Project

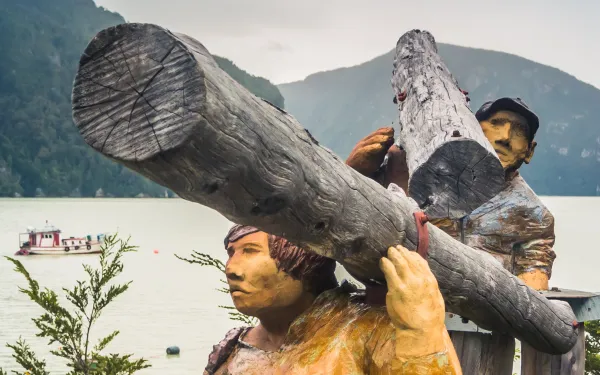

Photo: #RealChileProtecting Patagonian Seas from Salmon Farms

The Straight of Magellan in Chilean Patagonia (or Magallanes, as it’s known in Spanish) hosts the largest number of natural protected areas in the country. Permanent snow feeds the idyllic landscape, which has been shaped by glaciers, lakes, rivers and seas. Within its bounds live protected species—blue whales, sperm whales, Magellanic penguins, elephant seals, leatherback turtles, and southern and Chilean dolphins.

The cold waters of this far corner of the world are pristine; this makes them more sensitive to high-impact human activities. And now they’re being stressed by the arrival of salmon farms, which have already caused severe environmental damage in regions further north.

In Chile, the salmon industry uses harmful techniques and operates without proper regulation. Its rapid growth has overwhelmed coastal waters, filling them with huge amounts of antibiotics, chemicals, and salmon feces. These pollutants have led to partial or, in some places, complete lack of oxygen in the water, threating all forms of marine life.

Large salmon farms in the Magallanes region are already causing big damage. According to a government audit, more than half of the salmon farms operating there are affecting the availability of oxygen in the water, a condition that did not occur prior to their arrival.

Partners:

Related projects

Latest News

5 years of the Kawésqar National Reserve: pending issues for its protection

Local communities denounce that the area is highly affected by salmon farming, which is failing to comply with environmental regulations.On January 30, 2019, the Official Gazette published the decree creating the Kawésqar National Reserve in Magallanes, which extends over 2,842 hectares between fjords and Patagonian peninsulas. The purpose of this classification was to guarantee the protection of the area, its territory and biodiversity, as well as to establish that it is the duty of the State to ensure its conservation. This year, 2024, marks the fifth anniversary of this milestone, which begs the question: is the reserve's objective being achieved? The community's claimsWith the qualification of National Reserve, this area was separated from the Kawéskar National Park, which offers broader protection. In the opinion of the local communities, this administrative division determines in a whimsical way what to prioritize and separates the land from the sea, as if they were independent elements, which causes "divisions and confusion to grow at all levels," says Eric Huaiquil Caro, a member of the Kawésqar Communities Kawésqar Family Groups Nomads of the Sea. He also says that the "agreements that were made in the indigenous consultation have not been responded to." Finally, Caro asks that the conservation of this reserve be done "without salmon farms and we hope that this will be established in the Management Plan that will be submitted for consultation in March 2024." An overstressed areaWithin the Kawésqar National Reserve lie the richest kelp forests in the country, an ecosystem considered key to combating climate change, as they can absorb high levels of carbon dioxide and regenerate marine systems. Although the State must guarantee their protection, the area is experiencing great pressure from the salmon farming industry. For example, there are 133 approved concessions in the entire Magallanes Region and 85 in process, of which 68 approved and 57 in process are in the Kawésqar National Reserve, "which seems unusual to us because it has been proven that the salmon farming industry is neither sustainable nor compatible with the ecosystemic care of the reserve. This is fundamental to the creation of the Reserve's Management Plan, which is currently being designed and which should establish the incompatibility of the industry within the zone's protection mandate, as documented in the report we have prepared together with the communities," says Cristina Lux, an attorney with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA)."Forty-three percent of the concessions approved within the Kawésqar National Reserve have presented anaerobic conditions within the framework of their operations, according to information obtained from the Environmental Reports for Aquaculture. This means that they suffer or have suffered total or partial loss of oxygen, which affects the living conditions of all of the area's biodiversity," adds Estefanía González, Campaigns subdirector at Greenpeace Chile.The impact, explains Sofía Barrera , an attorney for FIMA, is "enormous and highly destructive.""To begin with, these farming centers are concentrated in just seven sectors (Staines Peninsula, Taraba Sound, Poca Esperanza Strait and Vlados Channel, Glacier Sound, Skyring Sound, Desolation Island and Xaltegua Gulf), which also concentrates their synergistic effects. Some of these are the impact of boat routes, the killing of sea lions to prevent them from attacking the salmon cages, the overproduction of salmon, the presence of garbage outside the concession polygons and the detection of the ISA virus in the farming centers, which ends up making the rest of the marine ecosystem sick, something that has been recognized by Environmental Courts," adds Barrera. "In addition, the dispersion of organic matter from the cultivation centers causes eutrophication and harmful algal bloom events (HAB), generating significant changes in water quality and affecting marine life," adds González.In the opinion of the representatives of these three organizations, despite the legal prohibitions and environmental requirements, the fact that many of these projects have been submitted and approved through environmental impact statements raises legal and political questions. "Why are the authorities not ensuring the real care of this area, whose interests are being taken care of, and how is the salmon industry influencing our authorities," asks Barrera.Unfortunately, González adds, when explanations have been requested, "we have not received answers or certainty. That is why it is urgent to advance towards a management plan that really protects this ecosystem and does not allow more centers that put biodiversity at risk." Press contactVíctor Quintanilla (AIDA), [email protected], +521 5570522107

Read more

In Chile, progress for indigenous participation in decisions affecting their territories

In January, Chile’s Supreme Court ruled that indigenous communities have the right to be informed of and participate in decisions affecting their territory and way of life. The high court ordered industrial salmon farmer Nova Austral to engage in public participation processes prior to authorizing the relocation of four farms into the Kawésqar National Reserve. The government's Environmental Evaluation Service had authorized the relocation of those farms without implementing mechanisms for consultation with the Kawésqar communities, and later rejecting their requests for public participation. It did so by arguing that the farms posed no harmful environmental impacts. The case at hand Since 2018, AIDA has been working in strategic alliance with Greenpeace Chile and FIMA to exclude industrial salmon farming from protected areas in the Magallanes Region, in the heart of Chilean Patagonia, and to defend the rights of the Kawésqar peoples, ancestral inhabitants of the area's canals and fjords. By approving the relocation, the environmental authority ignored the effects that salmon farms have had in the Los Lagos region, in the extreme north of Patagonia, demonstrating the serious risks posed by the industry's expansion into the extreme south of Patagonia, still a pristine natural area. These effects include biological contamination from the introduction of exotic species, the indiscriminate use of antibiotics, and frequent mass salmon escapes, as well as the accumulation of food and feces on the seabed, generating total or partial loss of oxygen and red tides. The environmental agency also overlooked the fact that salmon farming is incompatible with the protection objectives of the Kawésqar National Reserve, one of which is "to comply with the fundamental demands of the Kawésqar people." In fact, when the reserve was created in 2018, an indigenous consultation process chose to exclude industrial aquaculture, considering the fragility of the ecosystems of the area and the indigenous cultural legacy, closely linked to the sea. An appeal for improvement Faced with the government’s authorization of salmon farming in their territory, Kawésqar communities—with the support of the coalition formed by AIDA, Greenpeace Chile and FIMA—filed an appeal before the Supreme Court for the protection of constitutional guarantees. The judgment in favor of public participation was significant due to the fact that Chile has often been questioned for its low standard of compliance with ILO Convention 169, the most important international instrument for guaranteeing indigenous rights, including the right to prior consultation. One of the main criticisms is that the regulation for incorporating indigenous consultation into the environmental assessment encourages this not to take place. This is particularly relevant in projects evaluated by Environmental Impact Statements, for which a consultative mechanism of lesser incidence is applied and which is subject to a great deal of discretion on the part of the authority to be carried out. Moreover, in precisely those cases—including the relocation of salmon farms— public participation is not mandatory, as it is for projects evaluated by environmental impact studies. This further diminishes the possibility for communities to have their voices heard in this type of procedure. The future of participation in Chile The Supreme Court’s decision in this case is a contribution to the deepening of public participation as a tool to improve environmental decision-making. It highlights the voice of indigenous communities in matters affecting their ancestral territory. It also broadens the geographic scope of citizen participation by recognizing that these communities exercise a legitimate interest in environmental conservation, thus breaking with the idea that direct involvement depends only on their proximity to where people live. We hope that this is the first step to completely rejecting the installation of salmon farms in the Kawésqar National Reserve, in any protected area and, in general, in the seas of Chilean Patagonia.

Read more

Chile: Report Finds That Approval of Salmon Farms in Kawésqar National Reserve is Illegal

The document prepared by national and international organizations highlights the incompatibility between this type of industry and the purpose of protection of the area. Even without an established management plan, there are already 57 salmon farming concessions, 113 in process and 6 resolutions of environmental qualification have been approved after the creation of the Reserve. Local communities in the area of the Kawésqar National Reserve—including Kawésqar Atap, As Wal Lajep, Grupos Familiares Nómades del Mar, Residentes Río Primero and Inés Caro—provided Chile’s National Forestry Corporation (CONAF) with a technical report that seeks to provide information on the serious impact that the salmon industry generates on marine ecosystems. Prepared by the NGOs FIMA, Greenpeace and AIDA (the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense), the report will be considered in the management plan that the government entity must develop and implement to comply with the protection of the marine waters that make up the Reserve. "CONAF must guarantee compliance with what was established in the Indigenous Consultation and explicitly prohibit salmon farming in the reserve's management plan. This definition is key to the future health of the Patagonian marine ecosystems," explained Estefanía González, Greenpeace's Campaign Coordinator. "Salmon farming is completely incompatible with the maintenance of healthy marine ecosystems." Historic process for the protection of the Southern seas The creation of the Kawésqar National Reserve in 2018 was a key milestone for the participation of these native people in decision-making regarding the ecosystems that make up their ancestral territory. On that occasion, through indigenous consultation, the need to protect the waters and prevent the development of activities such as salmon farming was expressly established, considering the particular situation of fragility of the area and the Kawésqar cultural legacy, firmly linked to the sea. In their above referenced report, the organizations conclude that salmon farming as an activity is incompatible with the protection objectives of National Reserves, from a legal and ecosystemic point of view, and in particular with the Kawésqar National Reserve, due to the many risks involved. Among the damages caused by this industry are biological contamination caused by the introduction of exotic species, the indiscriminate use of antibiotics, periodic massive salmon escapes, and the food and feces deposited on the seafloor, which generate anaerobic conditions and red tides. All of the above endangers a marine area with unique diversity and which the State itself has decided to protect. "Allowing salmon farming in the Kawésqar National Reserve would render the protection given to the area useless," added Victoria Belemmi, FIMA attorney. "This point has even been recognized by the national directorate of CONAF, which when consulted in 2019 by the comptroller's office on salmon farming within protected areas, pointed out that according to the current national and international legal framework, including the Washington Convention, an activity such as salmon farming would not be admissible in an area designed to protect the marine ecosystem." Statement from the Comptroller's Office For its part, AIDA filed a letter with the Comptroller General's Office to solicit a ruling on the approval of a project to increase the biomass of a salmon farming center located in the Alacalufes Reserve, now Kawésqar National Reserve, which was operating under anaerobic conditions. "The approval of this project meant that salmon production was authorized to increase in an area where there was already evidence that the carrying capacity of the site was exceeded," explained Florencia Ortúzar, AIDA attorney. "The fact that the center was located in the waters bordering the Alacalufes Reserve (now Kawésqar) makes it even more serious." The low level of oxygen affecting the waters was evidenced by official documentation recognizing the regulations for that purpose—the Preliminary Site Characterization that the center's owner submitted to request the expansion, and several preliminary reports (INFA) confirming the situation. With the approval, the center acquired authorization to almost triple its original production. Subpesca had noted the situation, even interposing an observation on the matter within the process. However, shortly thereafter, it issued its approval of the project. Subsequently, the Environmental Evaluation Service (SEA) approved the project by means of an Environmental Qualification Resolution (RCA, for its Spanish initials). Read the report here (in Spanish) press contact Victor Quintanilla (Mexico), AIDA, [email protected], +5215570522107

Read more