Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

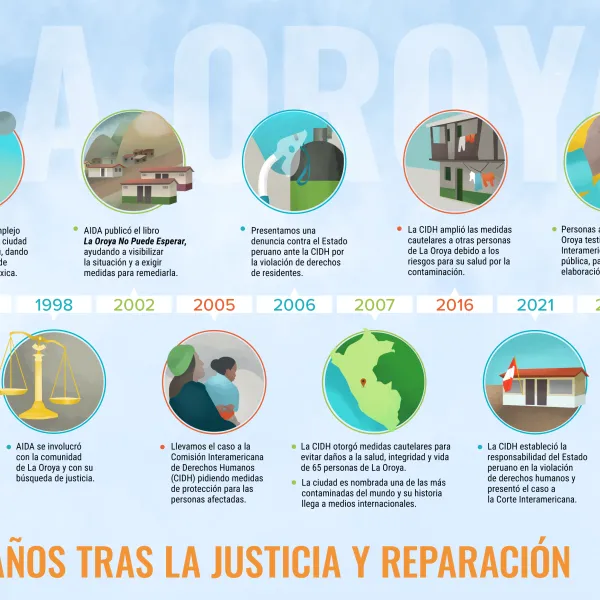

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Civil society organizations denounce assassination of member of Movimiento Ríos Vivos in Colombia

We stand in solidarity with the Movimiento, and we request that the Colombian State investigate this act and punish those responsible. Furthermore, we ask that Colombia adopt urgent and effective measures to stop ongoing violence against environmental defenders. The undersigned national and international organizations categorically condemn the assassination in Colombia of Mr. Hugo Albeiro George Pérez, member of Movimiento Ríos Vivos. Movimiento Ríos Vivos denounced the murder of Mr. George, who is a member of the Asociación de Víctimas y Afectados por Megaproyectos (ASVAM) El Aro—part of Movimiento Ríos Vivos Antioquia—and who, along with his family, was affected by the construction of the Hidroituango dam. The incident, in which his nephew Domar Egidio Zapata George was also killed, occurred on May 2, 2018, in Puerto Valdivia, Antioquia, in the context of regional community mobilizations against the social and environmental risks of the damming of the Cauca River. Hidroituango would be the largest dam in Colombia, with a height of 225 meters and a storage capacity of 20 million cubic meters of water. The project will affect 12 municipalities and impact thousands of families who depend on the river. The project is being financed by a loan package from IDB Invest, the private-sector arm of the Inter-American Development Bank. For defending the land and the Cauca River, Movimiento Ríos Vivos has been the target of threats, intimidation, and human rights violations. The owners of the Hidroituango project must respect human rights and act with due diligence in assessing the impacts of the dam’s construction. In response to the incident, we express our solidarity with Movimiento Ríos Vivos and with the family of Hugo Albeiro George Pérez. We request that the Office of the Attorney General of Colombia investigate this act in an expedited manner and that the appropriate court penalize those responsible. Likewise, and in the context of worsening violence against environmental defenders in the region, we demand that the government guarantee a safe setting for the work of Movimiento Ríos Vivos and to take all necessary precautions to stop the threats, intimidation, and murders against those who defend the environment and their territory. Finally, we request that environmental authorities investigate the impacts communities suffer due to the damming of the Cauca River and that the government provide assistance to the families affected by the project. Accion Ecologica, RedLar Ecuador. Afro-Colombian Solidarity Network. Alianza Internacional de Habitantes. Alianza para la Conservación y el Desarrollo, Panamá. Asamblea Veracruzana de Iniciativas y Defensa Ambiental, Lavida, México. Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense. Bank Information Center. Bretton Woods Project, Londres. CEE Bankwatch Network, Hungría Center for International Environmental Law, Estados Unidos. Centro de Derechos Económicos y Sociales, Ecuador. Coordinadora de Afectados por Grandes Embalses y Trasvases, Coagret. Colombia Grasssrooots Support, New Jersey, Estados Unidos. Colombia Human Rights Committee, Washington, DC, Estados Unidos. Colombia Land Rights Monitor. Consejo de los Pueblos Wuxtaj/CPO, Guatemala. Convergencia por los Derechos Humanos, Guatemala. Derecho, Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Perú. Due Process of Law Foundation, Estados Unidos. Earthrights International. Ecosistemas Chile, Chile. Environmental Investigation Agency, Estados Unidos. Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Argentina. Fundación Chile Sustentable, Chile. Fundar, Mexico. Front Line Defenders, Reino Unido. Global Witness, Reino Unido. IISCAL, Estados Unidos. International Accountability Project, Estados Unidos. International Labor Rights Forum. International Rivers. Latin America Working Group, Estados Unidos. Movement for Peace in Colombia, New York, Estados Unidos. Movimiento Mexicano de Afectados por las Presas y en Defensa de los Ríos, México. Movimiento Victoriano Lorenzo. Not1More. Oxfam. Plataforma Continental Somos una América. Pueblos Unidos de la Cuenca Antigua. Servicios para una Educación Alternativa, México. Taller de Comunicación Ambiental, Rosario. Washington Office on Latin America, Estados Unidos. Press contact: Víctor Quintanilla, AIDA, +521 5570522107, [email protected]

Read more

Civil society organizations denounce assassination of member of Movimiento Ríos Vivos in Colombia

We stand in solidarity with the Movimiento, and we request that the Colombian State investigate this act and punish those responsible. Furthermore, we ask that Colombia adopt urgent and effective measures to stop ongoing violence against environmental defenders. The undersigned national and international organizations categorically condemn the assassination in Colombia of Mr. Hugo Albeiro George Pérez, member of Movimiento Ríos Vivos. Movimiento Ríos Vivos denounced the murder of Mr. George, who is a member of the Asociación de Víctimas y Afectados por Megaproyectos (ASVAM) El Aro—part of Movimiento Ríos Vivos Antioquia—and who, along with his family, was affected by the construction of the Hidroituango dam. The incident, in which his nephew Domar Egidio Zapata George was also killed, occurred on May 2, 2018, in Puerto Valdivia, Antioquia, in the context of regional community mobilizations against the social and environmental risks of the damming of the Cauca River. Hidroituango would be the largest dam in Colombia, with a height of 225 meters and a storage capacity of 20 million cubic meters of water. The project will affect 12 municipalities and impact thousands of families who depend on the river. The project is being financed by a loan package from IDB Invest, the private-sector arm of the Inter-American Development Bank. For defending the land and the Cauca River, Movimiento Ríos Vivos has been the target of threats, intimidation, and human rights violations. The owners of the Hidroituango project must respect human rights and act with due diligence in assessing the impacts of the dam’s construction. In response to the incident, we express our solidarity with Movimiento Ríos Vivos and with the family of Hugo Albeiro George Pérez. We request that the Office of the Attorney General of Colombia investigate this act in an expedited manner and that the appropriate court penalize those responsible. Likewise, and in the context of worsening violence against environmental defenders in the region, we demand that the government guarantee a safe setting for the work of Movimiento Ríos Vivos and to take all necessary precautions to stop the threats, intimidation, and murders against those who defend the environment and their territory. Finally, we request that environmental authorities investigate the impacts communities suffer due to the damming of the Cauca River and that the government provide assistance to the families affected by the project. Accion Ecologica, RedLar Ecuador. Afro-Colombian Solidarity Network. Alianza Internacional de Habitantes. Alianza para la Conservación y el Desarrollo, Panamá. Asamblea Veracruzana de Iniciativas y Defensa Ambiental, Lavida, México. Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense. Bank Information Center. Bretton Woods Project, Londres. CEE Bankwatch Network, Hungría Center for International Environmental Law, Estados Unidos. Centro de Derechos Económicos y Sociales, Ecuador. Coordinadora de Afectados por Grandes Embalses y Trasvases, Coagret. Colombia Grasssrooots Support, New Jersey, Estados Unidos. Colombia Human Rights Committee, Washington, DC, Estados Unidos. Colombia Land Rights Monitor. Consejo de los Pueblos Wuxtaj/CPO, Guatemala. Convergencia por los Derechos Humanos, Guatemala. Derecho, Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Perú. Due Process of Law Foundation, Estados Unidos. Earthrights International. Ecosistemas Chile, Chile. Environmental Investigation Agency, Estados Unidos. Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Argentina. Fundación Chile Sustentable, Chile. Fundar, Mexico. Front Line Defenders, Reino Unido. Global Witness, Reino Unido. IISCAL, Estados Unidos. International Accountability Project, Estados Unidos. International Labor Rights Forum. International Rivers. Latin America Working Group, Estados Unidos. Movement for Peace in Colombia, New York, Estados Unidos. Movimiento Mexicano de Afectados por las Presas y en Defensa de los Ríos, México. Movimiento Victoriano Lorenzo. Not1More. Oxfam. Plataforma Continental Somos una América. Pueblos Unidos de la Cuenca Antigua. Servicios para una Educación Alternativa, México. Taller de Comunicación Ambiental, Rosario. Washington Office on Latin America, Estados Unidos. Press contact: Víctor Quintanilla, AIDA, +521 5570522107, [email protected]

Read more

Brazil must respond to human rights violations caused by the Belo Monte Dam

In representation of communities affected by the Belo Monte Dam, we have submitted final arguments in the case against Brazil before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The report presents scientific evidence of the forced displacement of indigenous and traditional communities, the mass die-off of fish, differentiated harms to men and women, and threats to the survival of local communities in the Brazilian Amazon. Washington, DC, United States and Altamira, Brazil. Furthering the formal complaint against the State of Brazil for human rights violations caused by the construction of the Belo Monte Dam, organizations representing affected communities presented their final arguments before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. They demonstrate the damages Belo Monte has caused to indigenous and traditional communities, and residents of Altamira, the city closest to the dam. “Human rights violations are a daily occurence for those affected by the dam, so it’s urgent that our petition before the Commission advance to sanction the government and guarantee our rights,” proclaimed Antônia Melo, coordinator of the Movimiento Xingu Vivo para Siempre, a citizens’ collective formed in the face of the dam’s implementation. The report presented before the Commission shows that the damages resulted from a severe lack of foresight and inadequate evaluation, as well as from failure to comply with the conditions for operation established by the government. The many risks denounced prior to the dam’s construction have since become long-term damages—many of which have affected men and women, and youth and the elderly, in different ways. “This report is a vital step forward for the people of the Xingu River basin, who are now closer than ever to achieving justice, forcing Brazil to respond to the violations committed, and ensuring that what happened on the Xingu never happens again,” said Astrid Puentes Riaño, co-director of the Inter-American Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA). Together with the Paraense Society for Human Rights (SDDH) and Justiça Global, AIDA represents the affected communities before the Commission. The report also documents the displacement of indigenous and traditional communities forced to leave their territories without adequate alternatives, placing their cultural survival at risk. Among the affected populations are communities dedicated to fishing, who have not yet been compensated for the loss of livelihood. The dam has caused mass die-offs of fish and, although authorities have imposed millions in fines, the report demonstrates that the underlying problem has not been resolved. Local communities now have limited use of the Xingu River as a source of food, sustenance, transportation and entertainment. The report also documents—among other serious harms—the disappearance of traditional trades, such as brickmakers and cart drivers, and of traditional cultural practices. Women, for example, have stopped giving birth in their homes and must now go to a hospital, a reality that has drastically worsened due to the oversaturation of health and education services in Altamira caused by the recent population surge. The complaint against Brazil was presented before the Commission in 2011, the year the international organism granted protective measures to indigenous people affected by the dam’s construction. The case against Brazil officially opened in December 2015. Then, last October, in a rare move designed to speed up the processing of the case, the Commission decided to unite two stages that, as a rule, are normally processed separately. Under this framework, the organizations and the State are required to present their final arguments, after which the Commission will make a decision. “We hope the Commission refers the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights as soon as possible, and that it recommends Brazil adopt the measures necessary to protect the life, integrity, and right to property of the indigenous and traditional communities affected by the dam,” said Raphaela Lopes, attorney at Justiça Global. “After being subject to all forms of rights violations, starting from the very beginning of this project, these communities need integral reparation; their right to free, prior and informed consent was not honored.” The Commission must now prepare a report to conclude whether or not human rights violations occurred as a result of the Belo Monte Dam, in which it may issue recommendations for remediation. If those recommendations are unfulfilled, the case may be referred to the Inter-American Court on Human Rights, which has the power to issue a ruling condemning Brazil. Belo Monte has been in operation since early 2015, though a series of judicial suspensions resulting from non-compliance with its permits means that construction has yet to be completed. Although Belo Monte has caused great harm to the people of the Xingu, Brazil now has an opportunity to avoid inflicting more damage and begin making efforts to better their quality of life. For that to happen, a prompt decision by the Commission is vital. Find more information about the case here. Press contacts: Víctor Quintanilla (México), AIDA, [email protected], +521 5570522107 Raphaela Lopes (Brasil), Justiça Global, [email protected], + 55 21 99592-7017

Read more