Blog

Spending climate dollars on large dams – a bad idea

During its last board meeting, the Green Climate Fund—charged with financing developing nations’ fight against climate change—approved two projects related to large dams. That means $136 million will finance large-scale hydropower, contradicting the Fund’s goal of stimulating a low-emission and climate-resilient future. We’ve said it before: large dams are not part of the paradigm shift we need. They worsen climate change and are highly vulnerable to its impacts. They also cause grave economic and socio-environmental problems that make it impossible to label them as sustainable development. dam Projects before the gcf While the two projects will exacerbate climate change, they aren’t the most destructive we’ve seen. The first is expected to generate 15 MW of electricity in the Solomon Islands, an impoverished Pacific archipelago highly vulnerable to climate change. Planned for the Tina River, the dam will be the country’s first major infrastructure project. Today, the Solomon Islands rely almost entirely on imported diesel to produce energy. It is an unreliable, highly polluting energy source for which residents must pay one of the highest rates in the region. We would have liked to see the Solomon Islands leapfrog toward a more sustainable alternative, avoiding the era of large dams altogether. But we were pleased to see the World Bank’s consultation and engagement processes with local communities, which lend legitimacy to the project. The second project will rehabilitate a dam built in the 1950’s in Tajikistan. The repairs will make the dam more resilient to weather and less subject to accidents. Since it is focused on rehabilitation, the project will not generate the socio-environmental impacts typical of ground-up dam construction. Tajikistan already gets 98 percent of its energy from hydropower, an increasingly unreliable energy source. In fact, during colder months, when more energy is needed, more than 70 percent of the population suffers cutbacks due to the malfunctioning of dams. It’s unreasonable to use climate finance to deepen a country’s energy dependency instead of diversifying its matrix and increasing its climate resiliency. Our Campaign against large dams When we learned that large dam proposals would come before the Fund, just before the 14th meeting of the Board of Directors, we drafted a letter explaining why large dams are ineligible for climate funding. Then, in anticipation of the 16th meeting, during which the projects would be discussed, we sent Board Members an informational letter on each of the projects, signed by our closest allies. Finally, during the board meeting, we circulated a statement signed by a coalition of 282 organizations, further strengthening our position against the funding of large dams. We obtained official replies from several members of the Board, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (in charge of the project in Tajikistan), and the Designated National Authority of the Solomon Islands. Delegates from Canada and France requested further discussion of the issue. The problems with large dams received international media attention through articles published in The Guardian and Climate Home. Advancing with Optimism Although financing was ultimately granted to both of the projects, we managed to draw international attention to the contradiction inherent in funding large dams with money designated to combat climate change. Several members of the Green Climate Fund expressed doubts about further promoting large hydropower initiatives. We’re confident they’ll raise their voices when faced with projects far more damaging than those recently approved. Cheaper, more effective, and more environmentally friendly alternatives need the support and momentum the Green Climate Fund can provide. Both solar and wind power, for example, have proved to be more efficient and less costly than large-scale hydropower. Other less-developed technologies, such as geothermal, have largely unexplored potential. As part of a coalition of civil society organizations monitoring the Fund’s decisions, AIDA will continue working to ensure that the recent decision to fund large dams does not become a precedent.

Read more

In search of legal protection for Mexico’s reefs

From the coasts of Baja California to the shallows of the Caribbean, Mexico is home to an incredible array of reefs. The coral and rocky reefs found throughout the country are sources of food and potentially life-saving genetic material. They protect people on the coasts from the impacts of storms and hurricanes, stimulate tourism, and provide shelter for a wide variety of plants and animals. Despite their inherent value, Mexico does not yet have an overarching law for reef protection. This vital task is instead governed by a variety of legislation and by international treaties that establish the country’s obligations to preserve these valuable ecosystems. Climate change is one of the most serious threats to reefs. Oceans are becoming warmer and more acidic, conditions that reduce reefs’ capacity to grow and repair themselves. In addition, warmer water disperses the algae that corals feed on, leaving the corals weakened and at risk of death. This month, the Mexican Senate’s Special Climate Change Commission decided to do something about the threats facing corals. They convened a series of meetings to promote the creation of a legislative instrument aimed exclusively at protecting the nation’s many reefs. I participated in these meetings as a representative of AIDA, alongside our colleagues from Wildcoast and scientists, academics, and community members who benefit from the services reefs provide. We drew the Senate’s attention to the serious threats facing reefs, and to the urgency of applying the precautionary principle to guarantee the human right to a healthy environment, which is at risk due to the lack of adequate regulations for reef conservation. To guarantee this right and to protect the oceans against climate change, Mexico has signed international treaties including the American Convention on Human Rights, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, and the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles. The Veracruz Reef, an emblematic case Reefs around the country are also being threatened by inadequately planned coastal infrastructure and insufficient environmental impact assessments. This is the case with the expansion of the port of Veracruz, a project that endangers the Veracruz Reef System, the largest coral ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico. The site was declared a Natural Protected Area in 1992, a priority region for the National Commission for the Knowledge and use of Biodiversity in 2000, a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 2006, and a Ramsar site. Even so, the government reduced the size of that area in 2013 to make way for the port project, violating international conventions such as the Ramsar Convention, under which the Veracruz reef is recognized as a Wetland of International Importance. Learn more about the case in the following video: Hope for Mexico's Marine Heritage We are confident that the Senate initiative will bear fruit and that Mexico will develop a law for the protection of its reefs, and that it will be born from a transparent and participatory process to which we will continue to contribute. To learn more about the topic, see our report The Protection of Coral Reefs in Mexico: Rescuing Marine Biodiversity and its Benefits for Humanity.

Read more

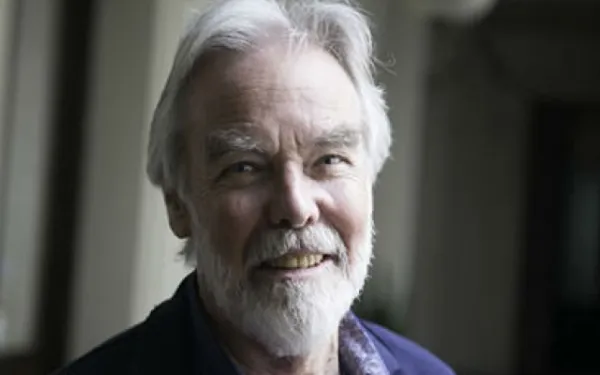

Remembering Robert Moran

It is with great sadness that we share news about the passing of Dr. Robert E. Moran, a distinguished hydrogeologist who was an immense resource in furthering environmental protection globally and a dedicated partner to AIDA. He died May 15 in a car accident while vacationing in Ireland. With over 45 years of experience in water quality monitoring, geochemical, and hydrological work, Dr. Moran was invaluable in the fight for clean water and responsible mining worldwide. His work as an expert on the environmental impacts of mining led him to collaborate with a wide range of actors, from non-governmental organizations and indigenous communities, to private sector and government clients. He was an admirable scientist and a strong defender of environmental rights. Some of Dr. Moran's recent projects in Latin America included: a review of technical issues at the Veladero gold mine in Argentina following a toxic cyanide spill; providing assistance and training to Colombian government officials on coal mine inspection and water quality monitoring; and preparing reports evaluating the environmental impact statements of the Minero Progreso Derivada II project in La Puya, Guatemala. Dr. Moran also conducted reviews of mining operations and their impacts in Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Honduras, as well as in Africa, Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and the United States. He dedicated his life to helping others understand and better evaluate the true costs of mining activities. Dr. Moran will be sorely missed by many in the environmental movement and people everywhere whom his life touched. We honor and thank him for all of his magnificent work to defend our planet.

Read more

Love for my daughter and the planet

Before I became a mother, I heard the question a thousand times: “Is it a good idea to bring more human beings into the world?” I often asked it myself. Thinking logically, the most obvious answer is no. The news shows us that we live on an overpopulated planet—one with water shortages, species extinction, alarming pollution and environmental degradation. It seems to be getting ever worse. That´s why, while being a mom is always difficult, being an environmentalist as well makes it even more so. Being an environmentalist is like fighting a million-headed monster: when one problem is solved, another 10 pop up. It means learning daily of the perilous situation facing our planet: the threats, the battles lost, the people and species suffering. Faced with such news, it’s impossible to turn a blind eye. Ignorance can no longer be an excuse for our actions. “What kind of world do you want to leave your children?” This is the question I’m faced with now. Yet it seems almost obsolete. It’s more important to think about what kind of world we want our kids to live in right now. To address this, parents like me are faced with an endless array of factors to consider before deciding something as simple as what to feed our children. It’s no longer enough that the food be balanced and nutritious. Now we must know if the food is pesticide-free, non-GMO, made with only natural ingredients… the list is endless. In Mexico, where I live, few children have the privilege of playing in a river or forest, on a beach or mountainside, or simply in the greenery of a park. In addition to keeping them safe from violence and human trafficking, we must also prevent our children from being exposed to high levels of air pollution. So if the world is so bad, why do we keep having children? They say that frogs do not breed unless they know there will be rain because, without rain, they know their offspring will be in danger. In the animal world, countless species regulate their reproduction based on their close relationship with nature. If conditions are not conducive, they do not reproduce. Are we human beings, then, the only species that reproduces at all costs, regardless of environmental threats? Humans are different from other species because of our awareness, and our ability to see beyond basic survival to things like art, love, empathy, and the search for meaning. Helping to make a difference is what brings meaning to my life. As part of the AIDA team, I work alongside professionals who dedicate their lives to saving rivers, defending human rights, protecting forests, supporting environmental defenders, empowering vulnerable communities, and giving a voice to the voiceless. It’s true that the news bombards us daily with worrisome stories about our planet. But it’s what the news rarely reports that shapes my vision of the future. Every day, I see a growing number of people who are prepared, engaged, and working to build a better world. They are mothers, fathers, children, students, teachers, professionals, and volunteers; they come from every imaginable country and culture; and they are willing to do whatever is necessary to help others. Above all, I see a critical mass of people that believe we can. We can change course, generate alternative energies, lessen our footprint; we can rectify wrongdoings, empower the vulnerable, combat xenophobia and greed; we can spend our money more wisely, and find more democratic ways of doing business. I have the privilege of working alongside a diverse group of people who have committed to fighting the good fight, and who won’t let go of the divine connection to the land that has given us life. These are the people who make me think that having children today is not only feasible, but also desirable. Because we can instill our children with generosity, compassion and respect—not just for themselves and the people around them, but also for the trees, the rivers, the animals, and all living things. Still, I often wonder whether we’ll ever get it right. I wonder if my five-year-old daughter will become an adult in a world where fresh water and clean air are seen as basic human rights; or if they will be commodities within reach of only the privileged few. Though I’ve never questioned whether or not my decision to have my daughter was the right one, I do still return to the question of whether or not the world needs more people. And then I look at my daughter’s shining eyes, at her gentle hands, at her dancing legs, at her infectious smile and her tireless curiosity. In her soft embrace, I feel her generosity, her compassion, and her boundless hope. Her laughter is so deep it could wake the flowers in spring; her spirit so generous it can shine love out on all living things; and her potential so huge she just may be the one to help push our planet towards a brighter future. There is no answer, then, but YES. For my daughter, and all children who carry within the potential for a better world, we will continue working to defend our beautiful planet. Join us! AIDA is an international nonprofit organization that uses the law to protect the environment, primarily in Latin America.

Read more

In times of climate change, we must respect nature

(Column originally published in El País) We are living now with the realities of climate change; to act otherwise would be ignorant and irresponsible. But, in case we forget, nature will surely remind us. Over the last months, severe landslides have devastated communities in Peru and Colombia. Together, they left more than 500 people dead, dozens missing, and more than 100,000 victims. Tragedies like these have some things in common: they occurred in cities and regions with high rates of deforestation and changes in land use; in both areas there was evidence of poor planning and regulation. Effectively, these disasters were foreshadowed. They make clear once again the vital need to care for our forests and riverbanks, and to avoid deforestation and erosion. Climate change means hard rains, fires, and hurricanes will become increasingly frequent and more intense. In Mocoa, Colombia, the equivalent of 10 days of rain fell in just one night, causing flash flooding that devastated much of the small town. In many cases, nature is only taken into account after tragedy strikes. But nature, when well cared for, can literally save lives. In Mocoa, a native forest helped protect one neighborhood from being washed away. That’s why environmental protection must be taken seriously, and any exploitation of natural resources must be well planned and sensible. Yet in Latin America, there remains a regional tendency towards unregulated extractivism. Over the last few years, governments across the region have been weakening environmental regulations in the name of development. Meanwhile, year after year, hundreds of people in Latin America and the Caribbean—especially children and others in vulnerable situations—die from events associated with droughts and floods. Activists, movements, mayors, and others seeking to protect land and water from extractive activities are frequently criticized, even criminalized and attacked. In the small Andean town of Cajamarca, Colombia, 98 percent of voters recently chose to ban all mining in their territory. It’s a decision that has sparked national controversy. Critics of the referendum have questioned whether the results are mandatory, despite the fact that Colombian law clearly states, “the decision of the people is mandatory.” Through their popular vote, the people of Cajamarca reminded their government of its commitment to protect their water and natural resources. Communities in Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Peru, and El Salvador have done the same. While some extraction is necessary in modern society, there must be a healthy balance. Not every project is safe, and alternative development models must be embraced and explored. It’s time to incorporate the environment into public policy and development, once and for all. Two Latin American nations have shown what is possible. In 2011, Costa Rica banned all open-pit metal mining. In March, El Salvador did the same. In both cases it’s a big yet viable change, because alternatives exist and it’s understood that protecting land and water is necessary to secure a healthy future. El Salvador has the second-highest rates of deforestation and environmental degradation, which has led to severe water scarcity. This is why the ban on metal mining passed there. It was no favor to environmentalists; it was based on years of sound analysis. Social and economic studies of the proposal concluded that the best thing for the country was to care for and restore its remaining forests and water sources. The decision prioritized environmental restoration—particularly its social and economic benefits—above the perceived benefits of mining. Environmental degradation is not a problem that exists in a vacuum. That’s why States have signed treaties and other international instruments that recognize their obligation to protect the environment. The Paris Agreement on Climate Change, signed by 34 of 35 States on the American continent, is the most recent. Now, more than ever, these commitments must be honored and fulfilled. Not all extractive projects are viable. Determining their worth must involve sound planning, coupled with policies and legal frameworks that are strong and effective. Environmental Impact Studies must be done carefully, objectively, and independently. Decisions should consider short- and long-term impacts on both local and national levels. We are living now with the realities of climate change; to act otherwise would be ignorant and irresponsible. But, in case we forget, nature will surely remind us.

Read more

Victory in Colombia: Citizens Vote to Ban Mining in their Territory

On March 26, 2017, 98% of voters in Cajamarca, Colombia decisively rejected mining in their territory. The results of the referendum (or “popular consultation”) are binding under Colombian law. Now municipal authorities must issue regulations to implement the ban. AIDA was part of the legal team that advised the Cajamarca community and developed a strategy, including the referendum, to stop a proposed mine that threatens to pollute the water supply. AngloGold Ashanti was in the exploration phase of a project called La Colosa (the Collosus)—aptly named, because it would be among the world’s 10 largest open-pit gold mines, the second-largest in Latin America. In a country coming out of a 50-year civil war, the referendum is a victory not only for the environment, but also for democracy. Banning mining through popular consultation demonstrates a commitment to solving environmental conflicts in a peaceful and participatory manner. It also allows citizens to exercise their human right to have a voice in public issues that affect them—a key element of true democracy—and to safeguard their human right to a healthy environment.

Read more

My time before the region's leading court on human rights

“Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness, that most frightens us.” - Marianne Williamson As I sat before the Court, one woman in a long line of observers, my pulse raced. For the first time in my life I was speechless, even awestruck. Towering regally over me sat six men and one woman, dressed in robes. The seven judges of the Inter-American Court on Human Rights. Public speaking is something I do regularly and with ease, but I was seriously nervous! My heart was going to explode; my throat was tight. I was acutely aware of the power of what I was about to say. I felt deep within myself the strength of my colleagues at AIDA. I sat up straight, took a deep breath, and leaned in closer to the microphone. As I began to speak, my words bore the influence of the last 20 years. I was representing AIDA in our very first intervention before the most important international human rights body in the Americas. We had been invited by the Court to comment on the consultative opinion raised by Colombian government on the link between environmental degradation and human rights; an issue reflecting the very core of our mission. The basic question to be addressed was this: If a megaproject damages the marine environment in the Greater Caribbean and, as a result, human rights are threaten or violated, should the State implementing the project be held accountable under international human rights law? When I began my career in environmental law 20 years ago, this very moment was one of my goals. I dreamt of engaging in this type of conversation before the Court; of influencing jurisprudence in the institution charged with protecting the human rights of the people of the Americas. Now, because I sit proudly as co-director of AIDA, those dreams have come true. Not just for myself, but also for all the brave and thoughtful attorneys I work alongside. The document we drafted represents countless hours of research and analysis, the contributions of human rights experts and environmental attorneys, decades of experience, lifetimes of dedication. We drafted it so the Court would recognize environmental protection as a human rights issue; that a healthy environment is essential to the enjoyment of all human rights. We hope it will show the judges of the Inter-American Human Rights System that incorporating international environmental law and standards can help them implement their mission. Remembering the months of work and the expert opinions in the document calmed me that day. The testimonies I heard were like music to my ears—more than 20 people, one after the other, from States and civil society organizations, spoke of the relationship between the environment and human rights; they spoke of the power of using international environmental law to protect people and communities. The arguments we crafted, together, made the link between the environment and human rights crystal clear. We had the historic opportunity to highlight how, in some situations, environmental degradation violates human rights. Protecting our environment, therefore, is an international obligation of all States in the Americas. When I finished speaking, I took a deep breath, and sat back in my chair. A smile broke across my face, as my phone began to light up with messages from my colleagues from every corner of the Americas. I left that day happily reflecting on the past 20 years, and wholly re-invigorated for 20 more. I left full of gratitude and pride for my team. And I left convinced of the power we have—as AIDA, as attorneys, as citizens, as human beings—to create change. It all goes to show that, while we may be small, we are not alone. Together we are powerful and, together, we are capable of building a better world. The decision is now in the hands of the Court, whose opinion has the power to influence the future of development in the Americas.

Read more

Costa Rica launches wetlands protection policy

On March 6, Costa Rica’s rivers, lakes, mangroves and other wetlands became better protected when the government launched its first national policy for their sustainable management. The National Wetlands Policy (2017-2030) was created to preserve and revitalize the nation’s wetlands and the great biodiversity they house. The Ministry of the Environment, the National System of Conservation Areas, and the United Nations Development Program created the historic public policy instrument over the last year and a half. AIDA helped develop the policy, providing comments based on international environmental law. We drew from our experience helping Mexico craft its own wetlands policy in 2014. “We sought to ensure that the National Wetlands Policy was in alignment with Costa Rica’s obligations under the Ramsar Convention, an intergovernmental treaty that states all countries should have a wetlands policy and provides governments with assistance protecting wetlands in their territory,” explained Gladys Martínez, senior attorney with AIDA’s Marine Biodiversity and Coastal Protection Program. Costa Rica’s Organic Law of the Environment defines wetlands as ecosystems that depend on both sweet and brackish water, are natural or artificial, and which can be permanent or temporary. Therefore, wetlands are not just bodies of water like rivers and lakes; they’re also marshes, mangroves, flood plains, and coral reefs, among others. “In Costa Rica we have thousands of wetlands that represent roughly seven percent of the national territory,” stated Edgar Gutiérrez, the Minister of Environment and Energy, in a statement released to mark the launch of the policy. “This policy will help improve the governance and protection of these resources, paying off a historic debt to our vital ecosystems.” Five main components The policy’s action plan is based on five strategic themes: Conservation of wetlands, their goods and services: Avoid future losses of wetlands and mitigate factors that endanger their health and wellbeing. It also proposes the creation of a National Inventory of Wetlands. Climate adaptation and rational use: Identify which wetlands are the most vulnerable to climate change and to carry out mitigation actions. Ecological rehabilitation: Once vulnerable wetlands are identified, recovery actions will be planned. Strengthening institutional support for adequate management: Better coordination and communication between the entities in charge of the management and conservation of wetlands. Inclusive participation: Citizens should be involved and participate actively in wetland-conservation processes. Community consultation It’s particularly important to celebrate the participatory nature of the policy. Many Costa Ricans base their lives and livelihoods on the health of wetlands and other natural environments. Now, instead of removing the public from decision-making, the government officially recognizes the importance of consultation. “The most important aspect of the policy is that, in addition to complying with the Ramsar Convention, the government is also complying with other international conventions that promote consultation,” Martínez explained. Costa Rica’s new policy represents a significant advance in defense of the environment. It shows the region that progressive environmental policies are possible. At AIDA we’re happy to say “Pura Vida!” to the wetlands. We hope more countries will join in their protection.

Read more

Changing the way we approach large dams

Cigarettes once served to cure cough; lead-based makeup was fashionable; and DDT, a highly toxic insecticide, was used in gardens where children played. At the time, little was known of their grave impacts on health and the environment. These facts may shock us now, but once they were normal. Cigarettes, lead, and DDT were widely believed to be more beneficial than harmful to humanity. Thanks to science, we learned of their serious health and environmental impacts. We’re learning the same now about large dams. A photograph of a dam surrounded by trees is as misleading as the doctor-approved cigarette ads once were. In the last decade, we’ve seen that the damage dams do to communities and ecosystems is far greater than the benefits they provide. Recently, an academic study confirmed something even more worrying: large dams aggravate climate change. At the end of 2016, researchers from Washington State University (WSU) concluded that reservoirs around the world, not just those in tropical areas, generate 1.3 percent of the total greenhouse gases produced by mankind. Dams, they found, are an “underestimated” source of contaminating emissions, particularly methane, a pollutant 34 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide. These findings have not yet been properly absorbed. Large dams continue to be funded and promoted as clean energy. Some countries boast nearly 100 percent renewable energy, yet reports show that at least half of that is hydroelectric energy, produced primarily by large dams. Violating human rights Even before WSU’s study was made public, the damage large dams do to communities and the environment was well documented. Dams disrupt traditional lifestyles, and affected communities are forced to adapt to new environmental conditions, such as altered river flow and species migration. Many communities have also been victims of forced displacement and fall into poverty as a result. In the Brazilian Amazon, the Belo Monte Dam provides a prime example of the ways dams cause negative impacts on both people and the environment. At AIDA, we’ve worked hand-in-hand with the indigenous and river communities of the Xingu River Basin, who have seen the trees fall around them, the red earth spread like a stain across their forest, the fish disappear from their rivers, and their small islands submerged. For those living in Altamira, the city nearest the dam, living conditions also worsened significantly, with increased violence, substance abuse, and prostitution. This story has been repeated thousands of times around the world. According to International Rivers, 57 thousand large dams had been built by 2015, disrupting more than half of the world’s rivers and causing the displacement of at least 40 million people. What can we do? Although the WSU study may surprise governments and corporations that promote the construction of large dams, for the health of the planet the trend must be stopped. Environmentally friendly alternatives exist, which do not imply the same social, economic and climatic impacts as dams. Hope can be found in the Brazilian Amazon with the Munduruku tribe. Last year, their long fight paid off with the cancellation of a large dam project on the Tapajós River, the sacred waterway on which their lifestyle depends. The decision to cancel the dam was backed with evidence of the impacts dams have on communities and ecosystems, exemplified by the case of Belo Monte. Recently, the Munduruku gathered to discuss and find solutions for the threats they continue to face as development rages in the Amazon. Solutions include the decentralization of energy sources, the promotion of small-scale projects, and solar and geothermal energy, all of which must be accompanied by adequate community-consultation processes. But they must be studied on a case-by-case basis and according to available resources, as what’s best for one community may not be best for another. Funding must carefully evaluate which projects to support, analyzing in detail the potential socio-environmental impacts. It may sound like people are making all the wrong decisions, but now is no time to be discouraged. We have the scientific information we need to care for our planet. Societal changes prove that we can change our actions to prioritize our health. Why can’t we do the same for the health of our planet? In the last several decades, the number of smokers has drastically decreased, we’ve stopped lacing makeup and other products with lead, and DDT has been regulated. In terms of large dams, the solution lies in re-thinking the way we produce energy and prioritizing the preservation of our free-flowing rivers.

Read more

Tárcoles: The most contaminated river in Central America

The sun rises slowly over the Rio Grande de Tárcoles. Guacamayas rest on treetops, and crocodiles laze upon the shore. Hundreds of tourists stop to photograph this beautiful moment when, suddenly, a hunk of garbage floats by. This is life on the Tárcoles, the most polluted river not just in Costa Rica but also in all of Central America. While the country has made great strides in moving beyond fossil fuels for power generation, there is still much to be done in terms of waste management. The source of pollution There are two main reasons for the excessive contamination of the large river: increasing urbanization and government bureaucracy. Within the river’s enormous span—which covers 4.2 percent of the Costa Rican territory—flows all the dirty water of the small nation’s Greater Metropolitan Area. In 2012, the State of the Nation report revealed that 96 percent of the country’s wastewater was untreated before entering the river. The Tárcoles suffers the consequences of this deficiency. The river is used as a city sewer, receiving the equivalent of 100 Olympic swimming pools of untreated water, according to the Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers. Its waters have been victim to antiquated laws that have for years favored economic activity above the river’s health. Despite an established fine for discharging wastewater and pollutants into the river, enforcement is not respected. As a result, the number of illegal spills of dirty water, tech waste, and garbage into the Tárcoles remains unchanged. Thanks to all of this, the National University’s environmental analysis laboratory estimated that if more effective measures were not adopted by the year 2040, the river’s recovery would be impossible. The river has been saturated with pollution, reaching the critical situation we find it in today. Environmental wealth at risk Despite the heavy pollution, the biological wealth at the mouth of the Tárcoles River is extraordinary. In its waters lives the largest American crocodile population in the country and around 50 species of birds. The river feeds the Guacalillo mangroves, home to a huge variety of animals, and four of the five species of mangrove in Costa Rica. This rich ecosystem also contributes to fishing and tourism for the subsistence of local communities, who pride themselves on its natural beauty. What’s been done and what’s left to do Efforts have been made to mitigate the impact of pollution on the river and to rescue its great biodiversity. The Los Tajos water treatment plant was designed to clean 20 percent of the waters that reach the Tárcoles. Isolated citizens’ cleaning campaigns have also made an impressive impact. In 2007, a cleanup of the river removed approximately 1,000 tires from its waters. This spurred the government to issue a decree favoring local communities, with the intention of guaranteeing their right to a healthy environment. The decree recognizes the biological importance of the river and the deterioration it has suffered. It created the Comprehensive Management Commission for the Rio Grande de Tárcoles Basin to plan sustainable ways to protect the river. These responses are steps in the right direction. However, more significant actions are needed to ensure the full recovery of the Tárcoles, before the damage becomes irreparable. The Commission has thus far been unable to mitigate pollution significantly. It needs better organization and more resources. The Commission should be involving local communities and carrying out massive cleanups in the river basin. The Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers must act efficiently to treat wastewater properly, prevent illegal spills, clean the river to restore the health of this sick giant, and control all water entering the river. The challenge is great, but the natural beauty of the river basin makes it a worthwhile effort.

Read more