State to adopt precautionary measures in favor of the individuals affected by toxic contamination in the city of La Oroya. Those affected, including boys and girls, still have not received the medical attention they require and their health continues to deteriorate. On August 31, 2007, the IACHR granted precautionary measures in favor of 65 inhabitants of La Oroya who were poisoned by air, water, and soil contaminated by lead, arsenic, cadmium, and sulfur dioxide coming from the metallurgical complex of the Doe Run Perú Corporation. In light of the gravity and urgency of the situation, the Commission asked the Peruvian State to take actions necessary to diagnose and provide specialized medical treatment to affected persons whose personal integrity or lives were at risk of irreparable harm. Although some medical attention was provided, the required comprehensive, specialized care has not. Now there are dire risks of setbacks. To date, the Health Strategy for Attending to Persons Affected by Contamination with Heavy Metals and Other Chemical Substances, which is operating in the La Oroya Health Center, does not have an assured budget starting in September and for the remainder of the year. The Strategy is essential for complying with the precautionary measures, given that the diagnosis and specialized medical treatment for the beneficiaries depend on it. Without a budget, the continuity of the medical personnel attending not only to the beneficiaries but also to the entire population of La Oroya will become unviable. "The precautionary measures continue to be in force; after seven years, there has not been full compliance with them. Nonetheless, the State insists on requesting that they be lifted, despite the fact that the health of the population is deteriorating and constant risk [exists]," declared María José Veramendi Villa, attorney for the Inter-American Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). On a related note, the IACHR continues to study the suit filed in 2006 for violations of the human rights of the same group of affected persons. The case is based on the failure of the Peuvian State to adequately control the activities of the metallurgical complex and protect the health and other rights of the affected persons. Regrettably, these individuals’ situation is worsening, and five years after accepting the suit, the IACHR has yet to reach a final decision. "Delay affects us more and more all the time. Our maladies are worsening. During this time, we have lost many of our fellows and seen our children fall ill," declared one of the affected individuals whose name is being withheld for reasons of security. Currently the metallurgical complex is undergoing a process of liquidation, but its operations will continue during the process of being sold. However, in May the complex had to suspend its operations because its suppliers stopped providing it with concentrates due to the company’s financial problems. "Although operations have been suspended, the violations of the individuals’ human rights have already occurred. Therefore, the Peruvian State must comply with its human rights obligations and guarantee that the company and its new owners comply with their obligations to protect the environment and human health," stated Jorge Abrego, attorney for the Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos [Association in Favor of Human Rights] (APRODEH).

Read more