Project

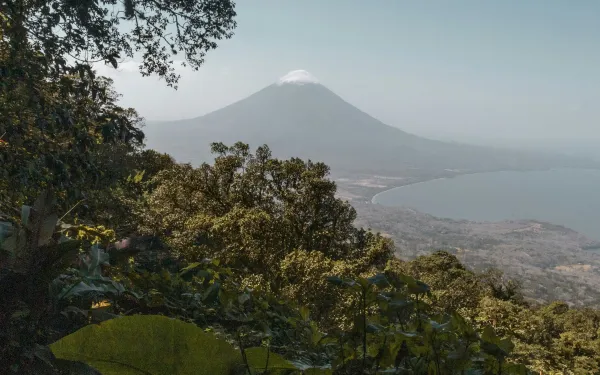

Foto: Andrés ÁngelStopping the spread of fracking in Latin America

“Fracking” is short for hydraulic fracturing, a process used to extract oil and natural gas from historically inaccessible reservoirs.

Fracking is already widespread in the global North, but in Latin America, it is just beginning. Governments are opening their doors to fracking without understanding its impacts and risks, and without consulting affected communities. Many communities are organizing to prevent or stop the impacts of fracking, which affect their fundamental human rights. But in many cases they require legal and technical support.

What exactly is fracking, and what are its impacts?

A straight hole is drilled deep into the earth. Then the drill curves and bores horizontally, making an L-shaped hole. Fracking fluid—a mixture of water, chemicals, and sand—is pumped into the hole at high pressure, fracturing layers of shale rock above and below the hole. Gas or oil trapped in the rock rises to the surface along with the fracking fluid.

The chemical soup—now also contaminated with heavy metals and even radioactive elements from underground—is frequently dumped into unlined ponds. It may seep into aquifers and overflow into streams, poisoning water sources for people, agriculture, and livestock. Gas may also seep from fractured rock or from the well into aquifers; as a result, water flowing from household taps can be lit on fire. Other documented harms include exhausted freshwater supplies (for all that fracking fluid), air pollution from drill and pump rigs, large methane emissions that aggravate global warming, earthquakes, and health harms including cancer and birth defects.

AIDA’s report on fracking (available in Spanish) analyzes the viability of applying the precautionary principle as an institutional tool to prevent, avoid or stop hydraulic fracturing operations in Latin America.

Partners:

Related projects

Native bees and indigenous peoples: an ancestral bond

Did you know that there are bees native to our continent that have been part of the cosmovision and way of life of various indigenous peoples? The native bees or Melipona beesbelong to the tribe of the Meliponini. They are known as "stingless bees" because they do not have a functional stinger, although they have other defense mechanisms, such as biting. There are dozens of species of these bees found from Mexico to Argentina. In some indigenous communities, native bees are considered spiritual and symbolic beings, but they are also valued for their essential functions in sustaining life: by pollinating crops, they are allies in food production; their honey, wax, and propolis have recognized nutritional and healing properties; and they maintain the balance of nature for the conservation of ecosystems. As part of World Bee Day—celebrated every year on May 20 to raise awareness, promote and encourage actions to protect bees and other pollinators—we would like to highlight the work of some communities that honor and care for native bees in a variety of ways, and in doing so, care for and preserve their own cultures. A work of mutual care The breeding and use of melipona bees, native to the Americas, is an ancestral practice for several indigenous peoples. This activity, called meliponiculture, is part of their way of life and worldview. The introduction of the domestic bee (Apis mellifera) from Europe drastically reduced this practice. However, many communities have preserved it, protecting native bees from extinction and ensuring biodiversity in their territories. We have examples of this across the continent. Guatemala The warm forests of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, are the preferred habitat of native bees and are home to the greatest diversity of bees in the country. Their conservation is in the hands of Q'eqchi Mayan families and small producers who build technological hives or "bee houses." Peru Through her Sumak Kawsay initiative, Ysabel Calderón is promoting the conservation of native bees by restoring their habitat in Lambayeque, Peru. Calderón has planted more than 1,000 trees in Lambayeque and increased the native bee population. This has also created jobs for a group of women in the region. Argentina In Argentina's Gran Chaco, Silvia Godoy and other small-scale honey producers are recovering native bee nests in sawmills that have been lost to forestry activities. The colonies are carefully placed in boxes for better conservation and rational use of their honey. Colombia Yucuna women from the Mirití-Paraná region of Colombia are working to document the origins of native bees in their culture and their importance to the territory and the environment. They are doing this hand in hand with the wise grandmothers and grandfathers of the villages. They collect stories, songs and drawings about bees. MExico About 20 years ago, Nahua families in Cuetzalan del Progreso, Mexico, began promoting meliponiculture as an ancestral practice that was being lost. Today, honey harvesting benefits the families economically and allows them to protect their territory. And in southeastern Mexico, the Colectivo de Comunidades Mayas de los Chenes has put native bees at the center of its fight against GMOs and agrotoxins. The women's voice and the protection of meliponiculture, a traditional practice and their livelihood, have been key to defending their territory. SOURCES -S. Engel, M. et al. “Stingless bee classification and biology (Hymenoptera, Apidae): a review, with an updated key to genera and subgenera”, ZooKeys. -Practical guide for the implementation of meliponiculture in the Colombian Amazon, Amazon Conservation Team/The Nature Conservancy, 2020. -Importance of meliponiculture", General Directorate of Natural Resources and Biosecurity. -"Native bees of Mexico. The importance of their conservation", Conacyt.

Read more

Leading participatory monitoring processes for Green Climate Fund financed projects

The Green Climate Fund (GCF), a multilateral climate fund under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), allocates funding for projects and programs aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and building resilience to climate change impacts in developing countries. To date, the GCF board has approved 243 projects worldwide, committing 13.5 billion USD in total. Notably, approximately 26% of these projects and programs target Latin America.This financial mechanism has become a lynchpin of the climate finance architecture, challenging conventional approaches to international projects. It is governed by a board with equal representation from developed and developing countries (UNFCCC designations); robust environmental and social policies rooted in human rights; an indigenous people’s policy, backed by an advisory group that interfaces with the Secretariat and the Board; a stated preference for maximal information disclosure; a seat for active observers representing civil society organizations; strong ties to the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement; and an explicit mandate to include a gender perspective. In fact, all approved projects and programs are required to integrate a Gender Action Plan (GAP). In addition, the GCF is mandated by its own policies to facilitate stakeholder participation mechanisms. These mechanisms encompass representation from diverse sectors, including the private sector, civil society organizations, vulnerable groups, women, and indigenous peoples.Though implementation of these safeguards and progressive policies is far from perfect, their existence lays the groundwork for stronger future implementation. Civil society, including feminist movements and organizations, engage with the GCF as a climate finance mechanism that should continue to be strengthened. The explicit analysis and commitment mandated for each project regarding social and gender considerations not only facilitate engagement but also uphold accountability.In late 2022, partner organizations of the Global Alliance for Green and Gender Action (GAGGA), including the International Analog Forestry Network (IAFN), Asociación Interamericana para la Defensa del Ambiente (Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense, AIDA), Fondo Centroamericano de Mujeres (Central American Women’s Fund, FCAM), Fondo Tierra Viva (Tierra Viva Fund) and Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO), collectively launched a pilot initiative. The project aimed to facilitate participatory monitoring of the implementation of the project FP089 Upscaling climate resilience measures in the dry corridor agroecosystems of El Salvador (RECLIMA). 3 RECLIMA was approved by the Board of Directors of the GCF during its 21st meeting (B.21) in 2018. For the fieldwork, an alliance was formed with Unidad Ecológica Salvadoreña (Salvadorean Ecological Unit, UNES), a local ecofeminist NGO advocating for environmental and gender justice in El Salvador.The main objective of this project was to pioneer a participatory monitoring process for a GCF-funded project, with specific emphasis on gender equality. Each participating organization approached this collaborative initiative with genuine curiosity, eager to explore its feasibility and potential impact. There was also a collective commitment to openly share information about the process, results, challenges, and lessons learned. This report aims to summarize the outcomes of this exercise, providing an overview of the RECLIMA project and highlighting the importance of gender equality and participatory monitoring within climate projects; as well as sharing primary findings and key recommendations, tailored to GCF Accredited and Executing Entities. Read and download the report

Read more

How the Inter-American Court can help protect human rights in the face of the climate emergency

The climate crisis has been identified as the most urgent problem facing humanity and the greatest threat to human rights. In this context, what obligations do States have to protect people, especially those in vulnerable situations, from its effects? The Advisory Opinions of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights provide a powerful answer to this question, since their purpose is to specify the content and scope of the obligations to protect human rights that the States of the Americas have under their domestic laws and the treaties or conventions they have signed. The international court is currently in the process of issuing an advisory opinion to clarify these obligations, specifically regarding the climate crisis. The interpretations provided by the Court in this case will strengthen the arguments of organizations, communities, and other actors who decide to initiate climate litigation before national or international tribunals. It’s important, then, to understand what these advisory opinions are, why they are important, and how they relate to climate litigation; as well as this opinion’s potential for moving the region toward climate justice. What are the Advisory Opinions of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights? The Advisory Opinions of the Inter-American Court are pronouncements issued by this international court—at the request of both the members of the Organization of American States (OAS) and of some of its affiliated organizations—in order to interpret international treaties such as the American Convention on Human Rights, to clarify their scope, to determine the specific obligations they impose, and to develop the guarantees they provide to the inhabitants of the continent. They are important because they consolidate the correct understanding of human rights and thus guide States on how to guarantee and apply them within their territory or jurisdiction. A clear example is Advisory Opinion 23 of 2017, in which the Court set a historic precedent by recognizing the right to a healthy environment as fundamental to human existence and for the first time pronouncing on the content of this right. These declarations contribute to a better understanding of the obligations, authorizations and prohibitions deriving from each of the rights recognized in the international treaties signed by the countries of the continent. They therefore constitute a relevant element in determining the responsibility of a State for possible human rights violations resulting from its actions or omissions. What is the process by which advisory opinions are issued? Any member of the OAS or any of its member institutions may request an advisory opinion to ask the Inter-American Court how to interpret its provisions or those of "other treaties for the protection of human rights" in the hemisphere. The questions must be specific and justified. Once the consultation is received, the Court informs all member states and the organs of the Inter-American Human Rights System so that they may submit their written comments. At the same time, a period of time shall be opened for any interested person or entity to submit to the Court its considerations on the issues raised and how they should be resolved. The Court will then, if it deems it necessary, convene oral hearings to hear the States and other actors involved in the process. It may also ask questions and seek clarification on the written submissions it has received. The Court will then deliberate the matter in closed session and adopt the relevant decision, which will be communicated by its secretariat to all parties to the proceedings. How do advisory opinions contribute to climate litigation? Climate litigation has emerged as an important and increasingly popular tool in the fight against the climate crisis. It is essentially strategic litigation that seeks broad societal change through judicial decisions that hold governments, corporations, and stakeholders accountable for the causes and impacts of the climate crisis. Advisory opinions of the Inter-American Court can help achieve these judgments by providing authoritative interpretations of human rights treaties adopted by states in the region. They serve as a legal benchmark for judging the actions or inactions of state entities and private actors under their control that have exacerbated or threaten to exacerbate the climate crisis. Treaties such as the American Convention on Human Rights establish guarantees for life with dignity, personal integrity and health, which can be invoked before courts as a basis for the obligations of States to adopt actions to adapt to and mitigate the climate crisis. Thus, the advisory opinions offer solid arguments to demand compliance with such actions as a way to protect human rights. Opportunities of the ongoing advisory opinion for climate justice In January 2023, Colombia and Chile requested an advisory opinion from the Inter-American Court to clarify the scope of States' human rights obligations in the context of the climate emergency. Both States stated that their populations and others in the continent are suffering the consequences of the global crisis, particularly due to droughts, floods, and fires, among others. Therefore, they consider it necessary for the Court to determine the appropriate way to interpret the American Convention and the rights recognized therein "in what is relevant to address the situations generated by the climate emergency, its causes and consequences." This will be the first time that the international court will rule on the mandates, prohibitions, and authorizations to be derived from human rights in the specific context of the negative impacts of the climate emergency on individuals and communities in the continent. Once issued, this advisory opinion will clarify the legal obligations of Latin American states to address the climate crisis as a human rights issue. The Court's opinion could compel governments to recognize their competence to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, support adaptation measures, and establish mechanisms to address loss and damage. Given this unique opportunity, AIDA is participating in the public consultation convened by the Court before it issues its Opinion. We have submitted a legal brief with arguments demonstrating the existence of an autonomous human right to a "stable and safe climate" as part of the universal right to a healthy environment, and the consequent obligations of states to prevent and avoid the harmful effects of the climate emergency on their inhabitants. In addition, we are supporting diverse communities in the region to bring their voices to the process and be heard by the Court by submitting other legal briefs that highlight the socio-environmental impacts of the climate emergency on indigenous peoples, women, children, populations with diverse gender orientations and identities, and fragile ecosystems such as coral reefs. We are also supporting the participation of community representatives in the hearings of the case, which the Court has scheduled for April and May in Barbados and Brazil, respectively. The climate justice movement in Latin America and around the world is growing stronger and more effective, fueled by successful climate litigation and important precedents such as the advisory opinions of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

Read more