Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

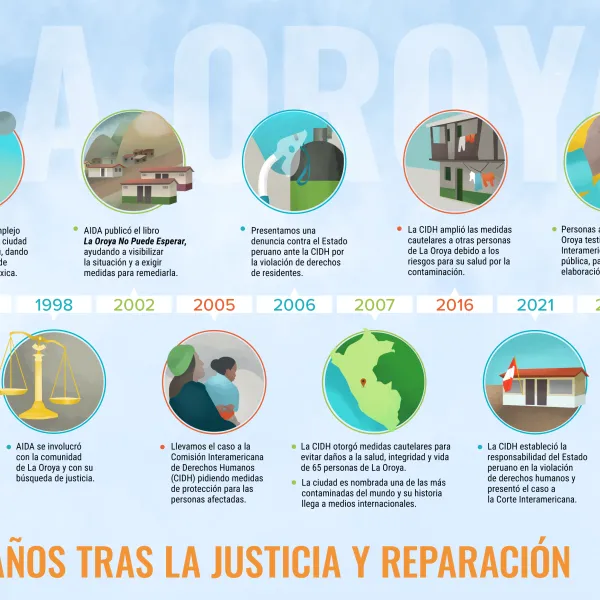

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

To keep corals healthy, we must protect herbivorous fish

We all know coral reefs are fragile environments, highly vulnerable to climate change and pollution. But did you know they also had to compete for light and oxygen with the tiny macro-algae that cover their surface? That’s why some of corals' best friends are herbivorous fish—species like parrotfish and surgeonfish that feed on algae, helping to keep corals healthy. But in the Caribbean, unsustainable fishing practices are causing a decline in populations of parrotfish (and other herbivorous fish), putting the health of corals at risk. That’s why, in AIDA’s marine program, we’re launching a large-scale project dedicated to the conservation of herbivorous fish throughout Latin America—focused on the nations of Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Panama. Herbivorous fish conservation The parrotfish is one of the most important fish living in coral reefs. They spend most of the day nibbling on corals, cleaning algae from their surface. They also eat dead corals—those bits and pieces that protrude from the reef—and later excrete them as white sand. A key element to maintaining sustainable fisheries is catching only adult fish—those that have already matured and reproduced. But in the Caribbean right now, people are fishing juvenile parrotfish. Though not a commercial species, parrotfish are being captured because they’re some of the only fish left in the reef. The irresponsible nature of commercial fishing in the region has caused a drastic decline in both commercial and herbivorous fish. “A key element of maintaining a sustainable fishery is catching only adult fish, which have already matured and reproduced. But what’s happening in the Caribbean is the fishing of young parrotfish,” explained Magie Rodríguez, AIDA marine attorney. Most fishing is done with gillnets and hooks, which cause high levels of by-catch—unwanted populations of marine species caught in commercial fishing. Harpoons and traps are also used, which prevent younger, smaller fish from escaping and continuing their life cycle. Surgeonfish and damselfish are two other herbivorous fish—both small and quite beautiful—falling victim to irresponsible fishing practices. Their popularity in tropical home aquariums has led to a decline in their wild populations. Remember Dory, from Finding Nemo? She was a surgeonfish, and the movie’s popularity led to an increased demand for her species in aquariums. What the movie didn’t tell you is that the surgeonfish’s small, sharp teeth are highly adept at chewing algae, preventing the plantlife from essentially choking coral reefs of oxygen and light. Conservation strategies AIDA’s project for the conservation of herbivorous fish in the Caribbean is in its initial phases. Our objective is the implementation of diverse strategies, across the six Latin American nations, to protect these fish and, by extension, the reefs they call home. “To restore the balance of the coral ecosystem, it’s necessary to achieve the recovery not just of herbivorous fish populations, but also of commercial species,” Rodríguez said. So we’re talking not just about fishing bans, but also about the general adoption of sustainable fishing tools that take into account the tourism potential of coral reefs. The project will also contemplate adequate wastewater management strategies, consumer education, and collaboration between governments, NGOs, universities and scientists. Corals are, among other things, a source of economic income and food for coastal communities that live from fishing and tourism. Plus, they are natural barriers against storms and hurricanes. “Corals do a lot for us and we have to take care of them,” Rodríguez added. “We’ve come to find that the best thing we can do to keep corals healthy is to protect the herbivorous fish that call them home.”

Read more

To keep corals healthy, we must protect herbivorous fish

We all know coral reefs are fragile environments, highly vulnerable to climate change and pollution. But did you know they also had to compete for light and oxygen with the tiny macro-algae that cover their surface? That’s why some of corals' best friends are herbivorous fish—species like parrotfish and surgeonfish that feed on algae, helping to keep corals healthy. But in the Caribbean, unsustainable fishing practices are causing a decline in populations of parrotfish (and other herbivorous fish), putting the health of corals at risk. That’s why, in AIDA’s marine program, we’re launching a large-scale project dedicated to the conservation of herbivorous fish throughout Latin America—focused on the nations of Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Panama. Herbivorous fish conservation The parrotfish is one of the most important fish living in coral reefs. They spend most of the day nibbling on corals, cleaning algae from their surface. They also eat dead corals—those bits and pieces that protrude from the reef—and later excrete them as white sand. A key element to maintaining sustainable fisheries is catching only adult fish—those that have already matured and reproduced. But in the Caribbean right now, people are fishing juvenile parrotfish. Though not a commercial species, parrotfish are being captured because they’re some of the only fish left in the reef. The irresponsible nature of commercial fishing in the region has caused a drastic decline in both commercial and herbivorous fish. “A key element of maintaining a sustainable fishery is catching only adult fish, which have already matured and reproduced. But what’s happening in the Caribbean is the fishing of young parrotfish,” explained Magie Rodríguez, AIDA marine attorney. Most fishing is done with gillnets and hooks, which cause high levels of by-catch—unwanted populations of marine species caught in commercial fishing. Harpoons and traps are also used, which prevent younger, smaller fish from escaping and continuing their life cycle. Surgeonfish and damselfish are two other herbivorous fish—both small and quite beautiful—falling victim to irresponsible fishing practices. Their popularity in tropical home aquariums has led to a decline in their wild populations. Remember Dory, from Finding Nemo? She was a surgeonfish, and the movie’s popularity led to an increased demand for her species in aquariums. What the movie didn’t tell you is that the surgeonfish’s small, sharp teeth are highly adept at chewing algae, preventing the plantlife from essentially choking coral reefs of oxygen and light. Conservation strategies AIDA’s project for the conservation of herbivorous fish in the Caribbean is in its initial phases. Our objective is the implementation of diverse strategies, across the six Latin American nations, to protect these fish and, by extension, the reefs they call home. “To restore the balance of the coral ecosystem, it’s necessary to achieve the recovery not just of herbivorous fish populations, but also of commercial species,” Rodríguez said. So we’re talking not just about fishing bans, but also about the general adoption of sustainable fishing tools that take into account the tourism potential of coral reefs. The project will also contemplate adequate wastewater management strategies, consumer education, and collaboration between governments, NGOs, universities and scientists. Corals are, among other things, a source of economic income and food for coastal communities that live from fishing and tourism. Plus, they are natural barriers against storms and hurricanes. “Corals do a lot for us and we have to take care of them,” Rodríguez added. “We’ve come to find that the best thing we can do to keep corals healthy is to protect the herbivorous fish that call them home.”

Read more

To keep corals healthy, we must protect herbivorous fish

We all know coral reefs are fragile environments, highly vulnerable to climate change and pollution. But did you know they also had to compete for light and oxygen with the tiny macro-algae that cover their surface? That’s why some of corals' best friends are herbivorous fish—species like parrotfish and surgeonfish that feed on algae, helping to keep corals healthy. But in the Caribbean, unsustainable fishing practices are causing a decline in populations of parrotfish (and other herbivorous fish), putting the health of corals at risk. That’s why, in AIDA’s marine program, we’re launching a large-scale project dedicated to the conservation of herbivorous fish throughout Latin America—focused on the nations of Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Panama. Herbivorous fish conservation The parrotfish is one of the most important fish living in coral reefs. They spend most of the day nibbling on corals, cleaning algae from their surface. They also eat dead corals—those bits and pieces that protrude from the reef—and later excrete them as white sand. A key element to maintaining sustainable fisheries is catching only adult fish—those that have already matured and reproduced. But in the Caribbean right now, people are fishing juvenile parrotfish. Though not a commercial species, parrotfish are being captured because they’re some of the only fish left in the reef. The irresponsible nature of commercial fishing in the region has caused a drastic decline in both commercial and herbivorous fish. “A key element of maintaining a sustainable fishery is catching only adult fish, which have already matured and reproduced. But what’s happening in the Caribbean is the fishing of young parrotfish,” explained Magie Rodríguez, AIDA marine attorney. Most fishing is done with gillnets and hooks, which cause high levels of by-catch—unwanted populations of marine species caught in commercial fishing. Harpoons and traps are also used, which prevent younger, smaller fish from escaping and continuing their life cycle. Surgeonfish and damselfish are two other herbivorous fish—both small and quite beautiful—falling victim to irresponsible fishing practices. Their popularity in tropical home aquariums has led to a decline in their wild populations. Remember Dory, from Finding Nemo? She was a surgeonfish, and the movie’s popularity led to an increased demand for her species in aquariums. What the movie didn’t tell you is that the surgeonfish’s small, sharp teeth are highly adept at chewing algae, preventing the plantlife from essentially choking coral reefs of oxygen and light. Conservation strategies AIDA’s project for the conservation of herbivorous fish in the Caribbean is in its initial phases. Our objective is the implementation of diverse strategies, across the six Latin American nations, to protect these fish and, by extension, the reefs they call home. “To restore the balance of the coral ecosystem, it’s necessary to achieve the recovery not just of herbivorous fish populations, but also of commercial species,” Rodríguez said. So we’re talking not just about fishing bans, but also about the general adoption of sustainable fishing tools that take into account the tourism potential of coral reefs. The project will also contemplate adequate wastewater management strategies, consumer education, and collaboration between governments, NGOs, universities and scientists. Corals are, among other things, a source of economic income and food for coastal communities that live from fishing and tourism. Plus, they are natural barriers against storms and hurricanes. “Corals do a lot for us and we have to take care of them,” Rodríguez added. “We’ve come to find that the best thing we can do to keep corals healthy is to protect the herbivorous fish that call them home.”

Read more