Project

ShutterstockTowards an end to subsidies that promote overfishing

Overfishing is one of the main problems for the health of our ocean. And the provision of negative subsidies to the fishing sector is one of the fundamental causes of overfishing.

Fishing subsidies are financial contributions, direct or indirect, that public entities grant to the industry.

Depending on their impacts, they can be beneficial when they promote the growth of fish stocks through conservation and fishery resource management tools. And they are considered negative or detrimental when they promote overfishing with support for, for example, increasing the catch capacity of a fishing fleet.

It is estimated that every year, governments spend approximately 22 billion dollars in negative subsidies to compensate costs for fuel, fishing gear and vessel improvements, among others.

Recent data show that, as a result of this support, 63% of fish stocks worldwide must be rebuilt and 34% are fished at "biologically unsustainable" levels.

Although negotiations on fisheries subsidies, within the framework of the World Trade Organization, officially began in 2001, it was not until the 2017 WTO Ministerial Conference that countries committed to taking action to reach an agreement.

This finally happened in June 2022, when member countries of the World Trade Organization reached, after more than two decades, a binding agreement to curb some harmful fisheries subsidies. It represents a fundamental step toward achieving the effective management of our fisheries resources, as well as toward ensuring global food security and the livelihoods of coastal communities.

The agreement reached at the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference provides for the creation of a global framework to reduce subsidies for illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing; subsidies for fishing overexploited stocks; and subsidies for vessels fishing on the unregulated high seas. It also includes measures aimed at greater transparency and accountability in the way governments support their fisheries sector.

The countries agreed to continue negotiating rules to curb other harmful subsidies, such as those that promote fishing in other countries' waters, overfishing and the overcapacity of a fleet to catch more fish than is sustainable.

If we want to have abundant and healthy fishery resources, it is time to change the way we have conceived fishing until now. We must focus our efforts on creating models of fishery use that allow for long-term conservation.

Partners:

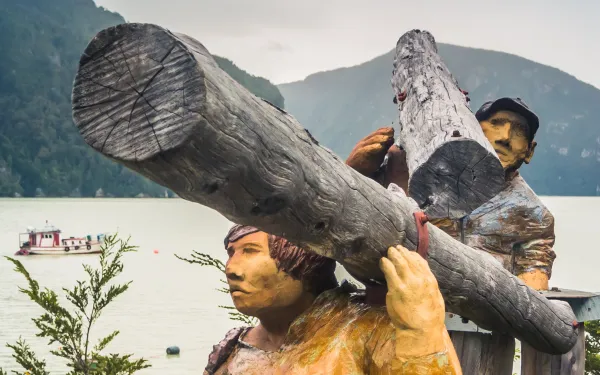

In Chile, progress for indigenous participation in decisions affecting their territories

In January, Chile’s Supreme Court ruled that indigenous communities have the right to be informed of and participate in decisions affecting their territory and way of life. The high court ordered industrial salmon farmer Nova Austral to engage in public participation processes prior to authorizing the relocation of four farms into the Kawésqar National Reserve. The government's Environmental Evaluation Service had authorized the relocation of those farms without implementing mechanisms for consultation with the Kawésqar communities, and later rejecting their requests for public participation. It did so by arguing that the farms posed no harmful environmental impacts. The case at hand Since 2018, AIDA has been working in strategic alliance with Greenpeace Chile and FIMA to exclude industrial salmon farming from protected areas in the Magallanes Region, in the heart of Chilean Patagonia, and to defend the rights of the Kawésqar peoples, ancestral inhabitants of the area's canals and fjords. By approving the relocation, the environmental authority ignored the effects that salmon farms have had in the Los Lagos region, in the extreme north of Patagonia, demonstrating the serious risks posed by the industry's expansion into the extreme south of Patagonia, still a pristine natural area. These effects include biological contamination from the introduction of exotic species, the indiscriminate use of antibiotics, and frequent mass salmon escapes, as well as the accumulation of food and feces on the seabed, generating total or partial loss of oxygen and red tides. The environmental agency also overlooked the fact that salmon farming is incompatible with the protection objectives of the Kawésqar National Reserve, one of which is "to comply with the fundamental demands of the Kawésqar people." In fact, when the reserve was created in 2018, an indigenous consultation process chose to exclude industrial aquaculture, considering the fragility of the ecosystems of the area and the indigenous cultural legacy, closely linked to the sea. An appeal for improvement Faced with the government’s authorization of salmon farming in their territory, Kawésqar communities—with the support of the coalition formed by AIDA, Greenpeace Chile and FIMA—filed an appeal before the Supreme Court for the protection of constitutional guarantees. The judgment in favor of public participation was significant due to the fact that Chile has often been questioned for its low standard of compliance with ILO Convention 169, the most important international instrument for guaranteeing indigenous rights, including the right to prior consultation. One of the main criticisms is that the regulation for incorporating indigenous consultation into the environmental assessment encourages this not to take place. This is particularly relevant in projects evaluated by Environmental Impact Statements, for which a consultative mechanism of lesser incidence is applied and which is subject to a great deal of discretion on the part of the authority to be carried out. Moreover, in precisely those cases—including the relocation of salmon farms— public participation is not mandatory, as it is for projects evaluated by environmental impact studies. This further diminishes the possibility for communities to have their voices heard in this type of procedure. The future of participation in Chile The Supreme Court’s decision in this case is a contribution to the deepening of public participation as a tool to improve environmental decision-making. It highlights the voice of indigenous communities in matters affecting their ancestral territory. It also broadens the geographic scope of citizen participation by recognizing that these communities exercise a legitimate interest in environmental conservation, thus breaking with the idea that direct involvement depends only on their proximity to where people live. We hope that this is the first step to completely rejecting the installation of salmon farms in the Kawésqar National Reserve, in any protected area and, in general, in the seas of Chilean Patagonia.

Read more

Peru’s Constitutional Court to hear case on Amazonian oil spills

The Court expects to resolve an amparo that communities of the Peruvian Amazon filed requesting the maintenance of the Norperuvian oil pipeline to prevent further spills. The lawsuit was supported with arguments on the international obligations of the Peruvian State to guarantee the rights to a dignified life and a healthy environment, among others. Lima, Peru. The Constitutional Court can stop the oil spills in the Peruvian Amazon and, with them, the systematic violation of the fundamental human rights of the indigenous peoples who live there. On Thursday, March 4, the Court is scheduled to hear and resolve an amparo filed by community members from Quebrada de Cuninico, Urarinas district of Loreto province, demanding the maintenance of the Norperuano oil pipeline, which would prevent new spills. In 2014, due to a leak in the pipeline, 2,500 barrels of oil were spilled into the creek, which negatively impacted the health and natural environment of the native communities of San Francisco, Nueva Esperanza, Cuninico and Santa Rosa. The unconstitutional amparo, filed in June 2018 with support from the Instituto de Defensa Legal (IDL), seeks a final judicial decision requiring the state-owned company Petroperu to oversee and monitor the operations of the Norperuvian Pipeline, the longest in the country, as well as to maintain all its pipelines in safe working order to prevent further spills. "It is urgent that the Peruvian authorities put an end to this structural problem that has affected the Peruvian Amazon for decades," said Juan Carlos Ruiz, IDL's lawyer. Recently, the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA) presented an amicus brief supporting the communities’ demand, using international human rights law to outline the State’s obligation to guarantee the adoption of administrative, legal, political and cultural measures necessary to protect the rights to a dignified life and a healthy environment. "The Amazon is an indispensable ecosystem for conserving the planet's climate," said Liliana Avila, coordinator of AIDA's Human Rights and Environment Program. "In contexts of climate crisis, the protection of this ecosystem and the indigenous peoples who inhabit it is an urgent and vital mandate." The brief also highlights the toxicity of oil to the environment and the duties of the Peruvian State and Petroperu to guarantee the health and integrity of those most vulnerable to hazardous substances, such as children, women and traditional communities. "There is evidence that the oil spills in the Peruvian Amazon, which directly affect indigenous peoples, are mostly caused by the corrosion of pipelines," says Connie Espinoza, Regional Technical Coordinator of the All Eyes on the Amazon Program (TOA). "The volume spilled is so large that se are finding it impossible to attend to all the remediation needs derived from each and every spill." According to The Shadow of Oil, an OXFAM report, pipeline corrosion and operational failures caused 65 percent of the 474 spills that occurred in Amazonian oil lots and in the Norperuvian Pipeline between 2000 and 2019—which affected the territory of 41 indigenous peoples—, while third parties caused just 28 percent. Pipeline operators are responsible for the vast majority of spills. The document also shows that, of the 2,000 sites impacted and contaminated by oil activity in Block 192, only 32 were prioritized for remediation, and that the volume of contamination, on average, would fill 231 national soccer stadiums. The lack of maintenance of the Norperuvian oil pipeline gravely impacts the Peruvian Amazon and violates the fundamental rights of native communities to enjoy a balanced environment, health, physical integrity, natural resources, territory and other rights of constitutional importance. press contacts: Gerardo Saravia, IDL, +51 997 574 695, [email protected] Nora Sánchez, HIVOS, +593 99 821 5617, [email protected] Victor Quintanilla, AIDA, +521 5570522107, [email protected]

Read more

Reaffirming the legitimate protection of the right to a healthy environment

In December 2016, two women from Veracruz decided to defend the Veracruz Reef System in court. They sought to protect the largest coral ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico from the expansion of the port of Veracruz, which would cause serious and irreversible impacts on the reef’s biodiversity and, by extension, the local population. Residents of the Veracruz metropolitan area, represented by the Centro Mexicano de Derecho Ambiental (CEMDA), filed an injunction against the project because its environmental permit resulted from a fragmented impact assessment that did not consider the full range of risks to the reefs. AIDA supported our partners at CEMDA by filing an amicus brief with detailed information on the important services the reefs provide: sequestering carbon, generating oxygen, producing food, and protecting coastal areas from storms and hurricanes, among others. In April 2017, the court that heard the case rejected the injunction and, with it, the request to suspend work on the port expansion. The court argued that the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate that the project had "a real and relevant impact" on their rights and that they lacked a "legitimate interest" in the case. Legitimate interest—also known as legal standing—refers to a person’s capacity to claim damages before a court of law, in any scope. In a traffic accident, for example, only you have the legitimate interest to claim the damages your vehicle may have suffered, which must be individual and quantifiable. However, in matters of environmental damage, the situation is more complex. The degradation of an ecosystem affects more than one person and even transcends generations. The residents of Veracruz appealed the judicial setback and their case arrived before Mexico’s highest court, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation. Given the lower court’s limitations in recognizing in its ruling the right of all people to equal access to justice in environmental matters, AIDA and Earthjustice filed a second legal brief before the Supreme Court, requesting an expansion of the requirements for legitimate interest. We provided legal and technical evidence regarding the human right to a healthy environment and access to justice, enshrined in international law. These rights mean that the Mexican government must ensure that anyone whose fundamental rights are threatened by environmental degradation has the possibility of achieving justice, regardless of whether their connection to the threatened ecosystem is indirect or remote. The Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide also contributed a brief that analyzes court decisions from various jurisdictions recognizing the right of any person, civil society organization, or local resident to file lawsuits against projects and decisions that may negatively affect the environment. Finally, on February 9, 2022, more than five years after the original lawsuit was filed, the residents of Veracruz won an important victory for the area’s reefs. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court found that government authorities violated the right to a healthy environment of the people of Veracruz by authorizing the port’s expansion. Since it was unopposed, the ruling creates a binding precedent for all courts of the nation. The Veracruz decision is a landmark ruling, valuable for not just Mexico but for the entire region because it: Ratifies that proximity to a project does not define who the affected people are or who can claim protection of their right to a healthy environment before the courts. Reaffirms that it is not necessary to prove quantifiable and individualized damage in order to have access to environmental justice; it is sufficient to demonstrate that a project or activity, by degrading an ecosystem, damages or threatens to cause damage (economic, social, cultural, health, etc.) to a community. Recognizes an expanded legitimate interest, as well as the collective nature of the right to a healthy environment and public participation in environmental assessment processes. Sets a precedent with the capacity to transform the way in which environmental impact assessments are carried out in Mexico, incorporating the principles of prevention and precaution. Points to Mexico's international obligations, including those acquired under the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean (Escazú Agreement). As an organization and individuals, we are celebrating this important step toward strengthening the defense of the right to a healthy environment in the region. We are proud to have contributed to this achievement, and hopeful that the implementation of the ruling will be carried out according to the highest standards.

Read more