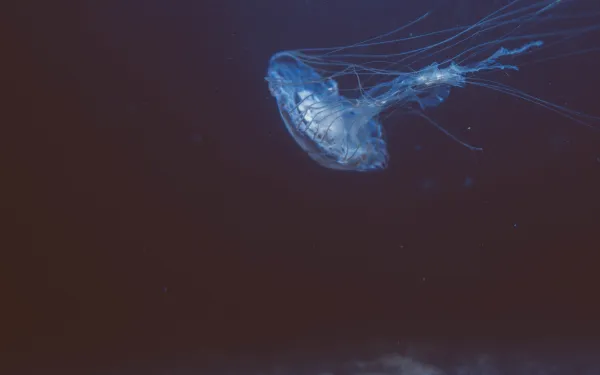

Ambition and urgency needed as high seas treaty negotiations near end

New York: With only one week to go in the negotiations for a new Treaty to protect two thirds of the ocean - the High Seas - civil society is raising alarm about the level of urgency and ambition towards a robust outcome for the ocean. A number of States have made public commitments to secure an ambitious Treaty at this final scheduled session, but there is concern that this is not being fully reflected in the formal negotiating room. The High Seas Alliance (HSA) expects more ambition to be shown by the United Kingdom, the European Union, Canada and the United States which have been public champions for the ocean, including at the recent UN Ocean Conference. These delegations support some progressive positions within the Treaty negotiations, but too many appear to be maintaining positions that will not result in the transformation we need for a healthy and productive ocean for current and future generations. Some states and groups are pushing for a strong outcome. CARICOM, (the Caribbean Community), the Pacific Small Islands Developing States, New Zealand, Costa Rica and Monaco are setting the pace for a speedy and effective outcome. This round of negotiations, known as IGC5, is the fifth and final scheduled meeting convened by the UN General Assembly. It is tasked with concluding a Treaty to protect Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, which includes the High Seas, and which makes up half the planet, two thirds of the ocean. For decades, the international community has struggled to reach this agreement during which time climate change and biodiversity loss have escalated. The HSA recognises that the “package” of elements under negotiation are intrinsically linked and critical to successful completion of the negotiations. “The greatest opportunity of our generation to show we are serious about protecting the global ocean is now. A strong High Seas Treaty is in reach but more ambition is needed. Governments must stick to their commitment to deliver a truly ambitious Treaty this week and finally move to taking action that will allow the ocean to recover and thrive; for marine biodiversity, Earth’s climate and the well-being of generations to come. There is no more time to waste. - Sofia Tsenikli, Senior Strategic Advisor to the HSA. QUOTES FROM MEMBER ORGANIZATIONS CANADA Susanna Fuller, VP Operations and Projects, Oceans North: "With the longest coastline in the world and as a self-declared ocean champion, Canada plays a vital role in achieving a strong Treaty. We are hoping to see Canada’s ambitions meet the urgent need for biodiversity protection and responsible management for 50% of the planet. With climate change impacts accelerating and biodiversity loss increasing, finalizing and implementing this Treaty cannot come fast enough." LATIN AMERICA Gladys Martínez de Lemos, Executive Director, AIDA (Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense): "Most Latin American countries have publicly stated their commitment to increase marine protected areas by 30% by 2030. This cannot be achieved without an ambitious High Seas Treaty. In addition, 70% of the areas that would not be protected need a high-level environmental impact assessment process with capacity and implementation. During all the negotiations Costa Rica has shown its commitment to a robust and ambitious Treaty. We thanked Costa Rica for its exemplary championship along these years." SOUTH KOREA Jihyun Lee, High Seas Alliance Youth Ambassador and undergraduate student at Yonsei University, South Korea: "Youth and future generations demand a strong and meaningful High Seas Treaty that will effectively protect the ocean. We are calling in unified support for world governments to finally take bold action for our ocean." US Lisa Speer, NRDC: “We applaud the more progressive approach of the United States, which has been a strong advocate for concluding the negotiations in a timely fashion, and for strengthening environmental assessment. However, we need the US to show more leadership to ensure that the new Treaty will result in the creation of a science-based network of fully protected areas in all areas of the High Seas, which scientists tell us is essential to reversing the decline of the ocean." EU + UK Laura Meller, Protect the Oceans campaign, Greenpeace: "It’s deeply concerning that the European Union and UK continue to insist on maintaining a broken status quo when it comes to creating ocean sanctuaries on the High Seas at this round of negotiations. The bloc and the UK must raise their ambition in the last days of negotiations if they truly want to be global ocean champions, and ensure that a strong Treaty which has the power to create properly protected ocean sanctuaries on the High Seas is finalised this week. If they don’t, their fine words in the run up to these negotiations will be little more than empty rhetoric. The oceans are in crisis. We need ambitious, urgent, action before it’s too late." PSID + CARICOM Travis Aten, Programme Officer, HSA: "We continue to applaud the Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS) and the Caribbean Community’s (CARICOM) continued leadership during this negotiation process, notably through their support of robust and ambitious conservation positions. As islands that are surrounded by the ocean, it is clear to them that this Treaty must move beyond the current status quo and implement real change on how we manage biodiversity of the High Seas." Fabienne McLellan, Managing Director, OceanCare: “It is encouraging to see that there is an increased spirit of urgency in the room. Many negotiators are rolling up their sleeves, aware that the world is watching to judge if the rhetoric on ocean commitments made in the lead up to this conference is translating into the Treaty text. While unfortunately some of the Treaty text elements are being watered down, it is not yet too late to make a turn around. Cementing the status-quo and the lowest common denominator is not good enough. We need an ambitious and implementable Treaty. The state of emergency of the ocean demands nothing less. NOTES Covering nearly half of the world’s surface, the High Seas—a true global commons—is only protected by a loose patchwork of poorly enforced rules that are ill-suited to address a growing onslaught of pressures to the water column and seabed below, including climate change, pollution, fishing, and emerging activities like deep-sea mining and bioprospecting. The negotiations began in 2018 and have since benefited from increased scientific and political awareness of High Seas marine life and habitats, as well as the dangers they face from human activities. For instance, until relatively recently, “High Seas” were considered to be largely devoid of life or too remote to face serious threats from overexploitation. Today, scientists have shown that they support marine systems that are vital to the global food supply, terrestrial ecology, and stability of the climate system. SPOKESPEOPLE Latin America Mariamalia Chavez (Spanish, English), [email protected] Gladys Martínez de Lemos (Spanish, English), AIDA, [email protected]

Read more