Project

Protecting the health of La Oroya's residents from toxic pollution

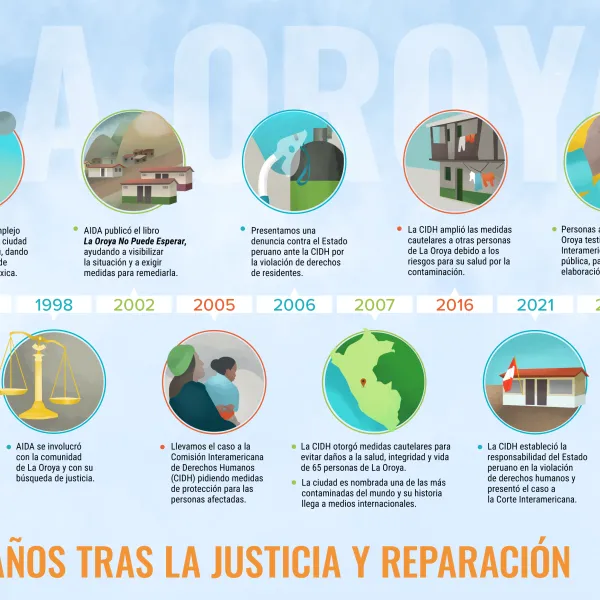

For more than 20 years, residents of La Oroya have been seeking justice and reparations after a metallurgical complex caused heavy metal pollution in their community—in violation of their fundamental rights—and the government failed to take adequate measures to protect them.

On March 22, 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its judgment in the case. It found Peru responsible and ordered it to adopt comprehensive reparation measures. This decision is a historic opportunity to restore the rights of the victims, as well as an important precedent for the protection of the right to a healthy environment in Latin America and for adequate state oversight of corporate activities.

Background

La Oroya is a small city in Peru’s central mountain range, in the department of Junín, about 176 km from Lima. It has a population of around 30,000 inhabitants.

There, in 1922, the U.S. company Cerro de Pasco Cooper Corporation installed the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex to process ore concentrates with high levels of lead, copper, zinc, silver and gold, as well as other contaminants such as sulfur, cadmium and arsenic.

The complex was nationalized in 1974 and operated by the State until 1997, when it was acquired by the US Doe Run Company through its subsidiary Doe Run Peru. In 2009, due to the company's financial crisis, the complex's operations were suspended.

Decades of damage to public health

The Peruvian State - due to the lack of adequate control systems, constant supervision, imposition of sanctions and adoption of immediate actions - has allowed the metallurgical complex to generate very high levels of contamination for decades that have seriously affected the health of residents of La Oroya for generations.

Those living in La Oroya have a higher risk or propensity to develop cancer due to historical exposure to heavy metals. While the health effects of toxic contamination are not immediately noticeable, they may be irreversible or become evident over the long term, affecting the population at various levels. Moreover, the impacts have been differentiated —and even more severe— among children, women and the elderly.

Most of the affected people presented lead levels higher than those recommended by the World Health Organization and, in some cases, higher levels of arsenic and cadmium; in addition to stress, anxiety, skin disorders, gastric problems, chronic headaches and respiratory or cardiac problems, among others.

The search for justice

Over time, several actions were brought at the national and international levels to obtain oversight of the metallurgical complex and its impacts, as well as to obtain redress for the violation of the rights of affected people.

AIDA became involved with La Oroya in 1997 and, since then, we’ve employed various strategies to protect public health, the environment and the rights of its inhabitants.

In 2002, our publication La Oroya Cannot Wait helped to make La Oroya's situation visible internationally and demand remedial measures.

That same year, a group of residents of La Oroya filed an enforcement action against the Ministry of Health and the General Directorate of Environmental Health to protect their rights and those of the rest of the population.

In 2006, they obtained a partially favorable decision from the Constitutional Court that ordered protective measures. However, after more than 14 years, no measures were taken to implement the ruling and the highest court did not take action to enforce it.

Given the lack of effective responses at the national level, AIDA —together with an international coalition of organizations— took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in November 2005 requested measures to protect the right to life, personal integrity and health of the people affected. In 2006, we filed a complaint with the IACHR against the Peruvian State for the violation of the human rights of La Oroya residents.

In 2007, in response to the petition, the IACHR granted protection measures to 65 people from La Oroya and in 2016 extended them to another 15.

Current Situation

To date, the protection measures granted by the IACHR are still in effect. Although the State has issued some decisions to somewhat control the company and the levels of contamination in the area, these have not been effective in protecting the rights of the population or in urgently implementing the necessary actions in La Oroya.

Although the levels of lead and other heavy metals in the blood have decreased since the suspension of operations at the complex, this does not imply that the effects of the contamination have disappeared because the metals remain in other parts of the body and their impacts can appear over the years. The State has not carried out a comprehensive diagnosis and follow-up of the people who were highly exposed to heavy metals at La Oroya. There is also a lack of an epidemiological and blood study on children to show the current state of contamination of the population and its comparison with the studies carried out between 1999 and 2005.

The case before the Inter-American Court

As for the international complaint, in October 2021 —15 years after the process began— the IACHR adopted a decision on the merits of the case and submitted it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after establishing the international responsibility of the Peruvian State in the violation of human rights of residents of La Oroya.

The Court heard the case at a public hearing in October 2022. More than a year later, on March 22, 2024, the international court issued its judgment. In its ruling, the first of its kind, it held Peru responsible for violating the rights of the residents of La Oroya and ordered the government to adopt comprehensive reparation measures, including environmental remediation, reduction and mitigation of polluting emissions, air quality monitoring, free and specialized medical care, compensation, and a resettlement plan for the affected people.

Partners:

Related projects

Toward a law to protect glaciers and water in Chile

More than 70 percent of the world’s fresh water is frozen in glaciers,[1] making these giants the most important freshwater reserves on the planet. The distribution of this wealth has been generous to some countries. According to the Randolph Inventory, the most complete map of glaciers in the world, Chile is the guardian of the largest area of glaciers in South America: 14,600 square miles distributed across thousands of glaciers that reach from the peaks of the Altiplano in the north to the extreme southern tip of the continent. The most dangerous threats to glaciers are climate change and industrial activities near them, especially mining. Through strategic litigation and advocacy, AIDA is working to halt the harms from both of these threats. Climate change has caused the decline of snow and rainfall, as well as an increase in temperature, which reduces the accumulation of ice and increases the melting of glaciers. Mining exploration and exploitation degrade glaciers with road construction, drilling, explosives, and toxic materials. These activities also generate dust that settles on glaciers, making them darker and accelerating their rate of melt. Although we know that water is fundamental for life, and that glaciers are dangerously threatened, surprising littleinternational law protects glaciers. No international treaty aims to preserve them, nor is any such treaty under consideration. At the national level, only Argentina has a law to protect its glaciers. In Chile, draft legislation to protect glaciers has been debated in Congress for many years. Bearing in mind the drought currently plaguing the country, what better reason could there be to develop a SMART legal tool to care for Chilean glaciers? In search of a law The first attempt to enact a law to protect Chile’s glaciers was in 2006. It was driven by the approval of the Pascua-Lama mining project, which threatened the mountainous glaciers in the north of the country. The unsuccessful initiative was shelved in 2007. On May 20, 2014 members of Congress, calling themselves "the Glacier Caucus," proposed a new law to preserve the glaciers. Mining and geothermal companies severely criticized their proposal, which forbade mining and other activities that harm glaciers. This March, the executive branch made a counterproposal. According to environmental organizations, the spirit of the Glacier Caucus law was completely changed in response to mining-industry demands. What follows are points for and against the government’s proposal, based on the minutes in (Spanish) of a collaborative meeting of environmental organizations: Positive Recognizes glaciers as freshwater reservoirs, as providers of ecosystem services, and as national public property. Prohibits applications for rights to harvest glacial water. Strengthens the power of the General Water Directorate to generate information, monitor the status of glaciers, and impose fines. Elevates the legal hierarchy of the glacier inventory. Negative Does not protect all glaciers, only those found in national parks or wildlife reserves. This is a serious oversight, considering that the most threatened glaciers are in the north, where national parks are rare and where they share territory with mining reserves. Worse, still, glaciers in the north supply drinking water to millions of people who live in areas where water is scarce. Could safeguard some glaciers outside of protected areas if the Committee of Ministers for Sustainability considers them "strategic water reserves." The proposal, however, makes no reference to the tools or public funds needed to make such an assessment. The risk is that this designation would eventually be left to consultants who frequently work for mining companies. Leaves glaciers that are not considered “strategic reserves” open to industrial projects, depending on the conclusions of Environmental Impact Assessments. In the past, EIAs have permitted such damaging projects as the Pacua-Lama, Andina 244, Los Bronces, and Los Pelambres mines. States that a project’s environmental permit will only be reviewed if the project currently impacts glaciers in national parks or those declared "strategic reserves." All other glaciers remain subject to the mining and energy projects that are already harming them. Internal debates in Congress will continue. We truly hope the resulting law will provide all glaciers with their due protection and that similar laws will be enacted in the rest of the countries where glaciers hold precious water for future generations. Meanwhile, AIDA’s dedicated legal advocates are working hard to prevent and minimize mining threats to the environment and people. AIDA is currently preparing a guide, Basic Guidelines for the Environmental Impact Assessment of Mining Projects: Recommended Terms of Reference (in Spanish), detailing the comprehensive analysis that must be completed for any proposed mining project. We are advocating with government agencies to conduct thorough assessments before approving new mine projects and, when necessary, we’re pursuing strategic litigation to compel agencies to improve their assessments. We’re also strengthening environmental laws and precedents that apply to extractive industries. In Colombia and Panama, AIDA is actively advocating revisions to the national mining codes, specifically to protect crucial water resources. Bringing international law to bear on the issue, we’re using international agreements to establish precedents that apply to mines broadly. We’ve also begun to create a pool of technical experts to help local communities and governments understand and evaluate proposals for mineral extraction. Please watch this blog for upcoming news about mines, water, and AIDA’s efforts to protect a healthy environment. [1] According to data from Global Water Partnership: http://www.gwp.org/

Read moreInternationally Advocating for Accountability for Human Rights Abuses

Juana[1] is suffering from respiratory problems and her sister has asthma. They live in La Oroya, a small city in Peru’s central Andes. It was years before Juana had access to the information she needed to understand the source of their illnesses: toxic contamination from the Doe Run metal smelter. Although there has been some progress, Juana and the rest of the people affected by the contaminated air in La Oroya still do not receive the specialized and comprehensive medical care they need. In cases like La Oroya, victims don’t always find justice in their own countries and must raise their demands to an international level. One space to do so is the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights public hearings, held twice a year in March and October. AIDA has actively participated in case hearings on specific human rights violations, such as in La Oroya. But we have also requested and received thematic hearings on problems facing Latin American countries or the region as a whole. We have participated alongside and in collaboration with other civil society organizations. "By providing information and arguments, we encourage the Commission to make visible worrisome situations of human rights violations caused by environmental degradation, and to take actions to stop them: develop standards, monitor cases, and make recommendations to States," explained María José Veramendi Villa, senior attorney at AIDA. Last October AIDA and partner organizations called the Commission’s attention to mining and energy projects that force displacement of people and communities in Colombia. We also requested that the Commission develop standards governing displacement caused by large infrastructure projects, and insisted that the Colombian government properly respond to the victims. "These hearings are the most comprehensive and flexible tool to ensure the Commission receives information about the issues that are troubling to the region. There are so many worries, and so many organizations wanting to be heard, that there is not enough time. The hearings are an indicator of the most relevant issues of the times and, through them, civil society develops an agenda of work," said Ana María Mondragón, attorney at AIDA. AIDA returned this month to Washington, D.C., seat of the Commission, to participate in a thematic hearing that brings to the table a current and deepening concern: the predominant role corporations are playing in the violation of human rights in Latin America. One example is the case of Máxima Acuña Chaupe in Cajamarca, Peru. The Yanacocha mining company is interested in developing a project on her territory and, in order to do so, accused her of usurping land. Although a judicial court ruling established Máxima’s innocence, she and her family live in fear that the company may again try to take away their home. The case of the Chaupe family, and many others in the region, demonstrates the importance of bringing this issue before the Commission. "During the hearing, we presented information to fuel debate about opportunities for the Commission to create, implement and strengthen international standards on business and human rights," explained Veramendi Villa. "By doing so, the Commission can urge States to control and/or sanction corporations – like Doe Run Peru and Yanacocha – whose activities harm the environment and violate human rights and ensure access to justice for its victims." [1] Name has been changed to protect confidentiality.

Read more

Organizations request that the IACHR strengthen State obligations to supervise corporate activities that violate human rights

In a hearing before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, they highlighted the opportunities that the Commission has to address the problem through the creation, implementation and strengthening of international standards on business and human rights. Washington D.C. In a hearing before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, civil society organizations requested that the Commission provide renewed attention to the problem, increasingly experienced in the hemisphere, of human rights violations committed by corporations. The hearing was jointly requested by the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), a regional organization; the Association for Human Rights (APRODEH) of Peru; the Center for Human Rights and Environment (CEDHA) of Argentina; and Justiça Global of Brazil. The organizations applauded the Commission’s openness to directly addressing, for the first time, the theme of business and human rights in a public hearing. “Through various mechanisms in recent years, the Commission has received a large amount of information about cases of human rights violations in which corporations have played a central role, but the problem has worsened because of a lack of effective solutions. In this sense, one of the biggest challenges the Commission has is to find ways to address the issue properly and to help both the States and the corporations to fulfill their human rights obligations,” explained Astrid Puentes, co-executive director of AIDA. Through their work, the organizations have seen that most recurrent aspects of the problem include: the impacts of megaprojects and extractive industries on human rights and the environment; difficulties in guaranteeing the right to participation and access to information for affected people and communities; the absence of Human Rights Impact Assessments; systematic violations of labor rights and forced labor practices; the privatization of public security forces to protect business activities; and aggression towards and criminalization of people who defend the environment, their territory and human rights. At the hearing, the organizations reminded that progress has been made in the development international standards on business and human rights. One such example, they explained, is the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. "However, because compliance is voluntary and there are various legal loopholes, this instrument has not been effective enough to prevent the continuation of human rights abuses. Also, effective regulation of territorial and extraterritorial State obligations regarding the responsibilities of transnational corporations on national, regional and international levels does not exist. This sort of vacuum prevents both the safeguarding of people’s rights, and access to appropriate compensation and justice for victims,” said Alexandra Montgomery of Justiça Global. Looking forward, the organizations presented information about the opportunities the Commission has to strengthen the implementation of existing standards. They emphasized the following points: The Commission should promote corporations’ respect for human rights. This includes promoting State responsibility for adequate supervision of business activities and for establishment of binding obligations for them, since the voluntary nature of the Guiding Principles compromises and puts at risk the protection of human rights. Based on the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Human Rights System in relation to the obligations of States to respect and guarantee human rights, the Commission can develop specific measures for States to supervise business activities to ensure that they do not violate human rights. Respect for human rights by States and companies must not be subject to economic or political considerations. It is necessary to strengthen access to justice for victims of human rights abuses by business actors through recommendations for improvement and implementation of accountability mechanisms and international forums, such as the Commission and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. “We hope that as a result of the hearing, the Commission initiates dialogues that incorporate the experience of civil society organizations and of United Nations agencies to strengthen the respect of and guarantees for human rights in the region,” concluded Gloria Cano, of APRODEH.

Read more